Arnold’s Scheme Goes Awry

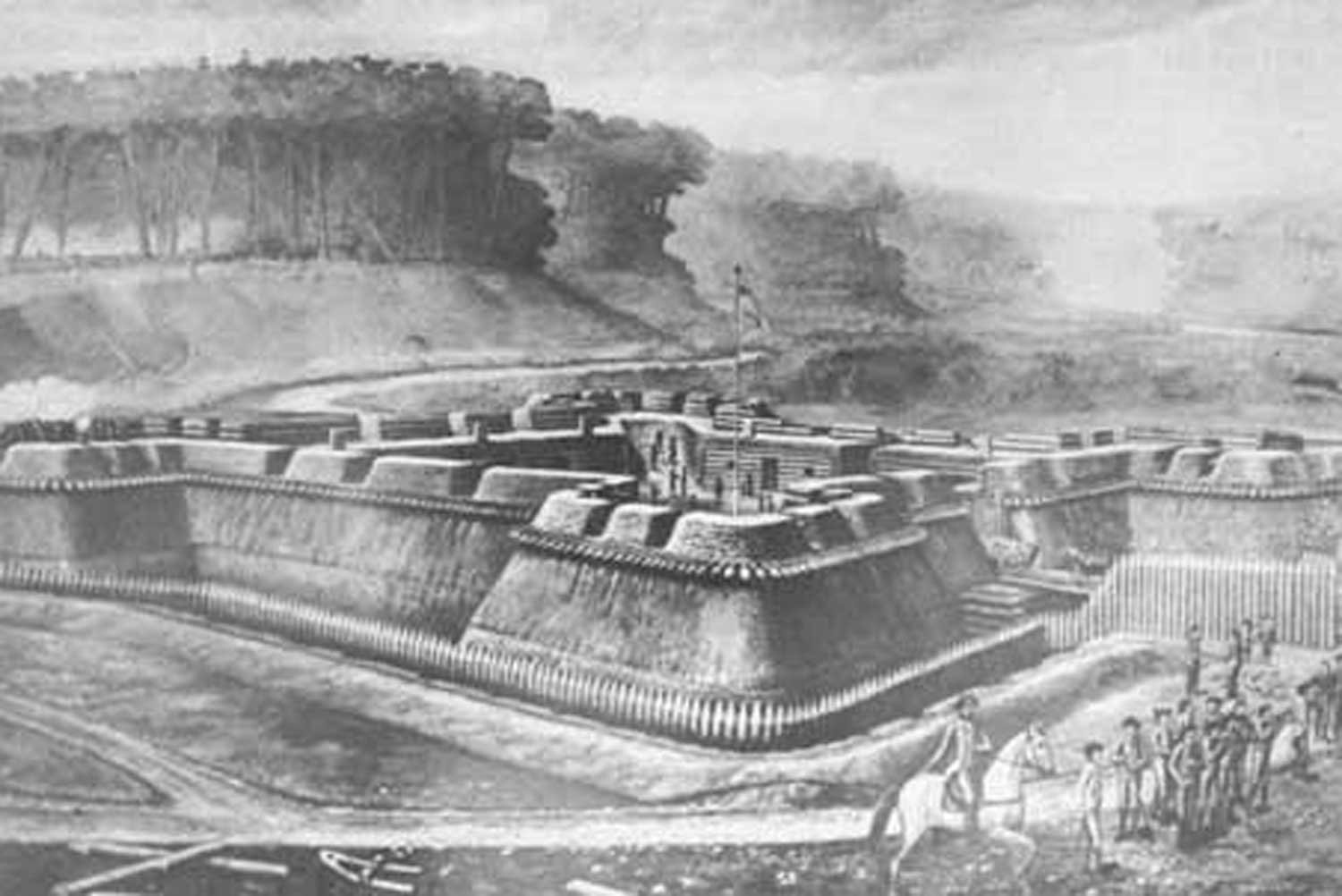

In June 1780, General George Washington gave the command of West Point to Benedict Arnold. Arnold swiftly took steps to weaken the fort’s defenses and arranged to meet with Major John Andre, the British spy chief, to turn over documents on the fortress. Arnold and Andre conferred until the early morning hours, but when ordered to take Andre back to his waiting ship, two local farmers hired by Arnold refused to go until they got some sleep. That would prove to be a fateful decision because while they slept, an American shore battery fired on and drove off Andre’s waiting vessel, leaving him no alternative but to make his way back to British lines on horseback.

Tom Hand, creator and publisher of Americana Corner, explores how Benedict Arnold’s scheme to surrender West Point failed, and why it still matters today.

Images courtesy of Yale University Art Gallery, Library of Congress, The New York Public Library, National Army Museum, Royal Museums Greenwich, The Metropolitan Museum of Art, Wikipedia.

In June 1780, Benedict and Peggy Arnold asked two old acquaintances who were congressmen from New York, Robert Livingston and Phillip Schuyler, to request that General George Washington give Arnold the command of Fortress West Point. Unaware of Arnold’s true motives and wanting to help their friend, both congressmen complied. Arnold was now certain West Point would soon be his to give away.

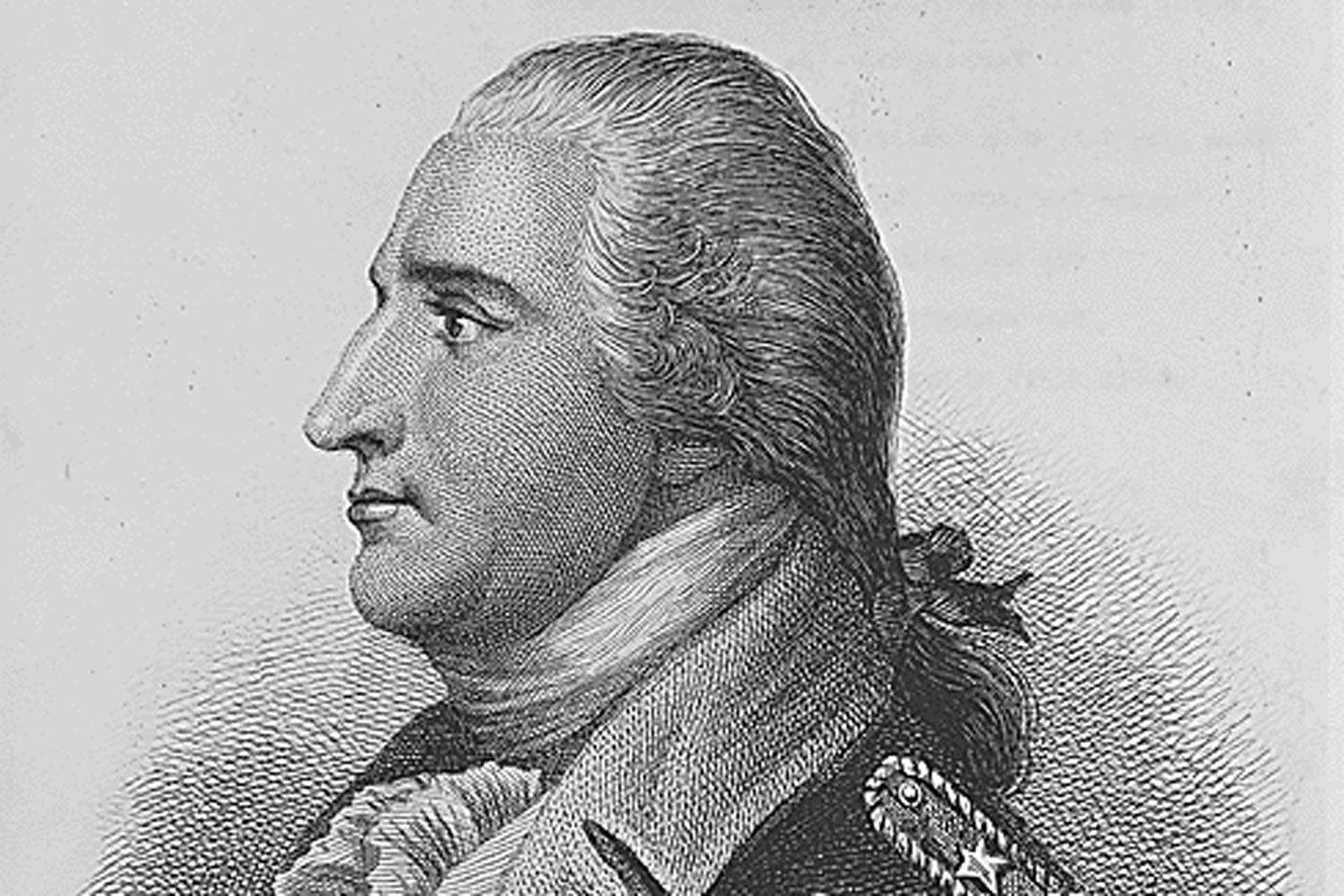

Benedict Arnold’s betrayal of the United States followed a series of disappointments and slights, both real and imagined. The final chapter in this sad story was the offer to hand over Fortress West Point to the British in September 1780, but the saga began in the Spring of 1779.

The Benedict Arnold who was named military commander of the Philadelphia region in 1778 was not the same man whose battlefield exploits had made him an early American legend. When Arnold had led his contingent of New Haven militiamen to the siege of Boston in April 1775, he was a wealthy, incredibly athletic man intent on helping the United States gain its independence.

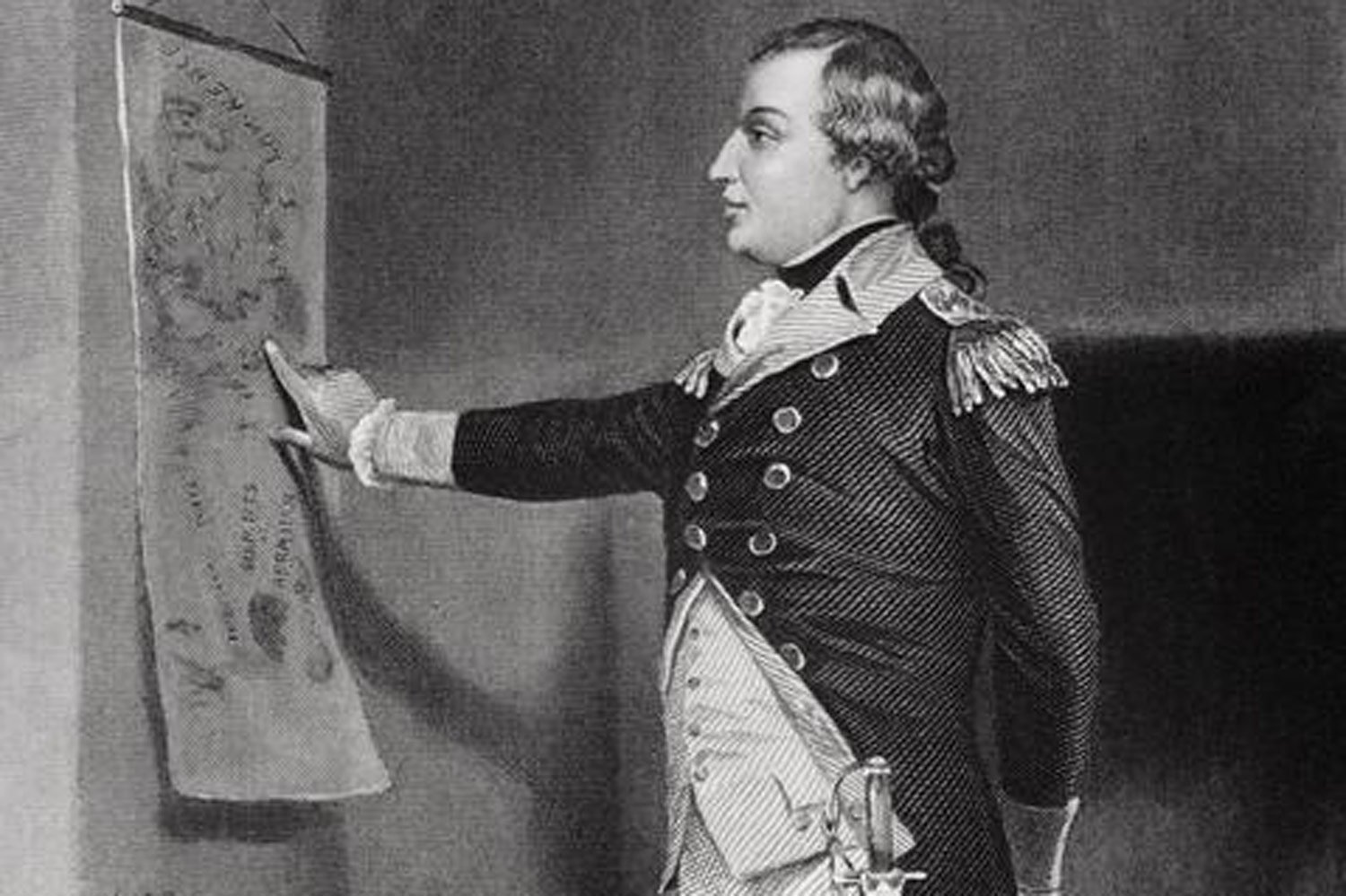

General John Burgoyne had captured Fort Ticonderoga on July 6 and was advancing south. General George Washington requested that Congress send his most trusted field commander, Benedict Arnold to stop Burgoyne. Washington informed Congress that without Arnold “the most disagreeable consequences may be apprehended.”

The most successful battlefield commander in the American army during the early years of the American Revolution was Benedict Arnold. Between 1775 and 1777, Arnold helped capture a fort, led a miraculous trek, besieged a foreign city, fought a naval battle, led a relief force to lift a siege, and saved a battle that led to the surrender of a British army.

Benedict Arnold was one of the most complex men in American history. His meteoric rise from merchant to war hero and the subsequent fall from war hero to arch traitor is unparalleled in our nation’s history.

The Tryon County militia sent to relieve the siege of Fort Stanwix had been badly mauled at the Battle of Oriskany on August 6, 1777. The combined Loyalist and Indian contingent under British Lieutenant Colonel Barry St. Leger, settled back into its work of reducing the fort or forcing the American garrison to surrender.

By mid-September 1777, British General John Burgoyne, after crossing to the west bank of the Hudson River, was committed to continuing his advance towards Albany. There was only one road he could take to get there, and that road was strongly defended by an American army, twice as large as his own.

In the eight short weeks since capturing Fort Ticonderoga without a fight, British General John Burgoyne had seen his army go from being invincible to facing starvation and defeat. More bad news arrived on August 28, when Indians brought word that a relief force under Lieutenant Colonel Barry St. Leger coming from the west down the Mohawk River Valley had turned back.

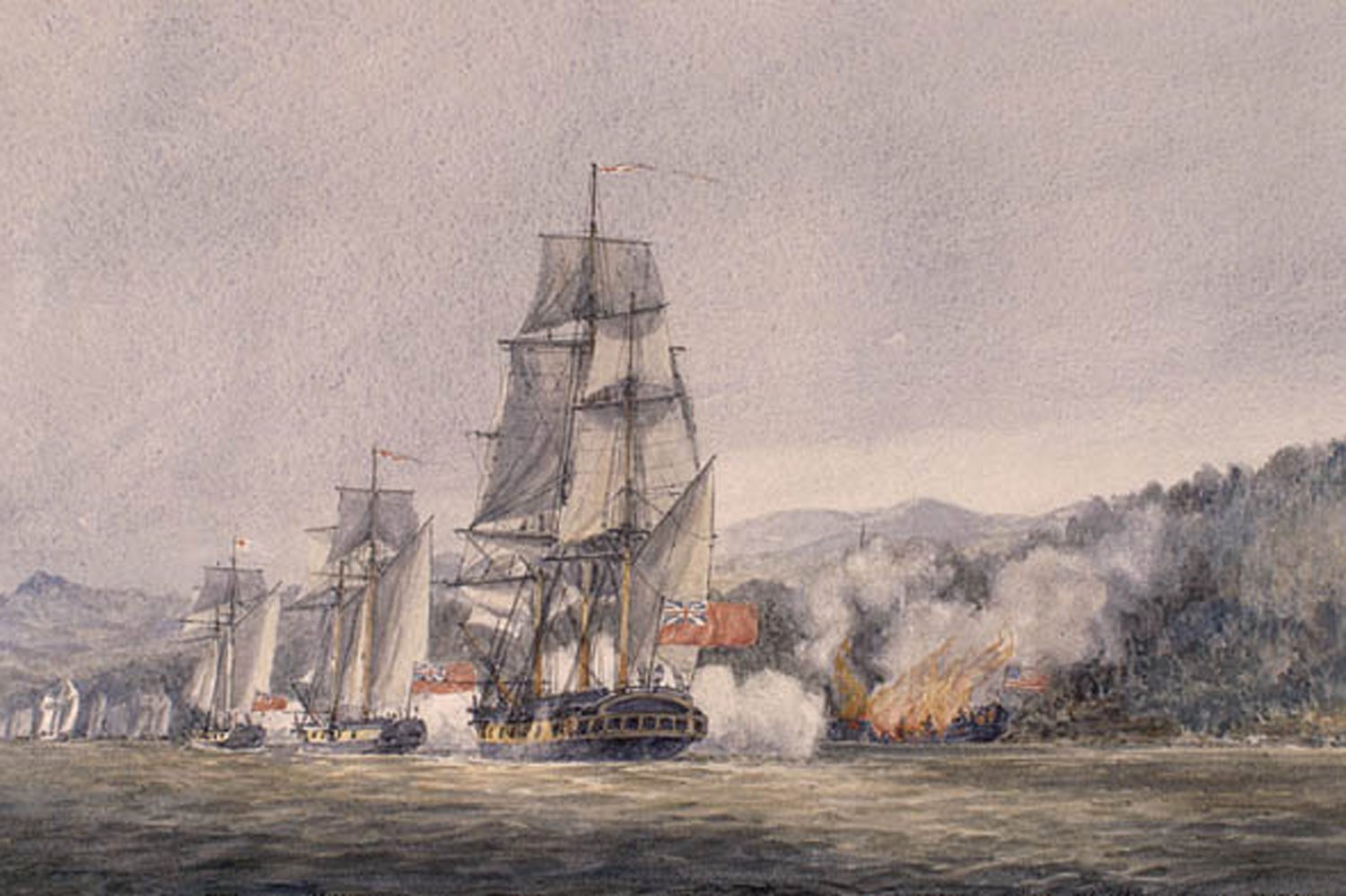

The Battle of Valcour Island, which took place on Lake Champlain, was the closing scene of the Northern Campaign of 1775-1776. It was one of the first naval battles of the American Revolution and, although a tactical defeat, it was a strategic victory for the American cause.

General Guy Carleton, the man in charge of British forces in Canada, chose to return to the safety of Quebec’s walls after repelling the American assault on the city instead of venturing out and attacking the remaining Americans. With the death of General Richard Montgomery, Colonel Benedict Arnold assumed command of the American army outside Quebec and, despite the setback, refused to give up on the conquest of Canada.

On December 26, General Richard Montgomery assembled the key officers in his army besieging Quebec City to discuss their next steps. The bombardment of the city had failed to convince British General Guy Carleton to surrender and there were only five days remaining until the enlistments of most of Montgomery’s men expired and they left for home. There was grumbling in the ranks that the retreat should have already started.

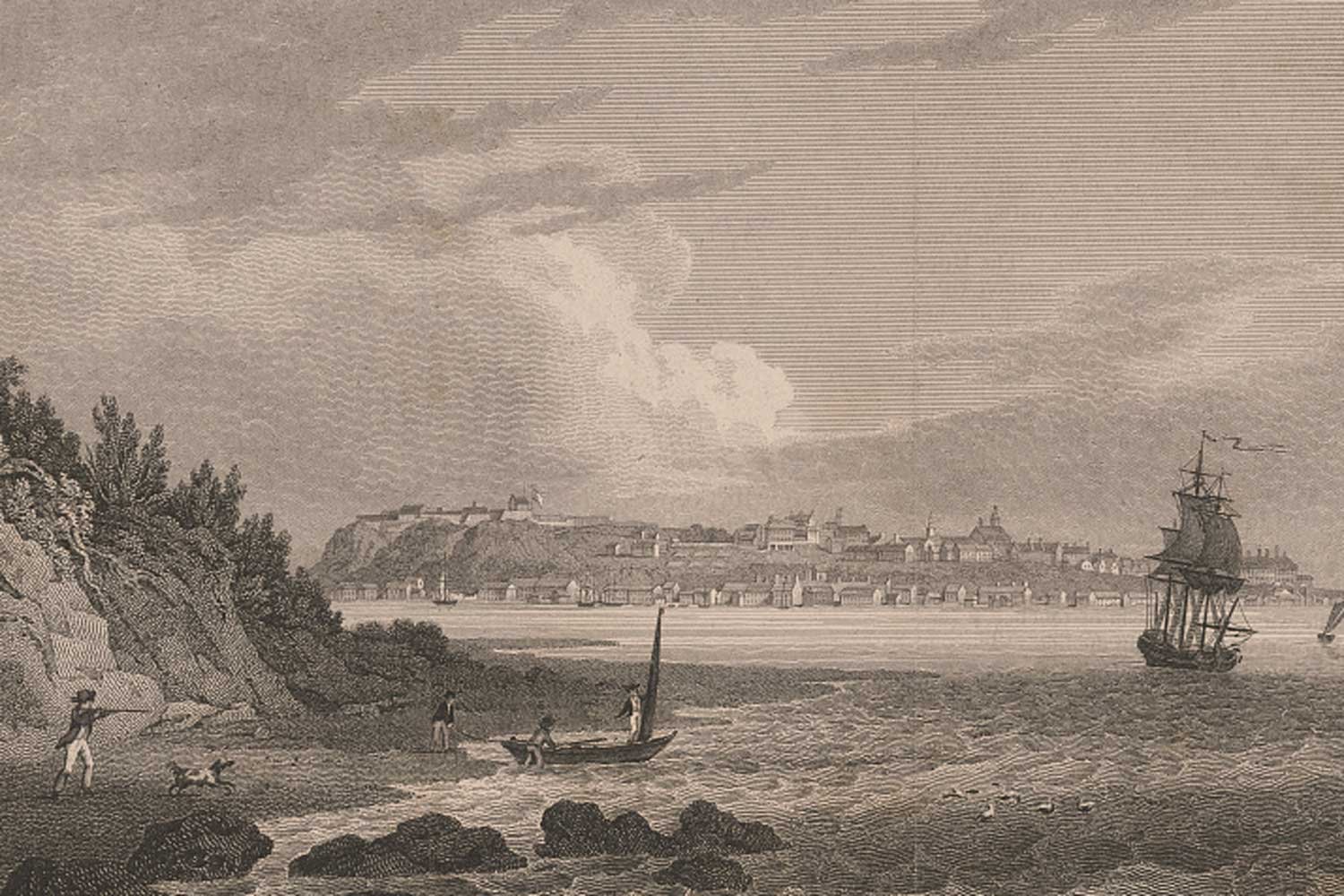

With the capture of Montreal by General Richard Montgomery and the presence of Colonel Benedict Arnold’s force of 600 men on the Plains of Abraham, Britain’s foothold in Canada had dwindled to about one square mile, the area within the mighty walls of Quebec City. Now the defenses of that fortress would be tested by a band of determined Americans.

After clearing the Height of Land, Colonel Benedict Arnold’s army on its way to capture Quebec City believed they were on the downhill slope to their destination, but their hardships were not finished. The area which they just entered was poorly mapped, and Arnold’s regiments paid the price for this lack of knowledge.

When Colonel Benedict Arnold’s army reached the Great Carrying Place on October 11, 1775, they had been moving north on the Kennebec River for almost three weeks and had advanced eighty-four miles. The American militiamen were on their way to assault Quebec City, the crown jewel of British Canada. The time originally estimated for the entire journey to Quebec was about twenty days, and the anticipated distance was 180 miles. Neither Arnold nor the men were aware they had another 300 miles to go.

Benedict Arnold’s expedition to the gates of Quebec City in the fall and winter of 1775 is widely regarded as one of the greatest military marches in history. Arnold, despite his sullied reputation due to his traitorous behavior later in the war, was one of America’s most gifted field commanders, and his tremendous leadership skills were put to the test on this perilous journey.

The first significant offensive operation of the American Revolution was the largely forgotten invasion of the Province of Quebec by American troops in 1775. It was the opening act of the greater Northern Campaign of 1775-1776 in which the American colonies tried to wrest control of Canada from England. Although it did not end well, there were moments of incredible bravery and perseverance that demonstrated the resolve of our founding generation.

Fort Ticonderoga in upstate New York is arguably the best-preserved fort from the 1700s in North America. It was the site of several engagements in both the French and Indian War and the American Revolution. Its military significance is matched only by the natural beauty that surrounds the site.

Lieutenant Colonel John Jameson, who commanded the unit that had captured the British spy Major John Andre, ordered an aide to take word to General Benedict Arnold about Major John Andre’s capture. He sent another aide to find and inform General George Washington as well.