Road to War, Part 2: The Chesapeake-Leopard Affair

One of the most prominent grievances that led the United States to declare war on Great Britain in 1812 was the impressment of sailors serving on American merchant ships by the Royal Navy. Although this practice continued until after the Napoleonic wars ended in 1815, it truly reached its ugly climax in the summer of 1807 with the infamous Chesapeake-Leopard affair, a naval encounter that brought the two countries to the brink of war.

On June 22, 1807, a British squadron was lying just within the capes of Chesapeake Bay watching for French frigates that had taken refuge at Annapolis. Often these British ships would lay in Hampton Roads or come to the Gosport Shipyard in Norfolk for necessary repairs and, when in port, many British sailors deserted from Royal Navy ships. On March 7, most of the crew from the British sloop Halifax escaped to Norfolk in the ship’s jolly boat. The commander of the Halifax was informed that several men, including an Englishman named Jenkin Ratford, had signed on with the United States frigate Chesapeake, commanded by Captain James Barron, then preparing to sail to the Mediterranean. The Halifax commander appealed to Captain Stephen Decatur, commander of the Gosport Shipyard, to have these sailors returned to British custody, but could not get a redress of his grievances. About the same time, three deserters from the British frigate Melampus also enlisted with the Chesapeake but these deserters were later proven to be native born Americans.

The commander of the British fleet in North American waters was Admiral George Berkeley, based in Halifax. Frustrated at the repeated desertions, Admiral Berkeley sent word via the British frigate Leopard, commanded by Captain Salusbury Humphreys, to the British squadron in the Chesapeake Bay to detain and search the Chesapeake for deserters. The Leopard arrived on station and, after discussing next steps with other ship commanders, Captain Humphreys decided to sail out and await the Chesapeake. On the morning of June 22, the Chesapeake, with a crew of 375 men, got underway and, as no hostilities were anticipated, the Chesapeake sailed with its gun decks still strewn with cables and lumber and several of the guns not yet mounted to their carriages, with Captain Barron planning to square away the ship while at sea.

“Captain James Barron, U.S. Navy (1769-1851).” Naval History and Heritage Command.

Officers on the Chesapeake noticed the Leopard was tracking them on a parallel course but gave it little thought. By midafternoon, both ships were roughly ten miles east of Cape Henry when the Leopard approached within hailing distance and announced that she had dispatches for Barron and requested permission to send them on board. Trading dispatches at sea between warships from different nations during peacetime was common practice and permission was granted.

Around 4pm, Lieutenant Meade from the Leopard came on board and delivered a message declaring that Captain Humphreys believed there were deserters on board the Chesapeake and requesting permission to inspect the crew. This was a highly unusual request as by international protocol naval vessels were considered extensions of a country’s dominion and its sovereignty was to be respected. Consequently, Captain Barron sent Lieutenant Meade back with a note denying Captain Humphreys’ request. After Meade returned to the Leopard, the officers on the Chesapeake began to worry that something was afoot, but not wanting to initiate an aggressive act, Captain Barron did not call the crew to quarters.

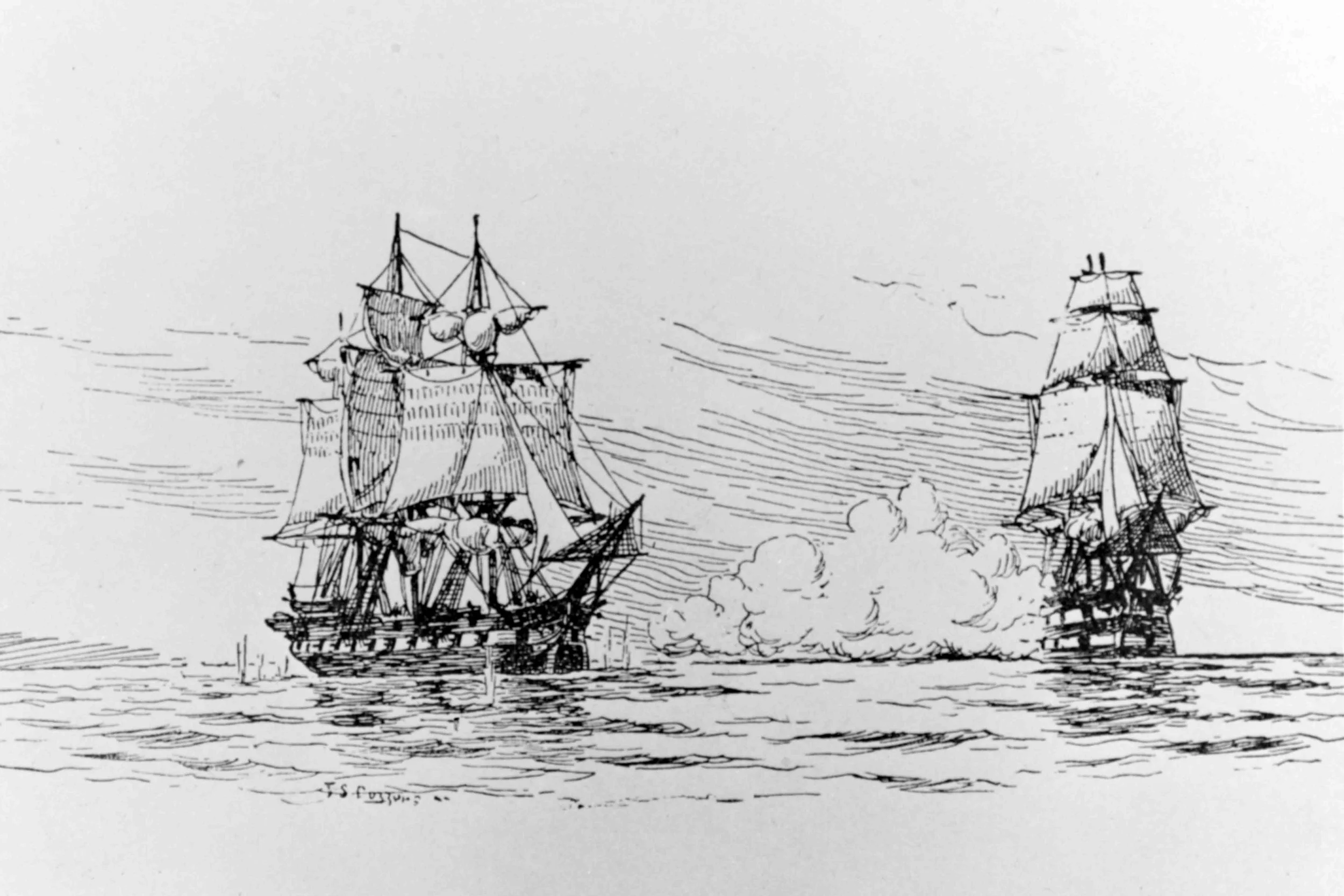

Captain Humphreys hailed Captain Barron one last time asking him to reconsider and then had two warning shots fired across the bow of the Chesapeake. Barron now gave the order to the crew to prepare for battle, a process that would take at least half an hour under the best of conditions as his ship was far from that with its cluttered gun deck. Two minutes later, the Leopard poured a full broadside of solid shot and canister at point blank range into the helpless American frigate. Two more broadsides from the Leopard followed in quick succession without a response from the Chesapeake as there were no lighted matches with which to discharge the guns.

Barron was wounded in the first exchange but remained at his station and, after enduring this massacre for fifteen minutes during which the Americans suffered twenty- one casualties including three killed, ordered his flag to be struck. Shortly before the flag was lowered, a single gun was fired by Third Lieutenant Allen, who brought a live coal with his fingers from the galley just so that it could be claimed that at least one shot had been fired at the Leopard. Several officers from the Leopard came on board to search the crew and took off four deserters, including Jenkin Ratford, and three naturalized Americans. Barron offered his sword and the ship to Humphreys, but the British Captain declined saying it was not his interest to capture the ship but rather to only take off deserters. Embarrassed and disgraced, the Chesapeake returned to Hampton Roads that evening to repair the ship and await further orders.

In January 1808, Captain Barron faced a court martial board whose judges included Captain John Rodgers as President and Captain Stephen Decatur, who held strong opinions against Barron’s conduct and expressed them strongly both inside and outside the courtroom. The court martial declared Barron guilty of being unprepared for battle and suspended him from service for five years without pay or emoluments. This ugly episode reached its final conclusion more than a decade later when on March 22, 1820, Barron killed Decatur, at the time America’s greatest hero, in a duel to avenge his honor.

Anger about British arrogance was deeply felt across the country and, perhaps more than any other event since its founding, the Chesapeake-Leopard affair created a feeling of true national emotion. While most previous events had been partisan in nature, the outrage over this affair brought Americans together as only great crises will and, at least for a time in 1807, the people were no longer Federalists and Democratic-Republicans, but rather Americans.

More importantly, the Chesapeake-Leopard affair demonstrated to President Thomas Jefferson how close the country was to drifting into an unwanted war against England. And as a result, the President took a drastic step that inadvertently caused one of the worst economic disasters in United States history.

Next week, we will discuss the Embargo of 1807. Until then, may your motto be “Ducit Amor Patriae,” love of country leads me.

When the Democratic-Republicans came to power in the election of 1800, the Jefferson administration effectively shut down and disbanded both the United States Army and Navy. As a result, when American merchant ships were abused and seized as contraband of war on the high seas and in British and French ports during the Napoleonic wars, the United States was helpless to respond.