Americana Corner’s 250th Article Launches Barbary Wars Series

The Barbary Wars, Part 1: Pirates of the Mediterranean

The Treaty of Paris of 1783 that ended the American Revolution, brought the United States its long-desired liberty and independence from Great Britain. But with that separation came the loss of protection on the high seas for American merchant ships by the Royal Navy. And the removal of that security blanket had painful and expensive consequences for the young country which were first felt several thousand miles away, in the waters of the Mediterranean Sea.

For several centuries, the northern crescent of Africa had been controlled by the Ottoman Empire and consisted of several puppet states including Morocco, which bordered the Atlantic and, along with British-held Gibraltar, guarded the entrance to the Mediterranean Sea, Algeria, Tunis, and Tripoli which bordered Egypt to the east. Each of these states, known collectively as the Barbary States or Ottoman Tripolitania, were ruled by a despot whose official title was the “dey” or “pasha.” But regardless of their designation, they were ruthless to the core and derived their main revenue from seizing unarmed merchant ships, taking the crews prisoner, and offering to return them for a ransom payment, or, failing that, selling them into slavery. To avoid these depredations, the Barbary States extorted tribute payments from any European nation that wished to trade in the Mediterranean.

These practices had been employed by the Barbary corsairs since the beginning of the Age of Discovery in the 15th century, when more and more European merchants sought to expand their trade into distant markets. It is estimated that by 1800, over one million Europeans had been captured by these rouges of the high seas. Amazingly, paying this extortion money had gone on so long as to become the accepted way of doing business in the Mediterranean, and European nations large and small paid this tribute to these petty thieves rather than taking concerted action and removing the scourge. The actions, or lack thereof, of these European nations were both cowardly and dishonorable, and, quite naturally, the pashas felt contempt for them. This same disrespect was shown to American merchantmen as well once they began to ply the waters of the Mediterranean under the Stars and Stripes.

The first American ship seized by the pirates was the brig Betsey, taken by a Moroccan corsair in October 1784, and other captures soon followed. Due to the fierce competition between American and British merchantmen for the carrying trade of the Atlantic and Mediterranean, British officials encouraged these depredations of American ships. Lord Sheffield declared, “it is not probable the American states will have a very free trade in the Mediterranean, as it will not be in the interest of any of the great maritime powers to protect them there from the Barbary States.” And over the course of the next decade, few American merchant vessels sailed in the Mediterranean unless provided an escort by the European nation with whom they were trading.

Not surprisingly, the Founding Fathers had varied opinions on how best to deal with the growing threat to United States commerce from the Barbary States; should we submit and pay the annual tribute or resist and martially defend American rights? In 1786, Thomas Jefferson and John Adams were the Ministers to France and England, respectively, and physically much closer to the issue than members of the Convention government back in Philadelphia. Not surprisingly, the two future presidents held opposing views of the matter, and they shared their thoughts with each other in a series of fascinating letters. While Jefferson felt going to war to defend our national honor was the better policy, Adams favored striking a deal with the pashas and paying for peace. Ironically, when these two American icons became president, Adams took the country into an undeclared naval war with France known as the Quasi-War rather than submit to their depredations, while Jefferson willingly submitted to numerous insults from Great Britain, including the infamous Chesapeake-Leopard affair rather than go to war. Clearly, perspectives change with circumstances.

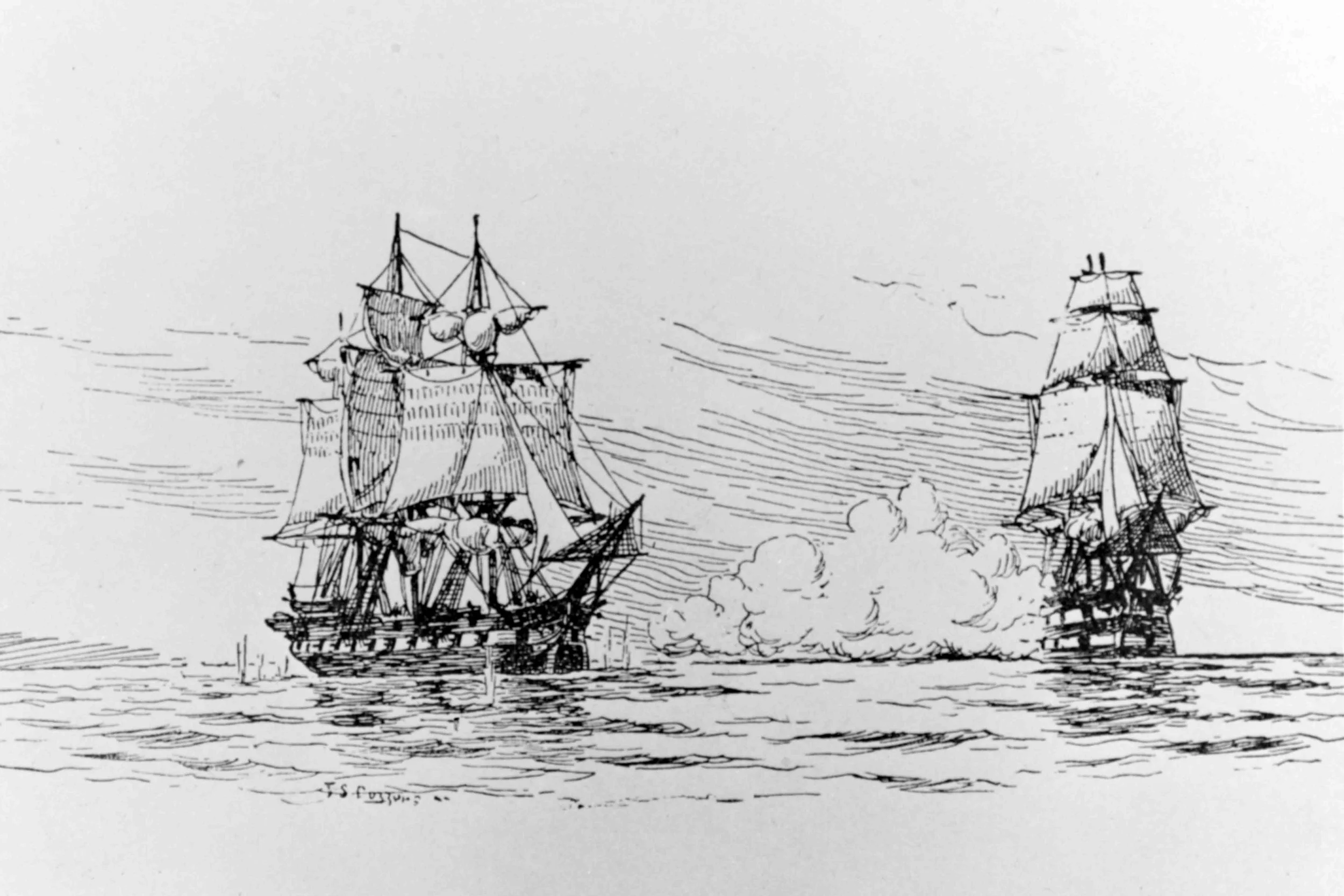

Frank Muller. “USS Chesapeake.” Naval History and Heritage Command.

In June 1786, the Confederation Congress, at the suggestion of Jefferson, sent Thomas Barclay to Morocco to obtain a peace treaty with Muhammad III, the nation’s ruler. Barclay was able to persuade the Sultan to agree to a treaty without the payment of any tribute, a rarity in any agreement with the Barbary States. This treaty, known as the Moroccan-American Treaty of Peace and Friendship, or Treaty of Marrakech, is still in existence today and is the longest lasting peace treaty in our country’s history. While this agreement settled matters with Morocco, the other Barbary States continued to be a menace to American shipping.

In 1793, after concluding a peace treaty with Portugal who had bottled up much of their fleet, the Algerian pirates began to attack American shipping and quickly captured eleven ships and 105 sailors. Recognizing something had to be done, President George Washington asked Congress to authorize the construction of a fleet powerful enough to protect American commerce in distant seas. On March 27, 1794, Congress passed the Naval Act of 1794 and agreed “to provide, by purchase or otherwise, equip and employ, four ships to carry 44 guns and two ships to carry 36 guns each” and from this legislation and these six frigates, came the birth of today’s United States Navy.

However, knowing that this burgeoning fleet was several years away from completion but the need to protect American merchantmen was immediate, in 1795 Congress ratified a humiliating treaty with Algiers that agreed to pay $1,000,000 in tribute and ransom to Hasan Pasha, the dey of Algiers, including an upfront lump sum, an annual payment, and four warships. The million dollars constituted an appalling 16% of federal revenue for the year, and the peace and protection it brought was short lived. As the Pashas of Tunis and Tripoli learned of the extraordinary amount the Dey of Algiers had extorted from the United States, they too wanted some of that easy American money and soon forced expensive and humiliating treaties on the young nation. But the Barbary States soon found out that they had pushed the United States too far.

Next week, we will discuss the United States Navy striking back. Until then, may your motto be “Ducit Amor Patriae,” love of country leads me.

When the Democratic-Republicans came to power in the election of 1800, the Jefferson administration effectively shut down and disbanded both the United States Army and Navy. As a result, when American merchant ships were abused and seized as contraband of war on the high seas and in British and French ports during the Napoleonic wars, the United States was helpless to respond.