The Barbary Wars, Part 4: To the Shores of Tripoli

William Eaton led the first successful invasion of a foreign land by the United States when in 1804 he led a handful of Marines and a hodgepodge assembly of Christian mercenaries and unruly Arabs to conquer the Tripolitan port city of Derne. It was a momentous act, one that hastened the end of the first Barbary war and informed the world that the United States would not tolerate any tyranny over its affairs.

Eaton, forty years old at the time, was born on February 23, 1764, in Woodstock, Connecticut to a farmer with thirteen children. In 1780, Eaton ran away from home to join the Continental Army, serving until 1783 and attaining the rank of Sergeant. After the war, Eaton taught school to earn money for college and, in 1790, graduated from Dartmouth College. Two years later, Eaton accepted a Captain’s commission in the Legion of the United States, in which he served until he was appointed the Consul to Tunis in 1797. In 1803, following years of increasing belligerency by the Dey of Tunis and his demands for higher tribute payments which Eaton refused to pass on to Washington, Eaton left for home.

But while in Tunis, Eaton had met Hamet Karamanli, the exiled Pasha of neighboring Tripoli, whose younger brother Yusuf had ousted Hamet from the throne in 1796. After Yusuf declared war on the United States in 1801, Eaton hatched a plan to strike back. That plan was to invade Tripoli and free the American sailors from the USS Philadelphia being held captive, and defeat and oust Yusuf, replacing him with Hamet; thereby, successfully ending the war and installing a friend on the throne of Tripoli.

Back in Washington, Eaton shared his scheme with President Thomas Jefferson and Secretary of State James Madison. Jefferson, who detested the idea of paying tribute to the Barbary pirates, supported and approved the plan, but insisted that no written authorization be given; this was to be a “secret” mission, the first overseas covert operation in the country’s history. On May 26, 1804, after meeting with his cabinet, the President named Eaton a “Navy Agent for the Several Barbary Regencies” with orders to report to the Commodore Samuel Barron of the Mediterranean fleet.

Charles Balthazar Julien Févret de Saint-Mémin. “William Eaton.” National Portrait Gallery.

Upon arriving in the Mediterranean and learning Hamet was in Egypt, Eaton proceeded there in early December 1804 in the USS Argus, commanded by Captain Issac Hull, the future naval hero of the War of 1812. But Hamet was not an easy man to pin down and it was not until February 1805 that Eaton and Hamet met up in Alexandria. Finally, on March 3, they began their 400-mile march to Derne, an important Tripolitan seaport five hundred miles east of the capital city of Tripoli. The army, if you can call it that, consisted of Eaton, now styling himself General Eaton, two U.S. midshipmen, George Washington Mann and Pascal Paoli Peck, U.S. Marine Lieutenant Presley O’Bannon and seven Marines under his command, seventy-five Christian mercenaries of various nationalities (Greek, Italian, French), and roughly four hundred Arab Moslems.

The march, which hugged the Mediterranean coastline, proved to be one of the more arduous and challenging treks made by an American force. Between scanty provisions, lack of water, and the constant squabbling of the Arabs, Eaton was driven to his wits end. Midshipman Peck later wrote, “Certainly it was one of the most extraordinary expeditions ever set on foot. We were very frequently 24 hours without water, and once 47 hours without a drop. Our horses were sometimes 3 days without, and for the last 20 days had nothing to eat, except what they picked out of the sand.” But at last, through Eaton’s steady leadership and the steadfast perseverance of O’Bannon and his U.S. Marines, after fifty-four days, the army arrived on the outskirts of Derne on the afternoon of April 25, 1805.

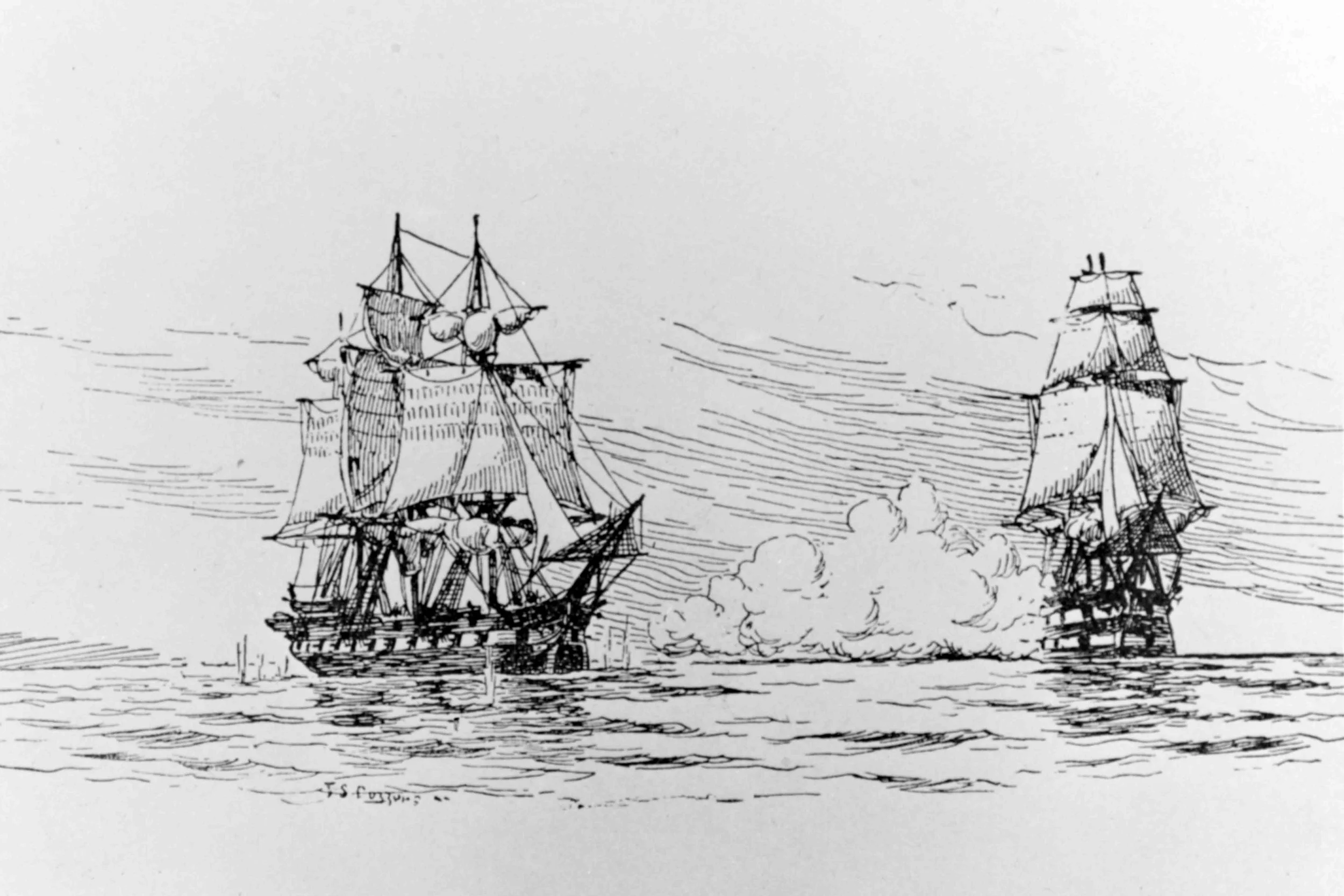

Eaton sent a message into the city asking the people to surrender the town rather than waste lives on a hopeless cause, to which the Governor of Derne quickly responded “My head or yours.” Taking that as a “no,” Eaton launched his attack on April 27, while three ships from the Mediterranean squadron, Argus, 18 guns, Hornet, 10 guns, and Nautilus, 14 guns, fired on the town from the harbor. Because of constant bickering between the Moslems and the European Christian mercenaries, Eaton gave them separate missions and kept the Christians with his attack force which numbered about one hundred men including the Marines under Lieutenant O’Bannon; the town held roughly 1,000 well-armed defenders.

After about an hour of inconclusive musketry, Eaton and O’Bannon led their men in a headlong bayonet charge against the city walls which scattered the defenders. As Captain Hull, who was observing the fight through his spyglass from the deck of the Argus, later wrote, “At about half past 3, we had the satisfaction to see Lieutenant O’Bannon and Mr. Mann, midshipman of the Argus, with a few brave fellows with them, enter the fort, hall down the Enemy’s flag, and plant the American ensign on the walls of the Battery.” For the first time ever, the American flag, now consisting of fifteen stars and stripes, had been planted in battle on foreign soil outside North America. Hamet’s force of nearly 1,000 Arabs did not join the attack, observing from a safe distance and only approaching the town after the Americans had secured it.

In early May, a 1,200-man Tripolitan relief force arrived and attacked several times over the next month, but Eaton’s force held strong. Then, on June 11, Eaton was informed by Commodore Barron that peace had been concluded with Yusuf Karamanli, leaving Yusuf on the throne after he agreed to immediately release all American prisoners and end all tribute payments from the United States. The news was bittersweet for Eaton who felt the United States had abandoned Hamet and his followers when they were on the cusp of victory. But Eaton was proud that his actions, along with those of Lieutenant O’Bannon and a contingent of U.S. Marines, had led to the release of all American prisoners and had carried the Stars and Stripes to the shores of Tripoli.

Next week, we will discuss the conclusion of the Barbary Wars. Until then, may your motto be “Ducit Amor Patriae,” love of country leads me.

When the Democratic-Republicans came to power in the election of 1800, the Jefferson administration effectively shut down and disbanded both the United States Army and Navy. As a result, when American merchant ships were abused and seized as contraband of war on the high seas and in British and French ports during the Napoleonic wars, the United States was helpless to respond.