American Judiciary, Part 2: An Independent Federal Judiciary

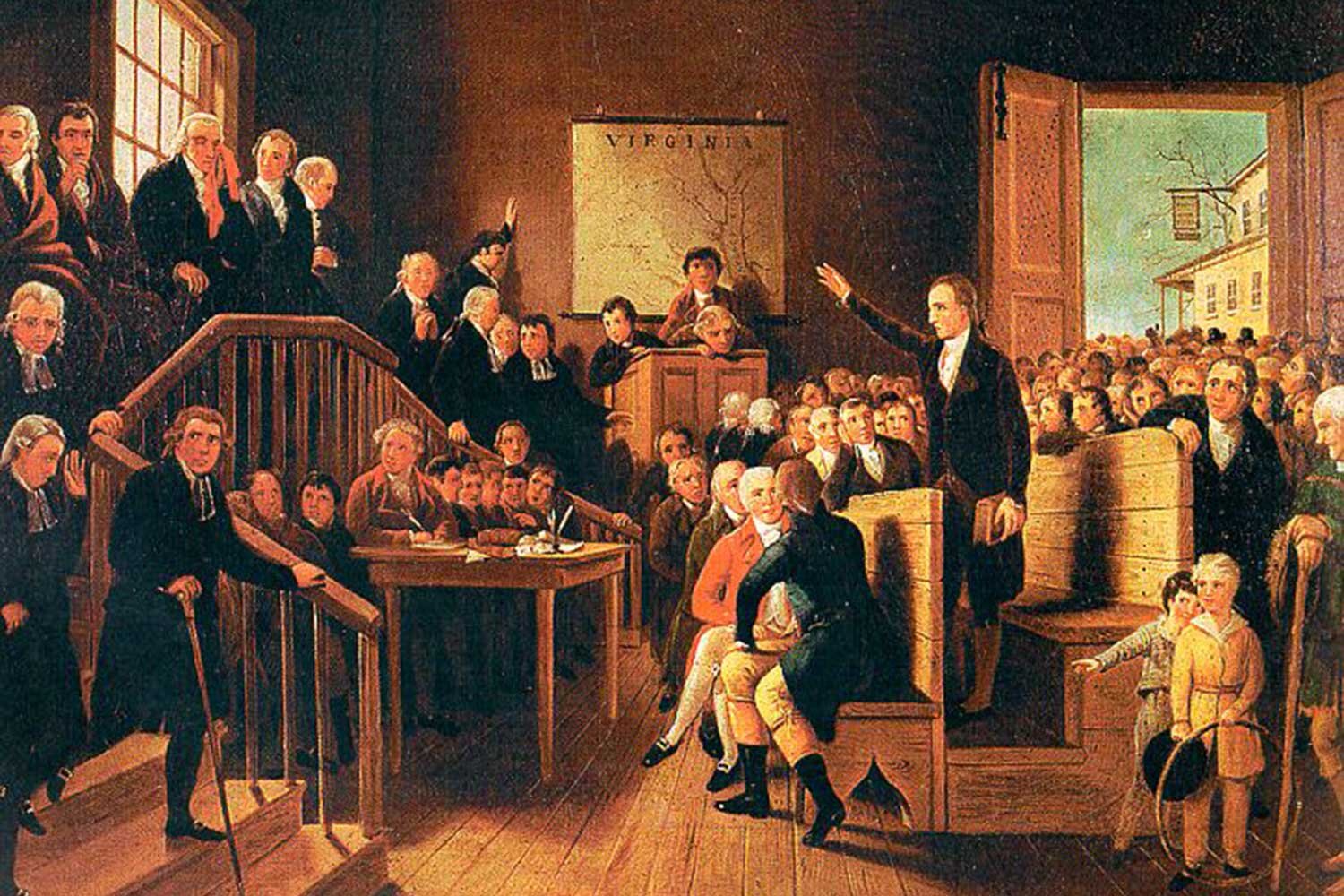

One of the foundational governing principles of the Constitution created at the Philadelphia Convention in the summer of 1787 was a separation of powers between the national legislative, executive, and judicial branches. But while significant operating concepts and responsibilities were set forth for Congress and the executive in the Constitution, the delegates barely addressed the specific structure of the judicial branch. Additionally, while most agreed the judiciary must be independent, the power it should wield was greatly debated.

In part, this lack of guidance in the Constitution regarding the federal judiciary was due to its novel nature as there had not been a national or centralized court system under the Articles. Like most innovations that have the potential to upset the status quo, the national judiciary was viewed by many with wary eyes, uncertain of how it would impact the existing governing system. While Southerners worried that this new judicial power might move against slavery, those that owed legitimate debts to British creditors grew concerned that federal judges would require debtors to finally pay their obligations in accordance with the terms of the Treaty of Paris, debts that state courts had forestalled. And still others thought the lack of a federal Bill of Rights might lead to a disregard of basic defendant rights like trial by jury within the federal system that were enshrined at the state level.

“John Jay.” National Gallery of Art.

Because Article III of the Constitution stated “…judicial power shall be vested in one supreme Court and in such inferior courts as Congress may from time to time ordain and establish,” one of the first pieces of legislation crafted in the first Congress was to address these “inferior courts.” Interestingly, Article III did not specify how many Supreme Court justices there should be or when it should meet or how often, and those matters were addressed as well. The resulting law was the Judiciary Act of 1789, signed into law by President George Washington on September 24, which created two additional tiers to the federal court system to augment the Supreme Court, thirteen circuit courts and district courts, and determined that “The supreme court of the United States shall consist of a chief justice and five associate justices” (John Jay from New York was the first Chief Justice) and that it would meet in two sessions each year in the nation’s capital. The Act also established the office of Attorney General (Edmund Randolph of Virginia was the first to fill this position) whose primary responsibility was to represent the interests of the government in cases heard by the Supreme Court.

The Judiciary Act also assigned Supreme Court justices to districts and required them “to ride the circuit” which meant that Supreme Court justices would travel, often by horseback, to hold session at a circuit court in their district. Travel conditions in early America were deplorable as roads were barely passable and places to stay were few and far between, and the ones that were in existence were wretched. The justices, who tended to be older men, found the travel to be terribly hard on them is one reason many men declined appointments to the Supreme Court. The other major issue with this system was that justices would hear cases in circuit court and then, if appealed, would hear the exact same case at the Supreme Court somewhat lessening its appellate nature.

Concurrently with the debate over the judiciary, Congress developed a list of Constitutional amendments to guarantee individual rights at the federal level, perhaps the gravest concern among Anti-Federalists. On September 25, twelve were approved and submitted to the states for ratification in accordance with Article V of the Constitution; ultimately ten would be ratified on December 15, 1791, and come to be known as our Bill of Rights. Interestingly, in an indication of the anxiety with which the new federal judiciary was viewed, four of the ten amendments dealt with individual rights when accused of a crime and in court proceedings.

As one of his executive duties, President Washington nominated the first six Supreme Court justices and would eventually nominate eleven men to the High Court, the most of any president. But his appointments were based as much on political orientation and philosophy as on judicial experience. The President believed that the administration of justice was “the strongest cement of good government” and that only the most trustworthy and honorable men should be entrusted with those duties. Quite naturally, in his eyes, the men who fit this bill were strong proponents of a robust national government. At a time when judges were openly political, three of the six original Supreme Court justices had just a few months’ experience as a judge at any level, but they were all staunch Federalists. The importance of one’s political leanings was also true for the federal district judgeships as only eight of the twenty eight district judges in the 1790s had ever held a high level state judgeship before being elevated to the federal bench, but they all supported the Washington and Adams administrations.

In the late 1790s, the political winds in the country began to shift from the Federalist camp to the so-called party of the people, the Democratic-Republicans, whose leader was Thomas Jefferson. In the election of 1800, sometimes called the Revolution of 1800, Jefferson defeated John Adams, the Federalist incumbent, for the Presidency and both houses of Congress flipped to Democratic-Republican control. Thus, at the dawn of the new century, the Federalists had lost control of two of the three branches of the national government. However, they still had a stranglehold on the judiciary as all federal judges thus far appointed were Federalists and they were appointed for life. The incoming President recognized this as Jefferson stated, “The Federalists have retired into the Judiciary as a stronghold, and from that battery all the works of republicanism are to be battered down.”

Not surprisingly then, in the final months of his administration, President Adams and the lame duck Federalist Congress put things in place to improve the existing national court system and, at the same time, further cement Federalist control of the national judiciary, now seen by Federalists as the last bastion against the radical excesses of the Jeffersonian Republicans.

Next week, we will discuss the Adams-Jefferson struggle for control of the federal judiciary. Until then, may your motto be “Ducit Amor Patriae,” love of country leads me.

The first few decades of the 19th century were an exciting time for the American judiciary, at least as exciting as anything involving attorneys and judges can be. From the time Thomas Jefferson was sworn in as President on March 4, 1801, through the presidency of Andrew Jackson, there was a tremendous antagonism between the populist Executive branch and the Supreme Court, the last bastion of Federalism. This unprecedented tension between the Executive and the Judiciary made for frequent and intense conflicts, arguably more frequent and more intense than during any other period in our country’s history.