Lewis and Clark Expedition, Part 4: Lewis and Clark Leave Civilization Behind

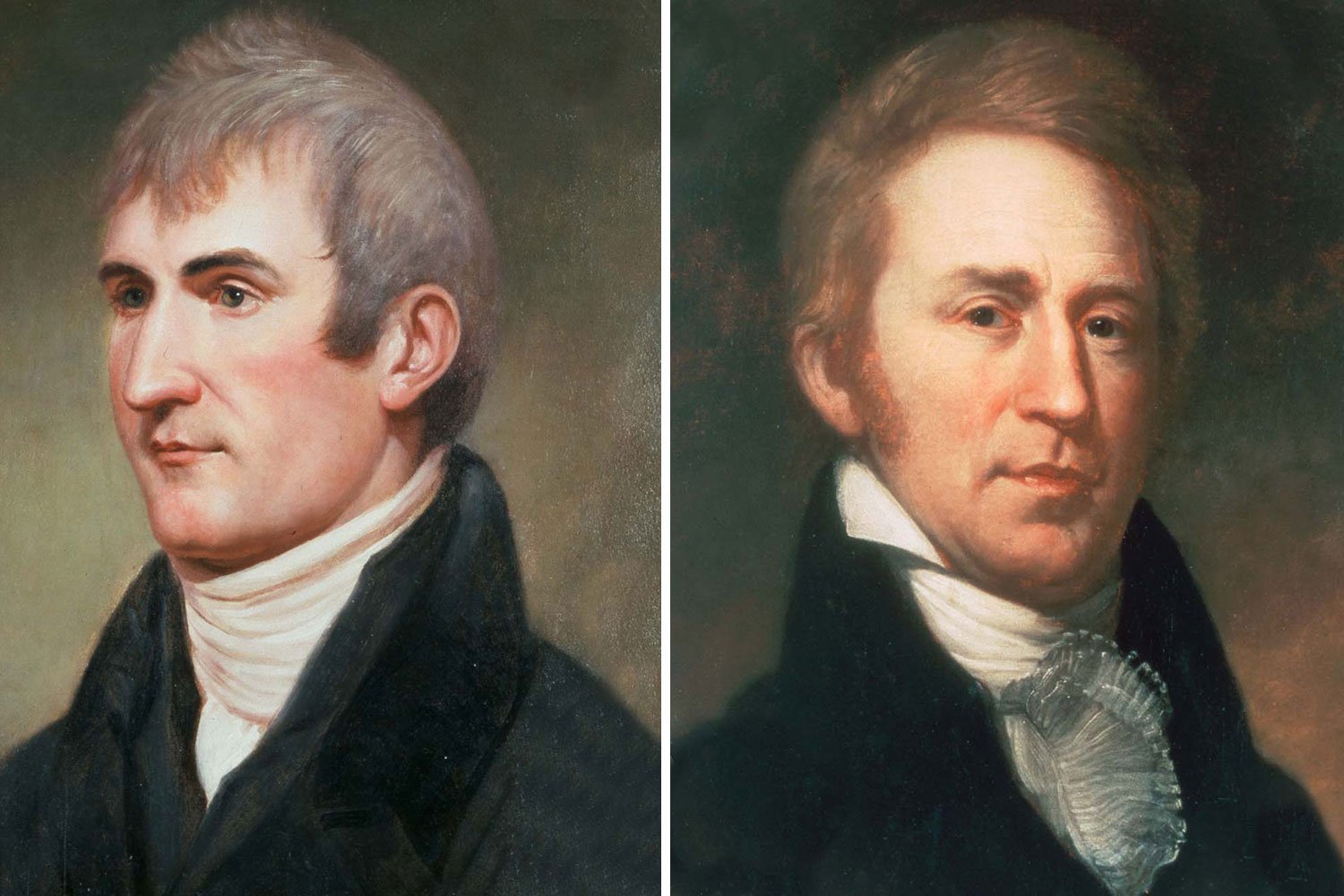

On August 31, 1803, Captain Meriwether Lewis departed from Fort Fayette, today’s Pittsburgh, in the keelboat the Corps of Discovery would take up the Missouri River and, six weeks later, arrived at the Falls of the Ohio and Clarksville, Indiana Territory. It was here, at the town founded by General George Rogers Clark, that Meriwether Lewis and William Clark, the General’s youngest brother, met again for the first time in seven years and commenced the most famous partnership in American history, two men so joined in American lore as to almost be inseparable.

They reached the Mississippi in late November and first encountered the challenge they would face the following year of moving the cumbersome keelboat upstream against a strong current. Consequently, the Captains decided to expand their contingent beyond what was originally authorized by Secretary of War Henry Dearborn. When they reached the First Infantry Regiment post at Kaskaskia, they signed on more men, including Sergeant John Ordway, who would be the main non-commissioned officer for the expedition.

Thure de Thulstrup. “Hoisting American Colors, Louisiana Cession, 1803.” Wikimedia.

President Thomas Jefferson had hoped that the Corps of Discovery would be part way up the Missouri in 1803 before winter set in but, between the seemingly endless delays in constructing the keelboat, selecting the right men for the journey, and securing needed supplies, Lewis and Clark did not arrive near St. Louis until early December.

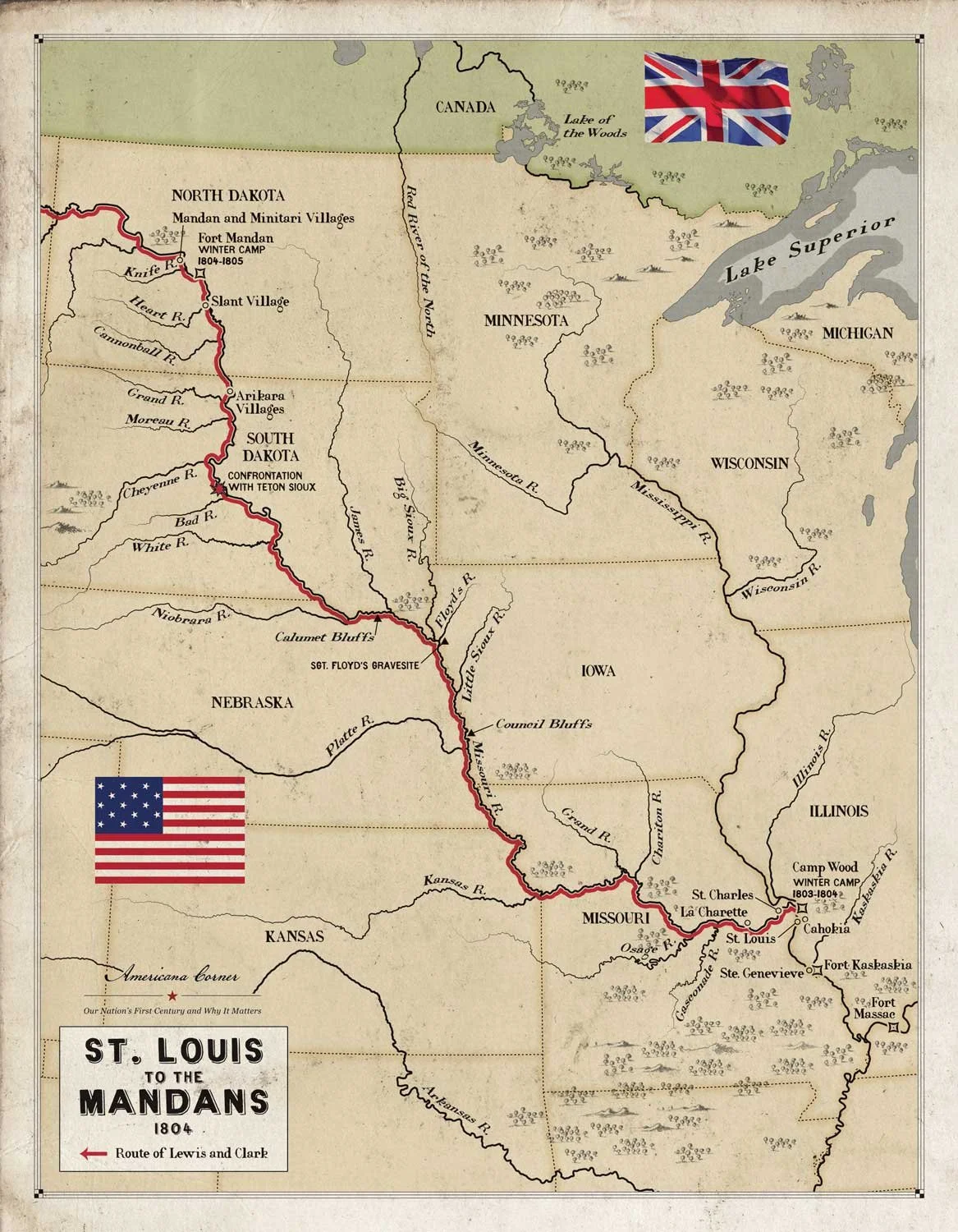

The Corps soon erected Camp Wood on the east bank of the Mississippi just upstream from St. Louis, near present-day Wood River, Illinois, and directly across from the mouth of the Missouri River. Their new plan was to leave once the Missouri was relatively free of ice and attempt to reach the Mandan villages (near present day Bismarck, North Dakota), roughly 1,300 river miles above St. Louis, in the late autumn and spend the winter there before proceeding west. While Lewis further developed his plans and organized supplies for the expedition, Clark continually drilled the men to hone their skills, turning these recent civilians into soldiers.

On March 9, 1804, in a formal service in St. Louis known as the Three Flags Ceremony, the complicated transfer of Upper Louisiana took place (the District of Orleans had transferred on December 20, 1803). First, Spain gave possession of the territory to France which had been agreed upon in the Treaty of Ildefonso. Out of respect for the French citizens of St. Louis, the United States representative, Captain Amos Stoddard, agreed to let the French flag fly all that day. The next morning, France transferred Upper Louisiana to the United States, completing the Louisiana Purchase and clearing the way for Lewis and Clark to proceed. On May 21, the Corps pushed out into the current and as Clark wrote in his journal, “Set out at half passed three oClock under three Cheers from the gentlemen on the bank.” With this launch, the men passed from the realm of the known into that of the unknown, into a world where the only support they would find for the next two years would be from within the Corps.

Although the initial part of the journey was over territory that was fairly well known, it was new to the men of the Corps, and they soaked in one landmark after another. On June 1, they passed the Osage River, and three weeks later, they crossed the mouth of the Kansas River, future home of Kansas City, where the Missouri turns sharply north. On July 21, a full two months after their departure and 600 miles upstream from the Mississippi, the Corps arrived at the Platte River, a wide but shallow river that bisects Nebraska east to west and marked a sort of line of demarcation between the known parts of the lower Missouri River and the unknown parts beyond.

As the Corps moved north, they entered an enchanting land that must have been as God first made it, a paradise that very few would ever see again. They encountered herds of elk in every stand of woods along the river and huge flocks of migratory birds overhead or resting along the banks of the Missouri. As Clark noted, “Great numbers of Buffalow and Elk on the hill…I saw several foxes and killed a Elk and 2 Deer and Squirrels…vast herds of herds of Buffaloe deer Elk and Antilopes were seen feeding in every direction as far as the eye of the observer could reach…Muskeetors verry troublesome;” even Eden had its issues.

But despite the idyllic surroundings, the Corps of Discovery was still an independent military expedition with no outside means of support, and they were reminded of that all too often. On August 20, Sergeant Charles Floyd died from a ruptured appendix far from any professional medical help, the only fatality the Corps experienced during the expedition. The following month, the Corps ran into the troublesome Teton, the largest band of Sioux along the river and considered by trappers and traders as the pirates of the Missouri; Lewis called them “the vilest miscreants of the savage race.”

Over the course of the next four days, tensions reached a fever pitch and on two occasions the small band of Americans stood face-to-face against hundreds of armed warriors ready for a fight. In one instance, the Teton would not allow a small detachment led by Clark to return to the keelboat until they were given gifts. Clark refused their demands and drew his sword while Lewis watching from the keelboat loaded and primed their swivel gun. The Captains held firm but showed restraint and did not give the order to fire despite repeated provocations. Eventually, the Teton backed down which was a new habit for them as they had been used to bullying French and English trappers and always getting their way. Word of this new breed of white man called Americans that would fight rather than submit quickly spread along the Indian’s moccasin highway and may help explain why the Corps rarely encountered any Indians on their journey to the Rockies.

One month later, the Corps approached the Mandan villages, home to the peaceful Mandan nation and the center of trade on the Great Plains, completing the first leg of their journey to the Pacific.

Next week, we will discuss the Corps wintering at Fort Mandan. Until then, may your motto be “Ducit Amor Patriae,” love of country leads me.

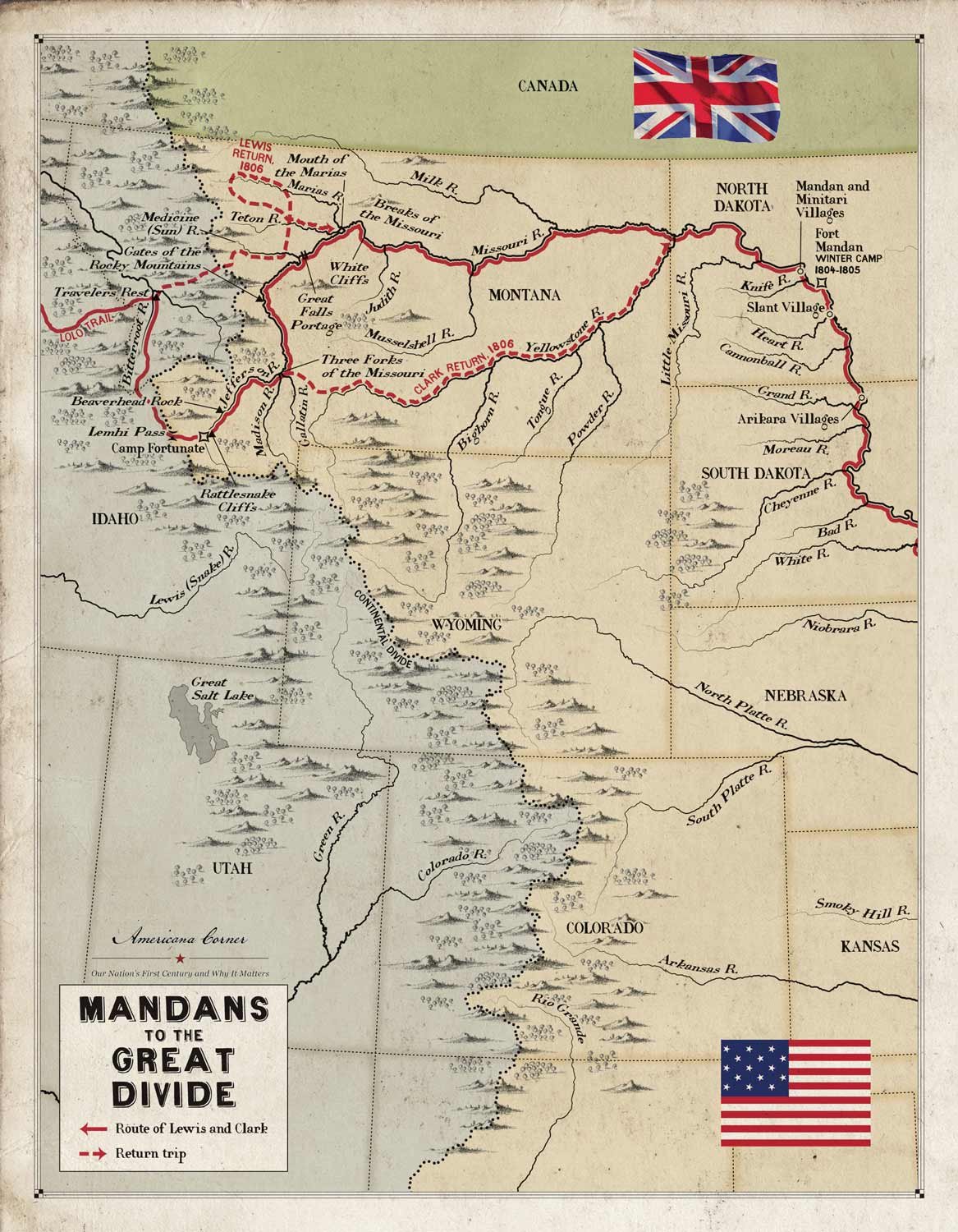

Captains Meriwether Lewis and William Clark had guided the Corps of Discovery four thousand miles to the Pacific Ocean, and they planned to continue their explorations on the return leg of their journey. The plan was to temporarily split up the Corps with Clark taking one group to descend and explore the Yellowstone to its junction with the Missouri, Sergeant Ordway leading another party to the Falls of the Missouri and there make preparations to portage the Falls, while Lewis was to lead a third group up the Marias River and determine its northern most latitude to further establish the boundaries of the Louisiana Purchase.