American Judiciary, Part 7: Marbury v. Madison

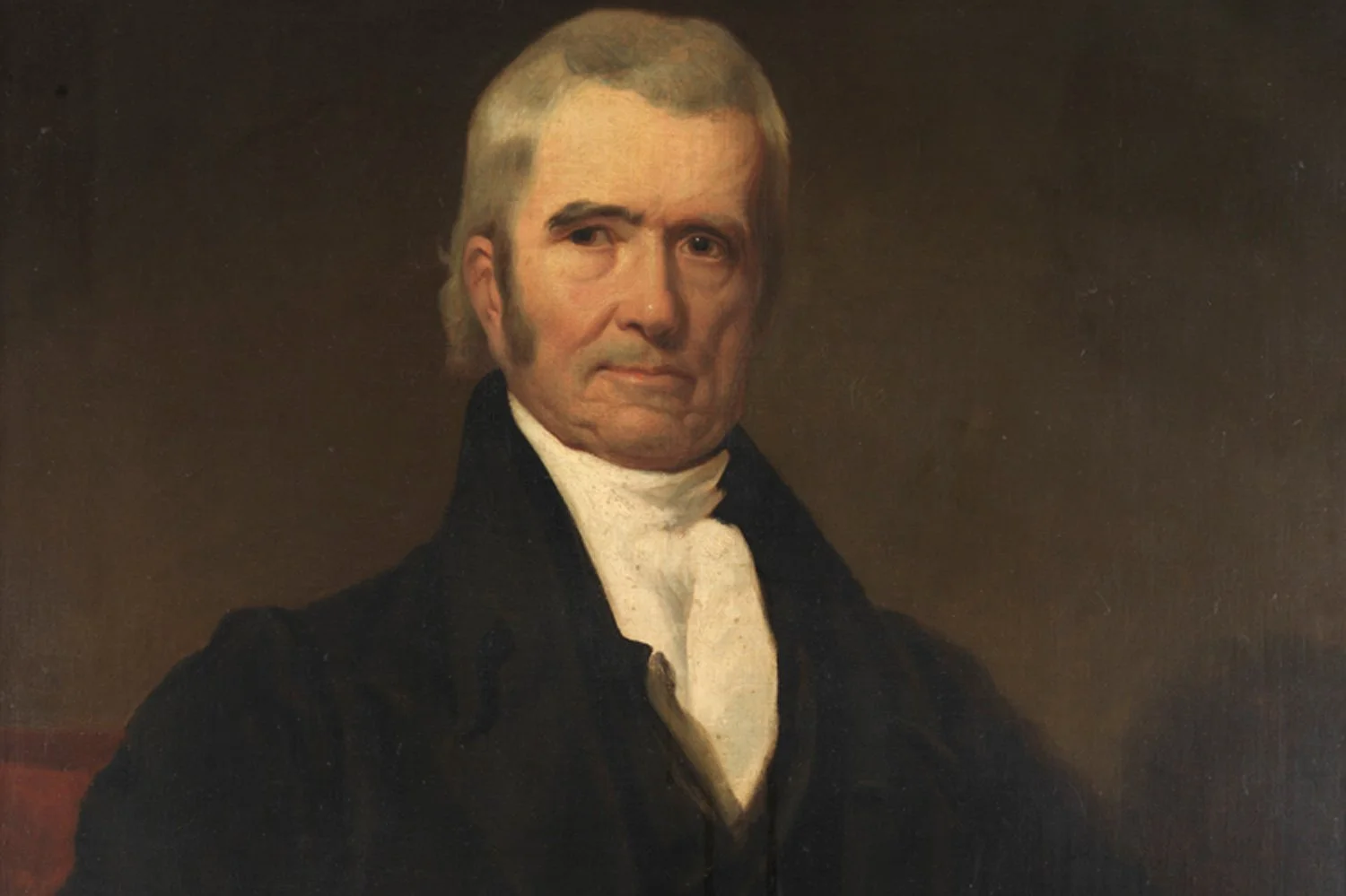

Marbury v Madison is the most consequential legal decision in our nation’s history because it established the concept of judicial review in the United States. This principal grants to the judiciary the responsibility to review laws for their constitutionality and gives it the power to void legislation it finds repugnant to the Constitution. That decision was rendered by John Marshall, Chief Justice of the Supreme Court in 1803, but the road to that decision extends further back.

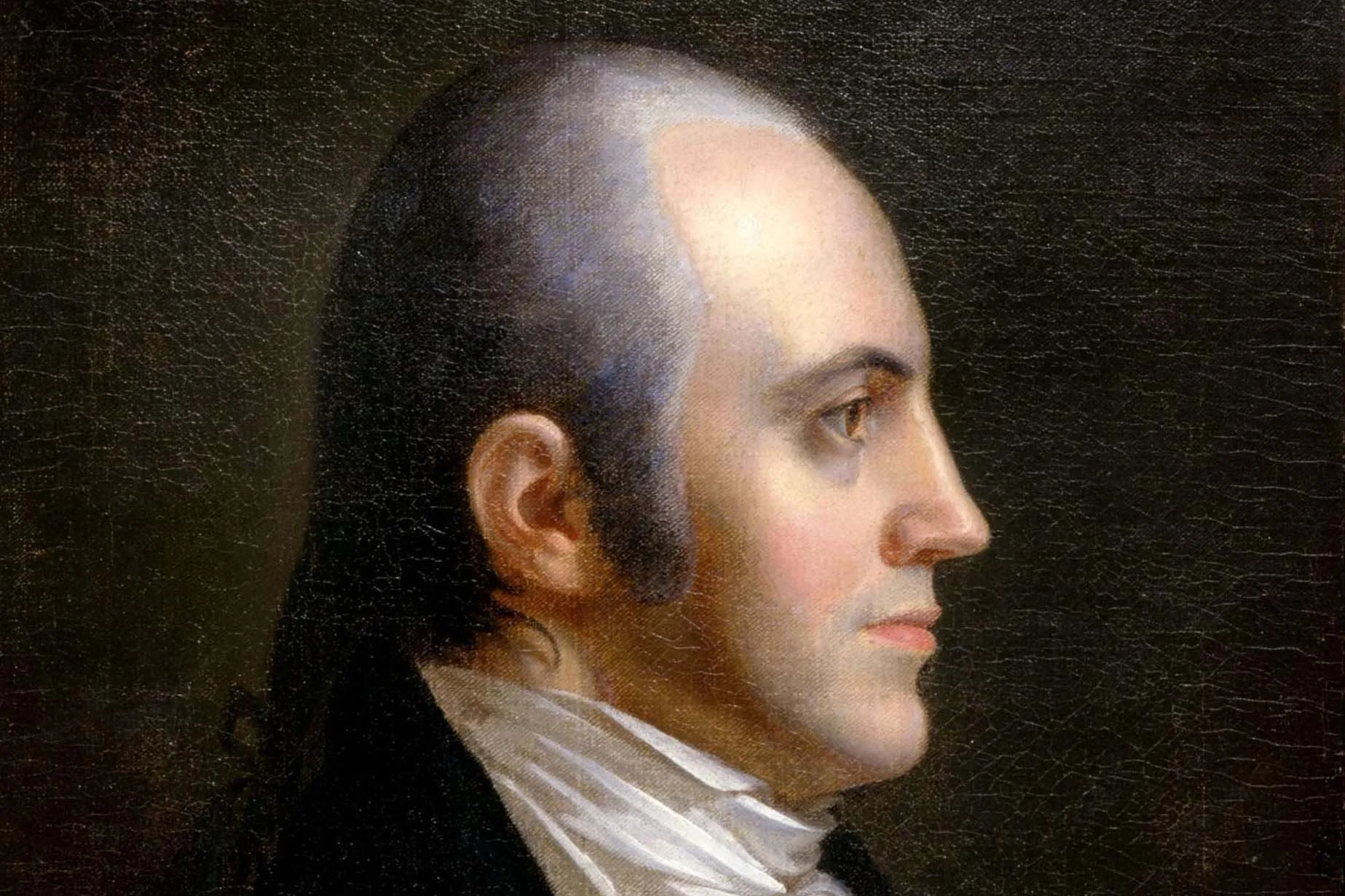

To squash criticism from Democratic-Republican newspapers, Congress passed the Sedition Act in July 1798, a law which made it illegal to criticize the Adams administration, a clear violation of the First Amendment guarantees of freedom of the press and of speech. Vice President Thomas Jefferson crafted a response and asked his protégé, James Madison, to do likewise. Known to history as the Kentucky and Virginia Resolutions, they declared that states could ignore a federal law if, in a state’s opinion, that law violated the Constitution. Jefferson’s theory was a clear assertion of states’ rights and a challenge to the concept that the laws of the national government were paramount to those of the states.

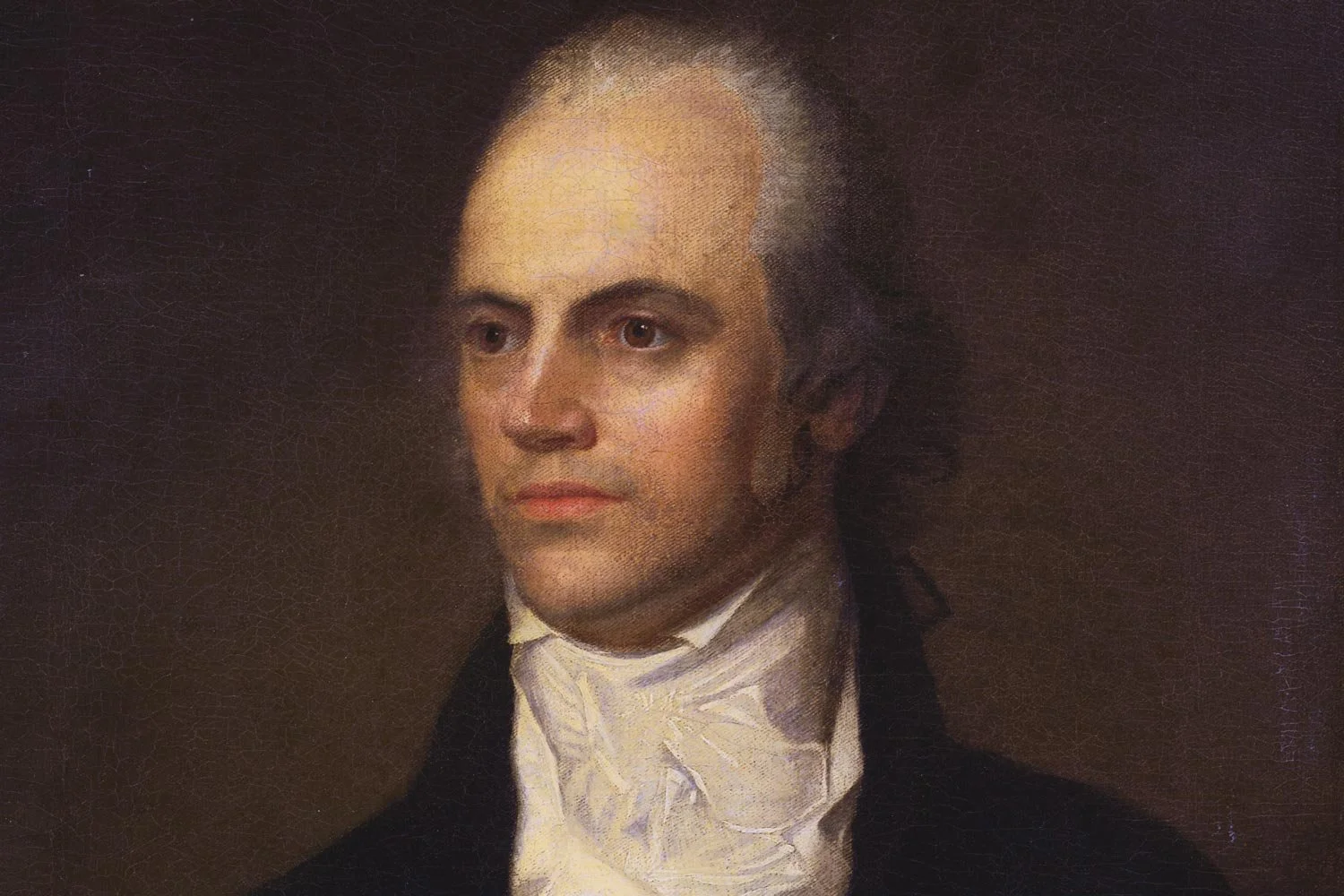

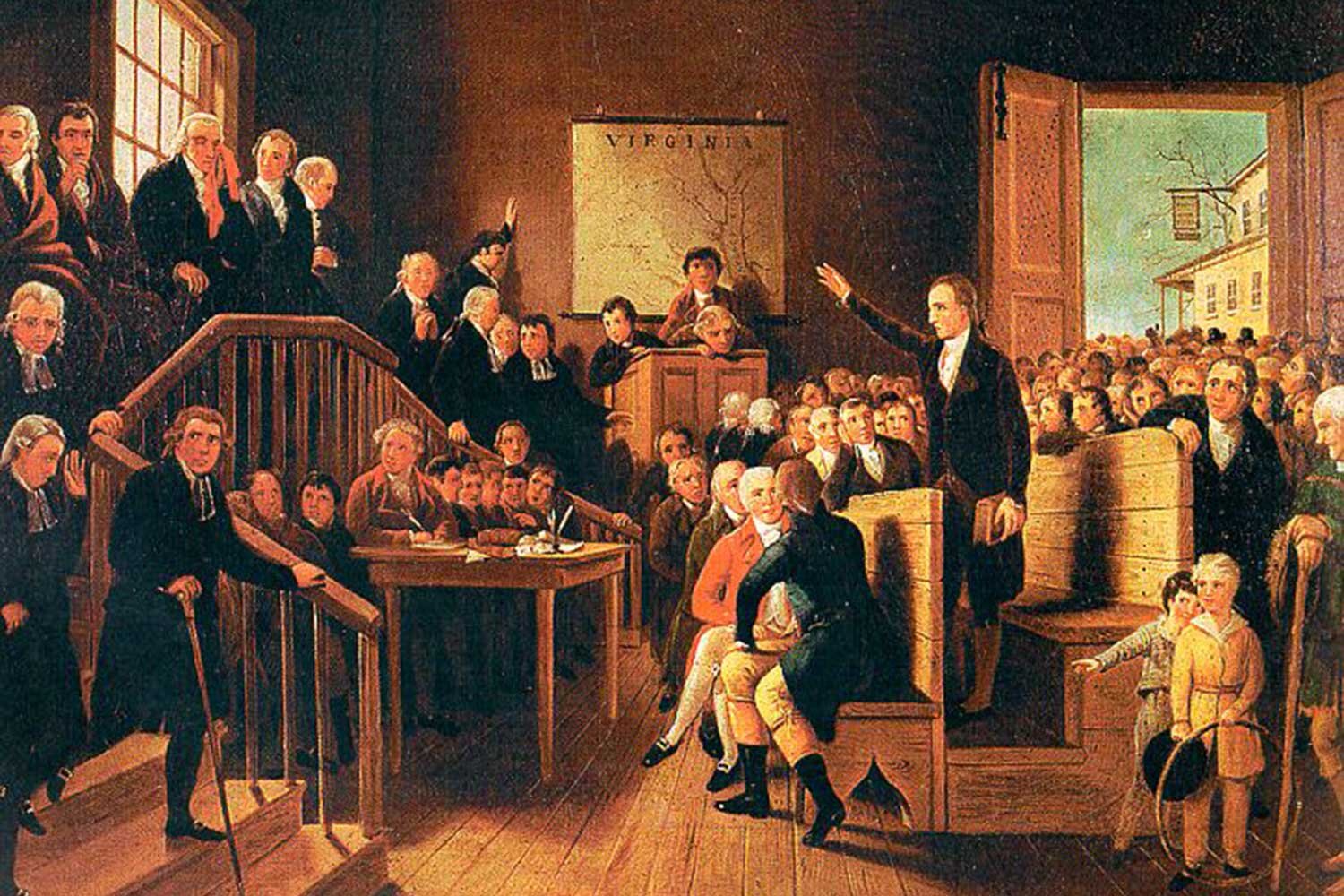

Two years later, when the political winds shifted and Jefferson’s Democratic-Republican party swept into office in the election of 1800, Federalists like John Marshall grew concerned that Jefferson’s states’ rights theories would continue to gain traction. If that happened, it was likely the Constitution would no longer be the supreme law of the land and that the national government would become powerless like that under the Articles of Confederation. Marshall knew he had to find a way to restore the authority of the Constitution, and that opportunity soon presented itself.

In February 1801, the Federalist controlled Congress had passed the Judiciary Act of 1801 which strengthened the federal judiciary, in part by expanding the number of judgeships and justice of the peace positions. On March 2, two days before leaving office, Adams submitted a list of fifty-eight names, all Federalists, to fill these new positions. The next day, Congress approved the names en masse and, accordingly, Adams signed the commissions (critics argued he did so until midnight on his last day in office, thus branding these appointees as the “midnight judges”) and asked then Secretary of State John Marshall to deliver the commissions.

Marshall delivered most but not all the commissions before the Jefferson administration was sworn in at noon on March 4. The new President directed his Secretary of State, James Madison, to withhold the remaining commissions, one of which was a Washington County justice of the peace position for William Marbury, a Maryland businessman and staunch Federalist. Consequently, Marbury sued requesting the Supreme Court issue a writ of mandamus (which is a court order compelling a government official to perform a legally appointed task) forcing Madison to deliver his commission and arguing that the Supreme Court had been granted that authority by Section 13 of the Judiciary Act of 1789.

“Judiciary Act of 1789.” Wikimedia.

The case was heard by the Supreme Court and, on February 24, 1803, Marshall issued his landmark ruling. Marshall stated the case boiled down to three questions. First, was Marbury’s commission valid? The answer was yes; it had been approved by Congress and signed by the President. The fact that the commission had not been delivered did not matter as the delivery of the commission was simply a convenience. Once the commission had been approved by Congress and signed by the President, it became valid. The Chief Justice pointedly used this opportunity to remind the President and Secretary of State that they were not above the law and must perform duties required by the office they held.

Second, recognizing that the commission was valid, the next question to decide was did Marbury have a legal remedy? The answer again was yes as Marshall stated, “The very essence of civil liberty certainly consists in the right of every individual to claim the protection of the laws, whenever he receives an injury. One of the first duties of government is to afford that protection.”

The third and final question for the Supreme Court to answer was whether the Supreme Court was the right venue for issuing that writ of mandamus and here Marshall surprised everyone. The Chief Justice stated the Supreme Court was not the proper venue because Section 13 the Judiciary Act 1789 was unconstitutional since it granted powers to the Supreme Court (issuing writs of mandamus) not found in the Constitution. As a result, for the first time in Supreme Court history, Marshall declared a law passed by Congress to be unconstitutional and dismissed the suit. On the surface, Marshall’s decision seemed insignificant and a surprising victory for the Democratic-Republicans. But the legal reasoning Marshall went on to further explain staked out his brilliantly considered position on the power of the Court and its role as a co-equal branch in our Constitutional government, and in doing so established the precedent of judicial review, perhaps the most impactful legal doctrine in our nation’s history.

The Chief Justice explained “The powers of the legislature are defined and limited; and that those limits may not be mistaken or forgotten, the constitution is written. To what purpose are powers limited and to what purpose is that limitation committed to writing, if these limits may, at any time, be passed by those intended to be restrained? It is a proposition too plain to be contested, that the Constitution controls any legislative act repugnant to it.”

Marshall goes on to state, “It is emphatically the province and duty of the judicial department to say what the law is.” In this one sentence, John Marshall succinctly encapsulated the essence of judicial review: that the courts have the authority and duty to review acts of the legislature and to declare invalid any that conflict with the Constitution. This concept of an objective review process of legislation by an independent judiciary, free from political control, is uniquely American and this strict adherence to the rule of law is a significant part of American exceptionalism.

With his decision in Marbury v Madison, Marshall had fired a Federalist challenge at the states’ rights theories of Thomas Jefferson and the Democratic-Republicans, and they would not take it lying down.

Next week, we will discuss the impeachment of Justice Samuel Chase. Until then, may your motto be “Ducit Amor Patriae,” love of country leads me.

The first few decades of the 19th century were an exciting time for the American judiciary, at least as exciting as anything involving attorneys and judges can be. From the time Thomas Jefferson was sworn in as President on March 4, 1801, through the presidency of Andrew Jackson, there was a tremendous antagonism between the populist Executive branch and the Supreme Court, the last bastion of Federalism. This unprecedented tension between the Executive and the Judiciary made for frequent and intense conflicts, arguably more frequent and more intense than during any other period in our country’s history.