The Barbary Wars, Part 3: “The Most Daring Act of the Age”

Captain William Bainbridge managed to run the USS Philadelphia hard aground on a submerged reef in Tripoli harbor on October 31, 1803, and this pristine frigate, one of the top ships in the United States Navy was now in grave danger of falling into the hands of the Tripolitan pirates. As the day dragged on, more Tripolitan gunboats joined the fray and, although not one shot struck the Philadelphia, the point remained that the frigate was listing badly to its left rendering its guns useless and the ship defenseless. Around 4:00pm, after consulting his fellow officers, Bainbridge made the painful decision to surrender and ordered the men to lower the Stars and Stripes. Soon, the Tripolitans were swarming over the deck and the entire 307-man crew were taken to shore where they were stripped of their clothes and crammed into a small prison chamber where they would remain for nineteen months, during which time six would die from maltreatment.

Captain Edward Preble received word of the loss of the Philadelphia in late November and, like the other Americans serving in the Mediterranean, viewed this event as a national humiliation and yearned to make amends somehow, either by recapturing the ship or destroying her. Plans were soon being developed and ideas exchanged by the officers of the fleet to redeem national honor. In the meantime, Yusuf Karamanli, the Pasha of Tripoli, notified American authorities that the ransom for the crew would be $1,690,000, more than the entire military budget of the United States. This demand was ignored by Preble as he continued to work on his strategy for freeing the Philadelphia. By late January, plans began to crystallize around Lieutenant Stephen Decatur and a captured Tripolitan ketch, Mastico, that had been renamed the USS Intrepid, an appropriate name as time would demonstrate.

Gilbert Stuart. “Stephen Decatur.” National Portrait Gallery.

Preble sent Decatur his instructions in a letter dated January 31, 1804, “It is my order that you proceed to Tripoli in company with the Siren, Lieutenant Steward, enter that harbor in the night, board the Philadelphia, burn her and make good your retreat with the Intrepid.” The Intrepid had been chosen because it was a Tripolitan vessel and could easily pass for a local merchant ship, especially at night when the attack was to take place, and the Siren as its escort ship because it had a low silhouette against the evening sky and was maneuverable in shallower waters. Decatur, a rising star in the young navy, was selected to lead the attack as he was a natural leader of men who maintained discipline through loyalty and respect instead of harsh treatment. Ironically, his father, Stephen Decatur, Sr. had been the first man to command the Philadelphia when it came off the blocks in 1799.

The plan was audacious and filled with risk as the Philadelphia was surrounded by a dozen Tripolitan warships riding at anchor, protecting their prize, and under the guns that guarded the harbor. It was as likely as not that the men sent to destroy the frigate and avenge the American prisoners would end up prisoners themselves. And yet, when the twenty-five-year-old Decatur asked for volunteers, every officer and sailor, and even the ship boys, stepped forward, and from this group Decatur selected five officers, five midshipmen, sixty-two sailors, and a Sicilian pilot who spoke the language and was familiar with the harbor.

On the evening of February 16, with a faint light from a new moon and suitable weather conditions, Decatur entered the harbor and the Intrepid slowly drifted to within one hundred yards of the Philadelphia, whose Tripolitan guards hailed the ship asking its intention. Salvadore Catalano, the Sicilian pilot, spoke to the guards in their own language and told them his ship had lost its anchor in the storm and requested that he be allowed to tie his ship to theirs for the night and they agreed.

As the Intrepid approached, the men on board were kept concealed except for a few who were dressed after the local fashion. When the Intrepid was about twenty yards away, the rope connecting the two vessels was secured. The hidden Americans began to slowly pull the two boats closer and, just before they touched, the Tripolitan guards suspected a trick and cried out “Americanos”. Their cry came too late and within seconds sixty daring American sailors, led by Decatur, swarmed over the decks of the Philadelphia. Soon, twenty Tripolitans were dead, and the rest jumped overboard, swimming to safety; the Americans suffered only one slight casualty.

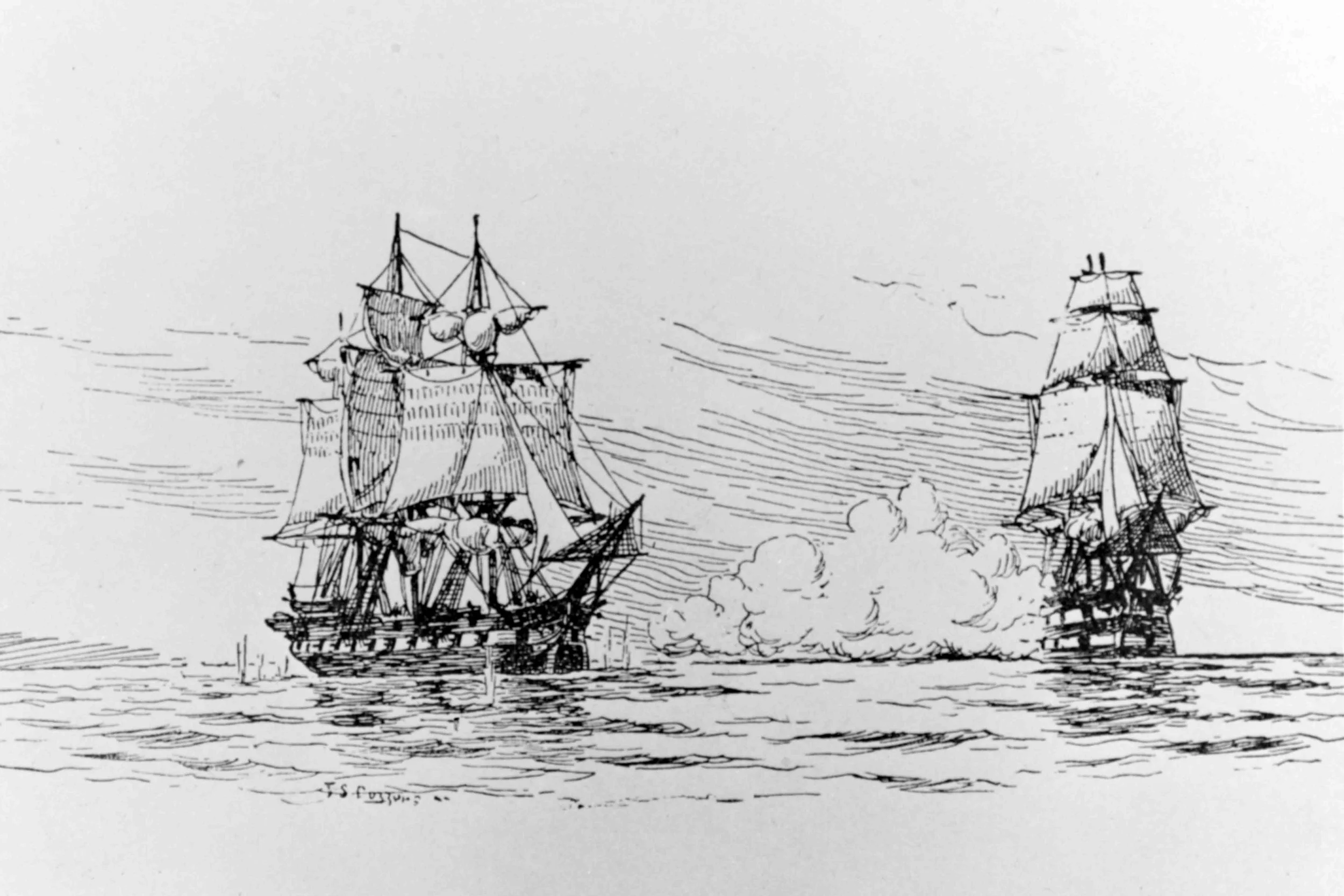

The combustibles and explosives were soon passed from the Intrepid to the men on the Philadelphia and strategically placed throughout the frigate in accordance with the plan. The frigate burst into flame so quickly the sailors barely had time to get back to the Intrepid, and, upon gaining the ship, they pulled on their oars as if their life depended on it. By now, the other Tripolitan gunboats were in a frenzy and, for the next half hour, over one hundred guns were fired at the fleeing Americans; amazingly, not one shot struck the hull of the ship. The guns of the Philadelphia which had been kept loaded by the Tripolitans began to heat amid the flames and discharge their rounds, many hitting the town. Later that night, the Philadelphia burned through its anchor cables, drifted ashore, and blew up; an inglorious end for this glorious battleship, but it had been heroically denied to the enemy.

As Midshipman Charles Morris, a participant who would go on to an illustrious naval career, wrote “The success of this enterprise added much to the reputation of the Navy both at home and abroad. Great credit was given and was justly due to Commodore Preble, who directed and first designed it, and to Lieutenant Decatur, who volunteered to execute it and to whose coolness, self-possession, resources, and intrepidity its success was in an eminent degree due.” Even America’s adversaries admired Decatur’s work with Lord Horatio Nelson, one of the greatest naval commanders in history, calling it “the most bold and daring act of the age.”

Next week, we will discuss William Eaton’s invasion of Tripoli. Until then, may your motto be “Ducit Amor Patriae,” love of country leads me.

When the Democratic-Republicans came to power in the election of 1800, the Jefferson administration effectively shut down and disbanded both the United States Army and Navy. As a result, when American merchant ships were abused and seized as contraband of war on the high seas and in British and French ports during the Napoleonic wars, the United States was helpless to respond.