Lewis and Clark Expedition, Part 8: “Ocian in View! O! the joy!”

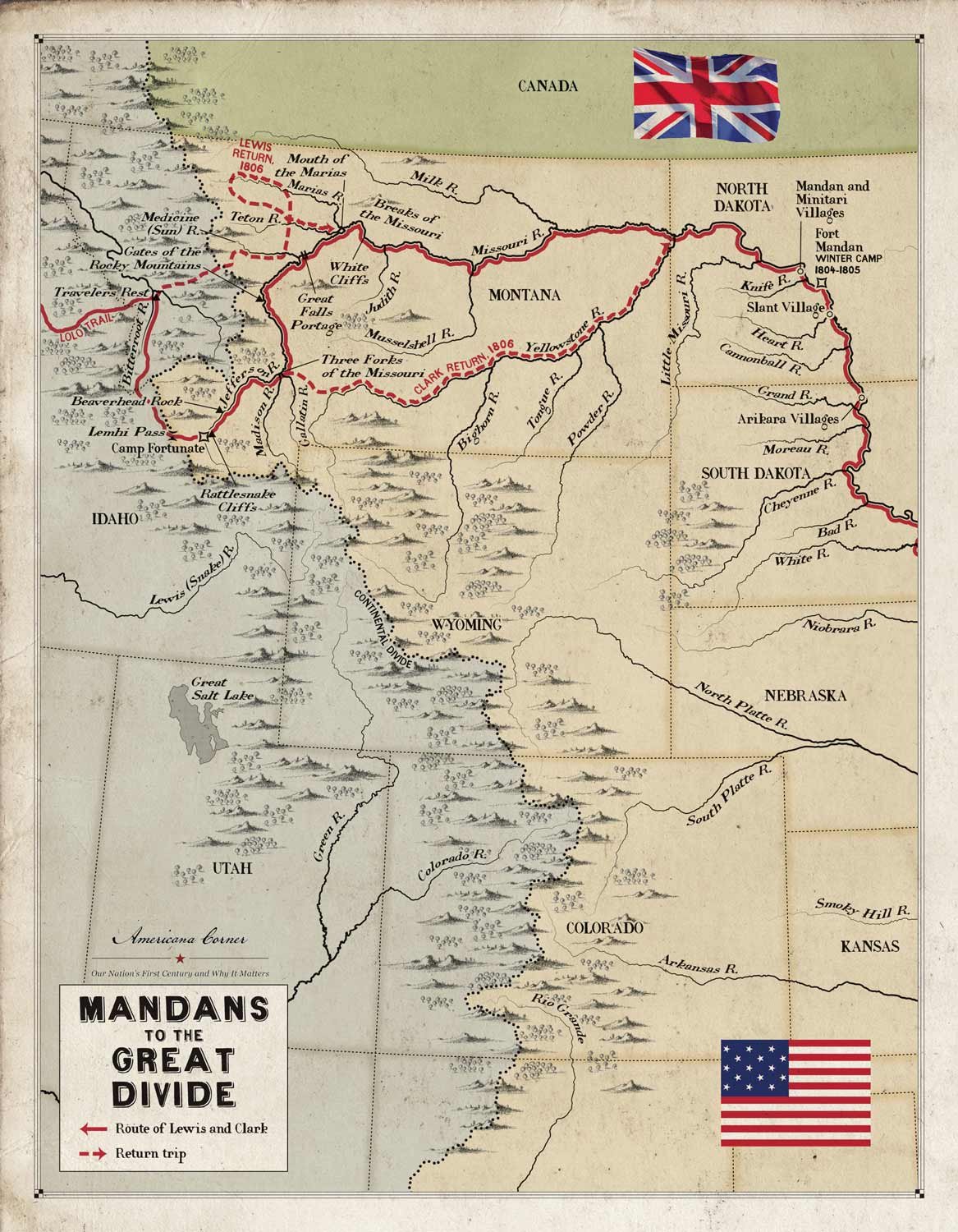

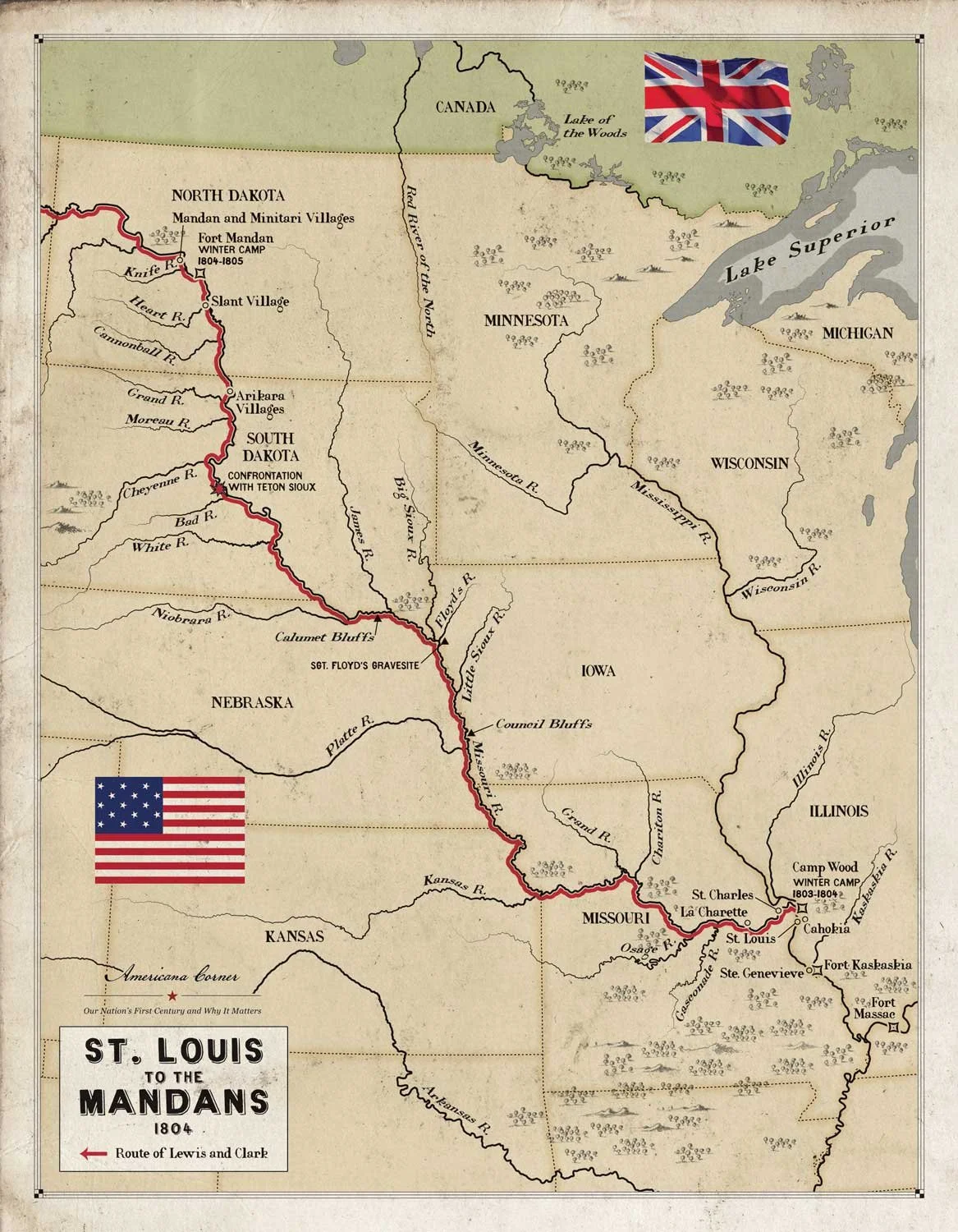

The Lewis and Clark Expedition had been traveling almost straight west and upstream since leaving the Mandan villages in early April 1805. They had safely made it to the west side of the Continental Divide, a great accomplishment, and now would be floating downstream on the western river system that would lead them to the Pacific Ocean. But to reach the navigable waters of the Columbia River, they first had to traverse the broad and formidable Rockies, the most challenging natural obstacle the Corps encountered during their three-year journey.

They left their camp near Lemhi Pass on September 1 and, led by Old Toby, their Shoshone guide, headed north, first along the North Fork of the Salmon River and then up the scenic Bitterroot River Valley. On September 5, they encountered the Flathead, or Salish, close relations to the Shoshone, from whom they purchased more horses, including three colts that the captains planned to use for food during their crossing of the Bitterroot Range. After a few days making final preparations at a camp dubbed Traveler’s Rest, the Corps headed up Lolo Creek on September 11 towards what would be the most demanding stretch of the entire expedition.

The route they followed, the Lolo Trail, was woefully inadequate for their needs; the trail was narrow and there was no game to hunt. Three days into the trek, Old Toby got lost and, in trying to regain the trail, several horses slipped and rolled down the steep hills. When the men finally made camp on September 14, they were out of food and killed one of the colts for meat. Two days later, the expedition awoke to fresh snow which continued all day, soaking the men to the bone. Clark noted in his journal, “I have been wet and as cold in every part as I ever was in my life.” There was still no game in the area and a second colt was killed that night to feed the men, and the third and final colt became supper the next day.

George Catlin. “No Horns on His Head, a Brave.” Smithsonian American Art Museum.

The horses were struggling as well and close to starvation as there had been no grass on which to feed for several days. Between fatigued men and horses, snow, and a wretched trail, the Corps was only making ten miles a day. The situation was getting desperate, but turning back was not an option. The captains sensed the men were reaching their breaking point and so, on September 18, Clark went ahead with six hunters to find meat for the expedition while Lewis brought up the rest of the Corps. That night’s dinner consisted of a thin soup made from a few dried roots, some bear oil, and twenty pounds of candles. Finally, on September 20, the men emerged from their mountain odyssey and found a wild horse Clark had killed and hung up to feed the men. As Lewis noted, the party “made a hearty meal on our horse beef much to the comfort of our hungry stomachs.” The worst was now behind them and, late in the afternoon of September 22, Lewis led the men into a small Nez Perce village. Over the course of eleven days, the Corps had traveled 160 miles over some of the most demanding terrain on the continent, one of the great forced marches in American history. The captains had exhibited superb leadership and the men tremendous perseverance and hardiness. More so than any other episode of the expedition, this trek demonstrated how Lewis and Clark had transformed these untrained men into a cohesive military unit.

Lewis and Clark spent the next two weeks at the Nez Perce village of Twisted Hair, building dugout canoes and preparing for the final push to the Pacific, and during that time developed a great respect for the Nez Perce. They were the largest and most powerful tribe in the Pacific Northwest and owned more horses than any Indian nation in North America. Much like the Shoshone and the Flatheads, the Nez Perce were helpful and hospitable to the Americans with Twisted Hair offering to watch over the expedition’s horse until the men returned in the Spring and even preceding the Corps downstream to inform his kinsmen to assist the Americans.

On October 8, the Corps pushed their canoes into the Clearwater River and began the final leg of their journey to the ocean, this time traveling downstream. The men made good time, reaching the Snake River in two days and the Columbia on October 16, where they began to see natives with European goods such as cloth blankets and jackets. Interestingly, due to a lack of game near the river and with no salmon running, the men purchased as many dogs as they could obtain and dogmeat became their main nourishment for several weeks. The Corps soon encountered the start of a fifty-five mile stretch of majestic rapids beginning at a place called the Dalles (French for rapids) and continuing to the Cascades of the Columbia, which sadly are now drowned under a series of dams. The water was terribly turbulent with Clark describing it as “agitated gut swelling water, boiling and whorling in every direction” with short runs of placid water in between. Lewis and Clark decided to portage where they must but, for the most part, run the rapids in their canoes. When the local natives learned that these white strangers planned to navigate through the narrows, something the Indians refused to do, hundreds lined the riverbank to see them drown in the Columbia. Much to their astonishment, the intrepid Americans survived the ordeal with only a few lost provisions. But they did lose Old Toby, their Shoshone guide, who cared little for the rapids and headed for home after enduring the first set.

Then, on November 7, 1805, a watershed moment for the Corps of Discovery, Clark famously noted in his journal that day, “Ocian in View! O! the joy!” and then added “Ocian 4142 Miles from the Mouth of Missouri R.” Lewis and Clark had made it to the Pacific.

Next week, we will discuss wintering at Fort Clatsop. Until then, may your motto be “Ducit Amor Patriae,” love of country leads me.

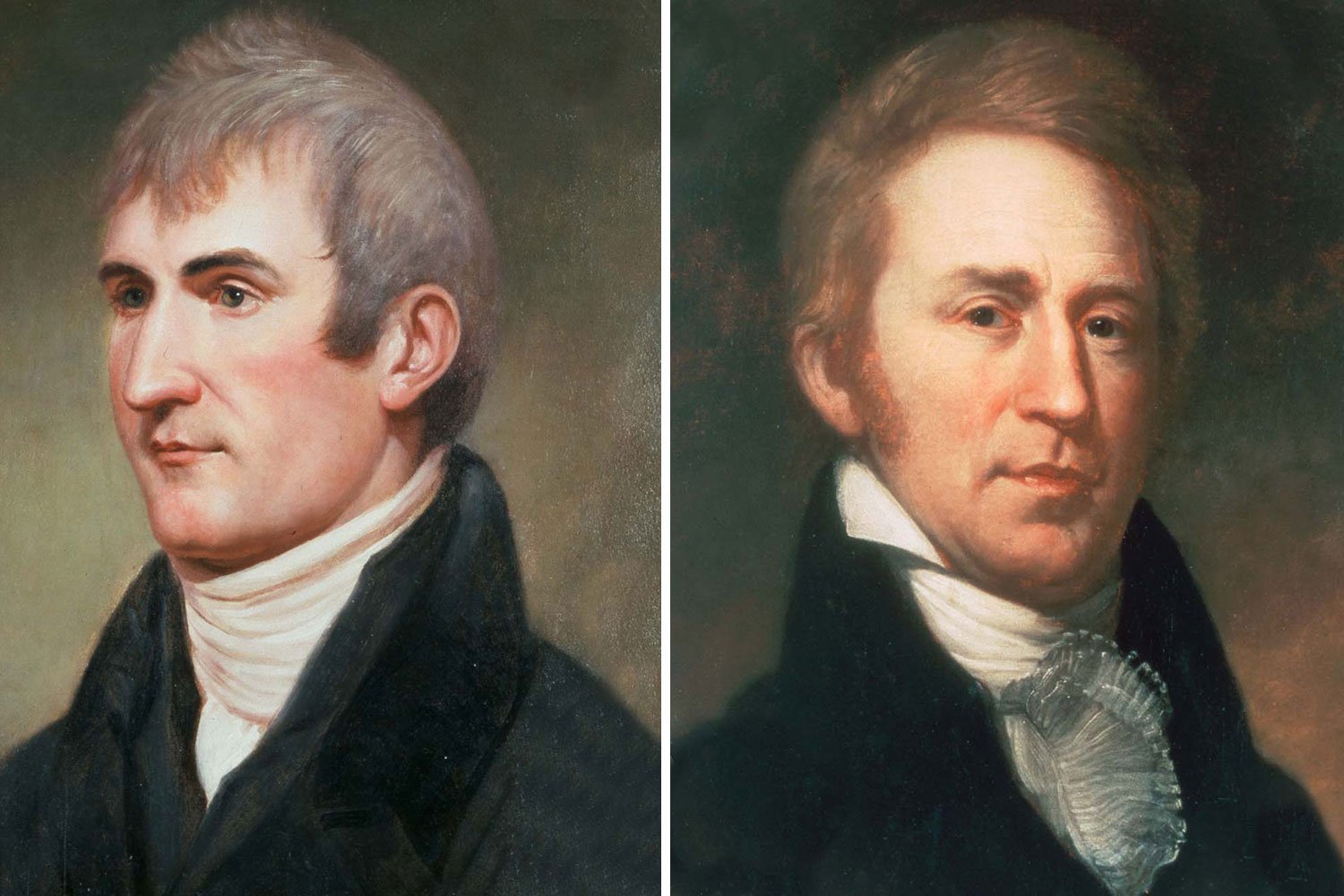

Captains Meriwether Lewis and William Clark had guided the Corps of Discovery four thousand miles to the Pacific Ocean, and they planned to continue their explorations on the return leg of their journey. The plan was to temporarily split up the Corps with Clark taking one group to descend and explore the Yellowstone to its junction with the Missouri, Sergeant Ordway leading another party to the Falls of the Missouri and there make preparations to portage the Falls, while Lewis was to lead a third group up the Marias River and determine its northern most latitude to further establish the boundaries of the Louisiana Purchase.