American Judiciary, Part 4: The Early Life of John Marshall

John Marshall is perhaps the most impactful and influential man in American history who was never president. Almost single handedly, John Marshall created our national judiciary and established it as a branch of government co-equal to the legislative and executive branches. His rise from humble beginnings and lack of a structured education makes Marshall’s legal brilliance and lasting impact even more extraordinary.

Marshall was born on September 24, 1755, on the western frontier of the colony of Virginia in a small settlement known as Germantown. John was the first of fifteen children born to Thomas Marshall and Mary Randolph Keith, the granddaughter of Thomas Randolph of Tuckahoe, one of the most prominent families in Virginia and a second cousin of future President Thomas Jefferson. Thomas Marshall, whose family had emigrated to America in the late 1600s, earned his living as a surveyor in Fauquier County and as a land agent for Lord Fairfax, the wealthiest man in Virginia. Thomas was a powerful man of great stature and exceptionally intelligent; he was also hard working and fearless, two necessary traits for land surveyors on the frontier and for those who wished to carve their own destiny from the forest. Not surprisingly, he became fast friends with another Virginia surveyor named George Washington, with whom he had much in common.

Despite having a substantial income from his work, the Marshalls lived modestly and John was raised in a two-room log cabin which he shared with his parents and numerous siblings. Those that survived best on the harsh Virginia frontier were self-reliant, thoughtful in their purpose, and orderly in their habits; such a man was Thomas Marshall. Into this structured, morally sound frontier homestead, John Marshall was born and, not surprisingly, these wilderness experiences forged a self-confidence and emotional hardiness that those raised in softer surroundings can never acquire.

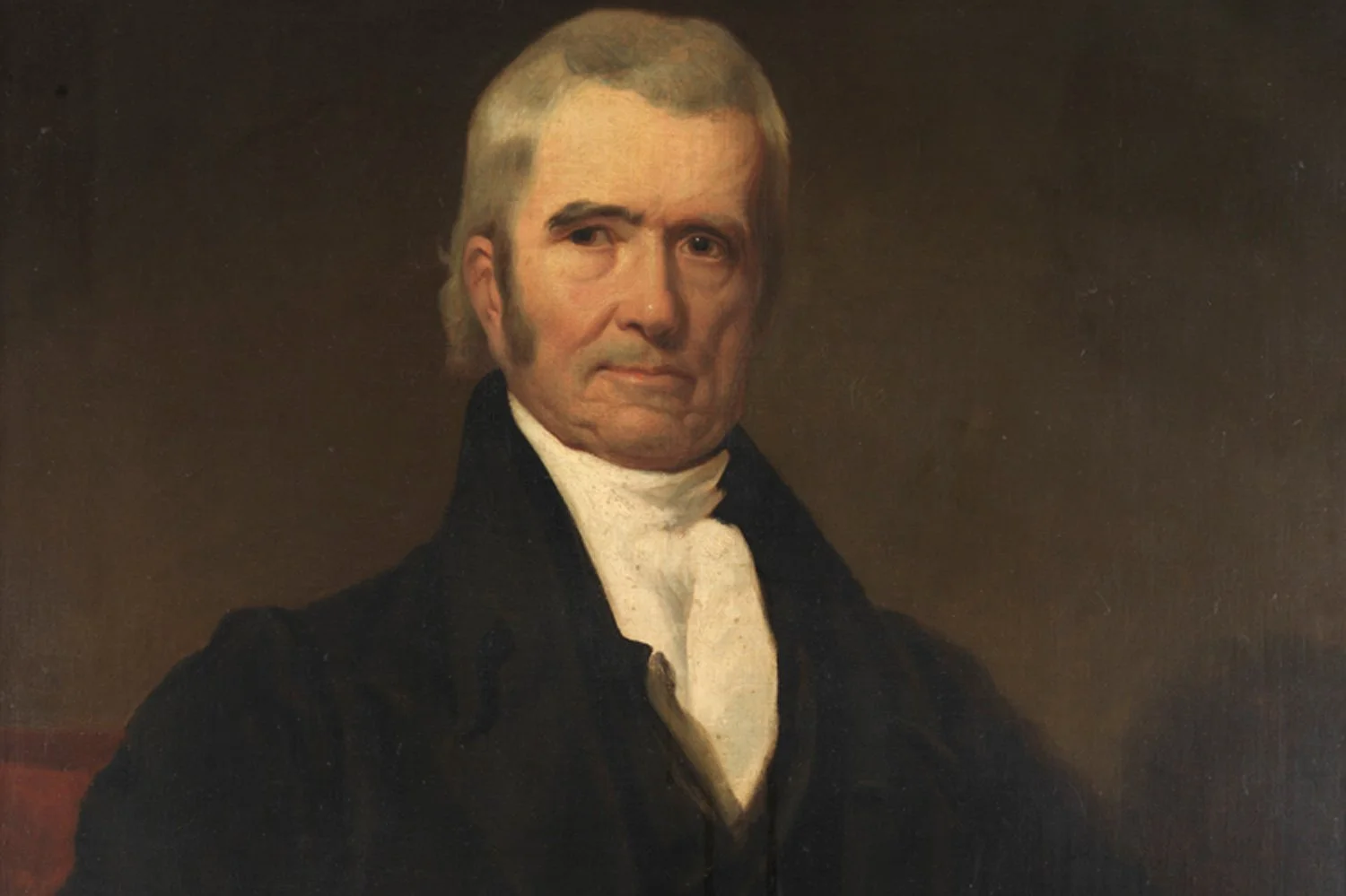

“James Monroe.” National Portrait Gallery, Smithsonian Institution.

When John Marshall was still a child, his family moved to a small valley in the Blue Ridge Mountains, roughly 30 miles west of where he was born, and it was here that Marshall spent the most formative years of his youth, often combing the surrounding mountains rifle in hand and fishing by the beautiful waters that flow through the valley near his home. Because the area was so scattered, Marshall had very few childhood companions except for his younger siblings who, as the oldest child, he helped raise and organize to get the chores done around their mountain home. Young John idolized his father who often took his oldest boy on surveying trips and, from this time together, Marshall developed a tremendous respect and admiration for his father writing “My father was a far abler man than any of his sons. To him I owe the solid foundation of all my own success in life.”

The senior Marshall was determined that his children should have all the advantages which reading gives and consequently acquired the Bible, a collection of Shakespeare’s classics, and a volume of poems by Alexander Pope. And, although formal schooling on the frontier of Virginia was difficult to obtain, Thomas did what he could to get John an education that would allow him to prosper. When John turned fourteen, Thomas was able to afford to send him away to study for one year under the Reverend Archibald Campbell, where one of John’s classmates was James Monroe, the future fifth President of the United States. The two later served together in the Continental Army and much later sparred over legal matters when Monroe became an adherent of Thomas Jefferson and his Democratic-Republican party which was often at odds with Chief Justice Marshall’s Federalist leanings.

Marshall also received several months of tutoring from a young Scottish clergyman named James Thompson, who lived with the family briefly before returning to Scotland. But that was it for Marshall’s formal education, except for a short six-week stint at the College of William and Mary studying law under George Wythe. Incredibly, the man who would develop into one of the greatest legal minds in our nation’s history and essentially create the federal judiciary had a total of less than two years of formal education. It was during this period that Marshall was introduced to William Blackstone’s Commentaries on the Laws of England, a treatise on common law, and while reading this legal classic Marshall fell in love with the law and set his sights on entering the legal profession.

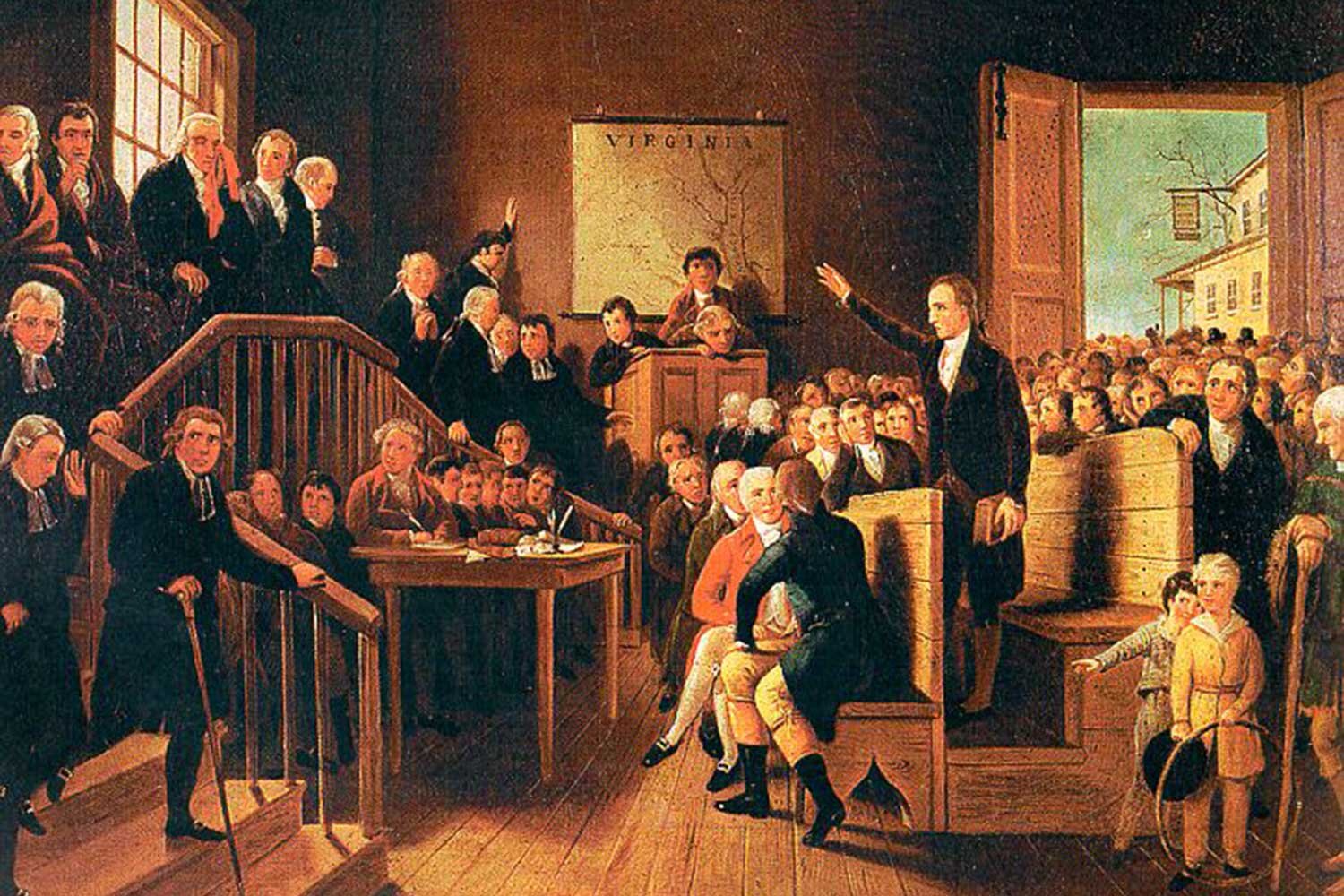

In 1775, as war clouds were rising on the horizon, Thomas, who was a member of Virginia’s House of Burgesses, returned home from the session at which Patrick Henry gave his famous “give me liberty or give me death” speech. He relayed Henry’s oration to his oldest son whose patriotism was fired by the inspirational words. Shortly after fighting broke out at Lexington and Concord, father and son, who had been preparing at home for two years for military service that they knew would come, joined a militia outfit known as the Culpepper Minutemen, Thomas, who had served in the Indian wars, was appointed a Major and John a Lieutenant. Within a few months, Colonel Patrick Henry, the commander of the Virginia militia, called for volunteers to strike back at the aggressive tactics of Royal Governor Lord Dunmore, and, on September 1, 1775, the Culpepper Minutemen mustered at the Culpepper courthouse and headed to Williamsburg.

The fresh Lieutenant who marched off to war was an impressive young man, slightly over six feet tall and slender but wiry strong with raven black hair and eyes that matched. Like Marshall, the men from Culpepper who marched with him had no uniforms but rather wore their frontier trousers made of deer skins and linen hunting shirts dyed brown with leaves, with a bucktail on each hat and a leather belt around their shoulders holding a tomahawk and a scalping knife. Many had Patrick Henry's immortal words “liberty or death” written in large white letters across their breasts. Not surprisingly, to many residents who saw the stalwart militiamen pass in their savage appearance, the men were frightening.

But leaving boyhood and his frontier home behind, John Marshall, at the age of twenty, was about to begin a soldier’s life.

Next week, we will discuss John Marshall, a soldier of the Revolution. Until then, may your motto be “Ducit Amor Patriae,” love of country leads me.

The first few decades of the 19th century were an exciting time for the American judiciary, at least as exciting as anything involving attorneys and judges can be. From the time Thomas Jefferson was sworn in as President on March 4, 1801, through the presidency of Andrew Jackson, there was a tremendous antagonism between the populist Executive branch and the Supreme Court, the last bastion of Federalism. This unprecedented tension between the Executive and the Judiciary made for frequent and intense conflicts, arguably more frequent and more intense than during any other period in our country’s history.