American Judiciary, Part 9: The Burr Conspiracy

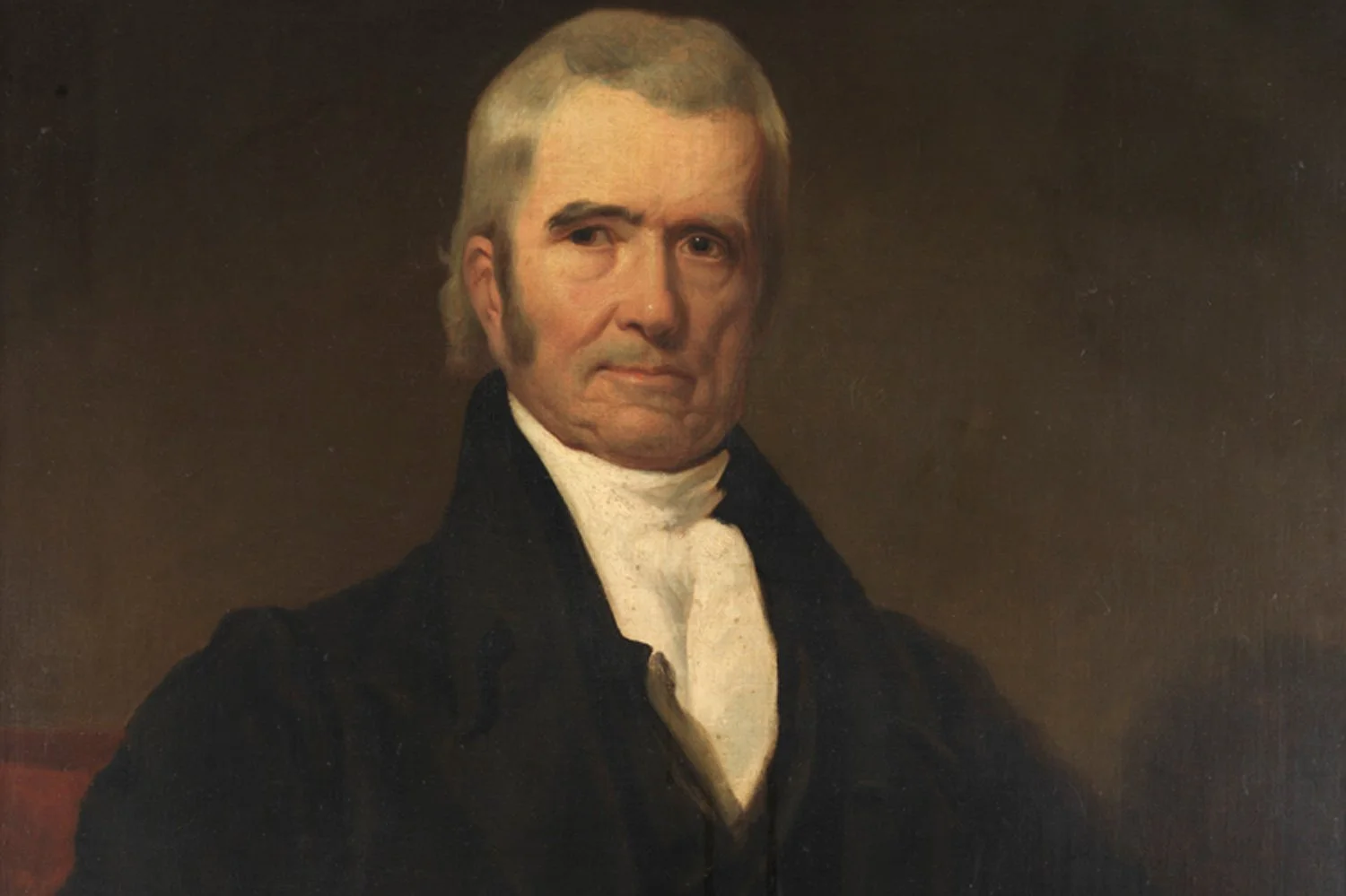

Aaron Burr was one of the most talented of our founding fathers, a Lieutenant Colonel in the Continental Army, an accomplished attorney in New York, a United States Senator, and the third Vice President. But Burr also happens to be the only sitting or former President or Vice President ever tried for treason in arguably the most important criminal trial in American history. And Burr’s trial brought into conflict once again two of the great men from our founding era, President Thomas Jefferson and Chief Justice John Marshall.

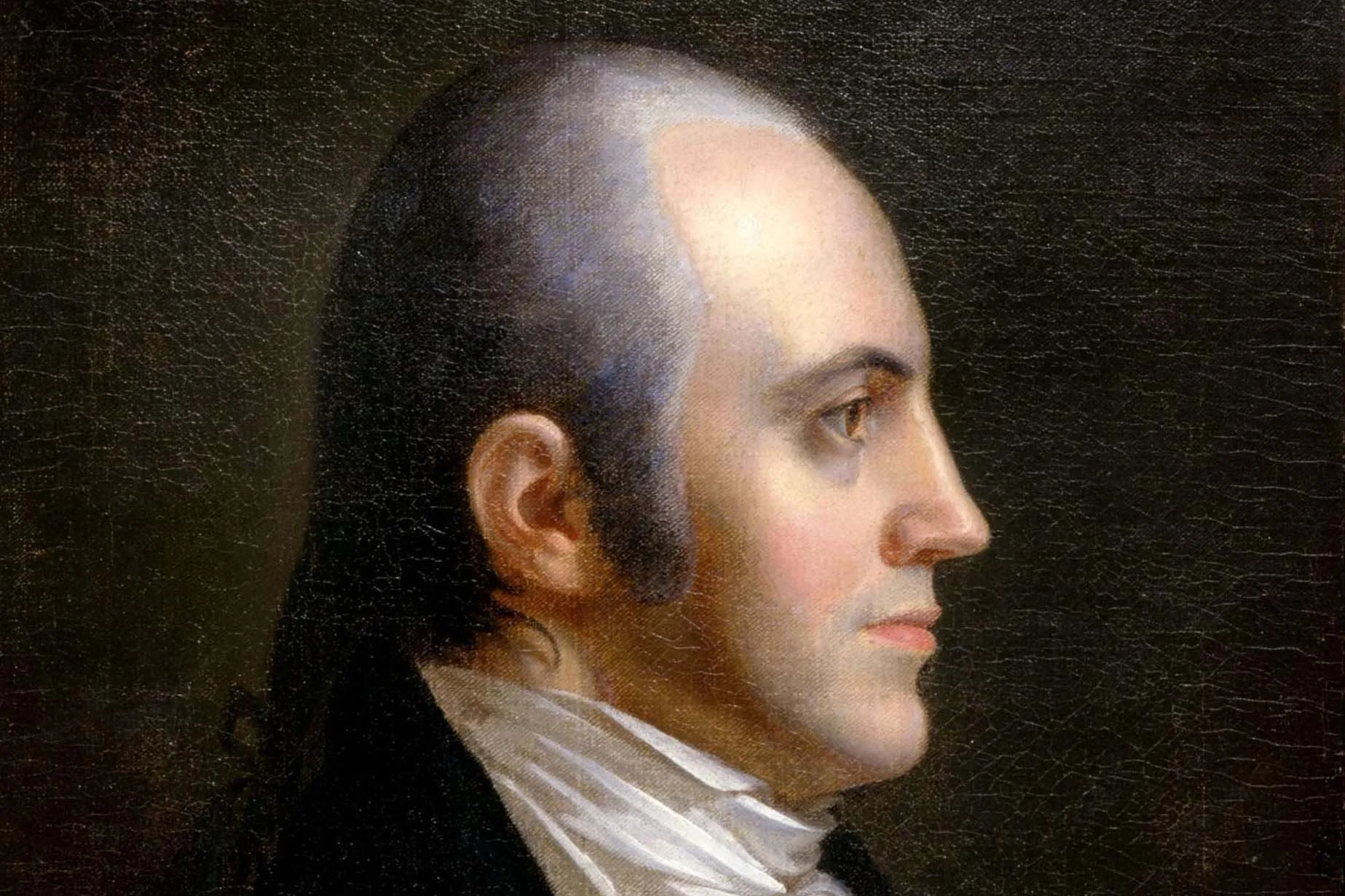

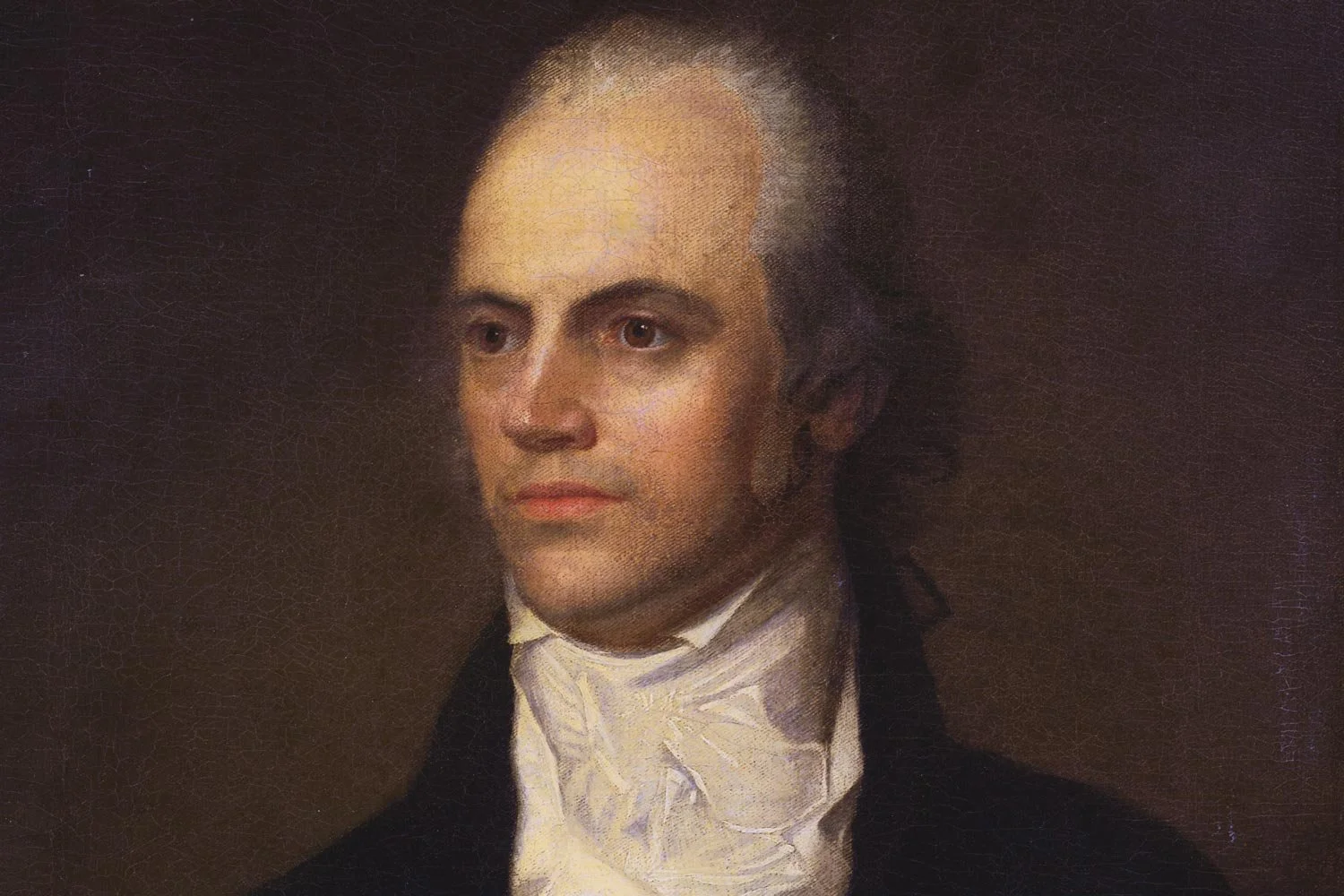

Aaron Burr was born on February 6, 1756, into a prominent family in Newark, New Jersey. His father, Aaron Burr, Sr., was the President of the College of New Jersey (later Princeton University) but died one year after his son’s birth. Aaron Jr’s mom died the next year, leaving him an orphan at age two and he was raised by his maternal uncle, Timothy Edwards. Burr was very bright and enrolled in the College of New Jersey at the tender age of thirteen and graduated three years later. When war broke out in 1775, Burr left law school and volunteered for service in the Continental Army, marching to Quebec with Colonel Benedict Arnold, enduring the harsh winter of 1777-78 at Valley Forge, and later displaying great courage and leadership on battlefields such as Monmouth before resigning his commission in 1779 due to health issues.

Burr began practicing law in New York in 1782 and soon ventured into politics, elected as a state Assemblyman in 1784 and a United States Senator in 1791. He ran unsuccessfully for President in 1796, finishing fourth, and again in 1800, this time tying for the most electoral votes with Thomas Jefferson, who was declared President by the House of Representatives with Burr being named Vice President. Burr’s decision to not voluntarily step aside in favor of Jefferson made Burr an arch enemy of Jefferson’s and an outcast in the Democratic-Republican party.

“Andrew Jackson.” Wikimedia.

Upon leaving office in the spring of 1805, Burr was a ruined man, financially and politically, with his reputation in tatters. He was essentially ostracized from the Democratic-Republican party by some of the very men he helped bring to power in the election of 1800 and Federalists hated him for many reasons including the killing of Alexander Hamilton in their infamous duel. But still Burr had his admirers in the lands west of the Appalachians, including several western Senators and fellow former officers in the Continental Army who had moved there after the war. And it was here that a desperate Burr attempted to rescue his fading fortunes by resurrecting a plan he had first envisioned a decade earlier to invade Mexico and set up a government with Burr at its head.

Over the next year, Burr traveled to several western towns including Nashville, where he was hosted on three occasions by Andrew Jackson, then Major General of the state militia, and New Orleans, whose leaders gave Burr a hero’s welcome. Burr’s plan to seize part of New Spain (Mexico) was enthusiastically embraced at all his stops by westerners who viewed Spain as their main adversary. Burr, who was nothing if not ambitious, cast a wide net trying to ensnare support wherever he could, contacting American naval heroes Thomas Truxtun, his intimate friend, and Stephen Decatur, as well as William Eaton who had led the 1805 invasion of Tripoli during the First Barbary War, but they all turned away from Burr’s scheme. Burr even made overtures to British officials and, according to Anthony Merry, British Minister to the United States, offered to detach Louisiana from the United States and annex it to Great Britain in exchange for a million dollars and three British ships of the line to secure the Gulf of Mexico. But British officials were skeptical of Burr’s scheme and took no action.

But Burr was more successful when he solicited the assistance of General James Wilkinson, a born intriguer and a powerful ally as the senior officer in the United States Army and the Governor of the Territory of Louisiana. Wilkinson, who was one of the greatest scoundrels in American history and had played a role in the Newburgh Conspiracy and was a secret paid informant of the Spanish government, pledged his support to Burr. Burr’s far-flung web also captured the interest of Harman Blennerhassett, a wealthy Irish immigrant who owned an estate on an island in the Ohio River just south of today’s Parkersburg, West Virginia which Burr planned to use as a staging area for his enterprise.

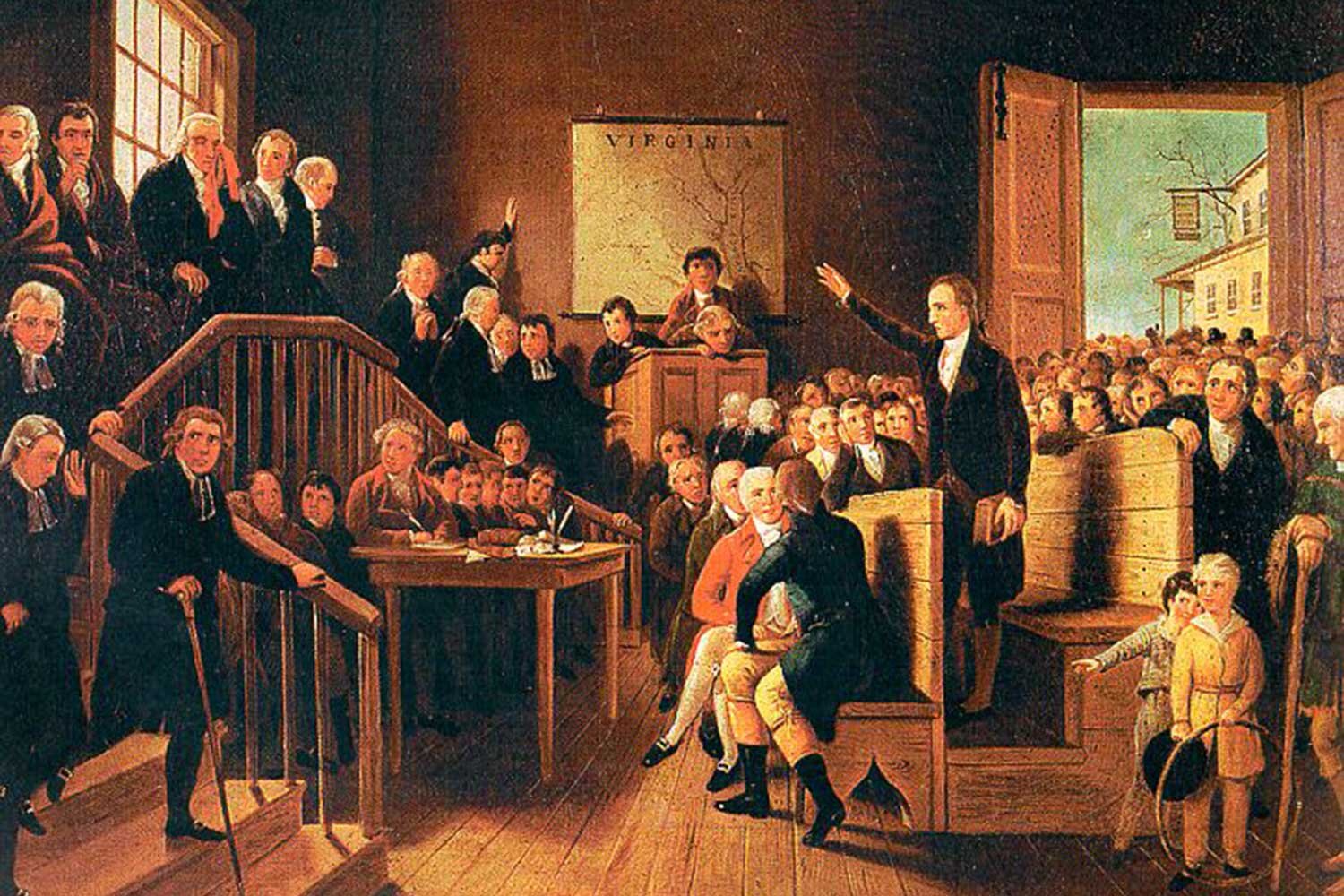

But soon rumors were whispered by Burr’s enemies that Burr planned to separate the old Southwest Territory (Alabama, Mississippi) and/or Louisiana from the United States and create a new country there or possibly lead the country into a war with Spain by invading Mexico with a private army. Not surprisingly, these rumors found their way into the eastern press and to the desk of President Jefferson, but the President declined to take any action thinking the accusations false and the attacks politically motivated. But Kentucky District Attorney Joseph Daviess, a Federalist and brother-in-law of John Marshall who had sent several letters to Jefferson months earlier informing him of the conspiracy, grew frustrated at President Jefferson’s apparent indifference to Burr’s activities and, in November 1805, brought charges of treason against Burr. A young Henry Clay, who had fallen under Burr’s spell, masterfully defended the former Vice President and the grand jury dismissed Daviess’ charges on two separate occasions.

With Burr’s scheme now in the open, General Wilkinson began to worry that Burr’s plan would fail and that that failure would engulf Wilkinson and lead to the General’s demise. Naturally, Wilkinson did what any self-respecting scoundrel would do; he turned on his partner to save himself. In July 1806, Burr had sent a cyphered message to Wilkinson providing an update to the General on the status of their enterprise. In October, after doctoring the letter to remove anything that might cast aspersions on himself, Wilkinson forwarded Burr’s letter to President Jefferson with his own letter stating his shock and indignation at Burr’s actions. The following month, President Jefferson issued a proclamation in which he informed the country of the plot, declared Burr’s guilt, and issued a warrant for his arrest.

Next week, we will discuss the treason trial of Aaron Burr. Until then, may your motto be “Ducit Amor Patriae,” love of country leads me.

The first few decades of the 19th century were an exciting time for the American judiciary, at least as exciting as anything involving attorneys and judges can be. From the time Thomas Jefferson was sworn in as President on March 4, 1801, through the presidency of Andrew Jackson, there was a tremendous antagonism between the populist Executive branch and the Supreme Court, the last bastion of Federalism. This unprecedented tension between the Executive and the Judiciary made for frequent and intense conflicts, arguably more frequent and more intense than during any other period in our country’s history.