Lewis and Clark Expedition, Part 9: Wintering at Fort Clatsop

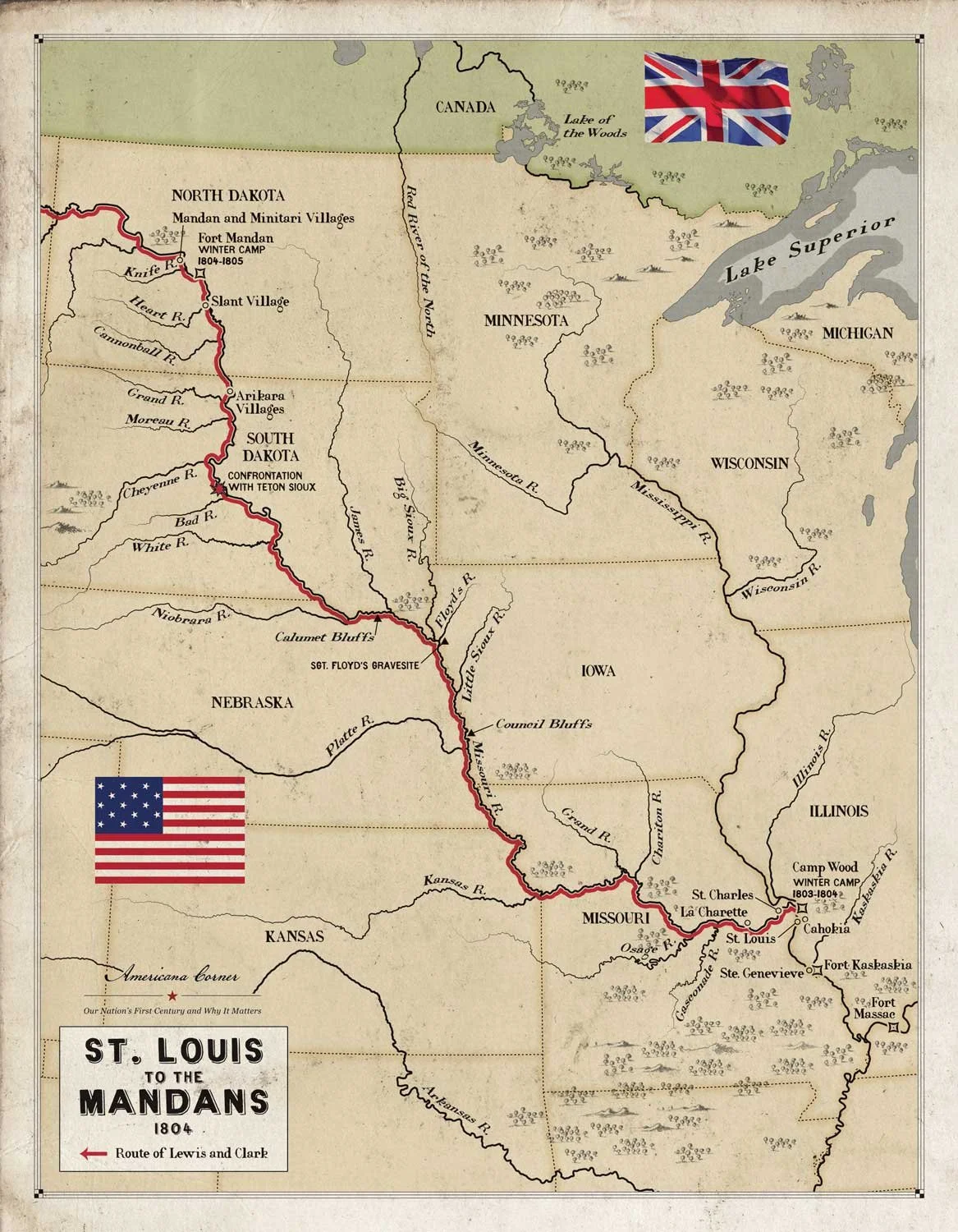

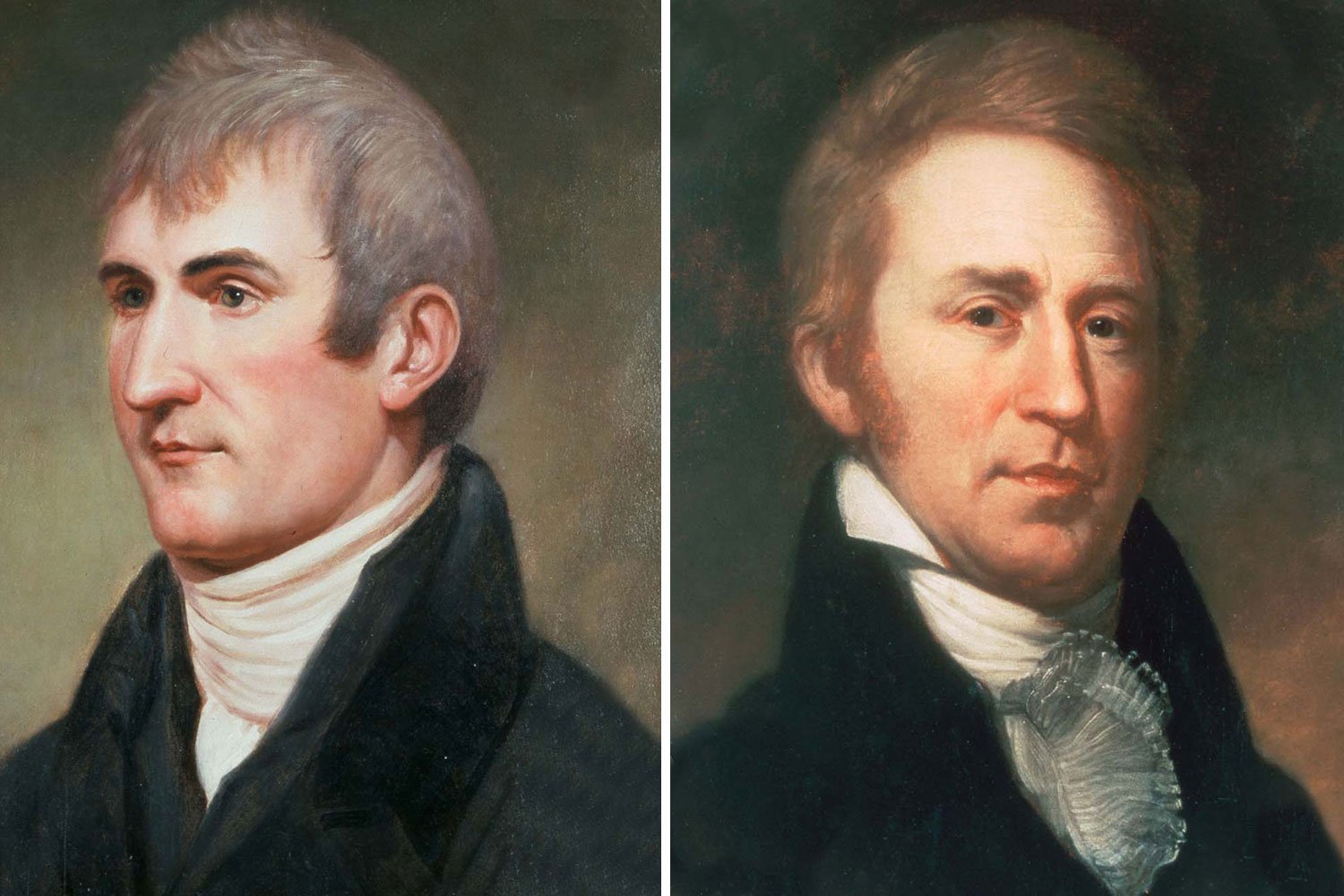

The Lewis and Clark Expedition sighted the Pacific Ocean, or more specifically the Columbia River estuary, on November 7, 1805, and spent the next month exploring the area and searching for a suitable location to build a fort for the coming winter. It was a wretched month, one of the worst of the entire journey, as the constant rain soaked the men and their equipment. But despite the conditions, the men felt a growing sense of pride as they considered their incredible accomplishments since leaving St. Louis in May 1804. Captain Clark found a large pine tree near the coast and carved his mark for posterity, “William Clark December 3rd 1805. By land from the U.States in 1804 & 1805.”

Captain Lewis finally decided to set up camp on a small bluff overlooking today’s Lewis and Clark River, roughly three miles upstream from the Columbia. It was here that the Corps erected Fort Clatsop and spent their final winter away from home. Unfortunately, between the troublesome local Indians, miserable weather, and a monotonous diet, it would prove to be a most unpleasant three months. The Corps had long since left the lands of the Nez Perce who had befriended the Americans and entered those dominated by the Chinook, a people who seemed almost antagonistic to them. The men learned the hard way that this nation of Indians would steal anything they could if the soldiers were not looking. Naturally, this theft led to hard feelings and the men learned to mistrust and even detest the Indians of the lower Columbia, and no Indians were permitted to remain inside the fort overnight. Consequently, the Captains made little effort to engage with the Chinook, even though their assistance was critical to establishing a good trade network along the Pacific Coast.

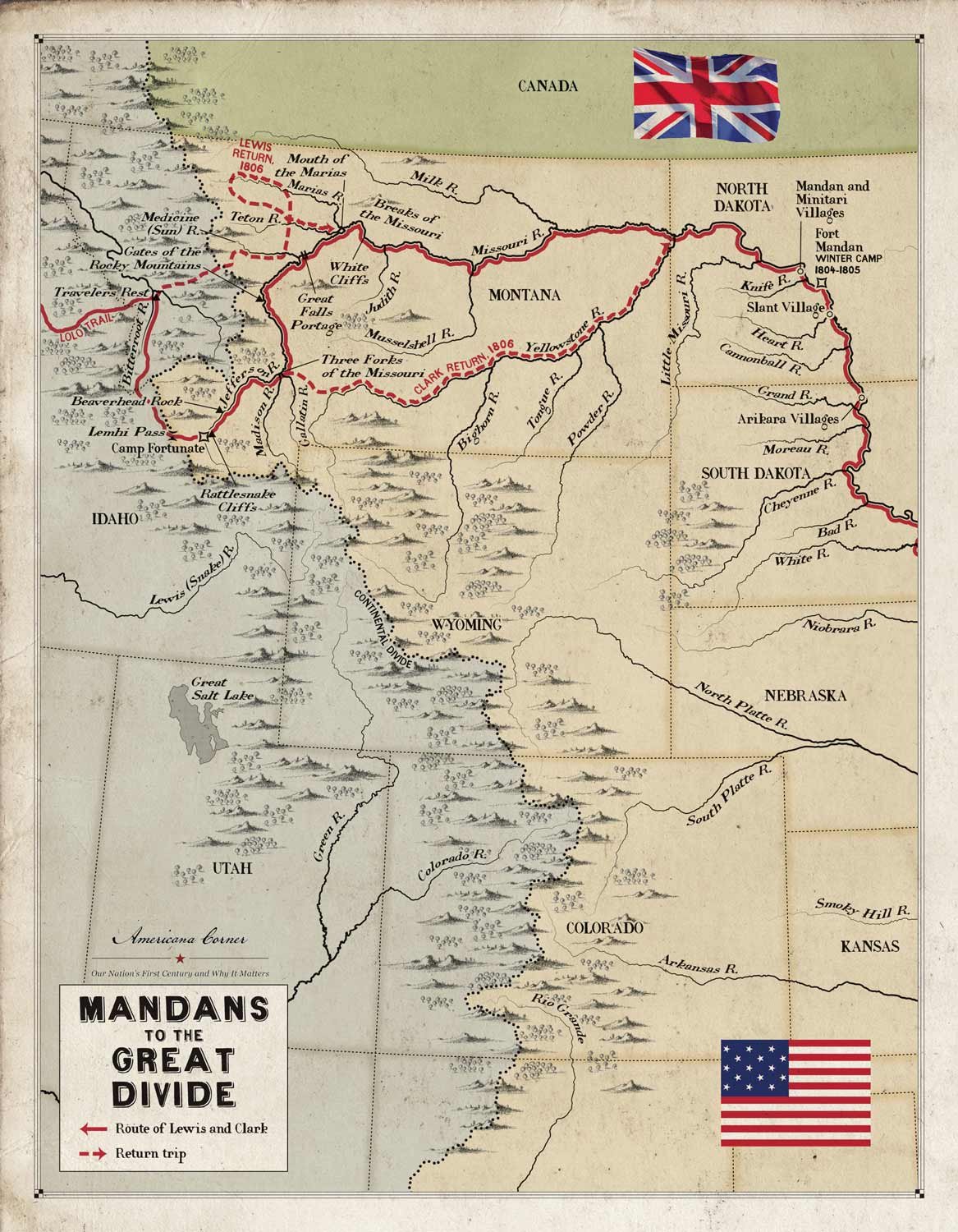

“Great Divide to the Pacific.” Americana Corner.

The weather was also intolerable to the men of the Corps, largely comprised of Virginians and Kentuckians raised in the Appalachian Mountains. During their one hundred days at Fort Clatsop, it rained every day but eight and both equipment and clothing rotted, not surprising given that the Pacific Northwest is the largest temperate rainforest in the world. Food options were also not to their liking as big game animals were scarce except for elk near the mouth of the river. On the upper river, the diet had been berries, roots, and some dried salmon, while near the mouth of the Columbia it was elk, elk, and more elk: grilled, boiled, jerked and in soups. Unhappiness with the locals, food, and the environment contributed to a shortened stay at Fort Clatsop. While the Corps spent almost six months at their first two winter encampments, Camp Wood and Fort Mandan, they remained at Fort Clatsop for only a little over three months.

During the winter, the captains had time to reflect on what they had achieved thus far on their journey. The primary mission of the Corps of Discovery as designed by President Jefferson was to find the most practical commercial route from St. Louis to the Pacific Ocean, hopefully one that comprised mostly water (Missouri and Columbia rivers) and a short portage over the Continental Divide. They had been disappointed to discover that the portage between the navigable portions of the Missouri and the Columbia was more than three hundred miles across some of the most formidable mountains on the continent. But more importantly, they had at last established certainty on this matter and from that knowledge the President could build his plans for a viable commercial trade system.

And to create that system, it was essential that Lewis and Clark establish good relations with the Indians along the Missouri River, through the Rockies where the portage would cross, and in the Columbia River basin, an aspect of the expedition that had seen mixed results. The captains had made great inroads with the Mandans during the winter of 1804-05 and their relations with the Shoshone and Nez Perce were strong. However, the Sioux on the first leg of the journey had been intractable and unresponsive to the captains calls for peace and improved trade relations with the United States. In fact, Lewis and Clark would discover upon their return that most of the tribes above the Platte River were once again at war with one another. Meanwhile the Chinook, the strongest tribe of the lower Columbia, seemed uninterested in engaging the Americans who the Natives viewed as a threat to their growing dominance with European and American trading ships. Moreover, they had not yet encountered the Blackfoot and Crow, the two most powerful tribes along the upper Missouri; they were also considered the most dangerous tribes as the Corps would find out on their return journey. The captains were discovering that the ancient animosities of the Indian nations died hard and could not be extinguished with a few trinkets and seemingly unrealistic promises of peace and protection from the Great Father back east.

By early March 1806, the Captains and the men had had enough of Fort Clatsop and began to prepare for the long journey home. Lewis ensured the Corps had adequate supplies, especially ammunition and gunpowder, noting they were their “only hope for subsistence and defence in a rout of 4000 miles through a country exclusively inhabited by savages.” On March 23, the men departed from the fort to begin their long journey home, moving upstream against the strong current of the Columbia. Rather than portage around the rapids of the Columbia and to get away from the Chinook, who continued to harass the Americans at each campsite, the expedition abandoned their canoes and headed overland on April 24. By early May, the Corps was back at the Nez Perce villages where they obtained badly needed horses and spent a month waiting for the snow in the Bitterroot Mountains to melt. After one abortive attempt to cross the Bitterroots in mid-June, the Corps, with the help of expert Nez Perce guides, finally reached their former camp of Traveler’s Rest, covering the 160 miles in only six days, about half the time required the year before. Three days later, the Corps began their final push for home.

Next week, we will discuss the homeward journey of the Corps of Discovery. Until then, may your motto be “Ducit Amor Patriae,” love of country leads me.

Captains Meriwether Lewis and William Clark had guided the Corps of Discovery four thousand miles to the Pacific Ocean, and they planned to continue their explorations on the return leg of their journey. The plan was to temporarily split up the Corps with Clark taking one group to descend and explore the Yellowstone to its junction with the Missouri, Sergeant Ordway leading another party to the Falls of the Missouri and there make preparations to portage the Falls, while Lewis was to lead a third group up the Marias River and determine its northern most latitude to further establish the boundaries of the Louisiana Purchase.