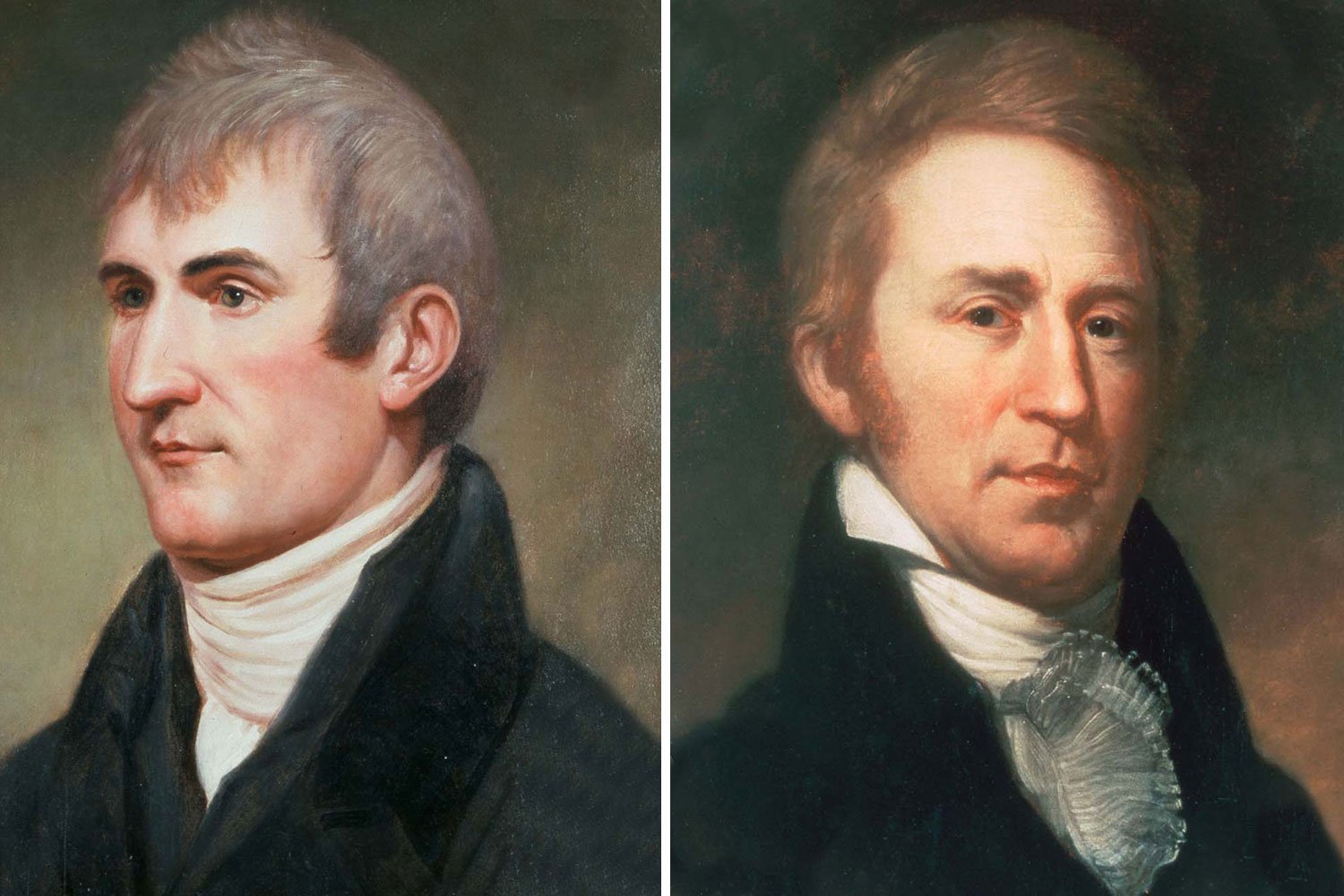

Lewis and Clark Expedition, Part 6: The Wonders of the Upper Missouri River

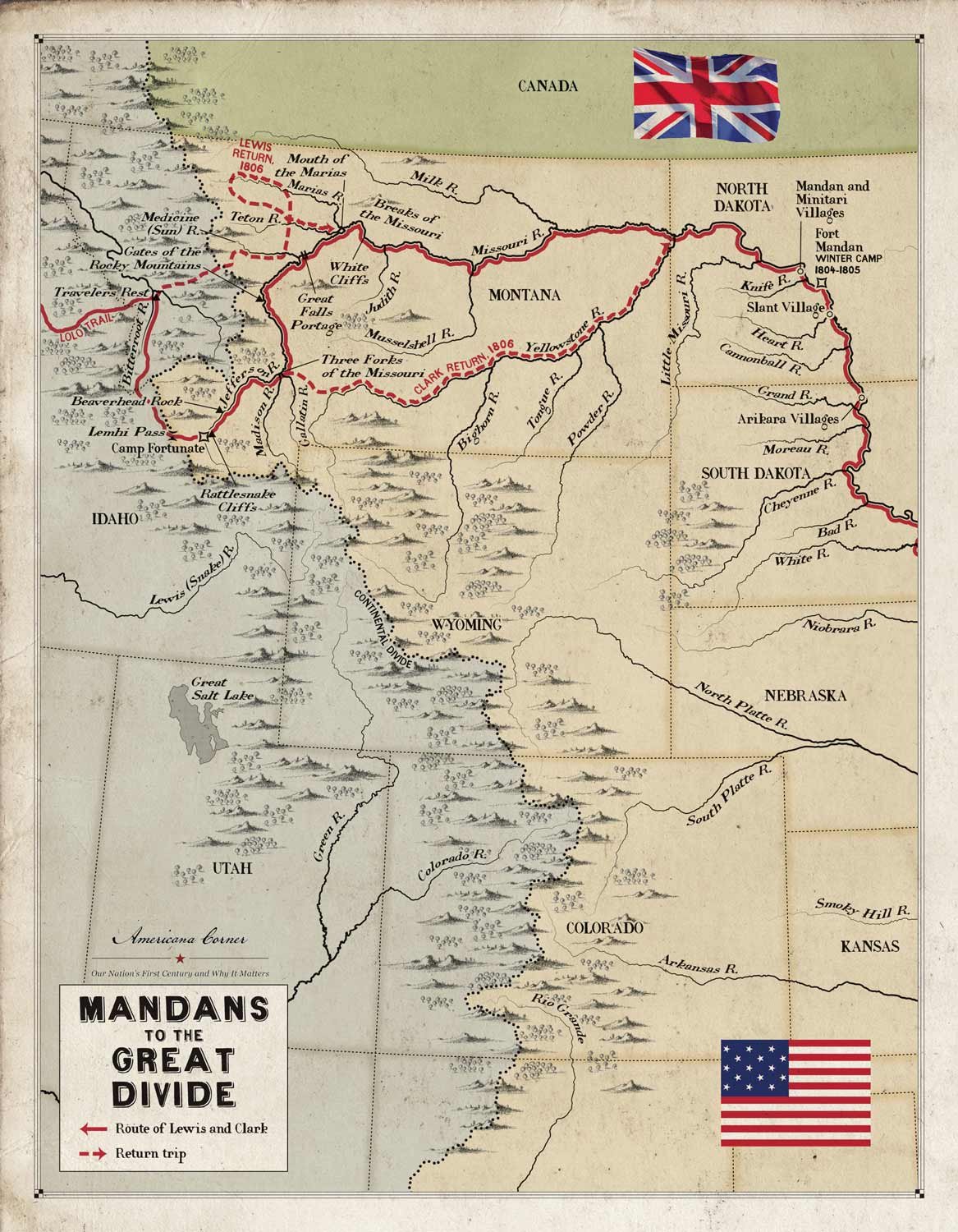

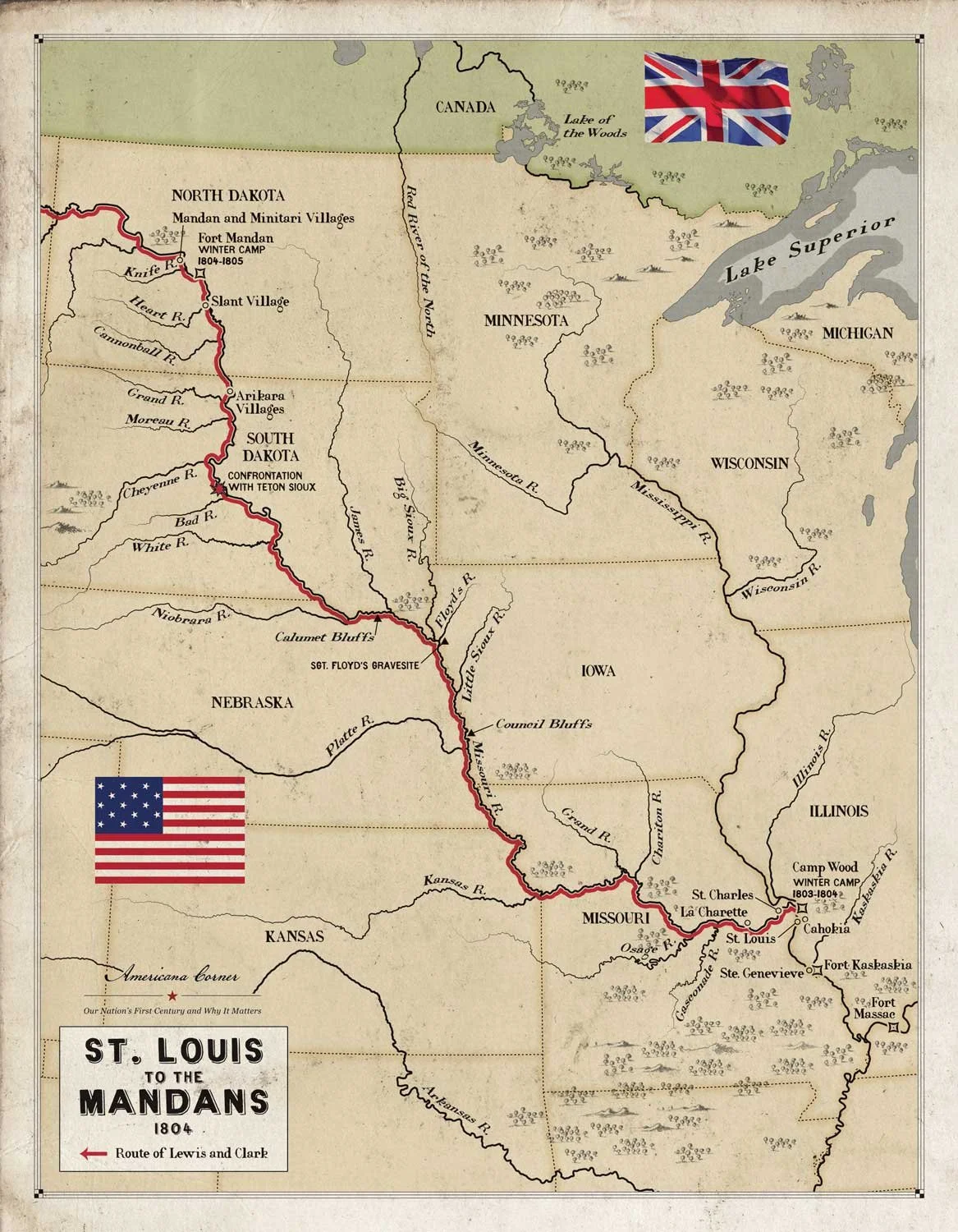

As Lewis and Clark continued their journey up the Missouri River in 1805, the Corps was moving further and further from civilization with every stroke of their paddles. Although the Corps had been made aware of the countless wonders to the west through conversations with the Mandans and Hidatsas, it was quite another thing to observe the wonders for themselves, and at seemingly every bend in the river there were new discoveries. On May 3, they came upon the Porcupine River and a week later it was the Milk River, named for the color of its water originating in today’s Glacier National Park. In early June, Lewis and Clark arrived at the mouth of yet another significant river, but one of which they had not been forewarned by the Hidatsas. Due to its size, Lewis noted “An interesting question was now to be determined; Which of these rivers was the Missouri?” It was already June, and with the vast mountains looming before them and more than a thousand miles to go, should they choose the wrong river, the expedition would be in serious jeopardy.

The captains led different parties up both streams for two days, traveling some fifty miles, and afterwards convened the men to get their opinions. Lewis noted that all the soldiers were “firm in the belief that the N. Fork (later named the Marias) was the Missouri and that which we ought to take.” But the Captains were convinced otherwise based on the color of the water from both streams and the fact that the bed of the south fork (the Missouri) was composed of smooth stones “like most rivers issuing from a mountainous country” while the bed of the north fork (Marias) was mainly muddy suggesting a course over a relatively flat plain. The captains decided to proceed up the south fork, and they chose wisely with Lewis noting the men “said very cheerfully that they were ready to follow us any wher we thought proper to direct,” a testament to the high regard in which the men held the captains.

In that broad untrammeled country, the Corps also observed countless other natural wonders. On May 26, Lewis noted in his journal that he “beheld the Rocky Mountains for the first time…covered with snow and the sun shone on it in such manner as to give me the most plain and satisfactory view.” Soon thereafter, the Corps came upon what Clark called the “Deserts of America,” a stretch of 160 miles of dry country running from today’s Fort Benton to the western end of Fort Peck Lake. Lewis described “seens of visionary inchantment” with the river coursing through “hills and river cliffs which…exhibit a most romantic appearance…The Bluffs of the river rise to the height of 300 feet and in most places nearly perpendicular.” This area comprising the Missouri River Breaks and White Rock region remains one of the most remote parts of America.

The animal kingdom they beheld was just as amazing to the Corps. On June 3, the Captains climbed a bluff and observed “the country in every derection around us was one vast plain in which innumerable herds of Buffalow were seen attended by their shepherds, the wolves and the verdure perfectly cloathed the ground;” Clark estimated one of the herds numbered in excess of ten thousand head. There was also an abundance of wolves and grizzlies and confrontations with the latter were becoming all too frequent, with Lewis noting after being chased by a wounded grizzly that he would “reather fight two Indians than one bear.”

“Lewis and Clark with Sacajawea at the Great Falls of the Missouri 1804.” Gilcrease Museum.

They also came upon a pile of over one hundred mangled buffalo carcasses lying and rotting along the riverbank beneath a 120-foot cliff; the stench was horrific. In his journal, Lewis described the cause of their demise as something called a “buffalo jump,” a very creative hunting technique used by some Plains Indians. A young fleet-footed Indian boy dressed in a buffalo skin positions himself between a small herd of buffalo and a cliff, close enough to be observed by the herd. Hunters then approach the herd from three sides and startle the buffalo to get them running towards the Indian boy who races to the cliff with the buffalo following close behind. With luck, the boy dives to the side and the buffalo go over the cliff, but this task did not lend itself to much longevity. As Lewis notes “the part of the decoy I am informed is extremely dangerous, if they are not very fleet runners the Buffalo tread them under foot and crush them to death, and sometimes drive them over the precipice also, where they perish in common with the Buffalo.”

But perhaps the most wonderous site they experienced on their entire journey was the Great Falls of the Missouri which Lewis first observed on June 13, calling them “the grandest site I ever beheld.” The Falls, located just east of today’s Great Falls, Montana, are a series of waterfalls over the course of twelve river miles with a combined drop of 187 feet in vertical plunges and another 425 feet of riverbed descent. To have witnessed these falls in the rawness of their untouched natural beauty was almost too much for Lewis who struggled to adequately describe it for posterity in his journals. However, the geographic elements that created the site’s grandeur also created the most formidable challenge for the Corps since leaving the Mandan villages. On June 22, unable to navigate the falls, the expedition commenced a seventeen-mile-long portage, transporting four canoes, two pirogues, and all their possessions over a terrain chock full of deep ravines. The portage of the Great Falls proved very difficult, and the expedition lost a month of precious time. Finally, on July 15, they were off again.

It had been over three months since the Corps left the Mandan villages and they had seen no Indians, some of the men counting that as a blessing. However, Lewis and Clark knew they must soon find the Shoshone from whom they could purchase horses or there would be little chance of crossing the Rockies.

Next week, we will discuss the Corps crossing the Great Divide. Until then, may your motto be “Ducit Amor Patriae,” love of country leads me.

Captains Meriwether Lewis and William Clark had guided the Corps of Discovery four thousand miles to the Pacific Ocean, and they planned to continue their explorations on the return leg of their journey. The plan was to temporarily split up the Corps with Clark taking one group to descend and explore the Yellowstone to its junction with the Missouri, Sergeant Ordway leading another party to the Falls of the Missouri and there make preparations to portage the Falls, while Lewis was to lead a third group up the Marias River and determine its northern most latitude to further establish the boundaries of the Louisiana Purchase.