Americans Divide Over Independence

According to the Merriam-Webster dictionary, a civil war is a war between opposing groups of citizens of the same state or country. By this definition or any objective measure, our nation experienced a civil war from about 1773 to 1783. It was much worse in its intensity and cost than anything from the Civil War, including Sherman’s infamous March to the Sea.

In some ways, the American Revolution was the most bitter event in our nation’s history. While the Civil War, fought over four years, split the nation in two, it was largely a conflict between two regions of the country, the slave holding south and the free states of the north. In contrast, our Revolution, fought over seven years, was a more personal civil war, fought locally, often with neighbors fighting neighbors in many parts of the country.

The path to this first civil conflict began at the conclusion of the French and Indian War. Prior to this time, England had largely ignored her American colonies and let them govern themselves. After that war, the British became more assertive in North America, to include placing direct taxes on their American subjects for the first time.

England’s treasury was empty due to the cost of the conflict and English officials hoped to refill it on the backs of their American colonies. Consequently, Parliament passed the Stamp Act in 1765 to raise revenues. Not surprisingly, this new tax, like any tax, met with resistance.

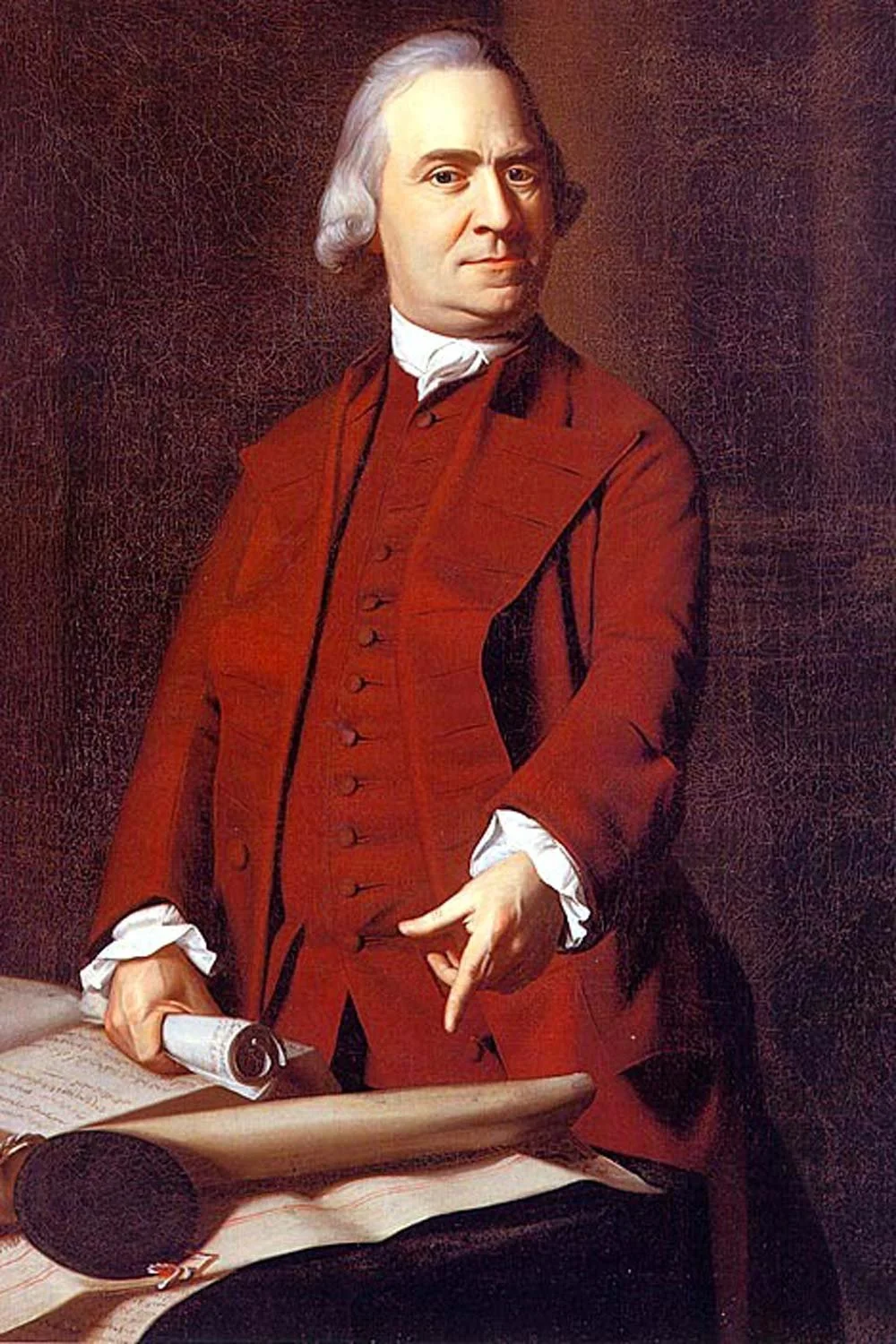

In Boston, Samuel Adams organized the Sons of Liberty, a sort of vigilante group, to help push back against this measure, and sister groups were formed in other colonies. They intimidated governmental officials into not collecting the tax and even instituted a practice known as “tar and feathering” (pouring tar on someone’s body and rolling them in feathers) to get their message across. While their violent methods were condemned by other patriots like John Adams, their actions helped lead to the repeal of the Stamp Act.

In 1773, Parliament tried once again to impose taxes on the colonists when it passed the Tea Act. This second attempt to raise revenues from the American colonies now faced opposition from people who were experienced in resisting British polices. Additionally, because of their previous success, they were more comfortable using violence to achieve their goals and, as to be expected, these methods grew more violent.

In this case, the seminal event was the Boston Tea Party on December 16, 1773, in which the Sons of Liberty threw 92,000 pounds of privately owned tea into Boston Harbor. Although Parliament soon closed the port of Boston, this action mattered little to the men who tossed the tea since none of them were merchants or ship owners.

By the middle of 1774, firebrands like Sam Adams were calling for a complete separation from England, and those that differed with this opinion were viewed as traitors to the cause. The Sons of Liberty now began to practice their intimidation tactics on their neighbors and friends who opposed independence. While mostly non-violent, they stifled dissent and suppressed opposing points of view.

John Singleton Copley. “Samuel Adams.” Boston Museum of Fine Arts.

Boston became the hotbed of insurrection and where the bitterness towards former friends first came to the surface. In general, those opposed to separation from England were the prominent and wealthy men of Boston, the lawyers, doctors, and merchants, men like Bostonian Thomas Hutchison, the Royal Lieutenant Governor.

While not universally the case, proponents of revolution tended to come from the poorer and less successful classes, men like Sam Adams, an unsuccessful tax collector who struggled financially. This same tendency would be repeated as the revolutionary movement spread to other areas of the country. It seemed that those that did well in the English system wanted to keep it, while those that did not prosper blamed the system itself for their ills.

Emotions finally erupted on April 19, 1775, with the Battles of Lexington and Concord, marking the start of our American Revolution. Now the simmering animosity between patriots and loyalists would come to a boil and be practiced out in the open. Soon, killing neighbors, destroying houses and farms, and ruining lives would become all too common place in America.

It could be argued that without the intimidating and violent tactics of the Sons of Liberty, America would never have gained her independence. Perhaps so, but it is hard to say. In any event, the genie was now out of the bottle and the bloodshed was just beginning.

Next week, we will talk more about how neighbor fought neighbor in the American Revolution. Until then, may your motto be “Ducit Amor Patriae”, Love of country leads me.

General George Washington led his Continental Army and the French Army under General Jean-Baptiste de Rochambeau into Virginia in mid-September 1781. The combined force was on its way to Yorktown and its appointment with destiny with the entrapped British command of General Lord Charles Cornwallis.