American Judiciary, Part 8: The Impeachment of Samuel Chase

There has been only one instance in our nation’s history of a United States Supreme Court Justice being impeached, and that occurred in 1804 during a significant political tussle over the independence and power of the judiciary. The justice in question was Samuel Chase and his alleged crimes seem trivial in retrospect, but Chase was simply a pawn in an ongoing battle of wills between two American icons, President Thomas Jefferson and Chief Justice John Marshall that took place in the early 1800s. And the decision reached in his case would have a profound impact on the future of the country.

In February 1803, the president’s Democratic-Republicans brought impeachment charges against John Pickering, a federal district court judge in New Hampshire. Pickering was a relatively easy target for the Democratic-Republicans as Pickering not only had mental issues but was prone to drunk rantings in the middle of his court sessions. Despite his grave failings, Federalists argued that the case against Pickering was politically motivated and pointed out that according to the Constitution, Pickering could only be impeached for “high crimes and misdemeanors” and insanity did not fit those crimes. Regardless, Pickering was impeached by the House with the requisite two thirds majority and the Senate followed suit, convicting Pickering on March 12, 1804, and dismissing him from office.

Taking their direction from the president, Democratic-Republicans immediately turned their attention to a bigger fish, Supreme Court Justice Samuel Chase, and within an hour of Pickering’s conviction, the House voted to begin an inquiry into Chase’s behavior. Chase, who had been appointed to the Supreme Court in 1796 by President George Washington, was a staunch Federalist who did not hide his political opinions. Chase had expressed his partisan views while presiding in circuit court over the trials of James Callender and John Fry, two ardent Democratic-Republicans accused of violating the Sedition Act. Chase later lectured a Baltimore grand jury on the dangers of Jeffersonian republicanism. This last outburst caused President Jefferson to write to Representative Joseph Nicholson, “you must have heard of the extraordinary charge of Chase to the grand jury of Baltimore. Ought this seditious and official attack on the principles of our constitution go unpunished?”

Although Chase’s behavior was certainly biased and his attacks openly partisan, he still had not committed anything resembling “high crimes and misdemeanors.” Regardless, the trial moved forward in the House of Representatives, led by John Randolph of Virginia, a brilliant if erratic legislator. On December 4, 1804, the House voted on eight articles of impeachment against Chase, charges that essentially accused him of acting improperly and with partiality in his courtroom. In a mostly party line vote, all eight charges of impeachment were adopted by huge margins in the House and referred to the Senate for trial.

“Luther Martin.” New York Public Library.

But the Democratic-Republicans were after much more than simply removing an obnoxious Federalist judge from the bench. The Chase trial was part of their larger plan to end Federalist control of the judiciary and permanently reduce its independence. For two years, the Jeffersonians had known nothing but success in their efforts; repealing the Judiciary Act of 1801 and passing their own judicial reforms in 1802 as well as removing Federalist judges from office at both the national (Judge Pickering) and state (Pennsylvania Judge Alexander Addison) level on dubious charges. Furthermore, most people felt that if Chase were convicted, Chief Justice Marshall would be the next to go.

Senator William Branch Giles of Virginia, an ardent Jeffersonian, wanted to establish the precedent that impeachment was not a criminal proceeding but a device by which the legislature could remove any judge with whom it disagreed, a doctrine significantly different from what the Constitution stated. Giles declared "Removal by impeachment was nothing more than a declaration by Congress to this effect: you hold dangerous opinions, and if you are suffered to carry them into effect you will work the destruction of the nation.” In the eyes of many, including some Democratic-Republicans, this was a very dangerous path to take and could lead to the wholesale removal of judges with every new administration. This philosophy, if carried into effect, would thwart the Constitutional objective of maintaining an independent judiciary that simply interpreted the law regardless of who was in power.

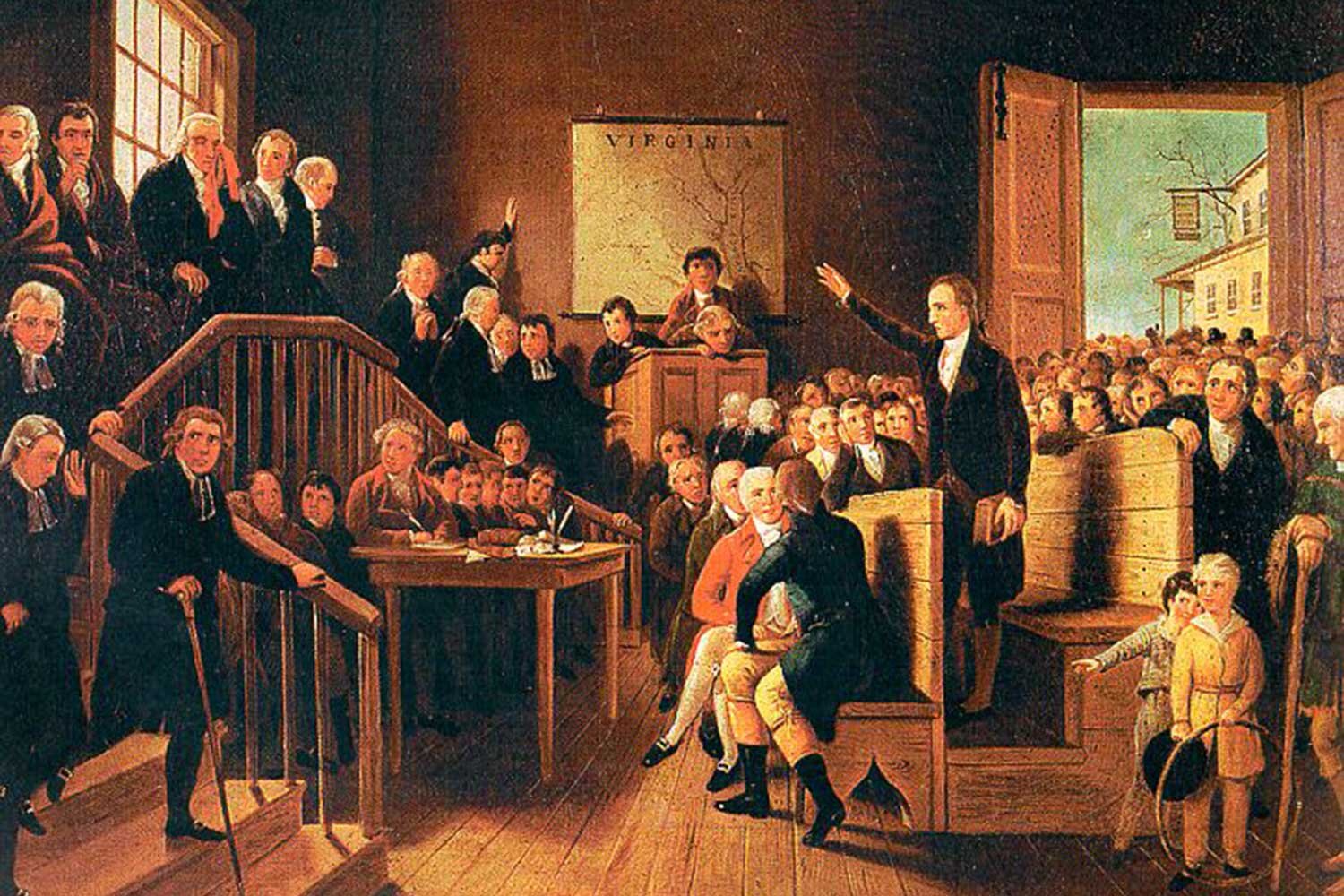

The Senate convened on February 4, 1805, to an overflowing gallery, and over the course of four weeks, fifty-two witnesses were called, including Chief Justice Marshall and Justice Chase. Both sides brought out their best attorneys to argue the case; Democratic-Republicans, led by John Randolph, acted as the prosecution, while the Federalist defense team included Luther Martin, Charles Lee, and Joseph Hopkinson. As the Republicans unveiled their case and explained their accusations, the trivial nature of these charges became apparent and all in attendance except the most ardent Democratic-Republicans could see that this was clearly a partisan attack launched for political gain.

When Luther Martin rose to defend Chase, he asked the core question: did Chase's behavior fit the category by which a judge could be impeached according to the Constitution, i.e., “high crimes and misdemeanors.” Luther pointed out that while Chase may have exhibited questionable behavior, it was “rather the want of decorum, than the commission of a high crime and misdemeanor.” Luther closed his argument by reminding the Senate that the United States is a “government of laws. But how can it be such, unless the laws, while they exist, are sacredly and impartially, without regard to popularity, be carried into execution? Our property, our liberty, our lives, can only be protected and secured by such (independent) judges.”

Luther’s comments and the weak evidence presented against Justice Chase had a profound effect on all Senators, including many Democratic-Republicans, who worried about the dangerous precedent a conviction on purely political grounds would have on the future of the judiciary and the country. And when the Senators voted on March 1, despite Democratic-Republicans holding a 25-9 majority in the Senate, none of the articles of impeachment attained the required two thirds majority (23 votes) to convict Chase.

Not surprisingly, President Jefferson was furious with the Senate but, fortunately for the country, more moderate views had prevailed.

Next week, we will discuss the conspiracy of Aaron Burr. Until then, may your motto be “Ducit Amor Patriae,” love of country leads me.

The first few decades of the 19th century were an exciting time for the American judiciary, at least as exciting as anything involving attorneys and judges can be. From the time Thomas Jefferson was sworn in as President on March 4, 1801, through the presidency of Andrew Jackson, there was a tremendous antagonism between the populist Executive branch and the Supreme Court, the last bastion of Federalism. This unprecedented tension between the Executive and the Judiciary made for frequent and intense conflicts, arguably more frequent and more intense than during any other period in our country’s history.