Lewis and Clark Expedition, Part 2: Thomas Jefferson’s Western Vision

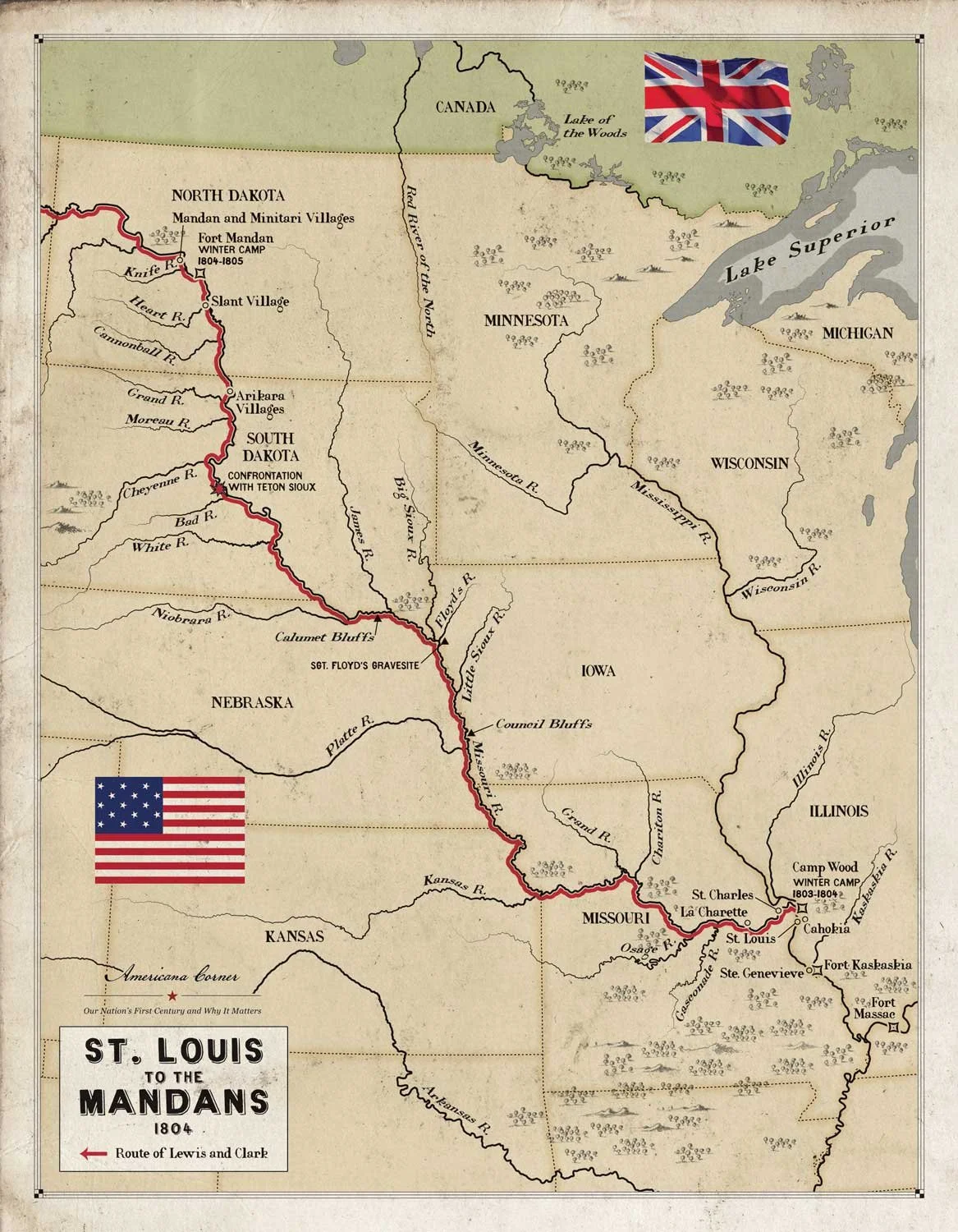

By the time they began to assemble the Corps of Discovery in the summer of 1803, Thomas Jefferson and Meriwether Lewis knew more than anyone else about the Louisiana Territory, that immense wilderness the country had recently purchased from France. Although Jefferson had never ventured more than fifty miles west from Monticello, he had dreamed of the trans-Mississippi and studied the region extensively over the previous two decades, even trying unsuccessfully to send exploratory expeditions on several occasions.

While both Jefferson and Lewis had a good understanding of what it would take to reach the Western Ocean, only Jefferson fully understood what was needed for the expedition to be judged as a success in his visionary eyes. Accordingly, on June 20, 1803, President Jefferson drafted his official instructions to Lewis for the great journey to come, “The object of your mission is to explore the Missouri river and such principal stream of it, as, by its course and communication the waters with the Pacific Ocean, whether the Columbia, Oregan, Colorado or any other river may offer the most direct and practicable water communication across this continent for the purposes of commerce.”

Jefferson goes on at length describing all the things he wanted to learn from the expedition, observations of latitude and longitude “at all remarkable points on the (Missouri) river” and “interesting points of the portage between the Missouri and the water offering the best communication with the Pacific Ocean.” With future commerce in mind, Jefferson tasks Lewis to “make himself acquainted with the names of the (Indian) nations” as well as their numbers, traditions, habits, and religious beliefs so they can more quickly become good trading partners for the United States, especially regarding the fur trade along the Pacific coast. The President further instructs Lewis to record his observations of the vegetation and animals he encounters, especially those previously unknown to science. Ever the farmer and with an eye towards future agricultural endeavors, Jefferson also asked Lewis to note soil and climatic conditions in each region.

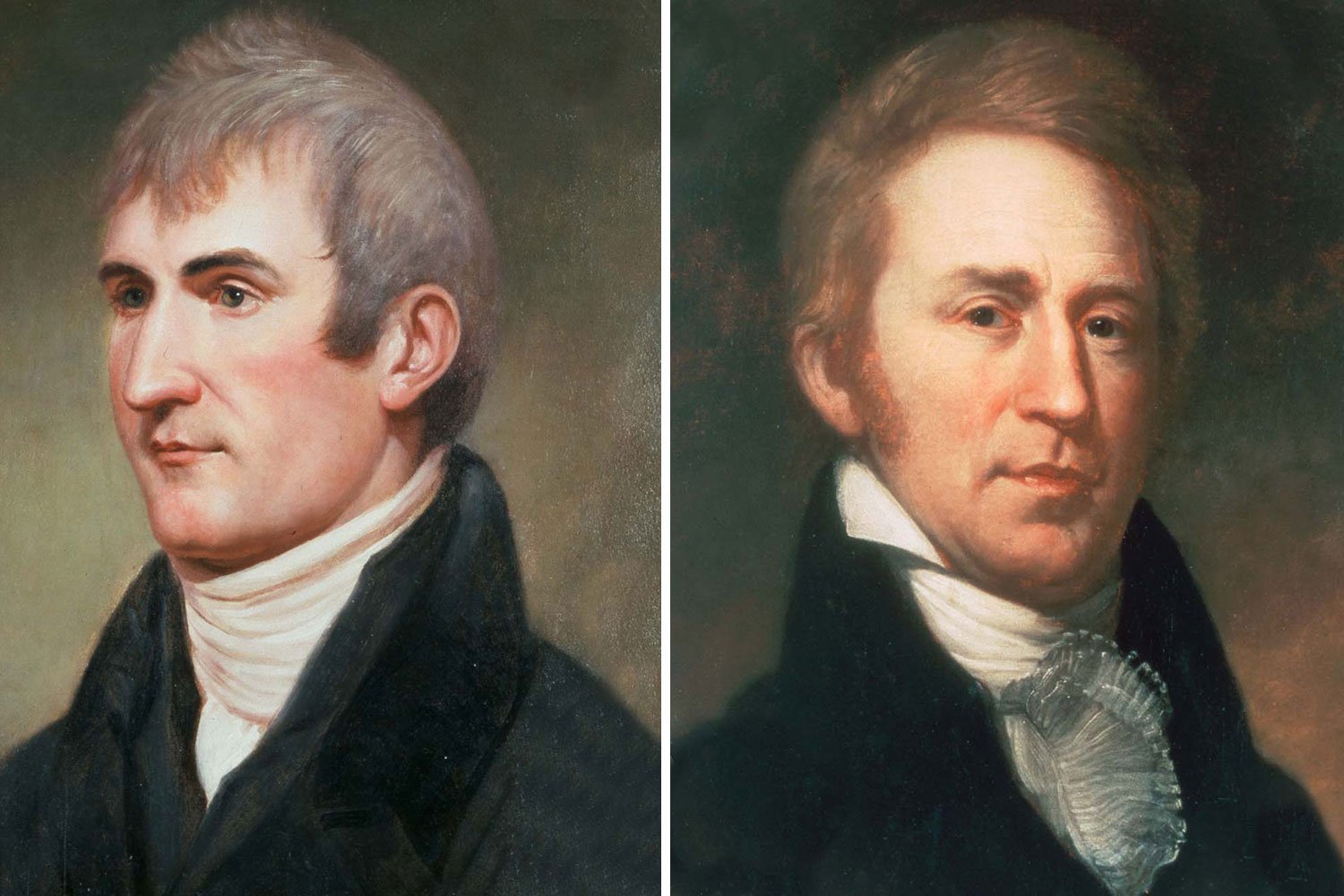

To accomplish this mission, Jefferson and Lewis initially envisioned a twelve-man contingent of soldiers to accompany Lewis. This number would eventually double and include a second officer, William Clark. Once assembled, the Corps of Discovery would operate very much like a military unit with all the martial aspects of a small frontier garrison, albeit with some minor modifications when they were on the move. The men ate meals at prescribed times and the basic menu consisted of a three-day rotation, day one was hominy and lard, day two salt pork and flour, and day three cornmeal and pork. To augment this sparse diet and to stretch their provisions, a few men hunted each day for fresh meat which provided a welcome relief. When game was plentiful, the men ate upwards of nine pounds of meat a day. The men also received their daily ration of one gill of whiskey (roughly five ounces) at the end of their day but only while it lasted (they started the journey with 120 gallons and ran out in the summer of 1805). Although neither of the captains were harsh men, discipline was rigidly maintained as Captain Clark turned these new recruits into soldiers and, early on in the training, several of the men received lashes across the back for unacceptable military conduct.

Edgar Samuel Paxson. “Lewis and Clark at Three Forks.” Montana Historical Society, Wikimedia.

Most of the permanent party were soldiers, including five who would return to St. Louis the following spring with dispatches and specimens for President Jefferson. The Corps was divided into three squads, each with a Sergeant and there were two officers, Lewis and Clark. Although generally referred to as “the two Captains,” that was not exactly true. For some unexplained reason, Secretary of War Henry Dearborn put Clark’s commission through as a Lieutenant despite Jefferson’s assurances that Clark would be a Captain. Such was Lewis’s respect for Clark that he only shared the disappointing news with Clark and otherwise kept it secret and none of the soldiers ever knew. There were also four civilians who stayed with the Corps from the Mandan villages to the Pacific Ocean and back, including one woman, the Shoshone Sacagawea who gave birth to a son in winter camp and took him on the march west, and one slave, Clark’s man York, and rounding out the party was Lewis’s faithful Newfoundland dog, Seaman, who made the entire trip.

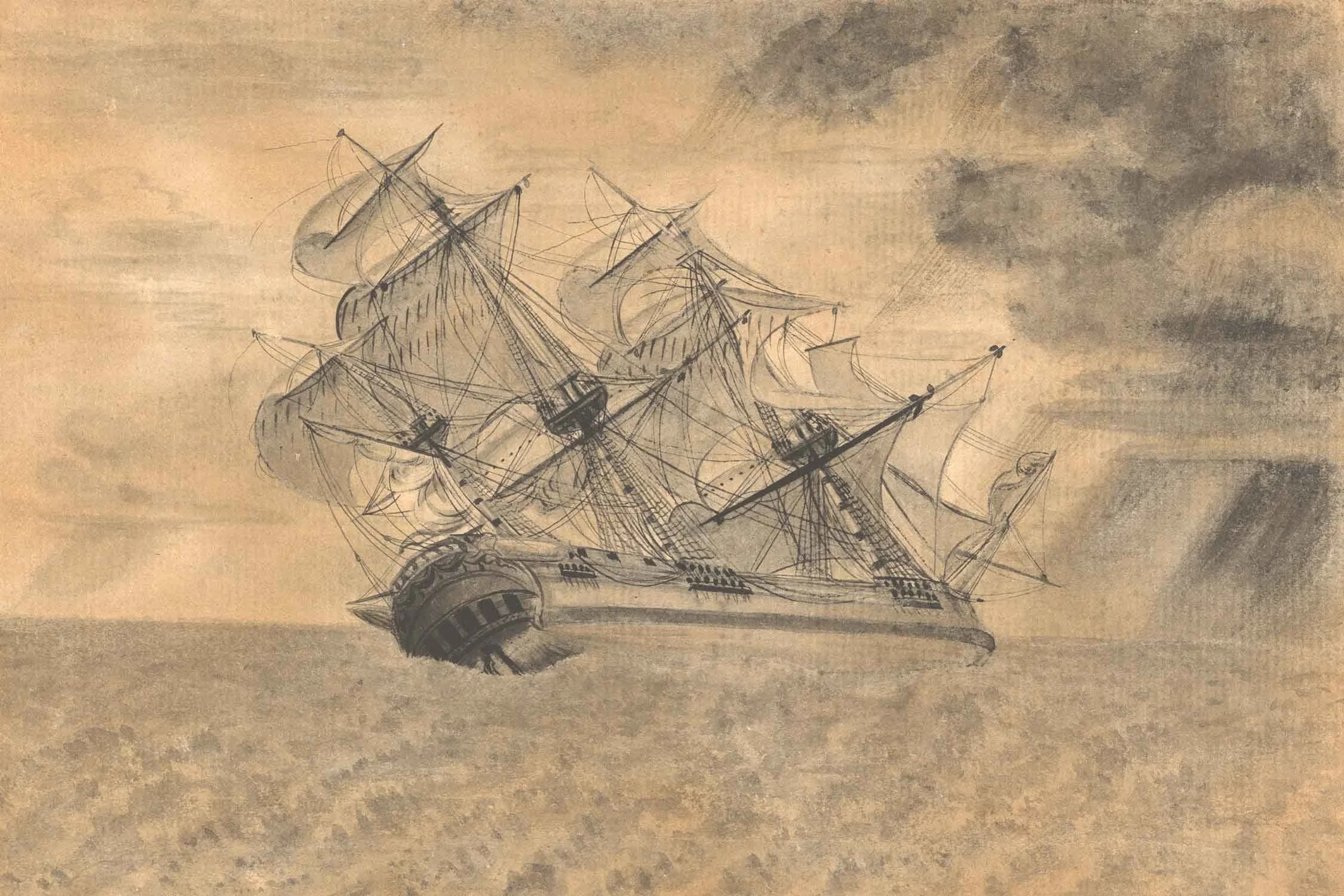

Without question, the most important piece of equipment for the expedition was the keelboat that would carry the Corps on their journey up the Missouri to the Mandan villages. The boat, designed by Lewis and built in Pittsburgh, was fifty-five feet long and twelve feet wide at midships with a thirty-two-foot-high mast for a square sail when the wind was favorable and eleven benches for rowing when it was not. In those all-too-frequent instances when the water was not deep enough for rowing or the sandbars too plentiful or the wind unfavorable, the men shoved long steel tipped poles into the muddy river bottom and pushed the boat upstream. The work was backbreaking and there were days when the Corps advanced less than ten miles. Generally, Lewis spent his day walking the riverbank looking for interesting flora and fauna and making observations while Clark, the better boatman and troop commander, remained in charge of the keelboat and the men.

In the end, this versatile craft functioned as an ark for the men and a floating general store with provisions and every conceivable tool or instrument the Corps would need. Perhaps most importantly and indicative of the potentially hostile territory into which the Corps was ascending, the keelboat was very much a warship with its bow mounted small cannon and four blunderbusses, or heavy shotguns, mounted on swivels and capable of firing twelve musket balls at a time. Additionally, with Jefferson’s approval, Lewis had ordered a large arsenal of Pennsylvania rifles, knives, tomahawks, gunpowder, and lead from the United States arsenal at Harpers Ferry.

In the end, the Corps of Discovery went forward remarkably well prepared for what they would encounter over the next few years, a testament to the thorough planning of President Jefferson.

Next week, we will discuss Lewis and Clark, the leaders of the Corps. Until then, may your motto be “Ducit Amor Patriae,” love of country leads me.

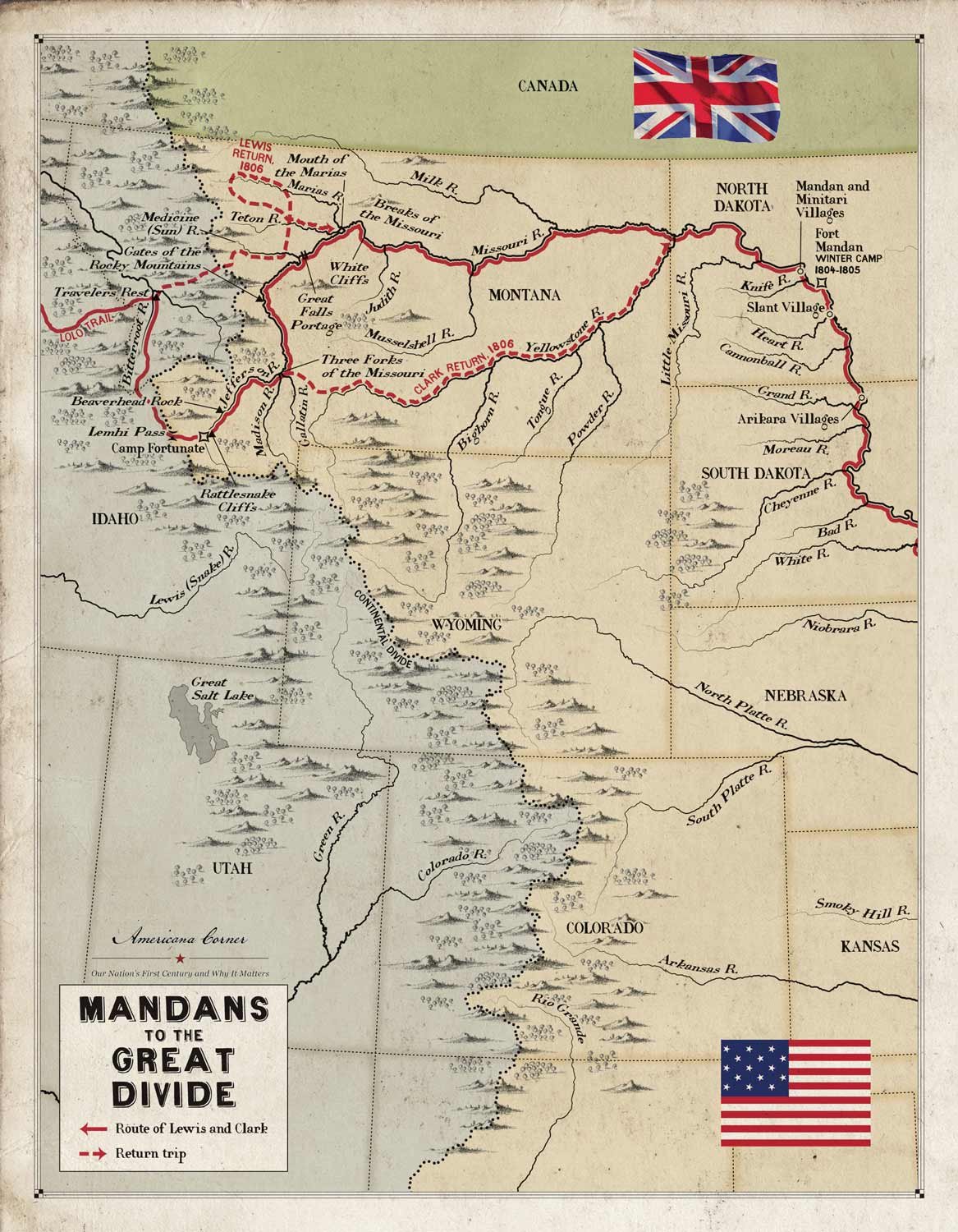

Captains Meriwether Lewis and William Clark had guided the Corps of Discovery four thousand miles to the Pacific Ocean, and they planned to continue their explorations on the return leg of their journey. The plan was to temporarily split up the Corps with Clark taking one group to descend and explore the Yellowstone to its junction with the Missouri, Sergeant Ordway leading another party to the Falls of the Missouri and there make preparations to portage the Falls, while Lewis was to lead a third group up the Marias River and determine its northern most latitude to further establish the boundaries of the Louisiana Purchase.