Road to War, Part 1: The Causes of the War of 1812

Many people have called the War of 1812 the “second American Revolution,” and while that phrase has some merit, the facts do not fully support the assertion. It is true that in both cases America’s enemy was Great Britain and the main catalyst that took us to war was American animosity resulting from perceived British wrongs, but the similarities essentially end there. This second fight between the United States and her former Mother Country was largely an unintended and undesired consequence of the almost continuous war that raged from 1793 to 1815 between France and Great Britain. Virtually everything Great Britain did during this era was geared towards defeating France, and the oppressive measures the British placed on American commerce and merchantmen that led to the War of 1812 had everything to do with driving Napoleon from power and nothing to do with reasserting colonial era authority over the United States.

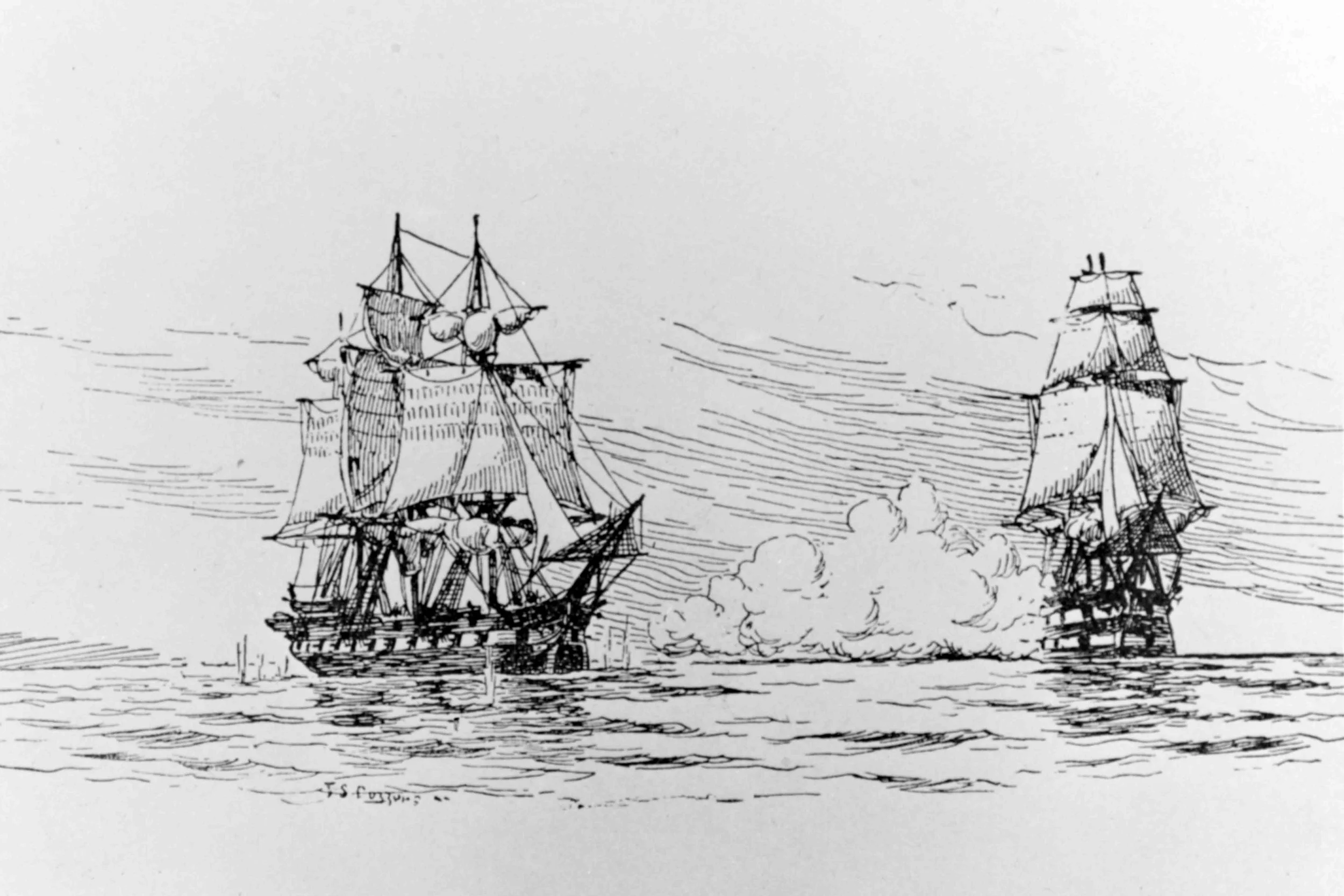

After Admiral Horatio Nelson destroyed the combined French and Spanish fleets at Trafalgar on October 21, 1805, the Royal Navy became the unquestioned master of the high seas and bottled up the French merchant fleet. Consequently, American ships became the primary conduit to bring trade goods to France, especially from her numerous colonial possessions. To shut down this economic lifeline and bring Napoleon to the peace table, Great Britain issued a series of measures that adversely affected American merchantmen.

The first such ruling, known as the Essex case, was issued in 1805 by the British High Court of Admiralty and centered on the American merchant ship Essex, which was seized by British ships and taken into port as a prize of war. The High Court, whose purpose was to rule on the disposition of all captured vessels, declared that the Essex was a true prize of war even though it was a ship from a neutral nation. The justification used by the High Court was the so-called Rule of 1756, first invoked during the French and Indian War, which basically stated trade not allowed during peacetime was not allowed during war. Since neither France nor Great Britain allowed ships from neutral nations to carry goods from their colonies to Europe during peace, they could not do so during war. This ruling opened the floodgates for the seizures of American ships by both French and British privateers and, in the decade that followed, over 1,500 American ships were taken as prizes. And because Presidents Jefferson and Madison believed defense spending was wasteful, especially naval expenses, they refused to build up the warships required to protect the American merchant fleet.

“Horatio Nelson.” National Maritime Museum via Wikimedia.

To further tighten the trading noose around France, Great Britain issued a series of edicts known as Orders in Council, legally binding decrees by the British Privy Council, a sort of board of advisors to the King. The first Order was issued on May 16, 1806, and declared a blockade of all European ports from the Elbe River in the north to Brest in the south. Napoleon responded with his Berlin Decree on November 21, which proclaimed that “the British Isles are declared to be in a state of blockade” and forbid all nations, including neutrals like the United States and allies like Spain and Russia, to trade in British ports. Moreover, the Emperor immediately seized all American ships in French ports, declaring them prizes of war.

However, since Napoleon had lost his fleet at Trafalgar the previous year, Napoleon’s blockade of the British Isles was unenforceable and no more than a “paper blockade.” The following year, after two more retaliatory British Orders in Council extended the trade restrictions with France, Napoleon issued his Milan Decree on December 17, 1807, which extended his trade restrictions against Great Britain. Taken together, Napoleon’s Berlin and Milan Decrees created an economic embargo against the British that came to be known as the Continental System.

Unfortunately for Napoleon, this system ultimately led to his demise as the French economy suffered more from the trade restrictions than did Great Britain, who controlled the high seas and soon found new markets in places like South America. Of more importance, Napoleon’s Continental System turned allies into enemies as countries chaffed under his trade restrictions that harmed their economies. This discontent eventually led to a Spanish revolt and the Peninsular War that lasted from 1808 to 1814, and to Russia’s refusal to participate in the Continental System, which precipitated Napoleon’s disastrous invasion of Russia in 1812.

As part of their maritime strategy, British warships patrolled the North American coast and, consequently, it was common for these vessels to use American ports to resupply their provisions and perform minor repairs. But it also was common for British seamen when in port to desert and sign on with an American merchant ship that typically offered higher pay and better conditions than the Royal Navy. In fact, it is estimated as many as 9,000 former Royal Navy seaman served on American merchant ships.

To counter this loss and to man the growing fleet required to enforce its blockade of French controlled ports, the Royal Navy began to forcefully conscript British citizens to fill the ranks. This practice, known as impressment, was carried out both on land with “press gangs” that scoured British seaside towns looking for experienced sailors, and on the sea by Royal Navy cruisers, who took British born men from both British and American merchant ships. Although many American ship captains issued “official” citizenship papers to British deserters that established them as naturalized Americans, Great Britain did not recognize the certificates, declaring that anyone born a British citizen remained a British citizen. Consequently, many “Americans” were pressed into the Royal Navy. Impressment reached its apex during the Napoleonic Wars when the Royal Navy increased by over 40,000 sailors, and, astonishingly, it is estimated that by 1805 roughly half the Royal Navy's 120,000 sailors were “pressed” men.

But the most egregious violation of American neutrality rights occurred in the summer of 1807 and led the United States and Great Britain to the brink of war.

Next week, we will discuss the Chesapeake-Leopard incident. Until then, may your motto be “Ducit Amor Patriae,” love of country leads me.

When the Democratic-Republicans came to power in the election of 1800, the Jefferson administration effectively shut down and disbanded both the United States Army and Navy. As a result, when American merchant ships were abused and seized as contraband of war on the high seas and in British and French ports during the Napoleonic wars, the United States was helpless to respond.