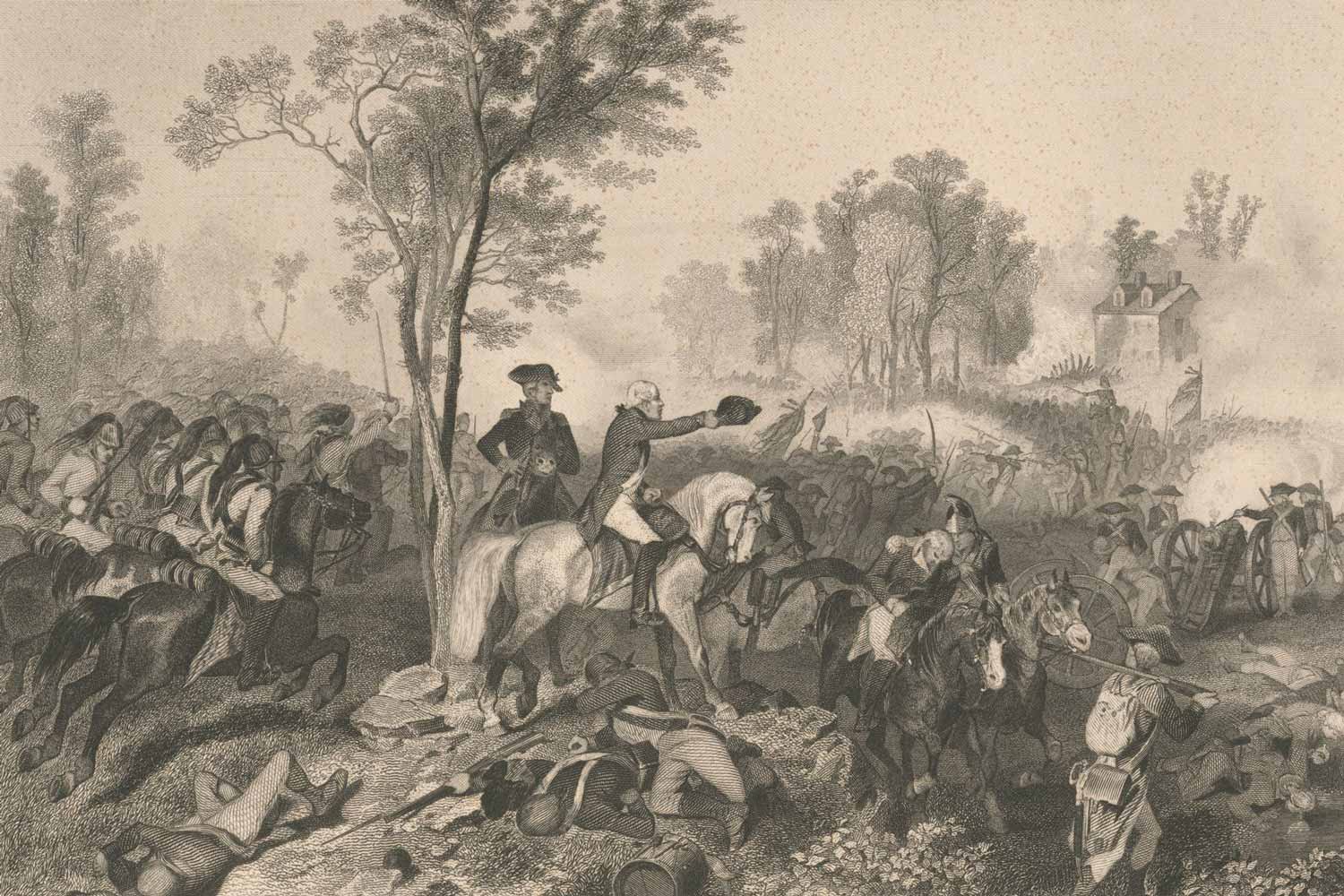

Closing Scenes in the Southern Theater of the Revolutionary War

By the late summer of 1781, the American Revolution in the South was drawing to a close. Hoping to inflict more damage to the British, Major General Nathanael Greene, the commander of the southern Continental Army, planned a strike at the one remaining British army in South Carolina.

The Redcoats had recently undergone a change of command when the very capable Lord Francis Rawdon had returned to England due an ongoing illness. Interestingly, Rawdon’s ship was captured by the French fleet heading to Yorktown, and he was an eyewitness to the French victory at the Battle of the Capes that sealed the fate of Lord Charles Cornwallis. He was replaced by Colonel Alexander Stewart, another talented veteran British officer, who would rise to be a Major General in the years following the American Revolution.

Greene and Stewart squared off at the Battle of Eutaw Springs, sixty miles from Charleston, on September 8, 1781, in what would prove to be the final major southern engagement during the American Revolution. While the Americans had 2,200 men, the Brits had only 1,600 troops available for the fight. That morning, due to a lack of bread, Stewart had detailed 400 men to forage the countryside for yams, not realizing Greene was coming his way. These men were surprised and easily captured by the Americans.

The fight began a little after 8:00am and see-sawed back and forth with neither side willing to yield. Greene, a veteran on many engagements, described the battle in a letter to General George Washington as “by far the most obstinate fight I ever saw.” The casualty lists prove him out as the Americans lost 557 men, one quarter of their army, while Stewart lost over 800 men (including the foragers), forty percent of his total force.

Ultimately, Greene was once again forced to retreat from the field of battle, giving the Brits a technical victory. As was too often the case for Greene’s liking, the Americans had been close to victory when it was snatched away from them. In this instance, after the British had started to flee, part of Greene’s army left the line of battle to pillage the abandoned British campsite. This diversion broke up the American attack and the English recovered and carried the day. But they soon retreated to Charleston, once again leaving their wounded behind in Greene’s care.

The disintegration of order among the Americans was largely due to a lack of officers. The Loyalists had learned from the Patriots the effectiveness of targeting officers to reduce the cohesion and control of the rank and file during a battle. At Eutaw Springs, sixty of the one hundred American officers were casualties, including four of Greene’s six generals.

Naturally, Greene was disappointed in yet another “oh-so-close-to-victory” defeat, but others recognized his incredible accomplishments. North Carolina Governor Abner Nash wrote to Greene that he possessed “the peculiar art of making your enemies run away from their victories, leaving you master of their wounded and of all the fertile part of the country.” Even the ever-complaining Congress awarded Greene a gold medal, one of only seven bestowed during the American Revolution.

Six weeks later, on October 19, Lord Charles Cornwallis surrendered to General Washington at Yorktown. In hindsight, this event effectively ended the war but that was not the general feeling at that time. In the minds of contemporary Americans, the threat of British power was still very real. The Brits still had strong garrisons in Savannah, Charleston, and Wilmington in the south with the largest force still occupying New York, representing a total North American troop strength of 47,000 men.

Despite the lack of set-piece battles, Greene had a formidable job for much of the next two years. For one thing, the supply situation, always deplorable, worsened as time went on and Continental currency depreciated to the point of being almost worthless. With victory in sight, many in Congress chose to ignore the needs of the army. In a letter to Superintendent of Finance Robert Morris, Greene wrote that for two months one third of his men had nothing to wear but breechcloths and the remainder were “ragged as wolves.”

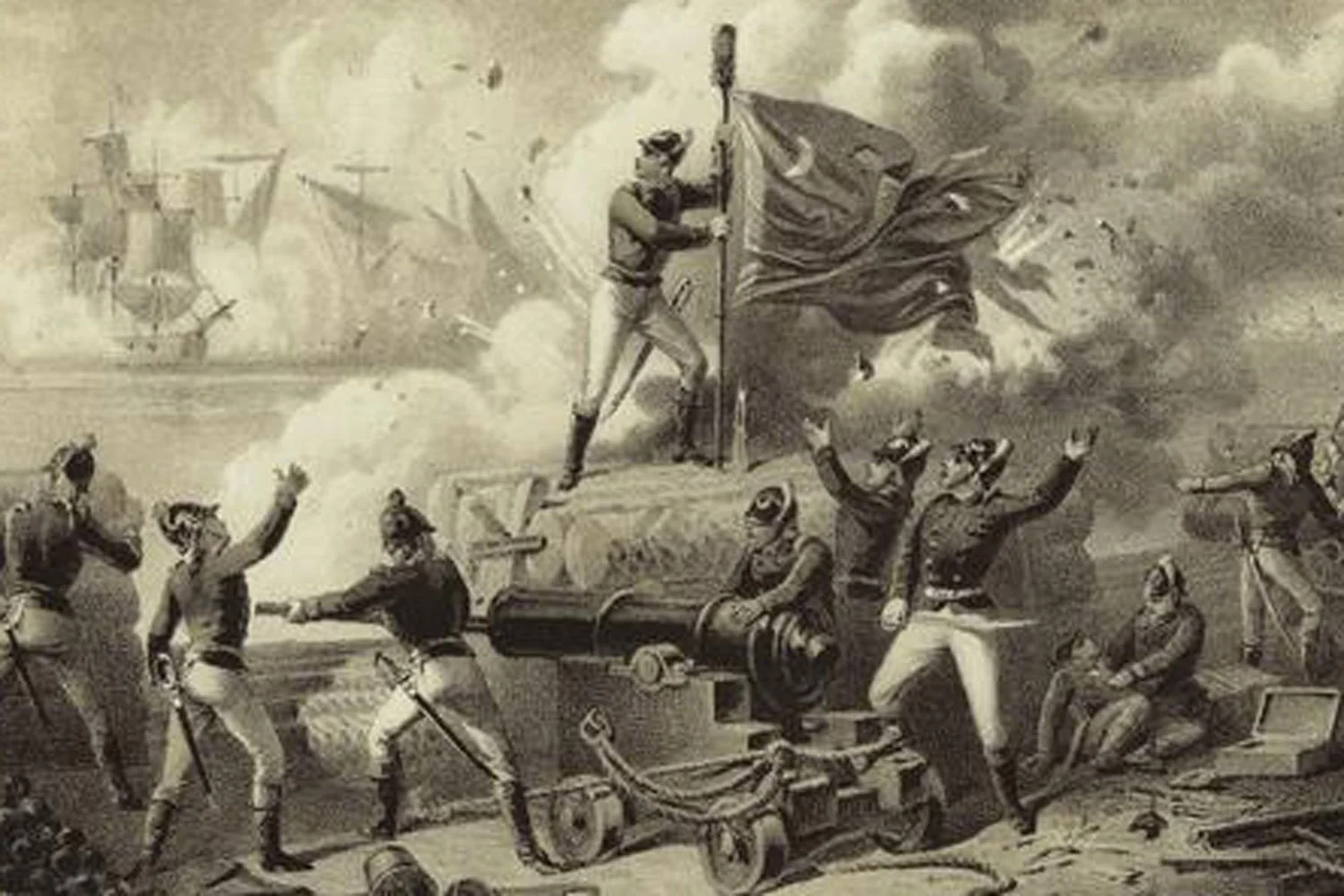

Heppenheimer & Maurer. “Fort Moultrie on Sullivans Island near Charleston, June 28, 1776.” New York Public Library.

There was also the continuing civil conflict between Loyalists and Patriots, with the deep mutual hatred leading to atrocities on both sides. Greene worked hard to discourage retribution against Loyalists, writing to a subordinate, “If we pursue the Tories indiscriminately and drive them to a state of desperation, we shall make them…a sure and determined enemy.” Unfortunately, much of his advice fell on deaf ears.

With peace negotiations underway in 1782, the British began to abandon their remaining posts in the south, leaving Wilmington in January, Savannah in July, and, on December 14, 1782, the last British troops in the southern states set sail from Charleston Harbor in 300 ships. That same afternoon, General Nathanael Greene led the Continental Army in a triumphant procession back into the city.

Next week, we will discuss the final days of Nathanael Greene and closing thoughts on the southern campaign in the American Revolution. Until then, may your motto be “Ducit Amor Patriae,” love of country leads me.

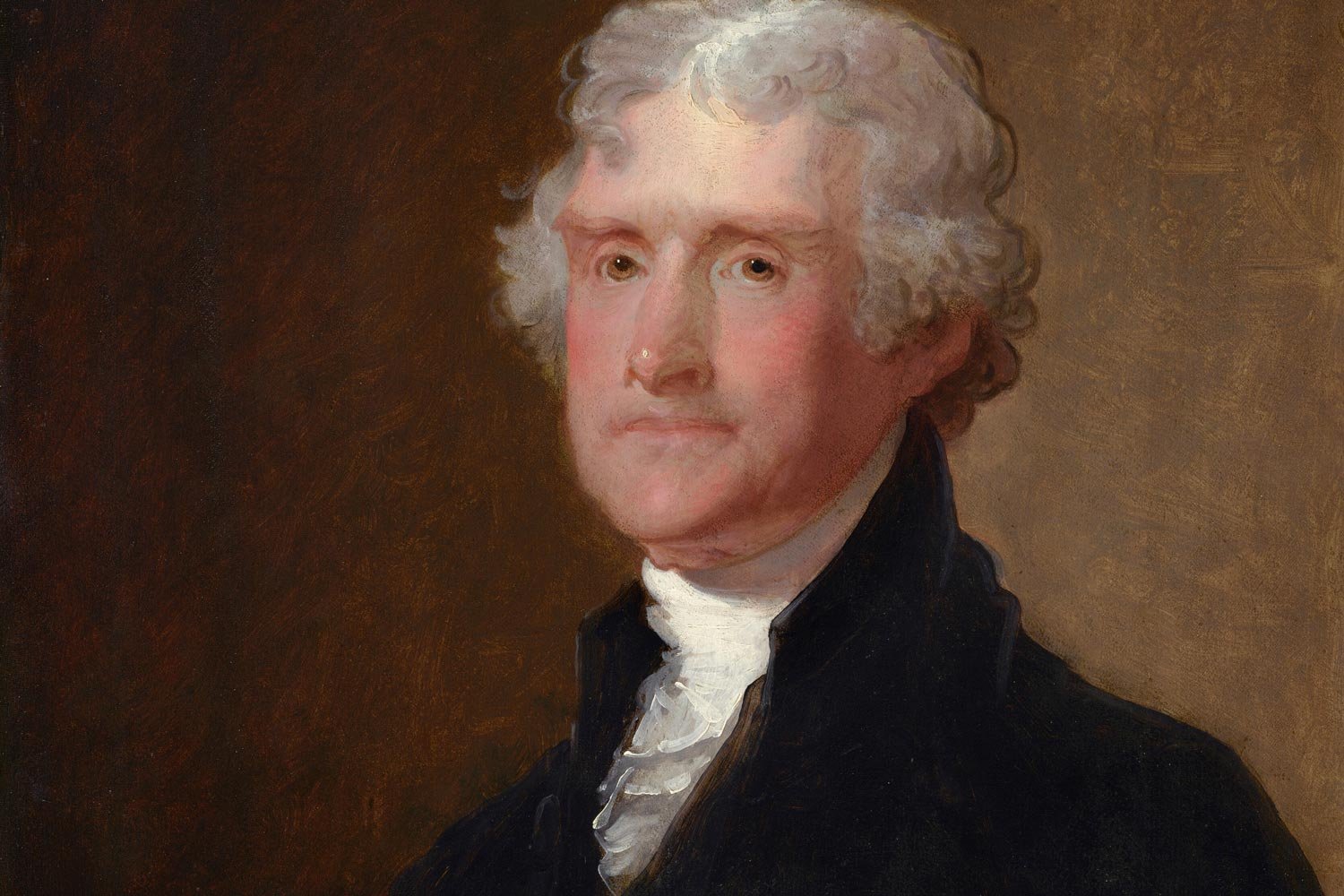

Thomas Jefferson’s revolutionary journey began in the 1760s and culminated in his masterfully written Declaration of Independence in 1776. But in between these events, Jefferson crafted one of the most impactful statements ever for American independence. Entitled A Summary View of the Rights of British America, it was perhaps the most logical assessment of the true relationship between Great Britain and her American colonies. The concepts Jefferson laid out had been refined and brought into focus following several dustups with Lord Dunmore, the new Royal Governor.