American Judiciary, Part 3: Last Bastion of the Federalists

After the Federalists were voted out of office in the fall of 1800 by Thomas Jefferson’s Democratic-Republican Party, the need for reform to the judicial system, the last stronghold of Federalist authority, became the most pressing concern of the outgoing Adams administration. The idea was not new as it had been a desire of Federalists to fix the national court system for years, but between the Quasi-War with France and ongoing diplomatic struggles with both Great Britain and France, President Adams had not made judicial reform a priority. But with time running out to do so, on February 13, 1801, President Adams signed into law the Judiciary Act of 1801, sometimes referred to as the Midnight Judges Act because Jeffersonians contended that outgoing President Adams signed commissions until midnight of his last day in office, a rumor that was not true.

The stated purpose of the Act was “to provide for the more convenient organization of the Courts of the United States” by expanding the federal judiciary and correcting flaws in the Judiciary Act of 1789. The Act of 1801 reduced the number of justices on the Supreme Court from six to five, expanded the number of judicial districts from seventeen to twenty-two, and reorganized the circuit courts which created new judgeships and other positions. Interestingly, total salaries for these new positions only amounted to $31,500, with another $15,000 allocated for expenses. Despite the cynicism voiced by Jeffersonian newspapers, this expansion of the circuit courts was a sound idea as it created more local judgeships, allowing judges to hear more cases and to shorten the delay in bringing cases to trial. Additionally, it relieved Supreme Court justices of the onerous duty of “riding the circuit” to hold court in distant areas which freed them up to hear more cases in Washington.

“Oliver Ellsworth.” National Portrait Gallery, Smithsonian Institution.

Accordingly, on March 2, outgoing President Adams, two days before the end of his administration, submitted the names of nearly sixty Federalist supporters to Congress for approval to fill these newly created positions, sixteen federal judgeships and forty-two justices of the peace. The following day, the Senate approved these nominations en masse which the President signed and gave to Secretary of State John Marshall to deliver to these new appointees. Marshall was able to deliver most of these commissions before Adams’ administration came to an end, but not all, including many justices of the peace commissions in nearby Washington county, an omission that would have historic consequences. Interestingly, Marshall was then filling two roles as he had been named by Adams as the fourth Chief Justice of the Supreme Court on February 4, replacing Oliver Ellsworth who had recently retired.

Naturally, when newly elected Thomas Jefferson became president and his Democratic-Republican Party took over both houses of Congress, they moved quickly to reverse Adams’ judiciary measures. Decrying the appointments as corrupt patronage and an unwarranted expense, the Democratic-Republicans first repealed the Adams Judiciary Act of 1801, which terminated the newly created circuit courts and, consequently, revoked the tenure of the newly appointed judges, the one and only time in our country’s history when the tenure of federal judges was revoked. Federalists complained about this apparent violation of the Constitution which states judges cannot be removed during periods of “good behavior.” But Democratic-Republicans noted that they did not revoke the tenure of any judges but simply eliminated the positions they filled. However, Federalists did not find this legal tap dance amusing, as Justice Samuel Chase commented, “The distinction of taking the Office from the Judge and not the Judge from the Office was…nonsensical.”

President Jefferson next signed into law his own judicial reform legislation, the Judiciary Act of 1802. This Act restored the number of Supreme Court justices back to six and restructured the circuit courts, assigning one Supreme Court Justice to each circuit whereby Supreme Court justices were once again forced to “ride the circuit,” a practice that would continue for several more decades before being abolished in 1879. To avoid any constitutional challenges from recently appointed Chief Justice John Marshall, Democratic-Republicans also passed a provision which delayed the next session of the Supreme Court until the spring of 1803, more than ten months away. The thought being that if there were constitutional challenges, by the time Marshall could rule on the legislation the termination of the judgeships would be a fait accompli, making it difficult to reverse course.

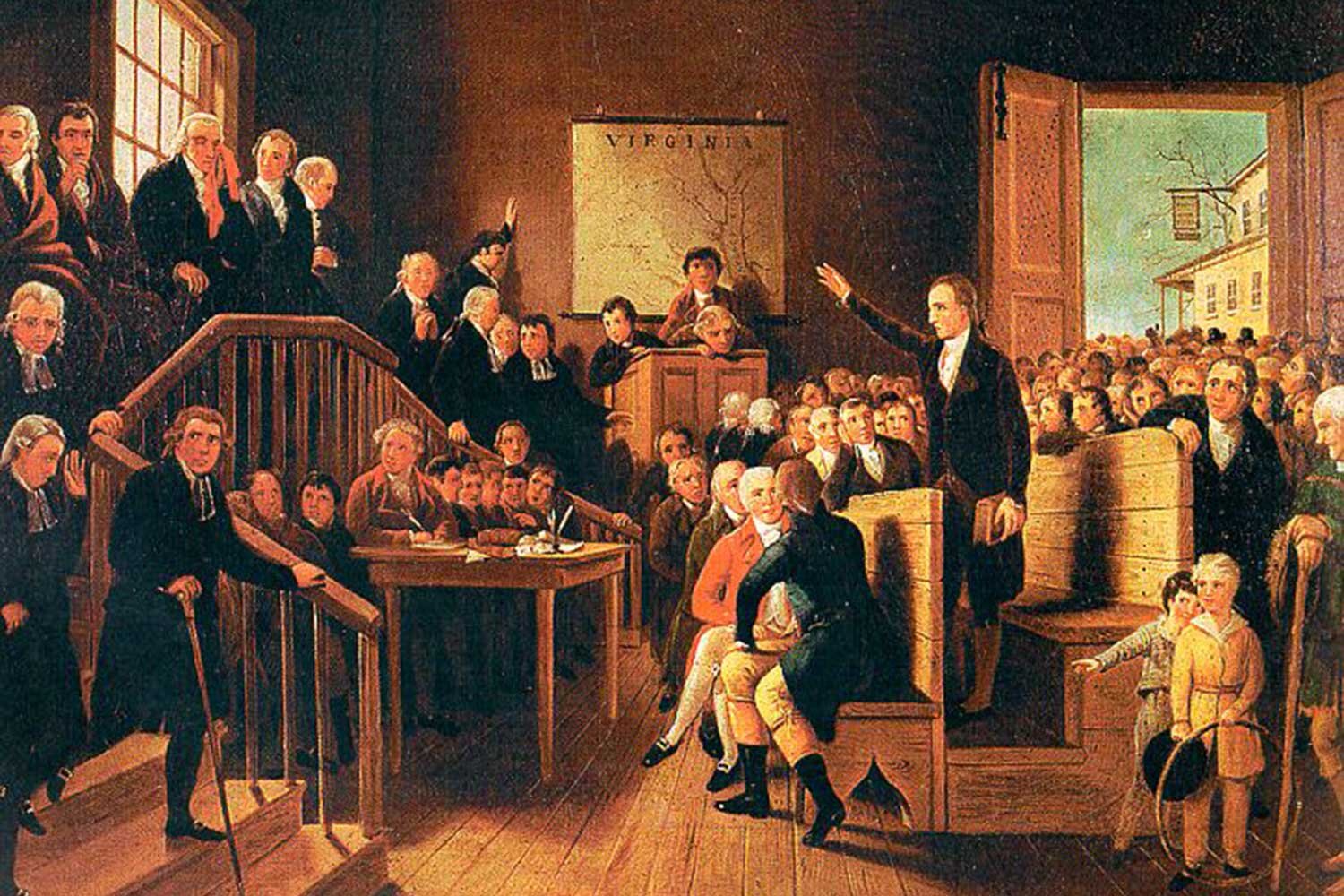

The vote by the Democratic-Republicans to repeal the Judiciary Act of 1801 was in essence a repudiation of the theory that the national judiciary could and should exercise supervisory power over the national legislature. This thinking was a seismic shift from those ideas espoused less than two decades earlier at the Constitutional Convention where it was argued that the country needed an independent national judiciary that could freely and appropriately interpret the law. At the time of the convention, nationalist theories held sway in the country driven in large measure by Alexander Hamilton and James Madison. Interestingly, Thomas Jefferson, a strong believer in state sovereignty, was not in country during the debates in Philadelphia but rather was serving as minister to France. In retrospect, his absence probably contributed to the final shape that the constitution took in the summer of 1787. But upon his return, Jefferson brought Madison and much of the country into his camp and by 1802 Democratic-Republican principles based on states’ rights and a weak national government were on the ascendancy.

Beyond the competing Judiciary Acts controversy, there was also the question of the undelivered justice of the peace commissions from the end of the Adams administration. President Jefferson and his Secretary of State, James Madison, naturally opposed all Federalist appointments and refused to deliver these commissions. Because these positions came with fairly low salaries, most appointees accepted their fate passively, but not William Marbury, a Maryland businessman and devoted Federalist. And Marbury’s undelivered commission would lead to the most consequential Supreme Court case in our nation's history, a decision that would be rendered by a man raised on the frontier of western Virginia.

Next week, we will discuss the early life of John Marshall. Until then, may your motto be “Ducit Amor Patriae,” love of country leads me.

The first few decades of the 19th century were an exciting time for the American judiciary, at least as exciting as anything involving attorneys and judges can be. From the time Thomas Jefferson was sworn in as President on March 4, 1801, through the presidency of Andrew Jackson, there was a tremendous antagonism between the populist Executive branch and the Supreme Court, the last bastion of Federalism. This unprecedented tension between the Executive and the Judiciary made for frequent and intense conflicts, arguably more frequent and more intense than during any other period in our country’s history.