Lewis and Clark Expedition, Part 10: Homeward Bound

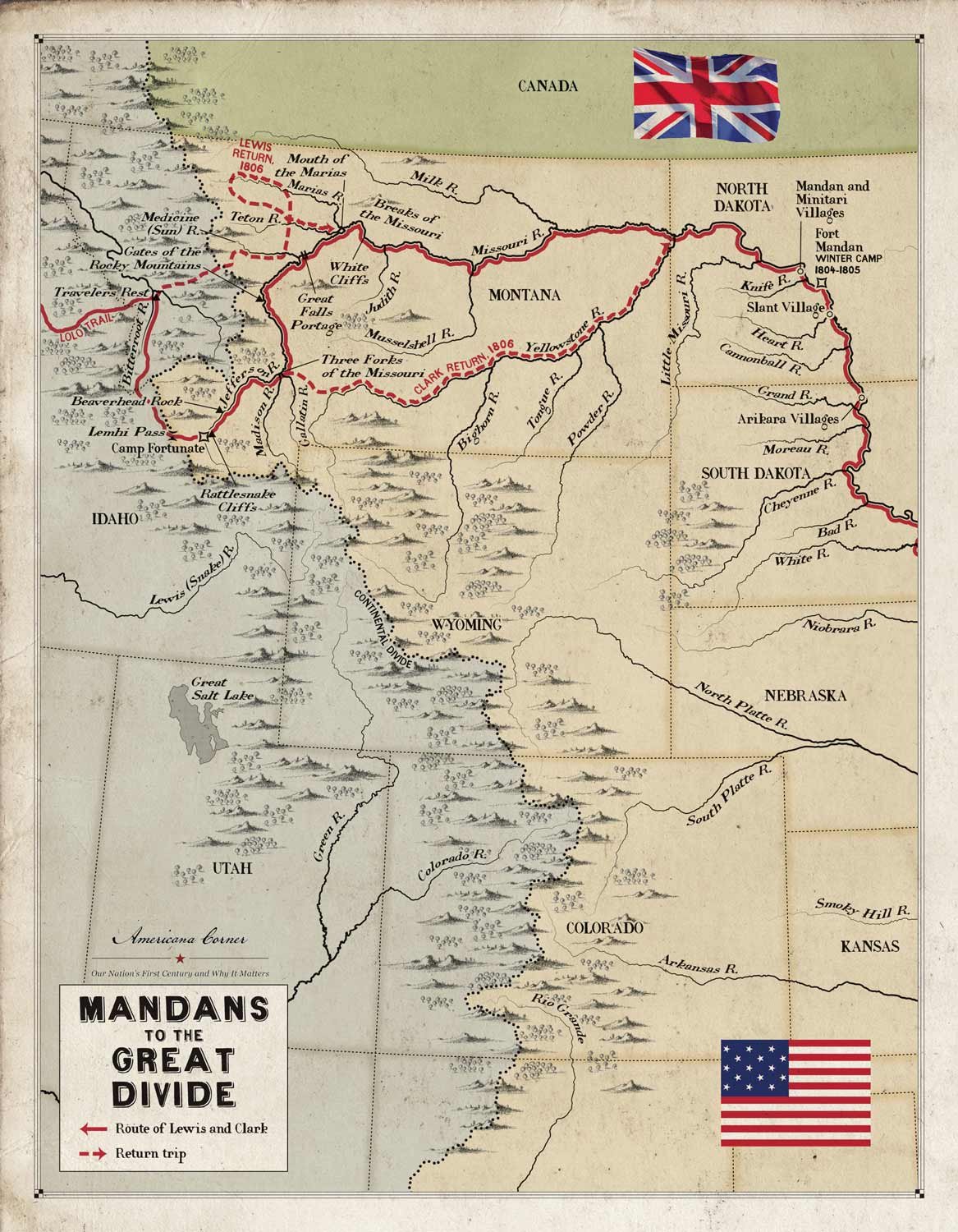

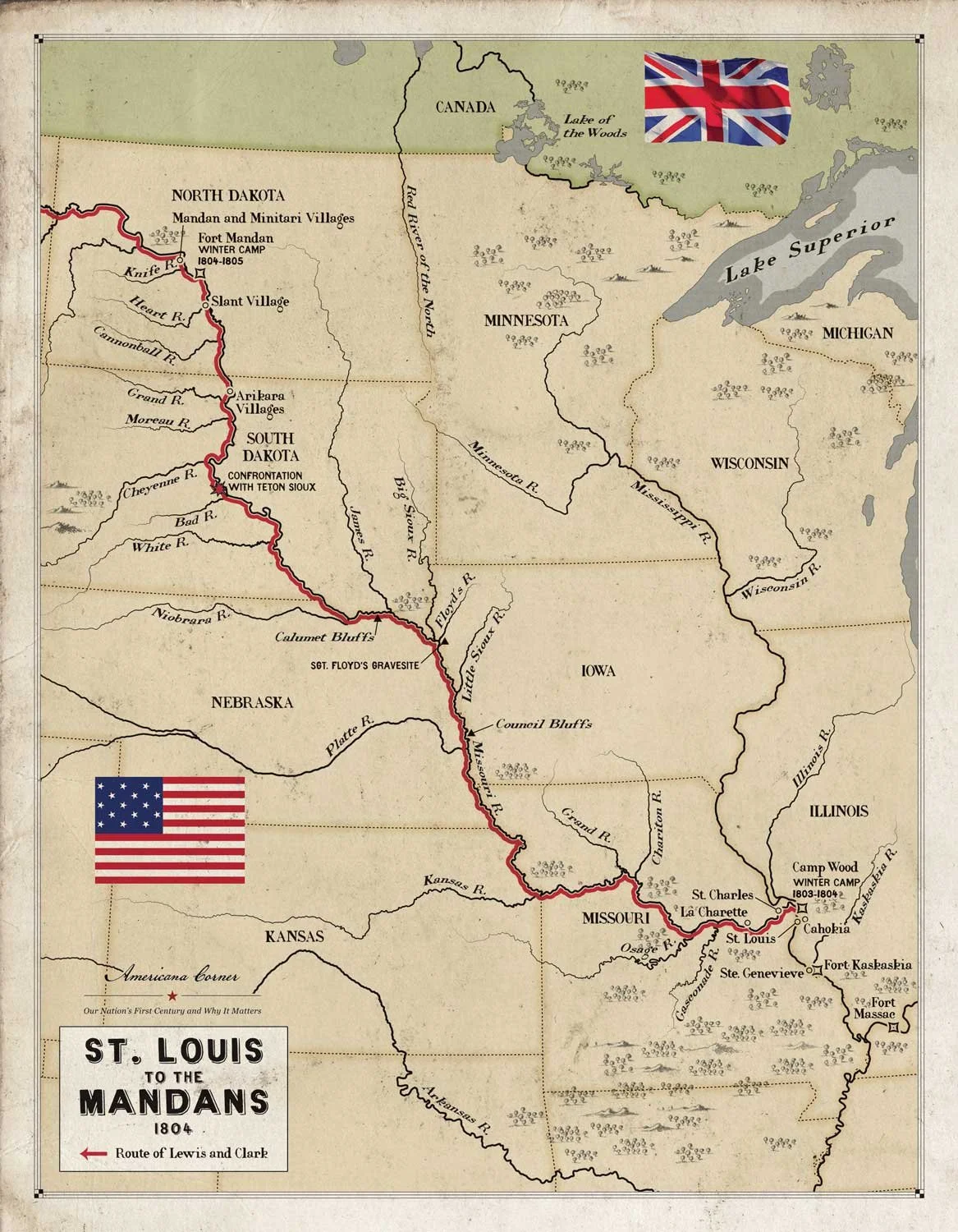

Captains Meriwether Lewis and William Clark had guided the Corps of Discovery four thousand miles to the Pacific Ocean, and they planned to continue their explorations on the return leg of their journey. The plan was to temporarily split up the Corps with Clark taking one group to descend and explore the Yellowstone to its junction with the Missouri, Sergeant Ordway leading another party to the Falls of the Missouri and there make preparations to portage the Falls, while Lewis was to lead a third group up the Marias River and determine its northern most latitude to further establish the boundaries of the Louisiana Purchase. They would all reunite at the mouth of the Yellowstone River in about six weeks. Their plan was both ambitious and risky in that they were splitting the Corps into small groups while passing through potentially hostile territory, especially the Blackfoot and Crow nations. But the Captains knew their mission was to gather as much information as possible for President Jefferson and so, with faith in themselves and the men they had trained for two years, they took this calculated risk to divide the party.

Lewis had arguably the most dangerous job in that he was going deep into Blackfoot territory with only three other men to explore the headwaters of the Marias. Lewis traveled along its banks until July 22, 1806, before starting back towards the rendezvous with Clark but had the misfortune of coming across a party of eight Blackfoot warriors, part of a larger band one day’s march away. The Blackfoot and the Americans camped together that night and, just before dawn, the Blackfoot tried to steal the American’s rifles. In the struggle that ensued, two Blackfoot were killed and the others fled back to alert the main camp. Although none of Lewis’s men were injured, they were now more than 200 miles from the rest of the Corps, with a band of vengeance-minded warriors probably headed their way. Lewis knew they were in a tight spot, and they immediately set out at a trot towards the Missouri, riding all day long, only stopping once to rest the horses before mounting up and continuing until two in the morning, when Lewis finally ordered a halt; they had covered 100 miles. They started again at first light and by noon Lewis and his men were at the Missouri where found the welcomed sight of Sergeant Ordway’s detachment waiting for them.

Charles Marion Russell. “Lewis and Clark Meeting the Mandan Indians.” Wikiart.

The reunited group headed downriver, reaching the mouth of the Yellowstone River on August 7 where they found a note from Clark saying that he had moved on to find a better location along the Missouri and Lewis and his party followed. Unfortunately for Captain Lewis, two days later, while out hunting with a near-sighted private named Cruzatte, the Private mistook Lewis, dressed in buckskin, for an elk and shot him in the buttocks. The bullet passed clean through without hitting any bone, but it was terribly painful, and Lewis was forced to continue downriver lying on his belly in the canoe. On August 12, Lewis and his men finally met up with Clark, who had had his own misfortunes, losing most of the Corps remaining horses to a band of Crow Indians, acknowledged as the best horse-thieves on the Great Plains. But most importantly, the Corps was reunited at last and in the home stretch of the expedition.

They soon arrived at the Mandan villages where they had spent the long winter of 1804-1805 and said goodbye to Charbonneau and Sacagawea, the brave Shoshone woman who had been such a help to the expedition. The canoes were now flying along and between the strong current of the Missouri and an even stronger desire to get home, the men were averaging almost eighty miles a day. As the expedition headed downriver, they began to encounter trappers heading the other way towards the mountains and the rivers the Corps had just explored, and familiar landmarks came one after another, the Platte River marking the end of the Great Plains on September 9 and, less than a week later, they crossed the mouth of the Kansas River. The first of the settlements, La Charette and St. Charles, were soon reached and, finally, on September 23, the men of the Corps of Discovery paddled their canoes into the Mississippi and landed at St. Louis, their journey now at an end; mission accomplished!

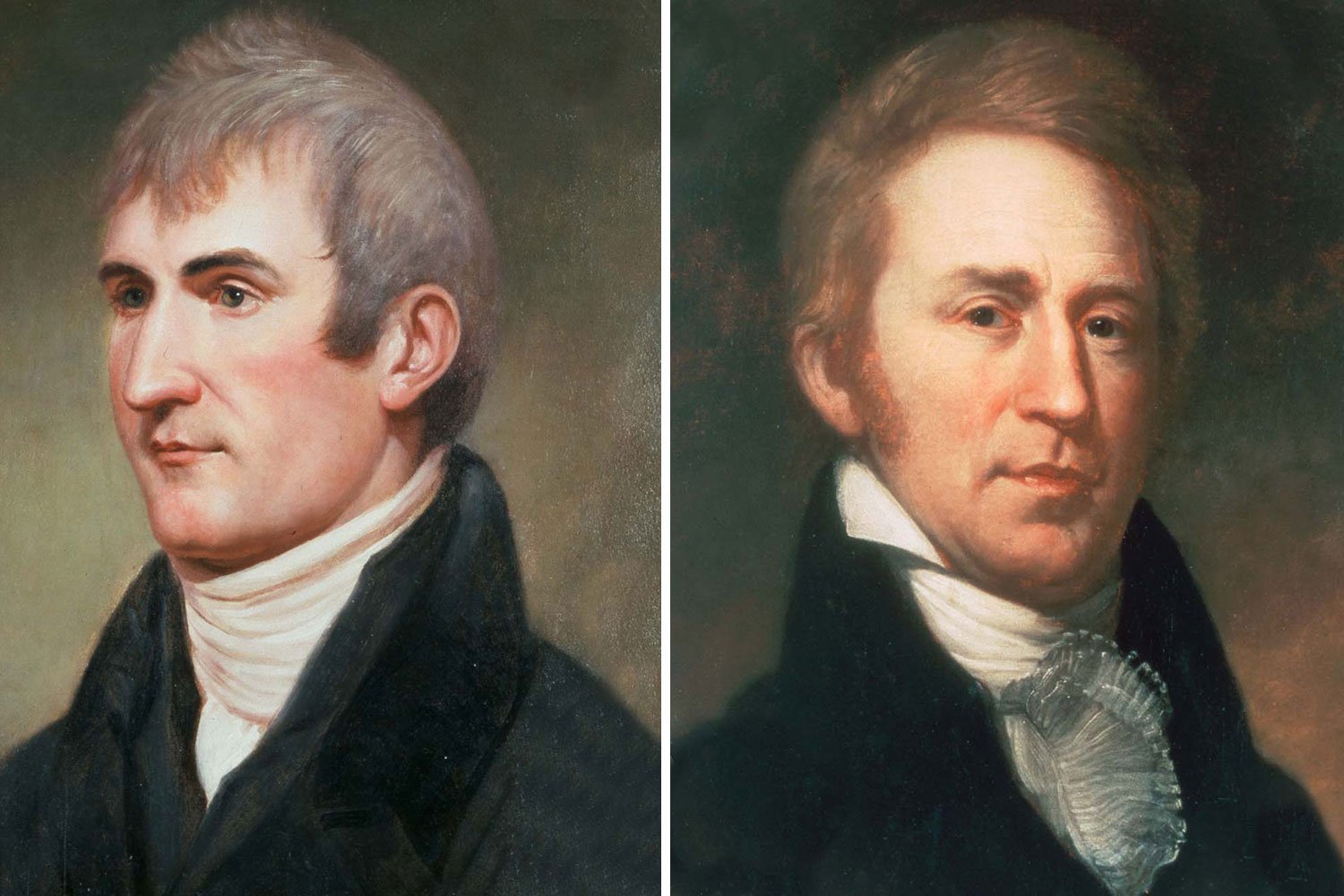

And with that end the Lewis and Clark expedition passed into the pantheon of American heroes and legends. Looking back to their world of 1803 and given the limited knowledge of the land they would cross and the seemingly sparce assets they would have to make that crossing, Lewis and Clark’s accomplishments are beyond extraordinary, almost unfathomable. Meriwether Lewis and William Clark had taken thirty men, mostly civilians, and somehow molded them into a fine-tuned, cohesive military unit that had faced every hardship and overcome every obstacle using just their innate skills and faith in each other to complete what was undoubtedly the greatest expedition in American history.

The Corps of Discovery had traveled more than 8,000 miles over the course of twenty-eight months, making their way by keelboat, canoes, and horses as the need arose and circumstances permitted, and in doing so traversed a Garden of Eden that would vanish forever with the speed of American expansionism. They had found the headwaters of the Missouri and confirmed the extent of the watershed of that great river and settled once and for all that there was no all-water route across the continent and, importantly, that the portage between the navigable portions of the Missouri and the Columbia was both long at 340 miles and formidable as they confirmed that the Rockies were not a single chain of mountains but rather an entire series. Additionally, the detailed maps created by Captain Clark of the trans-Mississippi region gave a clearer picture of the vast lands the country had recently acquired in the Louisiana Purchase.

But perhaps most significantly, Lewis and Clark had inspired other Americans to follow in their wake and in doing so impelled the nation forward to conquer the continent.

Next week we mark a major milestone—the release of our 250th article at Americana Corner! Our new series will highlight America’s first foreign war, the Barbary Wars, a defining chapter in our early republic’s emergence on the world stage. Until then, may your motto be “Ducit Amor Patriae,” love of country leads me.

Captains Meriwether Lewis and William Clark had guided the Corps of Discovery four thousand miles to the Pacific Ocean, and they planned to continue their explorations on the return leg of their journey. The plan was to temporarily split up the Corps with Clark taking one group to descend and explore the Yellowstone to its junction with the Missouri, Sergeant Ordway leading another party to the Falls of the Missouri and there make preparations to portage the Falls, while Lewis was to lead a third group up the Marias River and determine its northern most latitude to further establish the boundaries of the Louisiana Purchase.