American Judiciary, Part 1: Courts in Early America

The court system in Colonial America, not surprisingly, mirrored that of Great Britain and became one of the great sources of discontent as American colonists moved towards independence. The main issue was over who would control or have the greatest influence on the judiciary. Because judges in the British colonies were appointed and paid for by the Crown, they were naturally beholden to the King and seen as simply an extension of royal authority. Quite naturally, unhappiness with the King grew into unhappiness with colonial judges.

With the rise of republicanism and its belief that the will of the people is supreme, colonial American leaders sought to right this perceived wrong by making judges dependent on legislatures elected by the people. Consequently, as states began to create their own constitutions after 1776, most took the power of appointing judges away from the governor and gave it to the legislature.

Part of the problem was that much of the British legal world was centered on common law; a system based largely on unwritten legal precedents rather than written codified laws. In other words, new judicial decisions were reached consistent with how previous cases that were similar in nature had been decided and not necessarily because they did or did not violate a specific statute. As a result, there were relatively few statutes on the books and judicial interpretation had an outsized influence on legal matters, and that subjectivity always seemed to favor the Crown. As Thomas Jefferson wrote in 1776, most Americans viewed judicial decision making as “the eccentric impulses of whimsical, capricious designing men.” It did not help that judges generally had been lawyers and lawyers were strongly disliked by the people who resented how they manipulated the arcane mysteries of common law to their own advantage. Many felt that having legislatures write down the laws would eliminate the need to rely on common law interpretation and thus greatly restrict the power of lawyers and judges.

Following the Declaration of Independence and the creation of a central authority in the Continental and Confederation Congresses, legislative leaders pointedly did not create a national judicial branch. Instead, because each state considered itself a sovereign entity, early legislators thought all legal decisions should be rendered in the existing state courts. However, in the following decade, the flaws in this system became apparent. Because the courts were essentially an extension of the popularly elected legislature, the rights of the minority were often denied in order to satisfy the desires of the majority. Additionally, each election brought new views and voices to the assemblies and with changes to the legislature came changes to the existing laws, thereby creating confusion and eroding a sense of stability in the government.

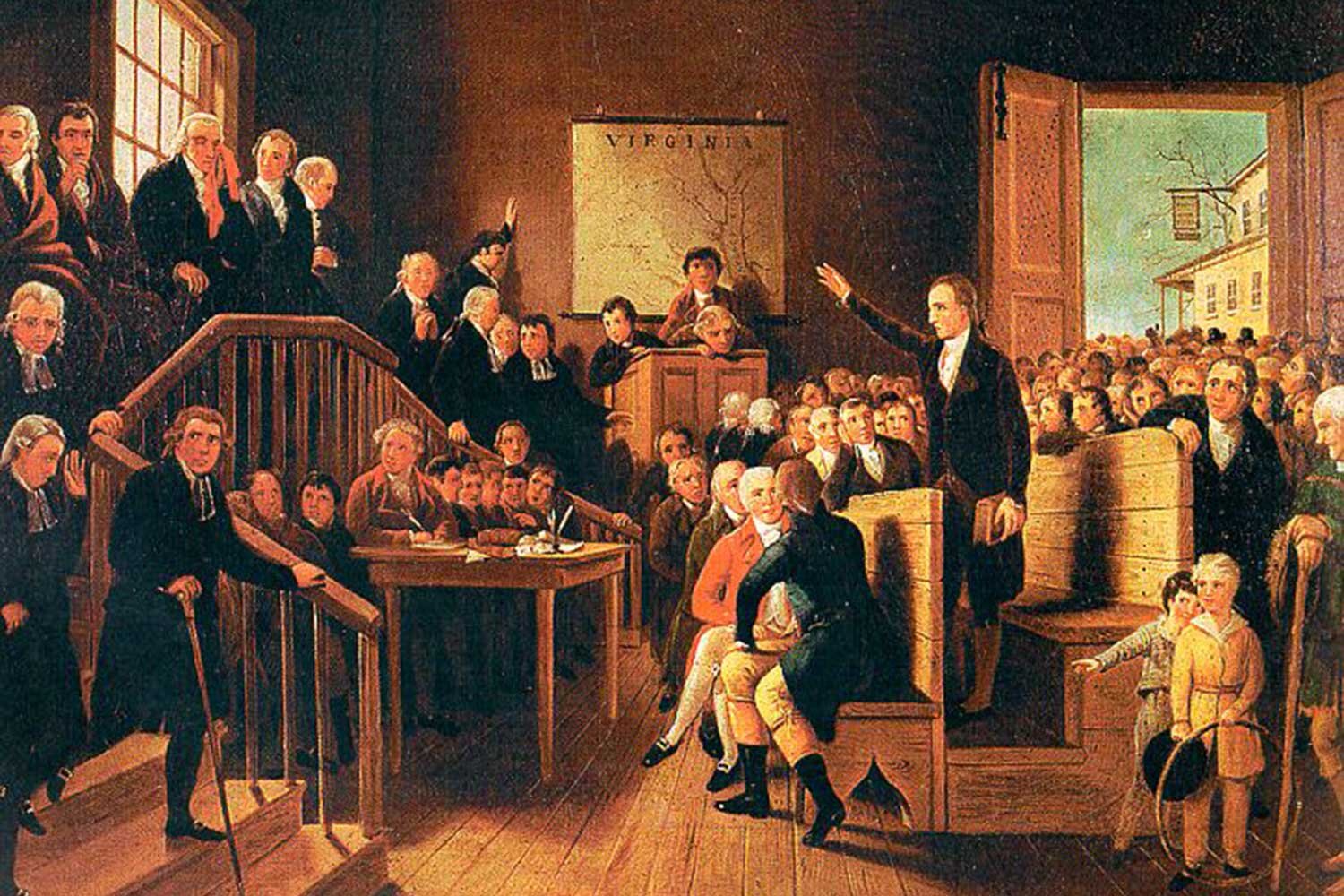

In an example of how dependent judges were on the legislature, when the assembly of Rhode Island did not care for the behavior of the state Supreme Court, it simply elected a new court the following year. And even in those states that did grant tenure during good behavior to judges, assemblies generally controlled the salaries and fees paid to judges and the power of removal was usually required only by a majority of the legislature.

Perhaps worst of all, especially for the commercial class, was the vulnerability of property under the legislative-driven legal system in America. Because debtors generally outnumbered creditors and because much of the debt was owed by Americans to British creditors from before the war, the interest of creditors was often overlooked by politicians. But as more moderate republicans entered the business world, they too came to see the need for judicial reform and understood that only an independent judiciary could act as a check on legislative excesses, especially regarding property rights and debt obligations. But the concept of a national judiciary was new and exactly what that would look like and the power it would possess was open to debate.

“James Madison.” Wikimedia.

In the early 18th century, French political philosopher Montesquieu theorized about governmental separation of powers that included an independent judiciary, co-equal to the legislative and executive branches. The timing of Montesquieu’s teachings coincided with the rise of an enlightened group of American political leaders such as John Adams, Thomas Jefferson, and James Madison who sought to create that idealized nation suggested by the Frenchman. As a result, when the Constitutional Convention convened in the summer of 1787, creating an independent federal judiciary was one of the key objectives for the Constitutionalists.

Still, the concept of a national judiciary was new to the nation and to states’ rights advocates known as Anti-Constitutionalists or Anti-Federalists, the thought of yet another source of centralized power, especially one independent of the will of the people, was viewed as a great danger to the sovereignty of the states. To dispel these concerns, Alexander Hamilton penned a series of articles pertaining to the federal judiciary as part of a larger series that has come to be known as the Federalist Papers. In Federalist 78, the most quoted of these articles, Hamilton explains that the judiciary has the authority to determine if the acts of Congress are constitutional and the remedy for legislative excesses if they are not. This concept, critical to a check on legislative overreach, is known as judicial review and was confirmed by the Marshall Court in the 1803 case of Marbury v Madison.

But despite this power of judgment, Hamilton argued that “of the three powers (legislative, executive, judiciary), the judiciary is next to nothing” and further points out, “The Executive not only dispenses the honors but holds the sword of the community. The Legislature not only commands the purse but prescribes the rules by which the duties and rights of every citizen are to be regulated. The Judiciary, on the contrary, has no influence over either the sword or the purse.”

In any event, the Constitution was ultimately adopted and one of the first orders of business of the new United States Congress was to put some structure to the federal court system.

Next week, we will discuss the creation of the national judiciary. Until then, may your motto be “Ducit Amor Patriae,” love of country leads me.

The Colony of Virginia was established at Jamestown by the Virginia Company in 1607 as a for-profit venture by its investors. To bring order to the province, Governor George Yeardley created a one-house or unicameral General Assembly on July 30, 1619.