The Barbary Wars, Part 2: The Philadelphia is Lost

Soon after Thomas Jefferson was sworn in as our country’s third president on March 4, 1801, Yusuf Karamanli, the Pasha of Tripoli, decided to renounce the existing treaty his North African province had with the United States. Unhappy with the amount of his annual tribute and feeling under-compensated compared to his fellow tyrant, the Dey of Algiers, Karamanli demanded that the new president give him a one-time gift of $250,000 and an annual tribute of $20,000. But Karamanli, who had murdered his older brother to become Pasha, found out that Jefferson was a man of strong resolve where the honor of the United States was at stake.

On May 10, 1801, even before President Jefferson responded, Karamanli decided to declare war on the United States; Tripoli had recently concluded a peace with Sweden and the Pasha needed to be at war with someone to keep his corsairs gainfully employed. Karamanli was colorful and, instead of simply informing the United States Consul, James Cathcart, of his decision, Karamanli had his henchmen cut down the embassy flagpole from which the Stars and Stripes flew and immediately sent out his corsairs in search of American merchantmen. But Jefferson was one step ahead of his Muslim rival and, on June 1, Commodore Richard Dale and a small fleet of American frigates (President, 44 guns, Philadelphia, 36, Essex, 32) and the schooner Enterprise, 12 guns, cleared Hampton Roads and sailed for the Mediterranean, arriving on station in early July. Dale imposed a blockade of Tripoli and Karamanli soon asked Cathcart about a truce, which the Americans declined knowing the Pasha was just buying time.

Gilbert Stuart. “Commodore John Rodgers.” Naval History and Heritage Command.

The following month, Enterprise, commanded by Lieutenant Andrew Sterrett, in the first engagement of the Barbary Wars, engaged the 14-gun Tripolitan warship, Tripoli, and, following a three-hour fight, forced its surrender. In May 1802, as Dale’s time in command ended, Captain Richard Morris was sent as his replacement, and he brought with him an additional five frigates. The fleet included the ill-fated Chesapeake, 36 guns, the New York, 36 guns, with the soon-to-be-famous Stephen Decatur as its first lieutenant, the Adams, 28 guns, with future War of 1812 heroes Oliver Hazard Perry and Issac Hull as junior officers, and the John Adams, 28 guns, commanded by Captain John Rodgers, one of the truly great naval captains in our country’s history. Despite this star-studded cast and the increased firepower, Morris proved to be a dilatory leader and the blockade he imposed was largely ineffective. Frustrated by Morris’s inactivity, the secretary of the navy, Robert Smith, relieved him and Morris sailed home in September 1803. Upon his arrival, Morris faced a court of inquiry which found “Captain Morris did not conduct himself in his command of the Mediterranean squadron with the diligence or activity necessary to execute the important duties of his station.”

Morris’s replacement was Captain Edward Preble, who would prove to be all that Morris was not. Preble was born in Falmouth (today’s Portland) Maine in 1761 and had run away from home at age sixteen to go to sea as a privateer. He had served ably in the American Revolution and the Quasi-War and was selected for this assignment over the heads of several senior naval officers. Preble arrived at Gibraltar in September 1803 in his flagship, Constitution, 44 guns, and the following month sailed to the Moroccan capital of Tangiers and forced the emperor, who had begun to seize American ships, to sue for peace.

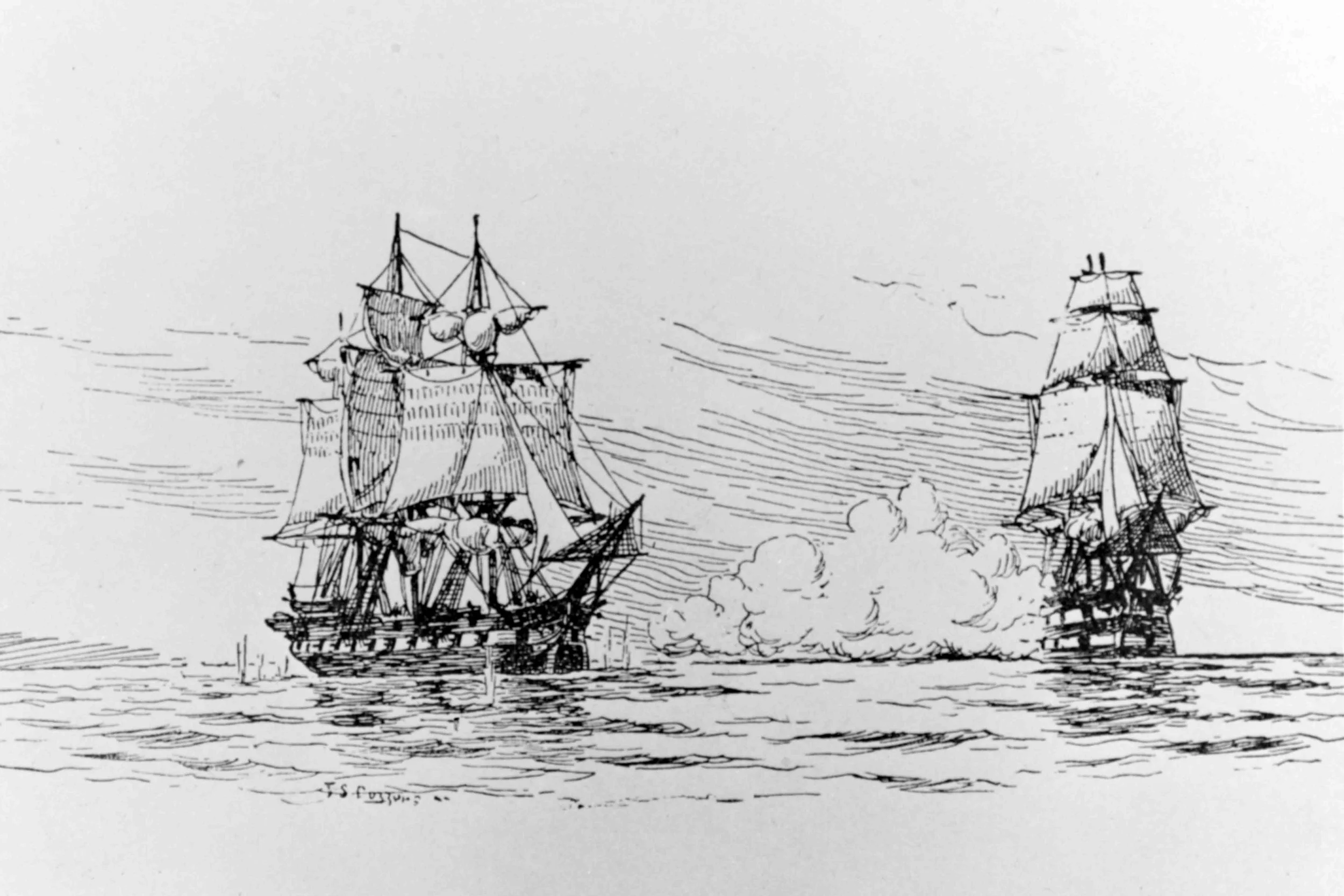

While Preble was making his show of force in Tangiers, Captain William Bainbridge in the Philadelphia was patrolling the waters off Tripoli along with the USS Vixen, enforcing the blockade reimposed by Preble. On October 31, Bainbridge spied a Tripolitan warship running for the safety of Tripoli harbor and gave pursuit. The Philadelphia closed the distance between the ships and opened fire with its bow chasers (long-range guns located at the front of a warship) before Bainbridge, concerned the ship was getting into shoal water (shallow water over a submerged reef), ordered Lieutenant David Porter cast lead-lines to determine the depth of the water. The readings showed the ship was in eight fathoms (forty-eight feet) of water while the boat only required about twenty, but Bainbridge still instructed Porter to turn the ship around and head out to sea. Unfortunately, Bainbridge’s order came too late, and the Philadelphia ran aground the Kaliusa Reef, uncharted on American maps.

With the ship’s bow several feet higher in the water, Bainbridge, one of the youngest captains in the Navy, immediately ordered all sail forward without determining the depth the water to his front. His goal was to force the ship over the reef, but his decision only made matters worse as the Philadelphia moved further on the reef and higher out of the water; it was now really stuck and could not be moved. The 307-man crew leapt into action and tried several remedies to free the ship. They first tried to reverse the sails and back the Philadelphia up, but this action only caused the ship to lean badly to its left, to the point where the portside guns were aimed straight downward and almost touched the water while the starboard guns pointed at the sky, rendering the frigate practically helpless. By now, the Tripolitans noticed the Americans dilemma and the pursued became the pursuer and the corsairs began to move toward the Philadelphia. Frantically, the sailors tried to lighten the load by tossing ballast, three heavy bow anchors, and many of the 2,000-pound cannons overboard. All told, the desperate men, with dark visions of imprisonment in a Tripolitan prison in their heads, threw an amazing sixty tons overboard by hand and still the ship would not budge.

While the Americans desperately tried to free their vessel, the unthinkable began to seep into the minds of many, that their powerful frigate could be lost to the Tripolitan rabble.

Next week, we will discuss Lieutenant Stephen Decatur and the burning of the Philadelphia. Until then, may your motto be “Ducit Amor Patriae,” love of country leads me.

When the Democratic-Republicans came to power in the election of 1800, the Jefferson administration effectively shut down and disbanded both the United States Army and Navy. As a result, when American merchant ships were abused and seized as contraband of war on the high seas and in British and French ports during the Napoleonic wars, the United States was helpless to respond.