American Judiciary, Part 10: The Treason Trial of Aaron Burr

Aaron Burr's grand scheme to create his own country, possibly in Mexico or from United States territory, began to collapse late in 1806, practically before it ever got started. This empire in the sky built largely in Burr’s fertile mind was swiftly coming to an end. Upon finding out that President Thomas Jefferson had ordered a warrant be issued for his arrest, Burr led his so-called insurrectionist army, a group of twenty followers including Harman Blennerhassett, one of his main accomplices, down the Ohio to the Mississippi enroute to New Orleans; hoping to salvage whatever he could from his fading dreams of glory.

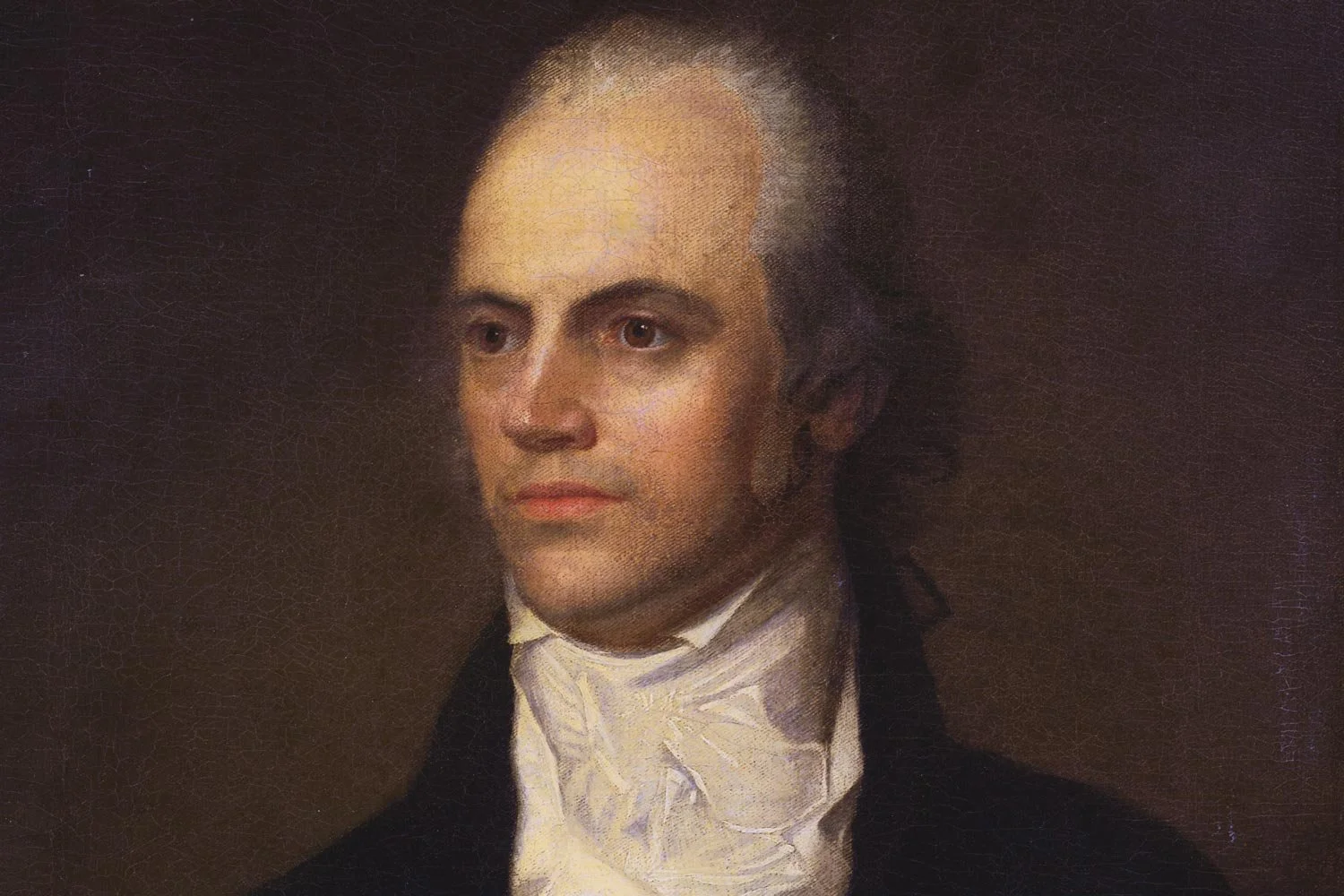

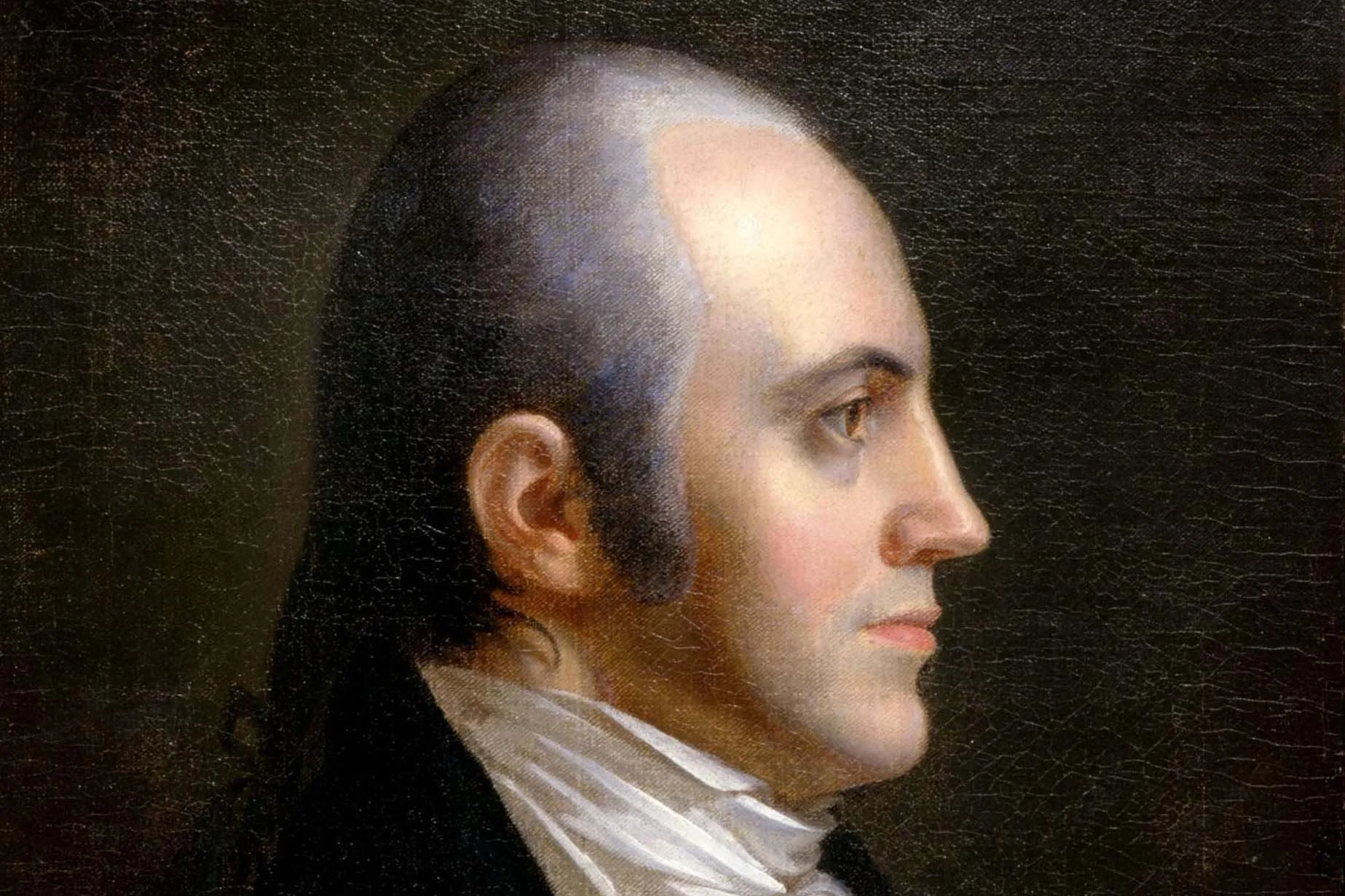

But it began to dawn on Burr as they headed south that he had two choices, neither of which was appealing. He could continue down the Mississippi to New Orleans where he would fall into the hands of General James Wilkinson who had betrayed Burr or turn himself into federal officials and President Jefferson who despised Burr. Not surprisingly, Burr chose neither, opting instead for option number three and, on February 1, 1807, donned a disguise and headed overland toward the Gulf, leaving his accomplices on the flotilla behind to fend for themselves. In late February, Burr was captured about fifty miles north of Mobile and, three weeks later, was sent to Richmond to stand trial for treason against the United States.

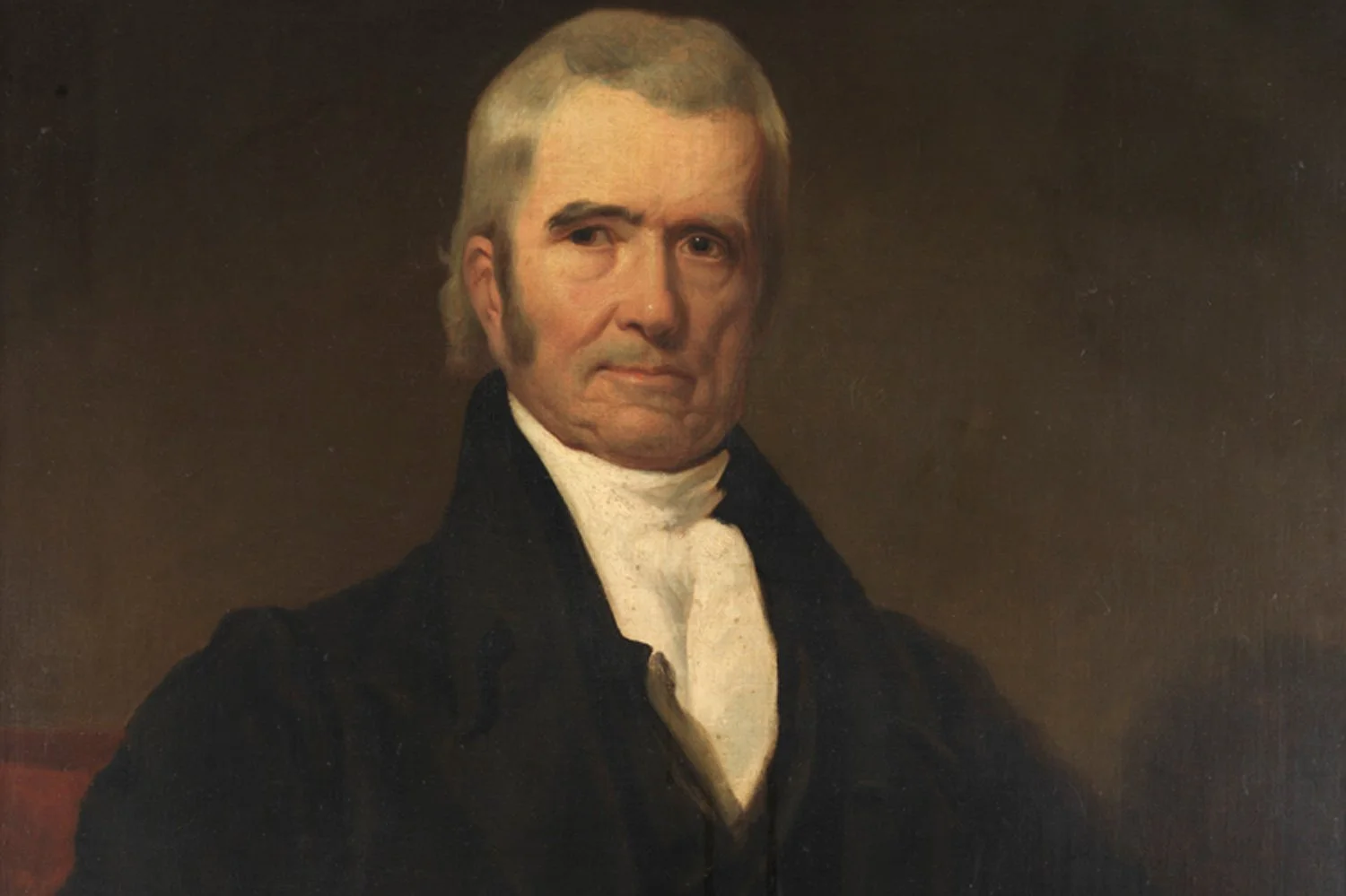

The trial convened in the Virginia capital because Blennerhassett Island where the overt act of treason was alleged to have taken place was within the Richmond district. And, as fate would have it, that district was presided over by Chief Justice John Marshall as part of his Supreme Court circuit riding duties. Thus, either by grand coincidence or Divine intervention, Marshall and Jefferson, two men who despised each other as much as two men ever did, were once again brought into conflict.

“James Wilkinson.” National Portrait Gallery, Smithsonian Institution.

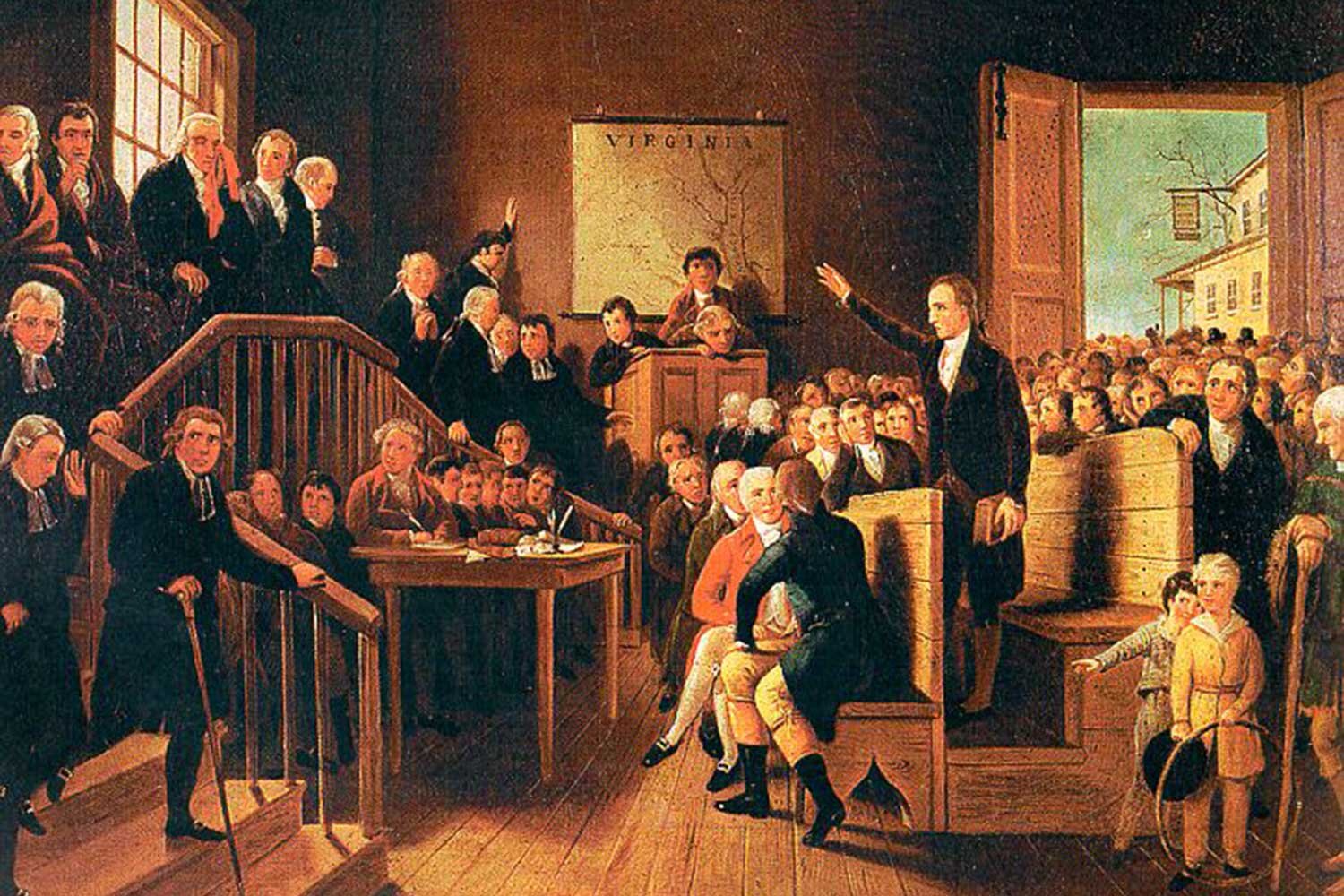

The grand jury convened on May 22, and the defense asked Marshall to subpoena President Jefferson to testify because Burr’s team, perhaps hoping to embarrass the President, insisted Jefferson had information that could help their client. Furthermore, Luther Martin, Burr’s lead attorney, asserted that the President had long known about Burr’s actions but chose to ignore them and Martin wanted to know why. Marshall, while recognizing the delicate nature of issuing a subpoena to the President, felt he had no choice but to issue it stating, “if it be a duty, the court can have no choice in the case.” Jefferson was angry, maybe even shocked, that Marshall would have the nerve to give an order to the President. And in this test of Olympian wills, President Jefferson defied the Chief Justice and refused to comply, arguing the Judiciary and the Executive branches were co-equal and, consequently, the Judiciary could not demand an action of the Executive. The President asked, “Would the Executive be independent of the Judiciary if he were subject to the commands of the latter and to imprisonment for disobedience?”

The star witness for the prosecution, General Wilkinson, finally appeared in court on June 15, but the General proved to be a liability as Wilkinson was forced to admit on the stand that he had altered Burr’s cyphered letter that was the prosecution’s main piece of evidence. Such was the indignation against Wilkinson for his duplicity that he himself just barely escaped being indicted on charges of misprision of treason, the crime of being aware of treasonous activity but not informing officials of it. John Randolph, a leader of the Democratic-Republican party in the House and one of the jurymen, noted that “Wilkinson is the only man that I ever saw who was from the bark to the very core a villain.” Despite Wilkinson’s failure on the witness stand, the grand jury, made up of many of Virginia’s most prominent men, indicted Burr for treason on June 25.

Burr’s trial began in Richmond on August 3 and, after four weeks of testimony, Marshall issued his opinion to the courtroom and the jury, pointing out that according to the Constitution “no person shall be convicted of treason unless on the testimony of two witnesses to the same overt act.” And, as the prosecution had failed to produce evidence and witnesses to an overt act, Burr must be found innocent of the charge. Marshall next gave what seemed to be a direct address to President Jefferson who had criticized Marshall’s handling of the case. “That this court does not usurp power is most true; that this court does not shrink from its duty is not less true. No man is desirous of placing himself in a disagreeable situation; but if he has no choice in the case - if there is no alternative presented to him but a dereliction of duty or the opprobrium of those who are denominated the world - he merits the contempt as well as the indignation of his country who can hesitate which to embrace.” The next day the jury declared Burr “not guilty.”

Jefferson was furious with Marshall’s decision and how, in the President’s opinion, the Chief Justice had acted in a biased manner against the Jefferson administration while conducting the trial. Jefferson was tired of being thwarted by Marshall and wanted to pursue impeachment proceedings against the Chief Justice, but he was dissuaded by his advisors, including U.S. Attorney George Hay who prosecuted the case. Hay delicately pointed out to the President that he had long protected Wilkinson, who was discredited on the witness stand, from criminal charges. If Jefferson asked the House to advance impeachment actions against Chief Justice Marshall, Jefferson’s knowledge of Wilkinson's duplicity and his failure to act upon that knowledge would come to light. And if that were to happen, the real loser in the court of public opinion would be Jefferson and not Marshall. Since the President recognized this reality, Jefferson swallowed his bitterness and moved on to other matters.

As for Burr, he may have won the trial, but that was all. Scorned by his own party and burned in effigy at countless gatherings across the country, Burr left for Europe and a self-imposed exile that lasted for four years. Upon his return, he resumed his law practice in New York but never again sought public office.

Next week, we will discuss the legacy of John Marshall. Until then, may your motto be “Ducit Amor Patriae,” love of country leads me.

The first few decades of the 19th century were an exciting time for the American judiciary, at least as exciting as anything involving attorneys and judges can be. From the time Thomas Jefferson was sworn in as President on March 4, 1801, through the presidency of Andrew Jackson, there was a tremendous antagonism between the populist Executive branch and the Supreme Court, the last bastion of Federalism. This unprecedented tension between the Executive and the Judiciary made for frequent and intense conflicts, arguably more frequent and more intense than during any other period in our country’s history.