The Barbary Wars, Part 5: U.S. Navy Triumphant in Tripoli

Commodore Edward Preble assembled his considerable American fleet just outside Tripoli harbor in August 1804, determined to punish the city and its corsairs, and force Yusuf Karamanli, the Dey of Tripoli, to sue for peace. It would not be an easy task as stout walls surrounded the city with one hundred and fifteen guns mounted on the battlements and over 25,000 Arab and Turk defenders within the walls. Moreover, the dey had aligned fifty guns on floating batteries in an arc nestled behind the reefs that extended across the northern entrance to the harbor.

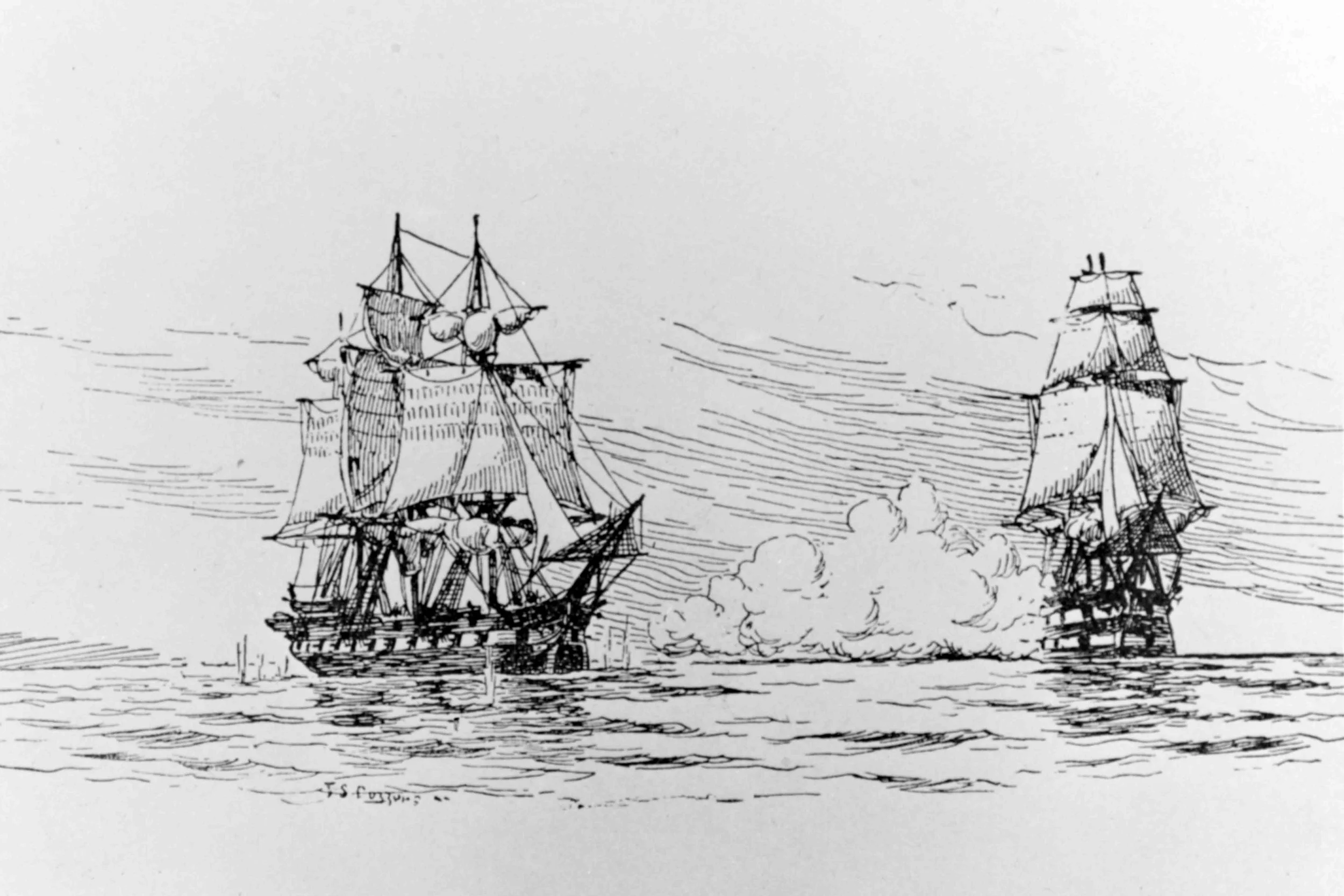

Although the shoal waters precluded Preble’s flagship Constitution from entering the harbor and pummeling Tripoli at point blank range, the other American ships mounted considerable guns, including 42 long 24-pounders to demolish the walls and 56 carronades for close range anti-personnel and anti-ship work. Preble’s initial assault came on August 3, sinking or capturing several Tripolitan gunboats and inflicting hundreds of casualties, while the Americans lost no ships and had thirteen men wounded. Unfortunately, they did suffer one death, that of Lieutenant James Decatur, the younger brother of Captain Stephen Decatur.

James had engaged a Tripolitan gunboat and forced its surrender, but upon boarding the boat, the Tripolitan captain shot James in the head, mortally wounding him, and then making his escape. Stephen, who had just captured a different gunboat, was informed of his brother’s death and he chased down his brother’s murderer. Decatur caught up with the boat and, despite being outnumbered, boarded her and personally killed the Tripolitan captain, avenging his brother. Interestingly, the Barbary pirates had gained a fearsome reputation for their intensity when boarding an enemy ship, and European ship captains tried to keep their distance from the corsairs as the Moslem pirates were considered invincible in hand-to-hand combat. With this action, the sailors of the U.S. Navy laid all that to rest and the Tripolitans never again allowed the Americans to get within boarding distance.

“Portrait of Commodore Edward Preble.” USS Constitution Museum.

Over the course of the next month, the American guns continued to pound Tripoli, pushing the Dey closer to submission. But in September, Captain Samuel Barron, several years senior to Preble, arrived on station and took over command of the Mediterranean fleet. Preble, greatly disappointed at not being able to complete his work, returned home in September to a hero’s welcome, including receiving a Congressional Gold Medal. Robert Smith, the Secretary of the Navy wrote, “We sensibly feel the value of your services and take pleasure in acknowledging them. Be assured that your country will never prove ungrateful. Nothing can deprive you of the reputation which you have justly acquired…by your conduct.”

By the end of the year, Barron’s fleet was the largest ever assembled under the American flag, including six frigates, four brigs, and three schooners, and the blockade grew ever more restrictive. As the noose tightened around Yusuf Karamanli’s neck, the Dey of Tripoli began to seek a way out of his dilemma and end the war on the best terms he could obtain. In December, Yusuf sent word via Spain’s consul to Tobias Lear, the American consul to Algiers, of his wish to open discussions. But the Dey’s initial demand called for $200,000 in ransom money for the release of all American prisoners and that the United States agree to compensate Tripoli for any losses incurred in the war; Lear ignored these outrageous terms.

After the Tripolitan city of Derne fell to General Eaton’s expedition on April 27, 1805, Karamanli became much more reasonable in his demands, knowing his capital city was next. Accordingly, Lear, who had been George Washington’s private secretary, sailed for Tripoli and negotiated an honorable peace that was signed on June 3. The final terms included an exchange of over three hundred Americans for one hundred Tripolitans and $60,000 for the disparity in the number of prisoners exchanged. Importantly, Karamanli agreed that the United States would no longer be expected to pay tribute to Tripoli, the first treaty of its kind ever reached with a Barbary State.

But old habits die hard, and the Barbary States had lost a great source of revenue by the bold stance taken by the United States. Consequently, soon after ascending the throne, the Dey of Algiers, Hadji Ali, began to make trouble. Early in 1812, as tensions increased between Great Britain and the United States, the British informed Hadji that the British Navy would protect the Algerians if they chose to attack the ships of Great Britain’s enemies. When the United States declared war on Great Britain later that summer, Algerian corsairs once again began capturing American vessels and, with the United States Navy occupied with British warships, the Madison administration was helpless to respond.

With the Treaty of Ghent ending the War of 1812, the U.S. Navy was available for deployment to the Mediterranean and President James Madison asked Congress for a declaration of war against Algeria. Two fleets were quickly assembled, one in Boston under Captain William Bainbridge and the other in New York led by Captain Stephen Decatur, which sailed first and arrived in the Mediterranean in mid-June. Decatur made quick work of his assignment and, over the span of six weeks, reached agreements with the Pashas of Algeria, Tunis, and Tripoli that the United States would never again be expected to pay tribute to the Barbary States, terms that Captain Decatur said were dictated “at the mouths of our cannon.” In an act of prudence and to keep these Ottoman provinces in line, the United States Navy maintained a presence in the Mediterranean until 1830.

When the country was young and powerless, it followed the long-held practice of European nations to pay tribute to the Barbary States as it was the easiest course to follow at the time. But even then, many Americans felt it was beneath the dignity of the United States to pay extortion money simply to sail unmolested on the high seas, a basic right of all nations. Before any other country, the United States took a principled stand against this tyranny and, by doing so, broke the spirit of the Barbary States.

Next week we will discuss the rise of the American judiciary. Until then, may your motto be “Ducit Amor Patriae,” love of country leads me.

When the Democratic-Republicans came to power in the election of 1800, the Jefferson administration effectively shut down and disbanded both the United States Army and Navy. As a result, when American merchant ships were abused and seized as contraband of war on the high seas and in British and French ports during the Napoleonic wars, the United States was helpless to respond.