The Bill of Rights: First Amendment - Assembly and Petitioning

The First Amendment: Congress shall make no law respecting an establishment of religion, or prohibiting the free exercise thereof; or abridging the freedom of speech, or of the press; or the right of the people peaceably to assemble, and to petition the Government for a redress of grievances.

Beyond the freedoms of religion and speech we previously discussed, there are two other equally important rights granted to the people in the First Amendment that receive less fanfare. These are the rights to peaceably assemble and to petition the government to correct a wrong.

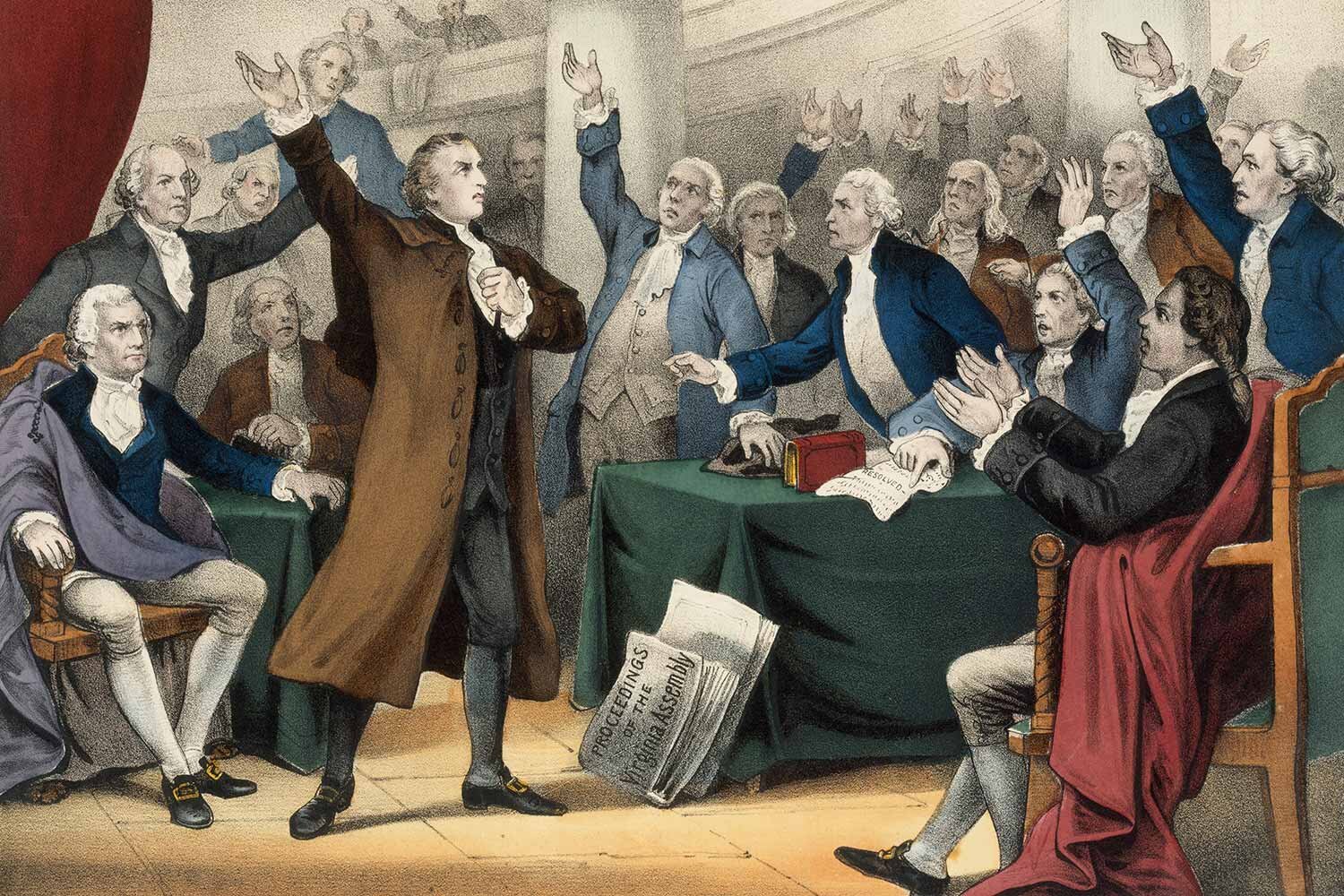

Prior to the American Revolution, many American colonists had issues with the laws and taxes imposed by Parliament on the colonies. To draft a unified response to England, meetings were held in numerous locations. However, King George declared those gatherings to be illegal.

When creating the Bill of Rights, the Founders wanted to ensure that this essential right would not be restricted. They recognized that meetings to discuss important topics of the day, both at the local and national level, were critical to a republican form of government. Events from town hall meetings to civil rights marches take place because of this provision.

It is important to note that when James Madison drafted this amendment, he included the word “peaceably” in this clause to emphasize that this right did not extend to violent protests and rioting. While the right to assemble was guaranteed, what people did while they met and how they conducted themselves mattered.

The right to petition the government for a redress of grievances, as originally imagined by the Founders, essentially meant that the people could take their complaints to elected officials and seek to have their issues resolved. This concept has greatly expanded over the years.

When Madison submitted his proposed wording for this clause, he specifically only mentioned citizens “applying to the Legislature…for a redress of their grievances”. The Founders believed many requests would be made by individual people directly to Congress to change a law.

However, Madison also understood that groups of citizens with a common interest might bring a petition to elected officials. He worried about the power of these “factions” overly influencing government. Madison described these factions as “a group of citizens…actuated by common impulse of passion or desire”, essentially the precursor of today’s “special interests”.

As explained in Federalist No. 10, Madison felt it would be nearly impossible to eliminate factions, but he believed they could be thwarted if factions had to compete with other factions for control.

Since our founding, especially with the growth of our administrative state, the Supreme Court has expanded this right of petitioning to include all three branches of government, and to allow citizens and groups to file legitimate lawsuits against them. Perhaps most importantly, numerous court decisions have confirmed the legality of lobbying by individuals, groups, and corporations.

Initially, lobbying took place in state assemblies because the federal government did not get as involved in economic matters and most legislation came from the states. Starting in the 20th century, this practice has significantly increased at the federal level as Washington has taken on a greater role in our daily affairs.

WHY IT MATTERS

So why should it matter to us today that Congress can make no law that restricts “the right of the people peaceably to assemble, and to petition the Government for a redress of grievances”?

From the suffragettes of the early 20th century to the civil rights marchers of the 1960’s, peaceful assemblies allow the people to marshal their resources to fight injustice. In much the same way, our right to take petitions directly to the halls of Congress is critical to preserving our interests. The importance of these rights cannot be overstated and should not be taken for granted by citizens today.

SUGGESTED READING

A great literary resource for many of America’s most important documents, speeches, and letters is a book published in 2017 by Canterbury Classics called “The U.S. Constitution and Other Writings”. The hardcopy book has both the current US and the “Betsy Ross” flags on the cover and the Liberty Bell on the spine. It is the most beautiful hardcopy book cover I have ever seen.

PLACES TO VISIT

If you get the chance, you must visit Boston National Historical Park www.nps.gov/bost/index.htm in downtown Boston. This site includes many beautifully preserved buildings where our nation’s history happened, including Old North Church, Old South Meeting House, Paul Revere’s home, and Faneuil Hall.

Until next time, may your motto be “Ducit Amor Patriae,” Love of country leads me.

The Tenth Amendment is one of the true foundational amendments of our Constitution. It reserves for the states all rights not granted to the national government by the Constitution, guaranteeing a federalist type of administration.