British Capture Savannah

In 1778, after three years of fighting their rebellious American colonists, the grand British Army had been stymied in the northern theater. At this point, Lord George Germaine, secretary of state for the American Department, decided to focus his efforts southward, having been repeatedly informed by exiled American Loyalists that Georgia and the two Carolinas were heavily populated by Loyalists simply waiting for assistance from the British Army. On December 29, a British force led by Colonel Archibald Campbell captured Savannah, effectively gaining control of Georgia.

Tom Hand, creator and publisher of Americana Corner, discusses Germaine’s strategy towards the southern colonies, and why it still matters today.

Images courtesy of Architect of the Capital, British Museum, Library of Congress, Brown University Library, New York Public Library, National Army Museum, National Gallery of Art, Wikipedia.

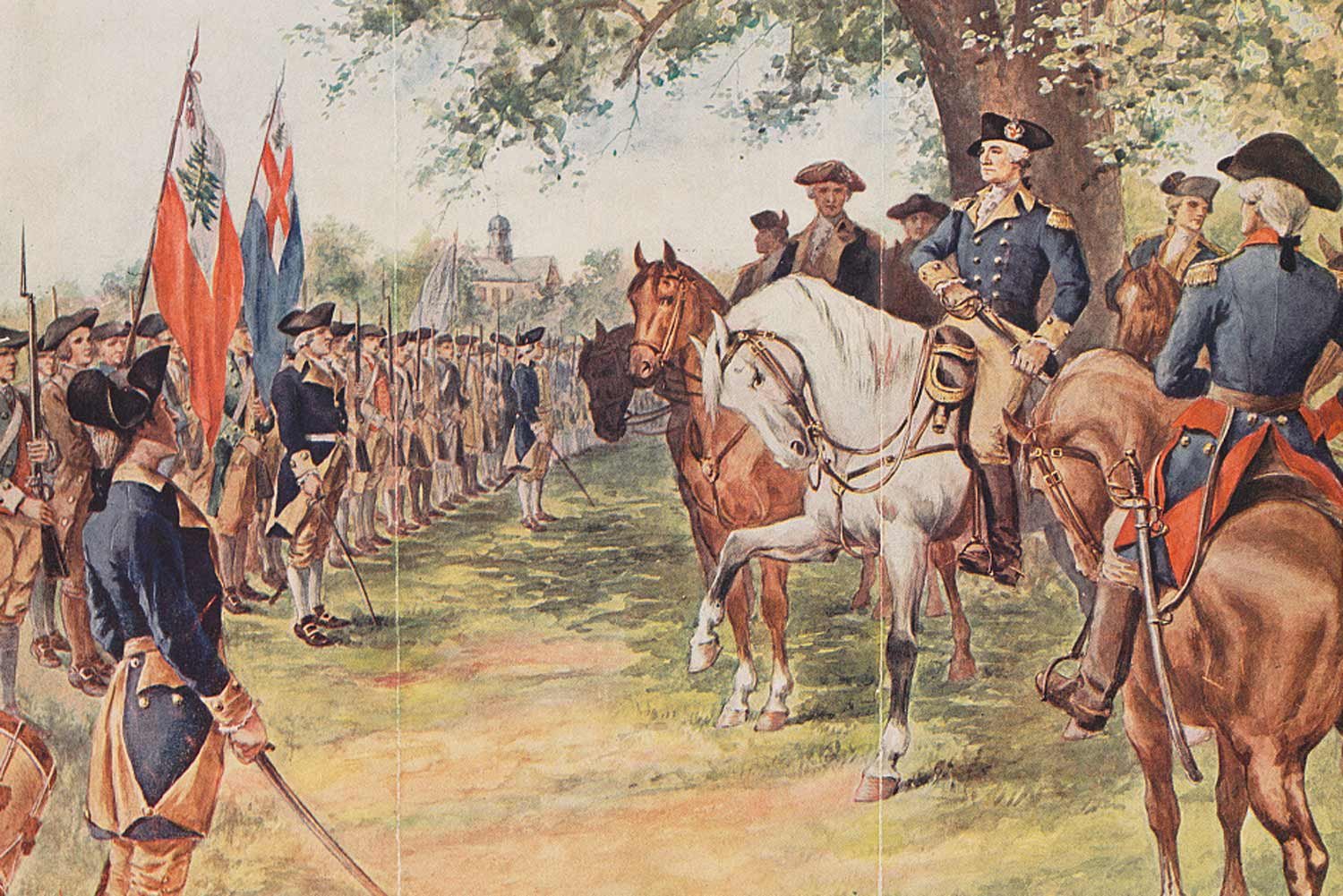

General George Washington led his Continental Army and the French Army under General Jean-Baptiste de Rochambeau into Virginia in mid-September 1781. The combined force was on its way to Yorktown and its appointment with destiny with the entrapped British command of General Lord Charles Cornwallis.

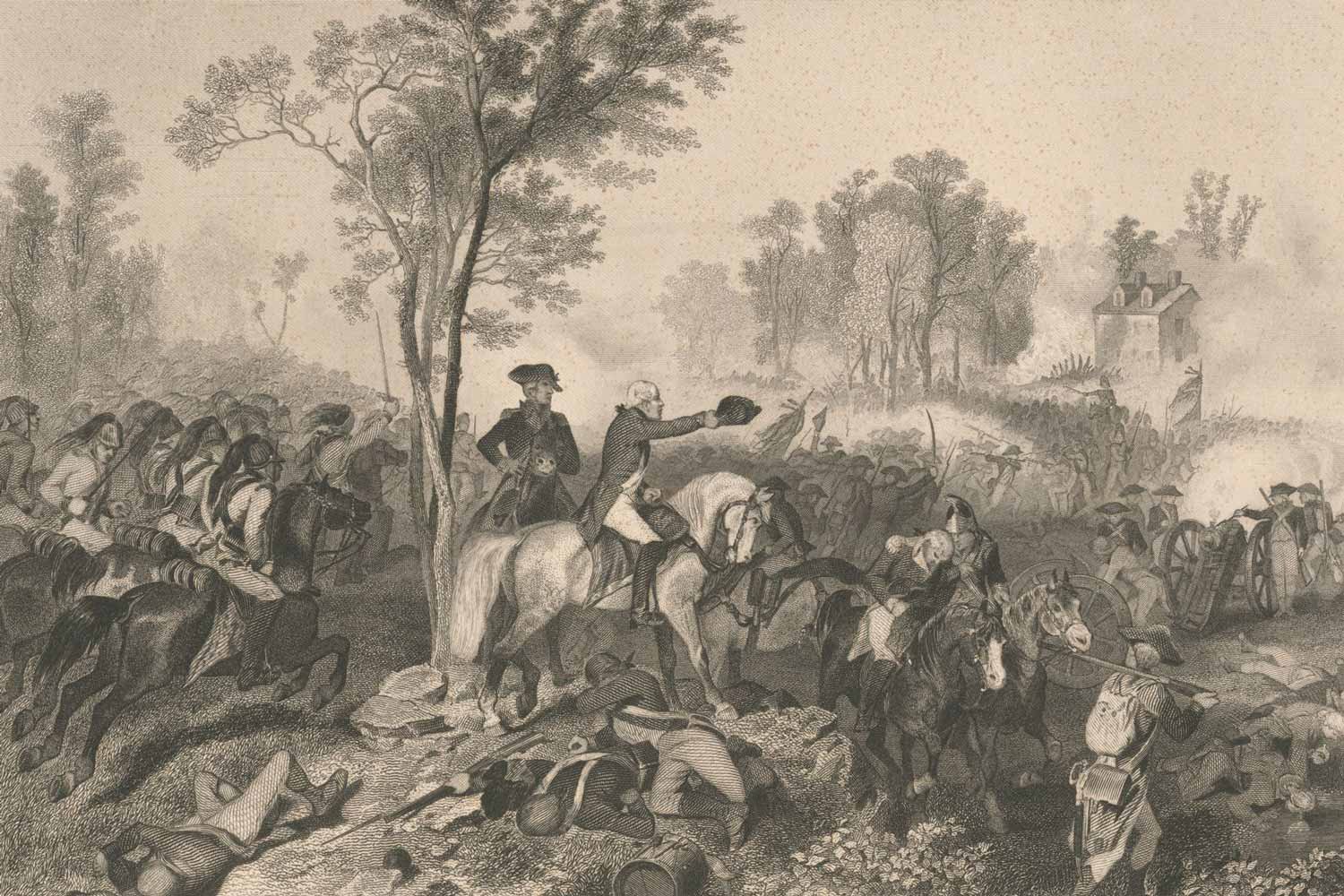

After the Battle of Monmouth Courthouse in June of 1778, the British retreated into the friendly confines of New York City. Following two lengthy campaigns (New York in 1776 and Philadelphia in 1777), England had neither crushed the Continental Army nor roused the local populace to join the British effort.

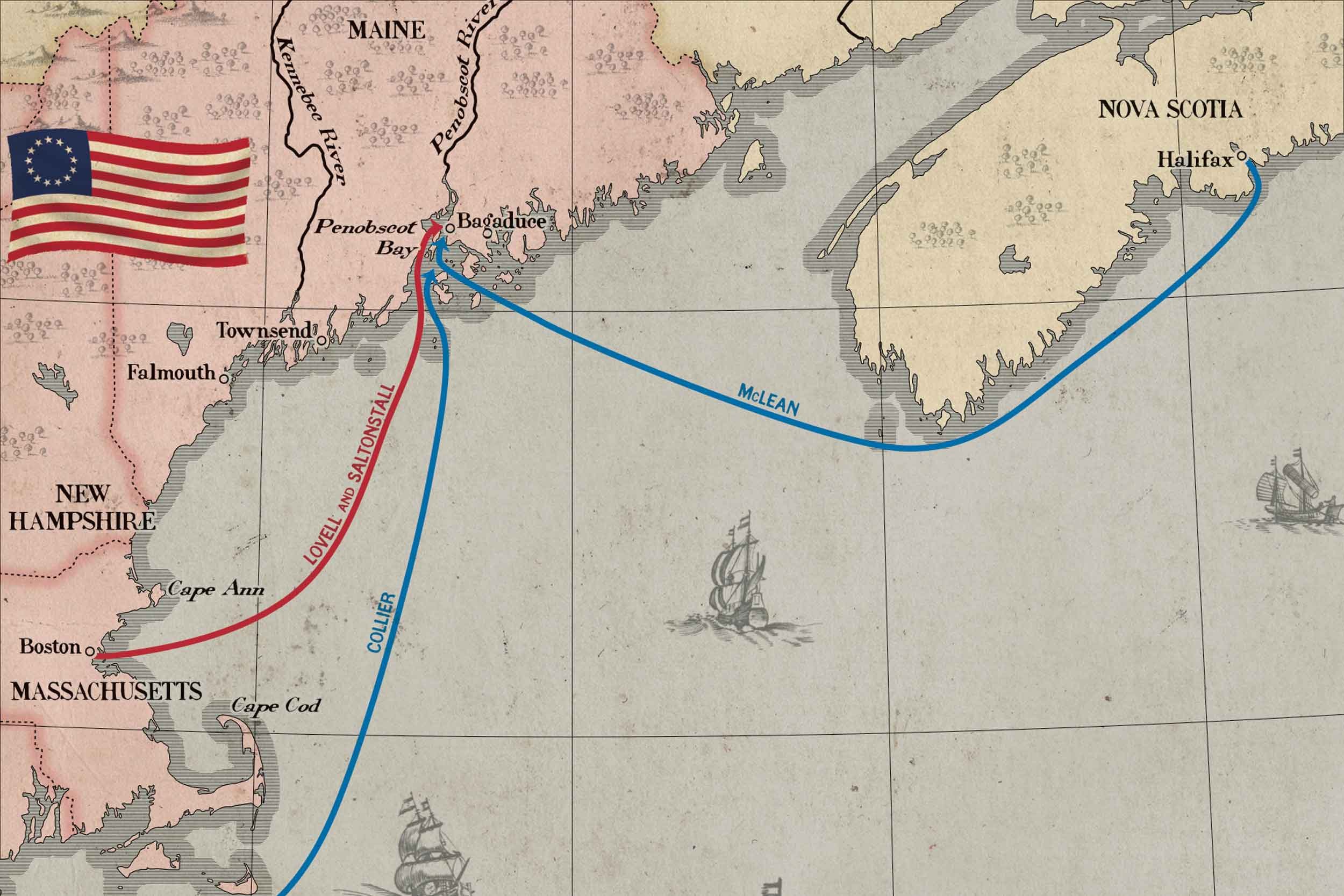

As morning broke on August 17, 1779, Vice-Admiral Sir George Collier, the commander of the small British flotilla inside Penobscot Bay, could hardly believe what had transpired over the past three days. Arriving with the expectation of a stiff fight from an American fleet much larger than his own, no battle ever materialized as the American commanders chose self-destruction to facing British guns.

As darkness fell in Penobscot Bay on August 13, 1779, the American soldiers and sailors in Penobscot Bay realized they were trapped by the newly arrived British fleet under Admiral Sir George Collier. With disaster staring them in the face, General Solomon Lovell, commander of the militia, and Commodore Dudley Saltonstall, the navy commander, displayed an energy that had been absent for much of the past three weeks.

The Penobscot Expedition which started so well with the successful assault up the cliffs at Dyce’s Head to the plateau at the top of the Bagaduce Peninsula on July 28, quickly ran out of steam. Three main impediment was an inter-service squabble between the army commander, General Solomon Lovell, and his naval counterpart, Commodore Dudley Saltonstall. Showing a reluctance to engage the enemy that seemed to border on cowardice, Saltonstall would be an obstacle that Lovell could not overcome.

In June 1779, with the British establishing a foothold in Penobscot Bay 240 miles northeast of Boston, the Massachusetts General Assembly sprang into action. The men chosen by the Assembly to lead the expedition to oust the Brits was an interesting group, all New Englanders and not a professional soldier among them.

The greatest naval disaster in our nation’s history until Pearl Harbor was a largely forgotten episode that took place on the remote coast of Maine in the summer of 1779. The location was Penobscot Bay and the event proved to be an embarrassment caused by ineptitude, cowardice, and lost opportunities.

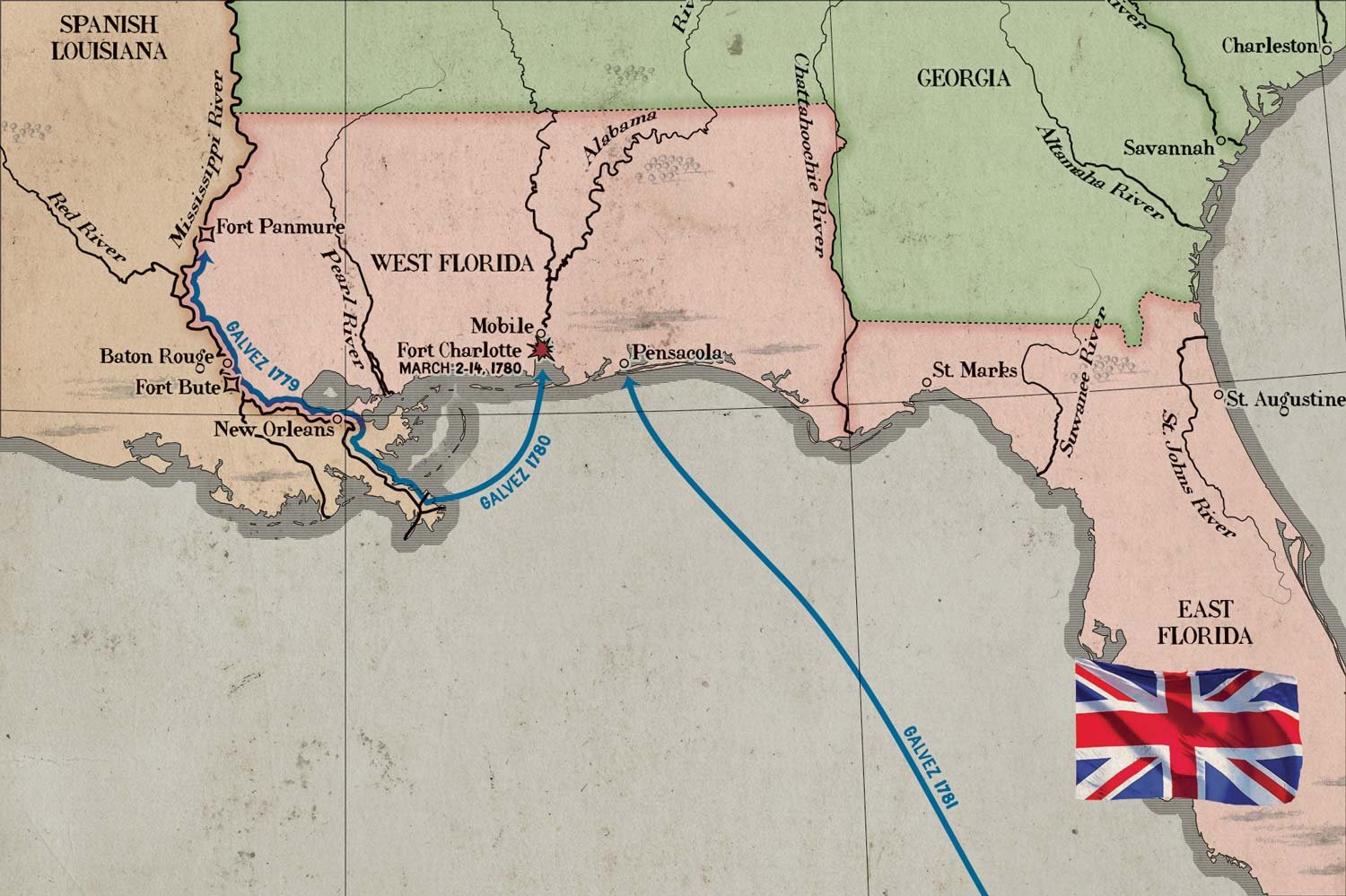

Because of Spain’s numerous possessions along the Gulf Coast and in Central America, France and Spain jointly decided to have Spain fight the British throughout the southern theater and in the Mediterranean, while France would send their soldiers and navy to help the thirteen American colonies. It is the reason why the French were at Newport, Savannah, and Yorktown while Spanish soldiers were not, leaving the mistaken impression in most American’s minds that France was our only ally in the American Revolution.

With British fortune in the American Revolution at low tide in 1779, King Carlos III of Spain and his chief minister Jose Monino, Count of Floridablanca, decided the time was right for Spain to enter the war. But, for strategic reasons, they did not do so as a formal ally of the United States, but rather as one of France, their neighbor and cousin. As time would tell, Spain’s decision was instrumental in securing American independence.

The United States’s only formally declared European ally in the American Revolution was France, but it also had an undeclared friend in Spain. While France is the country most Americans associate with American independence, Spain played a significant role as well, arguably even more critical than France.

The Treaty of Paris was signed on September 3, 1783, officially ending the American Revolution and granting independence to the United States of America. Perhaps more importantly for the settlers in Kentucky, the treaty brought an end to the steady stream of English guns and gunpowder to the Indians that had relentlessly attacked Kentucky during the war.

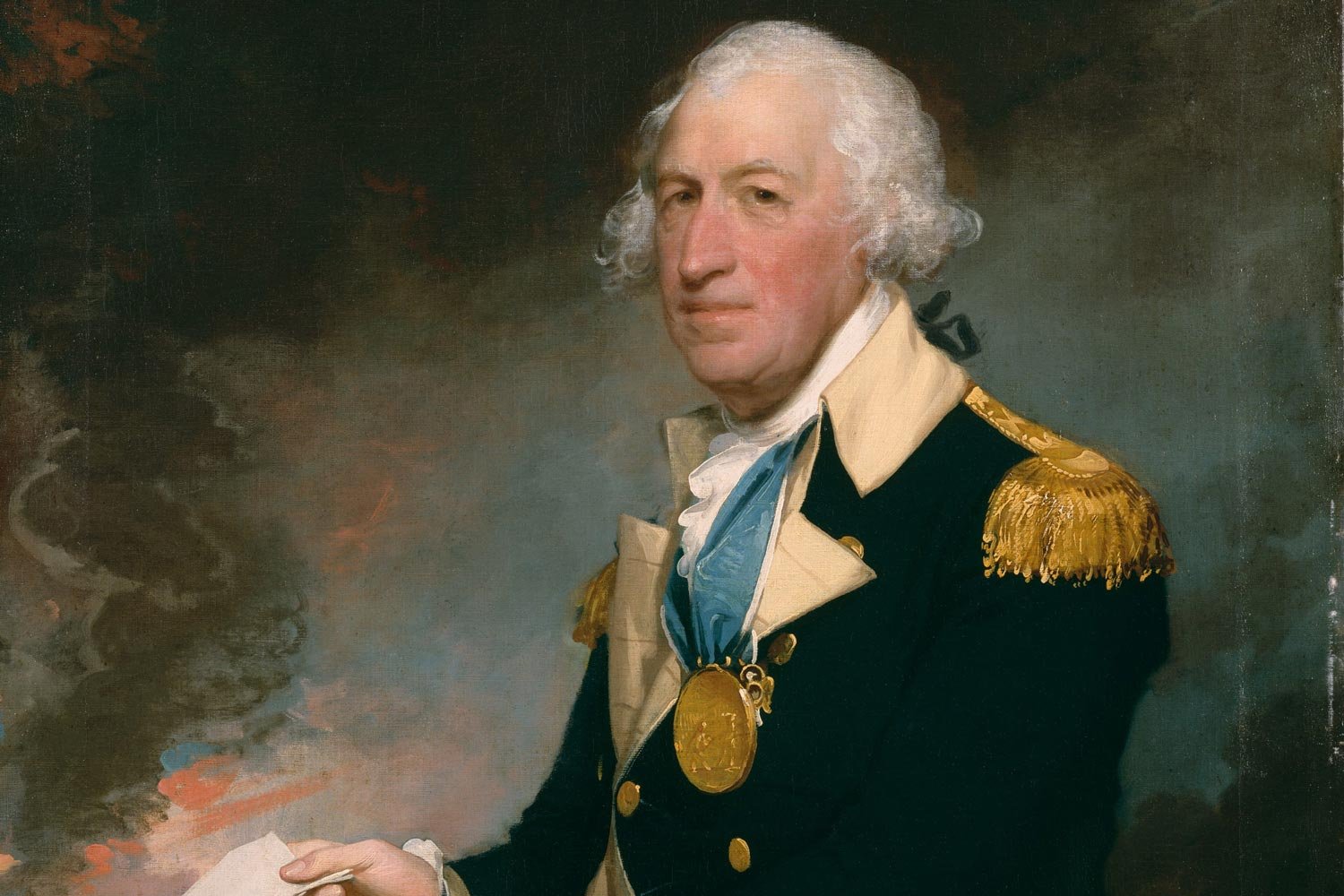

Nathanael Greene was truly the savior of the south, and significantly responsible for winning the American Revolution. His contemporaries recognized this fact, and awards, accolades, and even land grants were given to Greene.

By the late summer of 1781, the American Revolution in the south was drawing to a close. Hoping to inflict more damage to the British, Major General Nathanael Greene, the commander of the southern Continental Army, planned a strike at the one remaining British army in South Carolina.

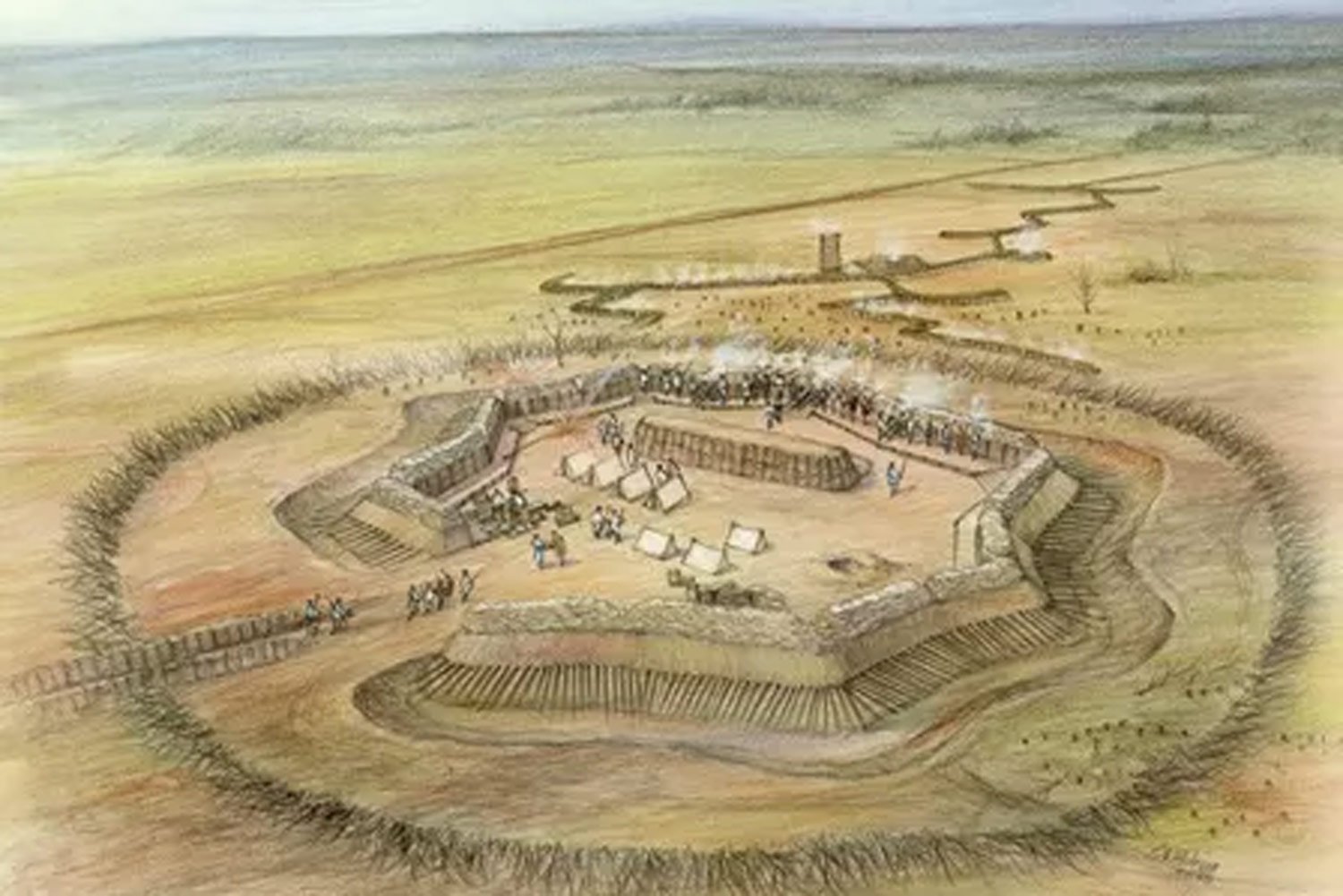

In the spring of 1781, American forces under General Nathanael Greene rolled up the British garrisons in the interior of the Carolinas one by one. The last British holdout was the fortified town of Ninety Six, in the foothills of western South Carolina. Greene arrived on the scene with 1,000 men and commenced the siege of Ninety Six on May 22.

When General Nathanael Greene crossed the Dan River and escaped to Virginia on February 14, 1781, Lord Charles Cornwallis’s British army controlled all of North Carolina, and most of South Carolina and Georgia. Within the short span of seven weeks, all that would change.

Following the successful conclusion of the Race to the Dan, General Nathanael Greene and his southern army was safe for the moment from the British troops under Lord Charles Cornwallis just across the river. Due to a lack of supplies in the area, Cornwallis retreated to Hillsboro, about sixty miles southeast, to get refitted. By late February, Greene had received reinforcements, recrossed the Dan, and had the American army back in North Carolina.

The Battle of Cowpens on January 17, 1781, was a great victory for Daniel Morgan and his army of Continentals and militiamen. They had virtually annihilated Lieutenant Colonel Banastre Tarleton’s famed British Legion, but Morgan’s contingent was in a dangerous position, with a larger British force under Lord Charles Cornwallis only twenty-five miles away. The race was now on to get to a place of safety.

Daniel Morgan came out of his self-imposed retirement and returned to the Continental Army near Hillsborough, North Carolina in late September 1780. He felt he could no longer sit on the sidelines while his country was at war. In December, Major General Nathanael Greene sent newly promoted Brigadier General Morgan and 600 men west to threaten British outposts in western SC.

Daniel Morgan was inspired by America’s desire for independence as early as 1774, when England imposed the Intolerable Acts on the colony of Massachusetts. Morgan felt a natural resentment to this imposition of British authority, tracing back to his unpleasant experiences serving the British army as a wagoner during the French and Indian War.

Daniel Morgan, the victor of Cowpens, was one of America’s best battlefield tacticians during the American Revolution. He rose from a hard scrabble childhood to national prominence solely on his merit and ability, overcoming his lack of political connections and wealth. Morgan’s story is a truly inspirational tale.

Despite the disastrous defeat at King’s Mountain on October 7, 1780 and several victories by Patriot partisans, Lord Charles Cornwallis and the British army still controlled most of South Carolina and Georgia at end of 1780. The new year would see a reverse of fortunes for the American cause as two gifted commanders, Major General Nathanael Greene and Brigadier General Daniel Morgan, took the helm of the southern Continental Army.

Nathanael Greene was one of the greatest American generals to emerge from the American Revolution. Without any formal military training or any experience, Greene developed into a leader feared and respected by his British counterparts.

This Continental Army General’s family arrived in America in the mid-1600s and soon became prominent and prosperous in their region. As a youth, he had little formal education but managed to find time to study great military leaders of the past. During our War for Independence, he lost most of the battles he fought but managed to hold his thread-bare regiments together.

In July 1780, Patriot partisan bands in the backcountry of South Carolina launched a series of successful attacks on Loyalist contingents, weakening the British hold on the state. These rapid-fire engagements continued into August as six more Patriot partisan victories were sandwiched around the disastrous Continental Army defeat at Camden and the capture of an American supply train at Fishing Creek.

As dawn broke on the morning of August 16, 1780, the British army under Lord Charles Cornwallis and the American southern army under Major General Horatio Gates were half a mile apart, preparing to do battle. It would be a short affair, but a costly one for the Americans.

The surrender of Charleston and its entire 5,000-man garrison on May 12, 1780, essentially eliminated the American southern Continental Army. At that point, Lord Charles Cornwallis and his British legions were able to operate virtually unopposed in South Carolina.

For the first five years of the American Revolution, the deep southern states of Georgia and the two Carolinas were mostly observers of the conflict. Other than a failed attempt to take Charleston in 1776 and the capture of Savannah in December 1778, the British had focused their efforts in the north.

The first time a Royal Governor of a British American colony called out the troops to suppress rebellious American subjects was not the famous fight at Lexington and Concord in 1775. The initial incident of this sort occurred four years earlier when the Royal Governor of North Carolina, William Tryon, suppressed a grassroots effort known as the Regulator Insurrection.

Following General Benjamin Lincoln’s surrender of Charleston on May 12, 1780, Sir Henry Clinton, the British commander, offered a full parole to the captured Americans as long as they remained neutral. The other American garrisons in the state at Ninety Six, Camden, Beaufort, and Georgetown were extended these same terms.

After Lord Charles Cornwallis surrendered to General George Washington in Yorktown on October 19, 1781, English officials reached the painful conclusion that the war was simply too costly to continue. Not only was the war in North America expensive to prosecute, but it was also a distraction from England’s defense of their more lucrative possessions elsewhere in the world, such as the sugar islands in the Caribbean and trading posts in India.