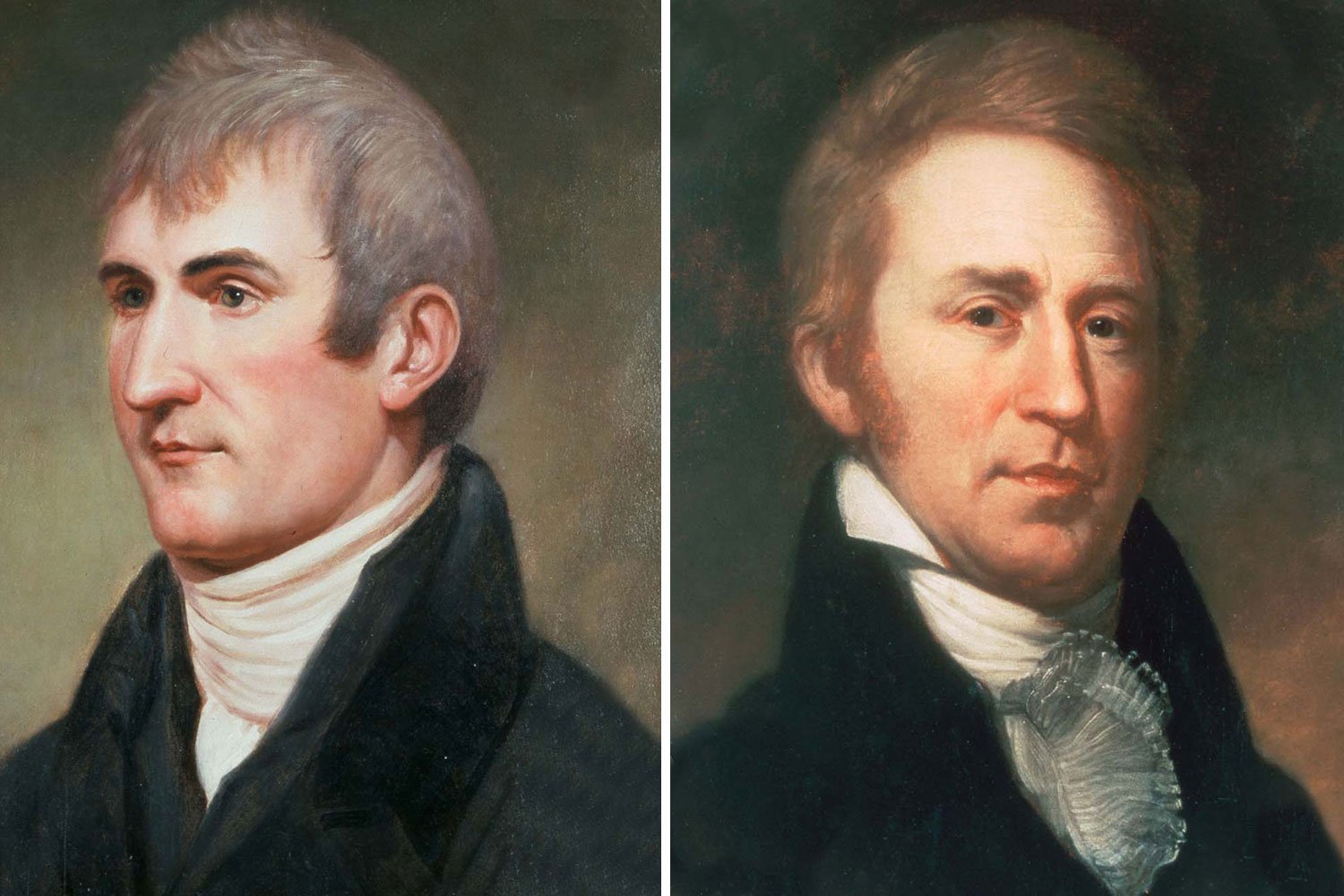

Lewis and Clark Expedition, Part 3: Leaders of the Corps of Discovery

In 1801, Meriwether Lewis was a Captain serving as the paymaster for the First Infantry Regiment of the United States Army. In March, he received a letter from Thomas Jefferson, the newly inaugurated President, asking Lewis to become his private secretary. Lewis, whose family was friends with the Jefferson clan, accepted at once, and thus began a close working relationship, one in which Jefferson became a father figure to Lewis and mentored his young subordinate on policy matters, including his dreams of western exploration and expansion.

At the time, Lewis was twenty-seven years old, having been born on August 18, 1774, on Locust Hill Plantation in Albemarle County, Virginia to William and Lucy Lewis. His father had been an officer in the Continental Army but died in 1779, and his mother soon remarried and moved to Georgia. At age thirteen, Meriwether moved back to Virginia to begin his schooling with local tutors which lasted for five years until his stepfather died in 1791. Lewis then brought his mother and younger siblings back to live with him at Locust Hill, and at age eighteen became a planter, managing his own estate. But, in 1794, when President Washington called for volunteers to suppress the Whiskey Rebellion, Lewis bade goodbye to plantation life and joined the Virginia militia, taking a path that eventually led him to President Jefferson’s side and the adventure of a lifetime.

As Jefferson’s plans for exploring the lands west of Mississippi took on greater urgency, he turned to Lewis, a man he had come know as well as any man, to lead an American expedition to the mouth of the Columbia and, importantly, to get there ahead of the British. As Jefferson later explained, Lewis possessed “the firmness of constitution and character, prudence, habits adapted to the woods, and a familiarity with Indian manners and character requisite for this undertaking.” For the next year, the two men studied Jefferson’s collection of books and maps on the lands west of the Mississippi. By March 1803, Jefferson felt Lewis was ready for more detailed scientific studies critical to the mission’s success and sent him to Philadelphia to be tutored by several of Jefferson’s fellow members of the American Philosophical Society. From Andrew Ellicott, Lewis learned astronomy and Dr. Benjamin Rush advised him on medical matters, while Dr. Benjamin Barton taught Lewis botany and Dr. Caspar Wistar instructed him on anatomy. Completing his studies in mid-June, Lewis returned to Washington, soon after word of the Louisiana Purchase had been received, with plenty of details to work out with the President. Importantly, both Jefferson and Lewis recognized the need to assign a second officer to the expedition in the event something unfortunate were to happen to Captain Lewis, and the man Lewis wanted to fill this coveted position was William Clark.

“President Thomas Jefferson and Meriwether Lewis.” National Park Service

A fellow Virginian, Clark was the youngest brother of George Rogers Clark, one of the greatest heroes of the American Revolution. Clark, who was four years older than Lewis, was born August 1, 1770, in Caroline County, Virginia. He joined the Kentucky militia at the age of nineteen and, in 1792, was commissioned a lieutenant in the Legion of the United States, serving under General Anthony Wayne. Clark was promoted to Captain and given command of the Chosen Rifle Company, a unit of elite marksmen, and, on August 20, 1794, led them in the decisive Battle of Fallen Timbers that crushed the Confederacy under the Shawnee chief Blue Jacket and ended the Northwest Indian War. In November 1795, Lieutenant Meriwether Lewis was assigned to Clark’s company and served under him until Clark retired from the military for health reasons in the summer of 1796. But in those short six months, the two men established a mutual respect and unbreakable bond that neither forgot.

When the opportunity was presented to have a fellow officer at his side to share the burden of command, Lewis immediately chose Clark and sent him a letter dated June 19, 1803, in which Lewis discussed the coming expedition in detail and all Lewis had done in preparation for it. Then, as Clark read on, he received the shock of his life. “Thus my friend you have a summary view of the plan, the means and the objects of this expedition. If therefore there is anything under those circumstances, in this enterprise, which would induce you to participate with me in it’s fatiegues, it’s dangers and it’s honors, believe me there is no man on earth with whom I should feel equal pleasure in sharing them as with yourself.”

Clark must have pinched himself to make sure he was not dreaming as he read Lewis’s words. Clark was a man built for hardy adventures and had commanded men in battle but was now living a somewhat mundane life in the tiny hamlet of Clarksville, Indiana Territory. To trade his current tedium for a marvelous tour to the Western Ocean in a joint command with his friend, must have seemed a gift from heaven. Clark immediately responded, “I will chearfully join you in an ‘official Charrector’ as mentioned in your letter and partake of the dangers, difficulties, and fatigues, and I anticipate the honors and rewards of the result of such an enterprise.”

The two men seemed tailor made to co-command the expedition; they were both about six feet tall, wiry strong, and experienced woodsmen with an extensive background of dealing with Indians. Clark had been a company commander and had a gift for leading enlisted men, a critical aspect as most of the permanent members of the expedition would be soldiers. Clark, who was also the better boatman and surveyor, would essentially shoulder most of the burden of command for the entire journey. Lewis was much more the scientist and would be the main recorder of the almost unimaginable number of flowers, animals, and natives they would encounter. Most importantly, the respect they held for each other was sincere and went to the core. Together, this dauntless duo would overcome every obstacle, every hardship, and find a solution to every problem on the most incredible journey in American history.

Next week, we will discuss the Corps of Discovery starting out. Until then, may your motto be “Ducit Amor Patriae,” love of country leads me.

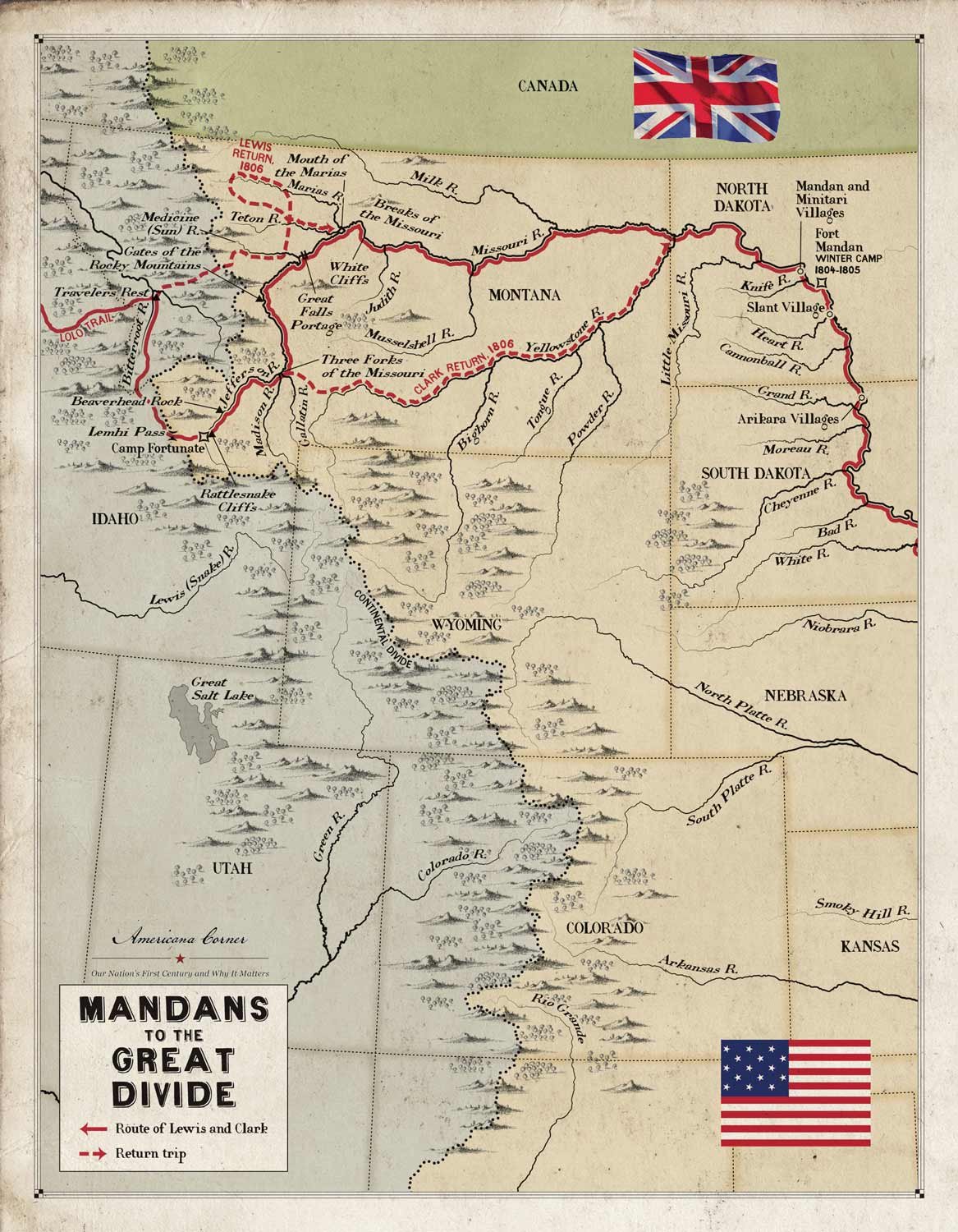

Captains Meriwether Lewis and William Clark had guided the Corps of Discovery four thousand miles to the Pacific Ocean, and they planned to continue their explorations on the return leg of their journey. The plan was to temporarily split up the Corps with Clark taking one group to descend and explore the Yellowstone to its junction with the Missouri, Sergeant Ordway leading another party to the Falls of the Missouri and there make preparations to portage the Falls, while Lewis was to lead a third group up the Marias River and determine its northern most latitude to further establish the boundaries of the Louisiana Purchase.