American Judiciary, Part 6: The Nationalist from Virginia

John Marshall's active service in the Continental Army ended in December 1779, although he did not officially retire from the military until February 1781. Marshall went home to Virginia to await his next command, anxious to get back into the fight, but that call never came as the war in the north wound down. Marshall began to think of life after the army and his mind soon turned towards the profession of law but also to romance.

Soon after returning home, Marshall attended a ball in Yorktown hosted by his father Colonel Thomas Marshall. And it was here John met his future wife, Mary “Polly” Ambler, the youngest child of Jacquelin Ambler, who had been one of Yorktown’s wealthiest men before the war. Although Marshall had no money, his natural charm and good nature won Polly's heart. In January 1783, the two were married and spent forty-eight happy years together; they had ten children, six of whom survived to adulthood.

In the spring of 1780, Marshall moved to Williamsburg, roughly twelve miles from Yorktown, and enrolled in the College of William and Mary, in part so he could see Polly, but also to attend the law lectures of George Wythe, considered the most brilliant legal mind in America. But Marshall’s time in Wythe’s lecture hall lasted for only six weeks before love conquered schooling as Marshall left Williamsburg for Richmond when Polly’s father took a position there as the state treasurer.

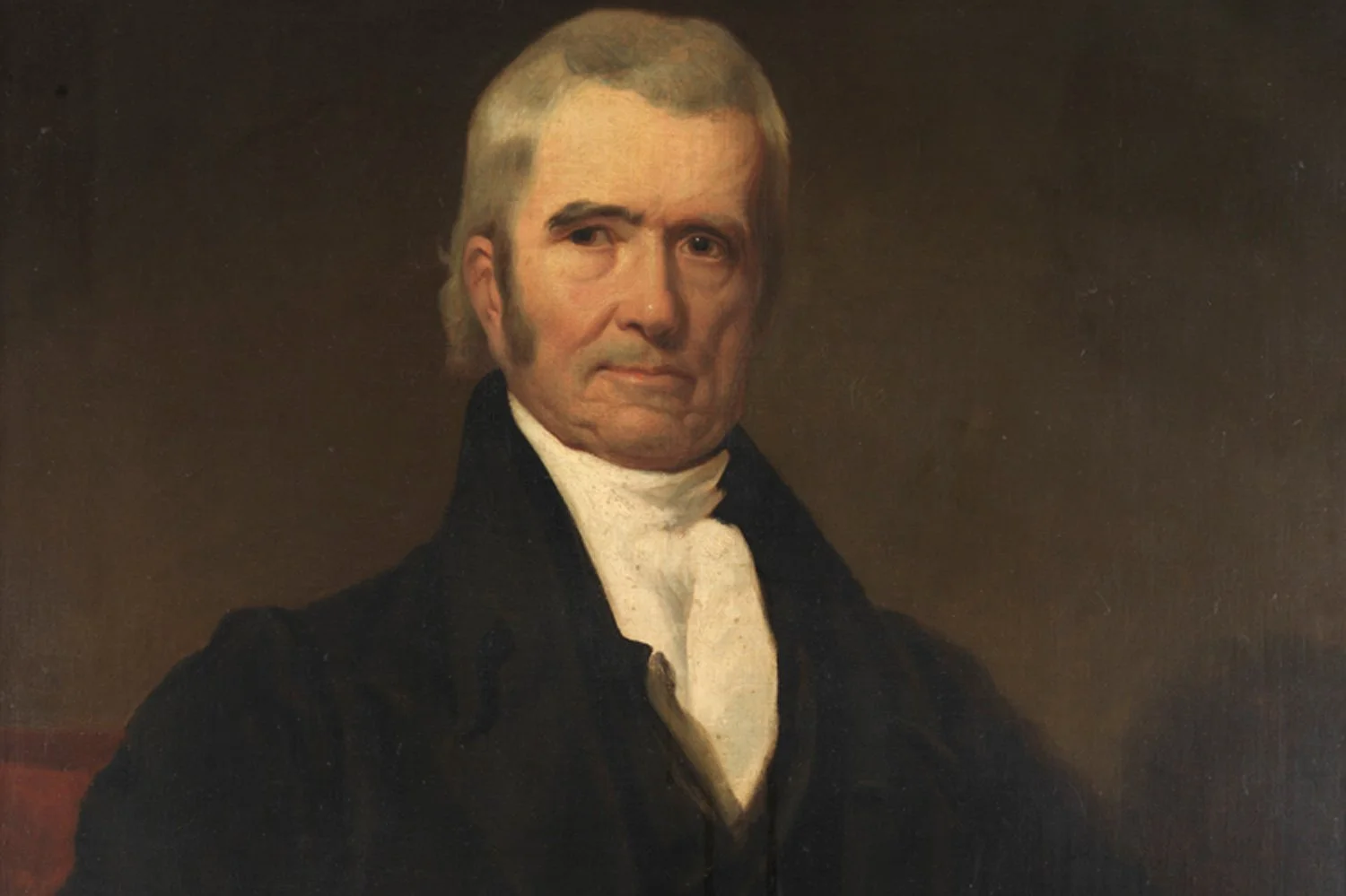

Thus, the man who was destined to be arguably the greatest Supreme Court Chief Justice in our nation's history, certainly the longest serving, the man who established the federal judiciary as a coequal branch of government, spent less than two months in law school. Astonishingly, everything else that Marshall learned regarding legal theories, precedents, and doctrines, he learned on his own and the brilliant decisions that he rendered for the nation essentially were developed by his fertile mind and shaped by his life experiences.

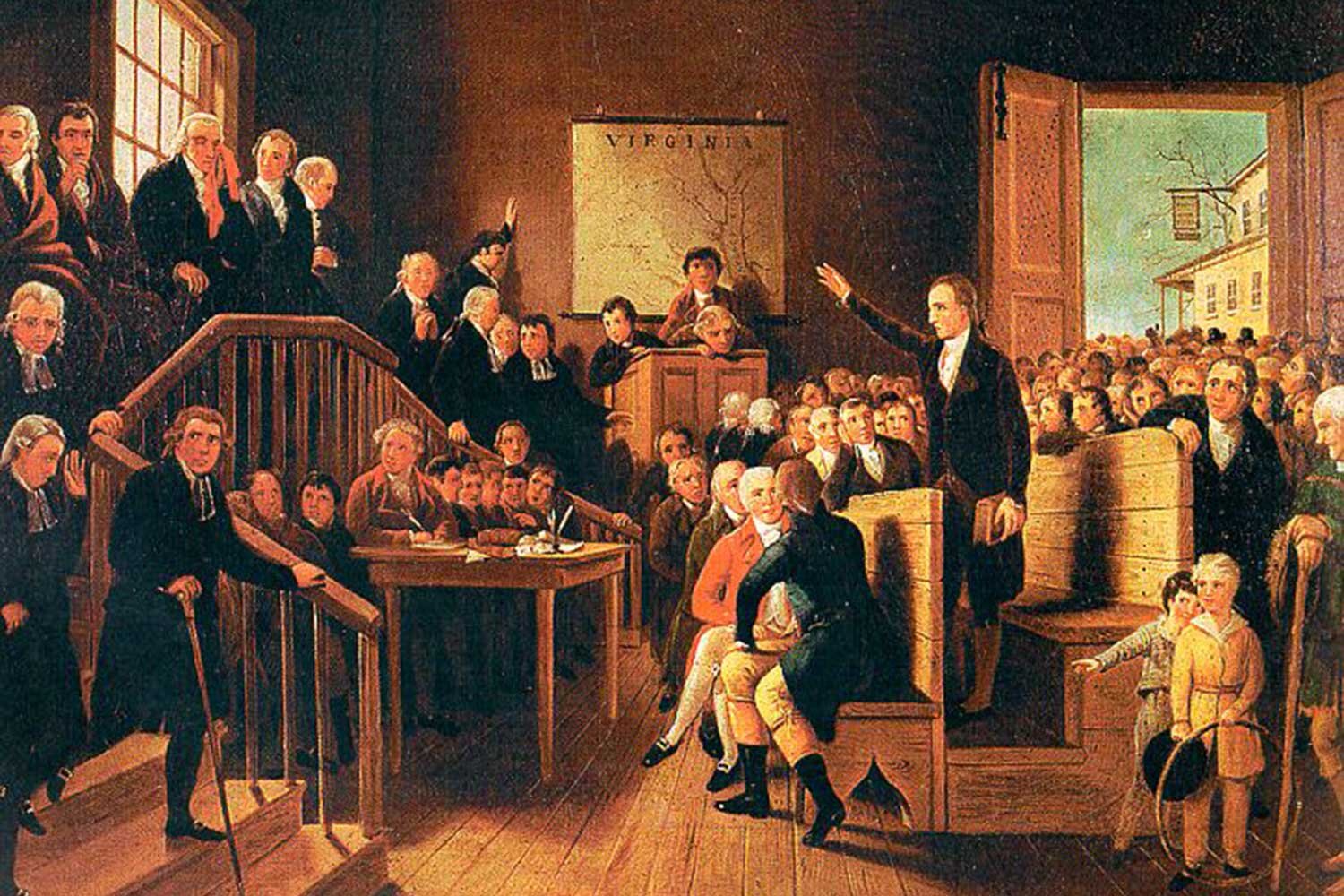

Marshall was granted a license to practice law on August 28, 1780, and, ironically, that license was signed by then Governor Thomas Jefferson, his future nemesis. Being in Richmond and the son-in-law of the state treasurer was a great boost to his fledgling law career and soon cases came Marshall’s way as his intelligence and charm soon won many admirers. By the late 1780s, Marshall was established as one of the finest attorneys in Richmond and was elected to the Virginia House of Burgesses, aligning himself with the leading conservatives in the state. As the need for a stronger national government became more apparent, Marshall became one of the leading advocates for a revision to the Articles of Confederation. Not surprisingly, when the new Constitution was presented to the states for their approval, Marshall helped lead the fight in Virginia. At the state’s ratifying convention in June 1788, Marshall and others like James Madison, along with the unspoken but understood support of George Washington who was not in attendance, overcame strong opposition led by Patrick Henry to get the Constitution approved by a vote of 89 to 79.

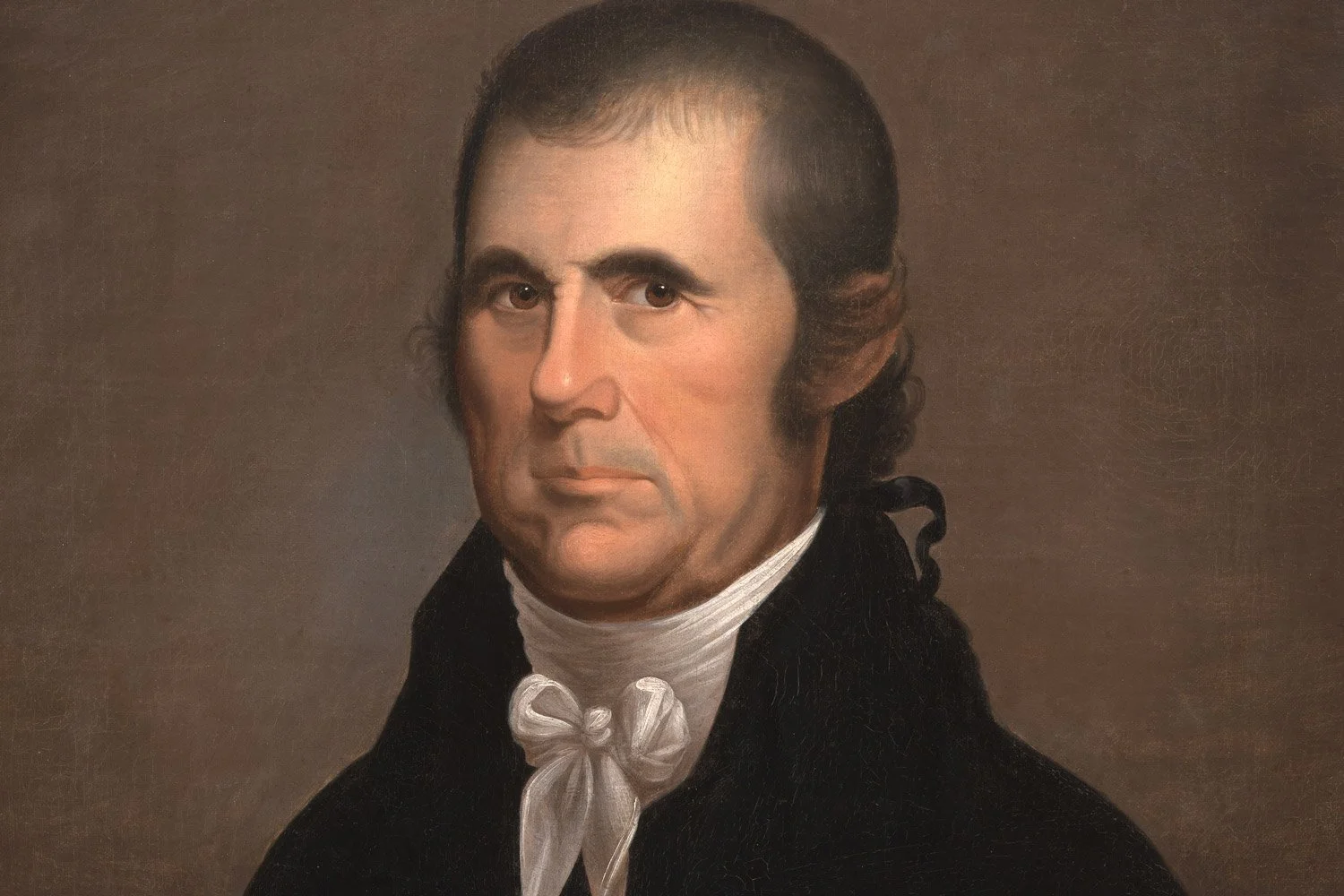

“Patrick Henry.” National Portrait Gallery, Smithsonian Institution.

Soon after Washington became President, he offered Marshall the position of United States Attorney for Virginia which Marshall politely declined knowing that his private law practice would be more lucrative than a government position. And again in 1795, fully recognizing Marshall’s talents, Washington offered Marshall a chance to join his cabinet as the United States Attorney General, but Marshall declined this honor as well. Regardless, Marshall was viewed as one of the leading nationalists in Virginia, a state that was more and more leaning away from the national government under the states’ rights advocacy of Thomas Jefferson.

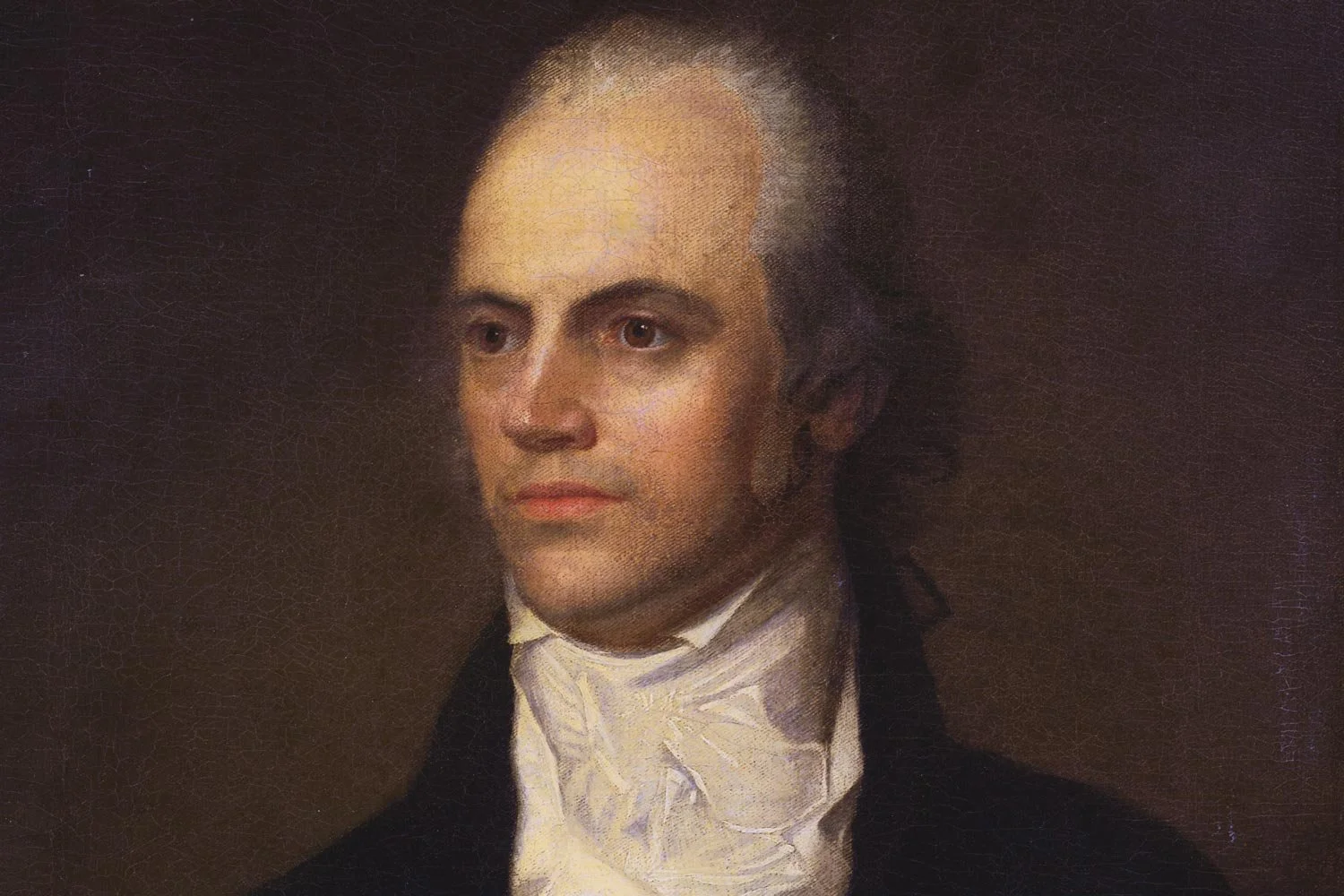

In 1797, as President John Adams tried desperately to keep the peace with France, the President sent a delegation to France to settle differences. The diplomatic team consisted of John Marshall, Charles Coatsworth Pinckney, two staunch Federalists, and Elbridge Gerry, a Democratic-Republican. The American ambassadors arrived in France in October, but were rudely treated by French officials, especially Foreign Minister Charles Maurice Talleyrand who refused to meet with the American delegation until he received significant bribes and a loan guarantee from the United States. Marshall and Pinckney were incensed and refused the bribe demands and soon returned home (Gerry remained behind). Marshall’s dispatches relating the ugly details of this episode, known to history as the XYZ affair, arrived in the spring of 1798 and caused quite a scandal, turning most Americans against France.

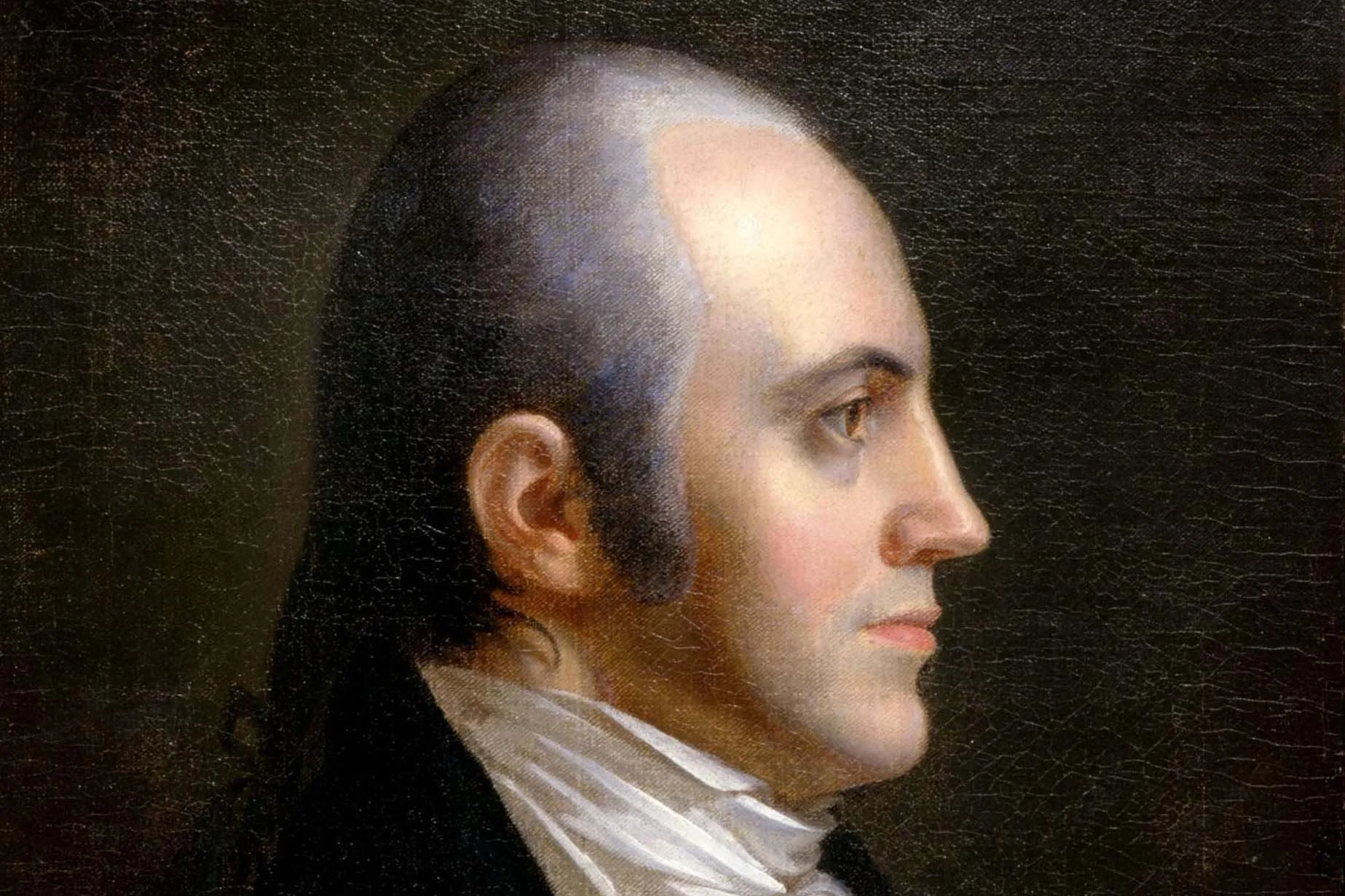

The Federalists saw an opportunity to capitalize on their newfound popularity, but as politicians so often do, they went too far in their response. That summer, they passed a series of laws called the Alien and Sedition Acts, of which the Sedition Act was the most controversial. That legislation made it a crime to criticize the Adams administration, a clear violation of the First Amendments rights of freedom of the press and freedom of speech. From this regrettable act, arose Jefferson’s Kentucky resolution (and James Madison’s corresponding Virginia resolution) which asserted that if states found a federal law to be unconstitutional, the states could declare the law void and therefore not be compelled to follow it. Jefferson’s legal premise was at odds with the doctrine of federal legislative supremacy espoused in Article V of the Constitution and would be addressed by the Supreme Court in 1803.

In 1799, Marshall, an open supporter of Federalist policies, ran for a seat in the United States House of Representatives representing the Richmond area, a district that was a Democratic-Republican stronghold. But such was the respect Marshall enjoyed from those that knew him that he easily won the election. Marshall served just one term before leaving office to become Secretary of State for President Adams, serving in this capacity until the end of the Adams administration on March 4, 1801.

But prior to leaving office, President Adams named Marshall as the 4th Chief Justice of the Supreme Court. Adams would later state that “my gift of John Marshall to the people of the United States was the proudest act of my life.” And proof of the soundness of that decision would come two years later in the consequential case of Marbury v Madison.

Next week, we will discuss the Supreme Court case of Marbury v Madison. Until then, may your motto be “Ducit Amor Patriae,” love of country leads me.

The first few decades of the 19th century were an exciting time for the American judiciary, at least as exciting as anything involving attorneys and judges can be. From the time Thomas Jefferson was sworn in as President on March 4, 1801, through the presidency of Andrew Jackson, there was a tremendous antagonism between the populist Executive branch and the Supreme Court, the last bastion of Federalism. This unprecedented tension between the Executive and the Judiciary made for frequent and intense conflicts, arguably more frequent and more intense than during any other period in our country’s history.