American Judiciary, Part 11: The Legacy of John Marshall

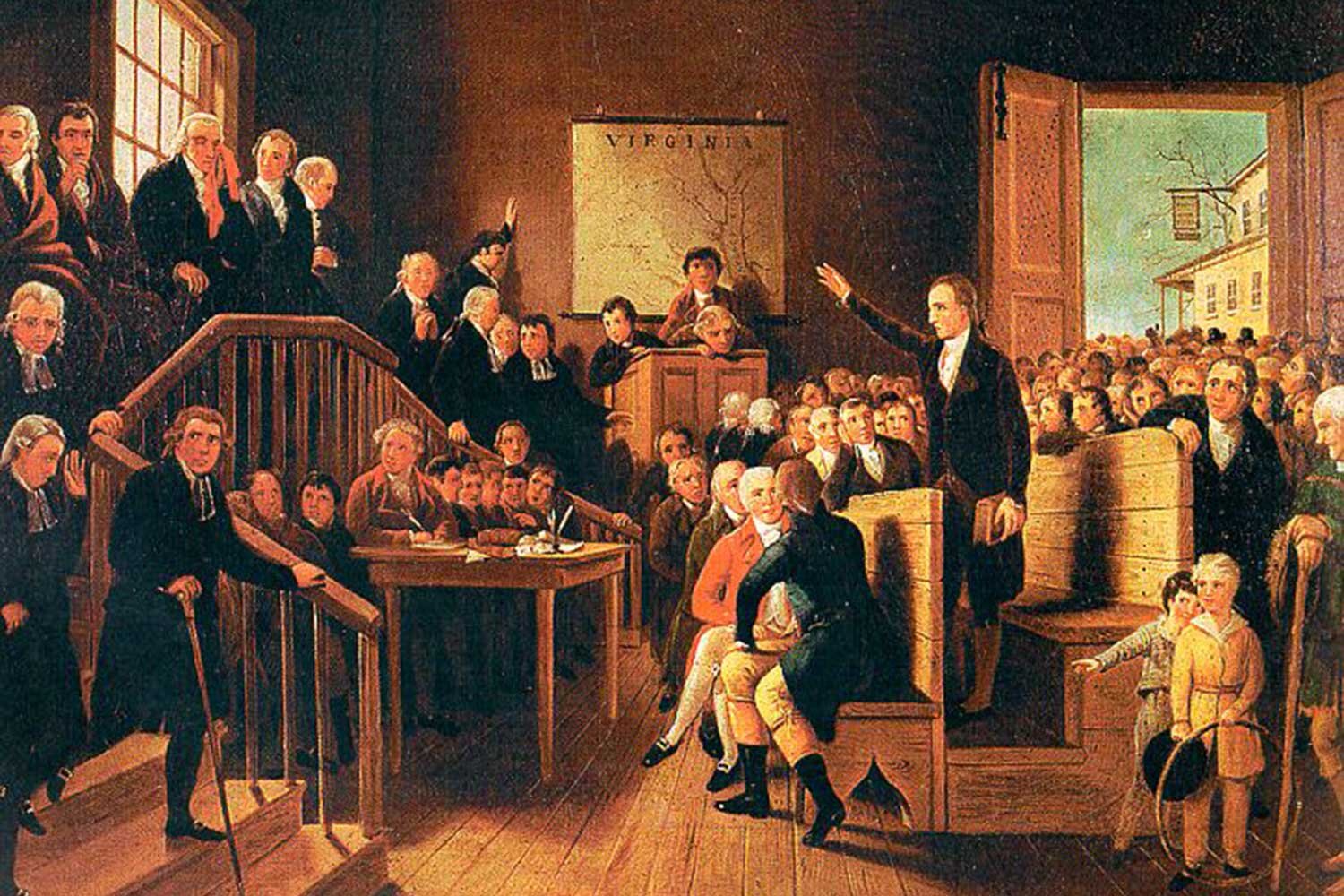

The first few decades of the 19th century were an exciting time for the American judiciary, at least as exciting as anything involving attorneys and judges can be. From the time Thomas Jefferson was sworn in as President on March 4, 1801, through the presidency of Andrew Jackson, there was a tremendous antagonism between the populist Executive branch and the Supreme Court, the last bastion of Federalism. This unprecedented tension between the Executive and the Judiciary made for frequent and intense conflicts, arguably more frequent and more intense than during any other period in our country’s history.

The man at the center of this cauldron of strife was John Marshall who was appointed as the fourth Chief Justice of the Supreme Court on February 4, 1801, by President John Adams. And over three and a half decades in that role, Marshall proved to be the right man at the right moment in history for this position that was seemingly created just for him. From that seat of elevated justice, Marshall oversaw the creation of the American judiciary, a legal system that is unrivaled in the world, and taught the nation that the Constitution is the supreme law of the land and that it is the responsibility of the courts to interpret the law.

During his time as Chief Justice, Marshall established and solidified many concepts of American jurisprudence, and key rulings issued by the Marshall Court established precedents that have helped guide the country’s legal pathway for over two centuries. More than anything, the consolidated effect of these rulings was to confirm the long-held Federalist position that the Constitution trumps all legislation, both state and federal, and that the national government is paramount over the states, a theory that directly conflicted with states’ rights advocates like Thomas Jefferson, thus creating the constant rub between the two American icons.

By 1811, Democratic-Republican appointees on the Supreme Court outnumbered Federalist appointees five to two. Despite being in the ideological minority, Marshall's power of persuasion and ability to identify the core elements of every issue brought others around to his point of view. As Oliver Walcott observed, Marshall had the knack of “putting his own ideas into the minds of others, unconsciously to them.” But Marshall was wise enough to recognize that consensus in major decisions was critical and, consequently, often modified his position to achieve that consensus with his colleagues.

“Thomas Jefferson.” The White House Historical Association via Wikimedia.

In 1803, the landmark case of Marbury v Madison established that it was the exclusive province and duty of the judiciary to interpret the law, a concept known as judicial review. As the Chief Justice asserted, “It is emphatically the province and duty of the judicial department to say what the law is.” By enshrining this concept, Marshall created a healthy conflict between the co-equal branches and installed a check on legislative overreach.

In the 1810 case of Fletcher v Peck, Marshall ruled that the state of Georgia must adhere to the Constitution’s Contract Clause the same as the federal government and, for the first time, voided a state law, further establishing the supremacy of the federal judiciary.

In 1816, Marshall affirmed in McCulloch v Maryland that the federal government has both enumerated and implied powers under the Constitution, a ruling that broadly expanded the powers of the federal government. This case established that although the government was bound by timeless written principles, implied powers were necessary to give it the flexibility “to be adapted to the various crises of human affairs.” Marshall declared “Let the end be legitimate, let it be within the scope of the Constitution, and all means which are appropriate, which are plainly adapted to that end, which are not prohibited but consistent with the letter and the spirit of the Constitution, are constitutional.”

Also in 1816, in the case of Martin v Hunter’s Lessee, Marshall declared that the Supreme Court had the power to hear appeals from state courts where a federal issue was involved. This ruling established the precedent that federal courts were the final arbiters in all cases dealing with federal law.

In Dartmouth v Woodward in 1819, Marshall’s opinion extended the protections of the Constitution’s Contract Clause to private corporations with Marshall declaring that the sanctity of a contract is essential to the functioning of a republic, and these rights were guaranteed to both individuals and corporations. This expansion of Marshall’s earlier ruling in Fletcher further enshrined private property rights and gave corporations confidence that their investments would be protected.

In the Gibbons v Ogden case of 1824, Marshall declared that the regulation and control of interstate commerce was vested in Congress and furthermore that interstate navigation was a form of commerce and thus could be regulated as well by Congress. This decision dealt a blow to state monopolies and opened domestic markets to competition and growth.

In 1832, Marshall and President Andrew Jackson came to grips over the case of Worcester v Georgia, in which the Marshall Court established that the federal government had exclusive dominion in dealing with Indian nations and voided a Georgia statute. As a result, Marshall ordered Georgia to free two prisoners, one of whom was Samuel Worcester, but Georgia refused to follow this directive. President Jackson declined to assist the Court in enforcing the decision, pointedly demonstrating that the Supreme Court was somewhat powerless without Executive action.

John Marshall gave much of his life to the country he adored and is arguably the most influential man in American history who was never elected President. In an indication of Marshall’s devotion to his country, he not only served in the Continental Army (1775-81) and as a diplomat to France (1797-98), but is also one of just a handful of men in our nation’s history who have served in all three branches of government, the legislative as a United States Representative from Virginia (1799-1800), the executive as President John Adams’ Secretary of State (1800-01), and, of course, the judicial as Chief Justice of the Supreme Court (1801-35).

John Adams, who appointed Marshall as Chief Justice in one of his final acts as President, stated, “my gift of John Marshall to the people of the United States was the proudest act of my life.” Pretty high praise.

Next week, we will discuss the background of the War of 1812. Until then, may your motto be “Ducit Amor Patriae,” love of country leads me.

The first few decades of the 19th century were an exciting time for the American judiciary, at least as exciting as anything involving attorneys and judges can be. From the time Thomas Jefferson was sworn in as President on March 4, 1801, through the presidency of Andrew Jackson, there was a tremendous antagonism between the populist Executive branch and the Supreme Court, the last bastion of Federalism. This unprecedented tension between the Executive and the Judiciary made for frequent and intense conflicts, arguably more frequent and more intense than during any other period in our country’s history.