Lewis and Clark Expedition, Part 5: The Corps of Discovery Winters with the Mandans

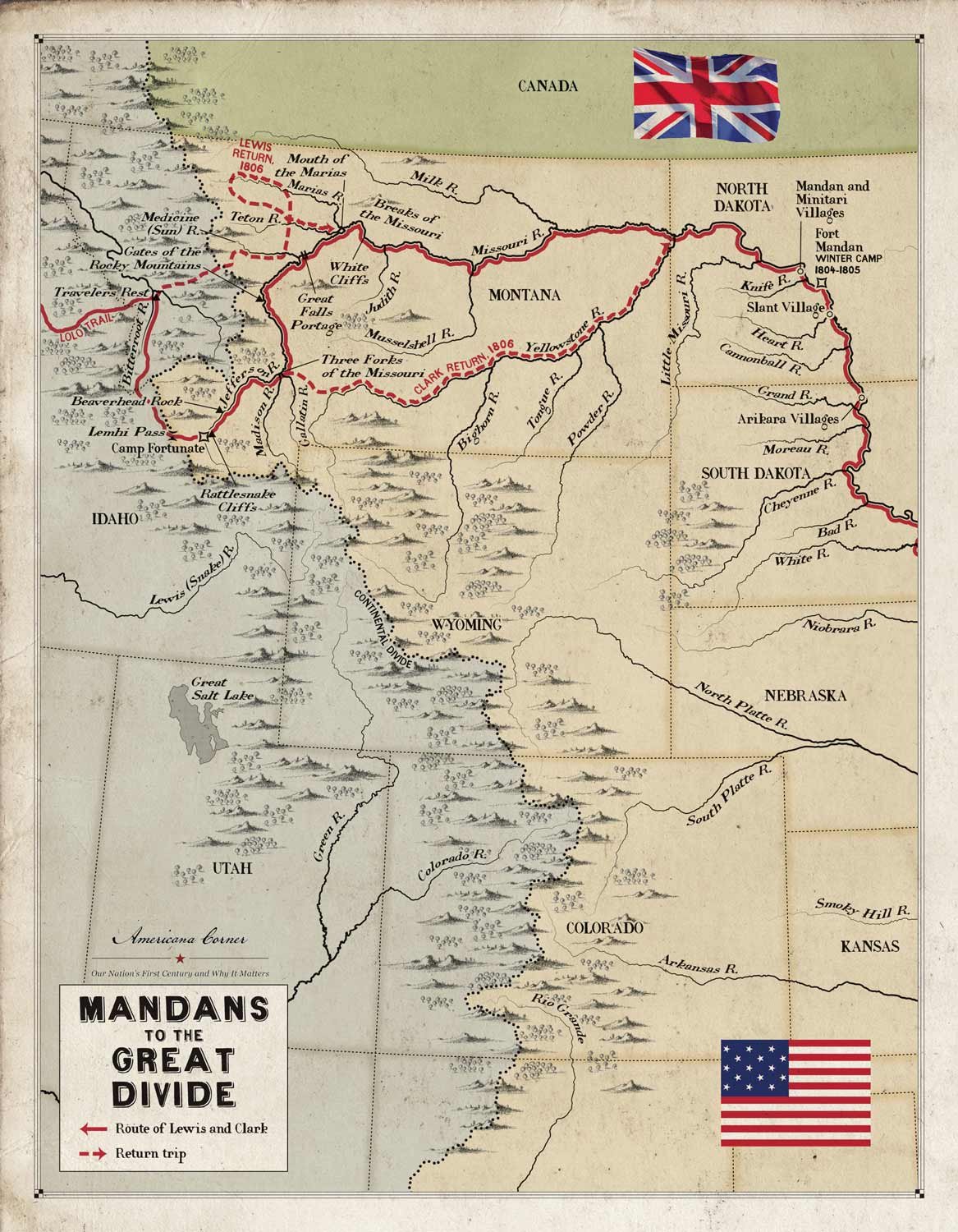

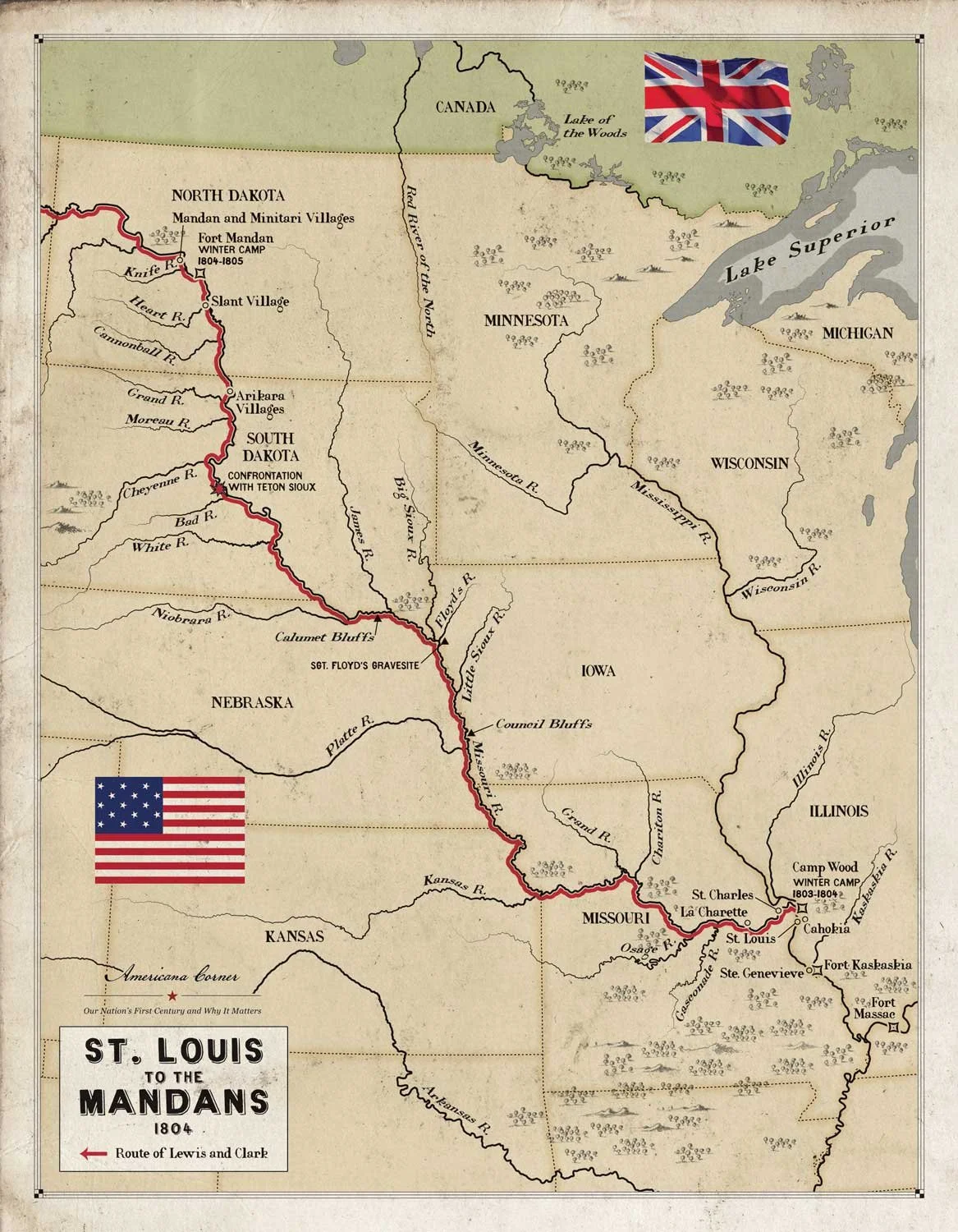

The Corps of Discovery arrived at the Mandan villages near present day Bismarck, North Dakota, in late October 1804, and prepared to settle in for the long winter. For the past five months, the Lewis and Clark Expedition had spent most days rowing or pushing their keelboat against the Missouri River’s powerful current, and the men were ready for a break. They were now 1,300 river miles upstream from the nearest civilized settlement and, although they did not know it, they had over 2,000 miles to go to reach the Pacific Ocean.

In November, the men began work on Fort Mandan on the north bank of the Missouri River, just across from the lower Mandan village. The fort’s outer palisaded walls were 18 feet high with a gate facing the river and a swivel gun mounted to command the main approach to the fort. It was a terribly cold winter with temperatures dipping to -40 degrees in January, but the soldiers were made to embrace the harsh elements rather than hide from them. Each day, the men rose early to the sounds of reveille and spent long days chopping wood for their immediate needs and hunting and curing meat and repairing equipment for the coming trip to the west. The demanding workload paid dividends as there were no disciplinary issues that winter; in fact, unit cohesion became so strong that there was not another breach of proper military conduct for the remainder of the trip. Not knowing if they would survive the expedition, the captains used their time to prepare for President Thomas Jefferson a detailed manuscript of their journey thus far called the Mandan Miscellany which they sent back in the spring.

“Portrait of Sacagawea.” World History Encyclopedia.

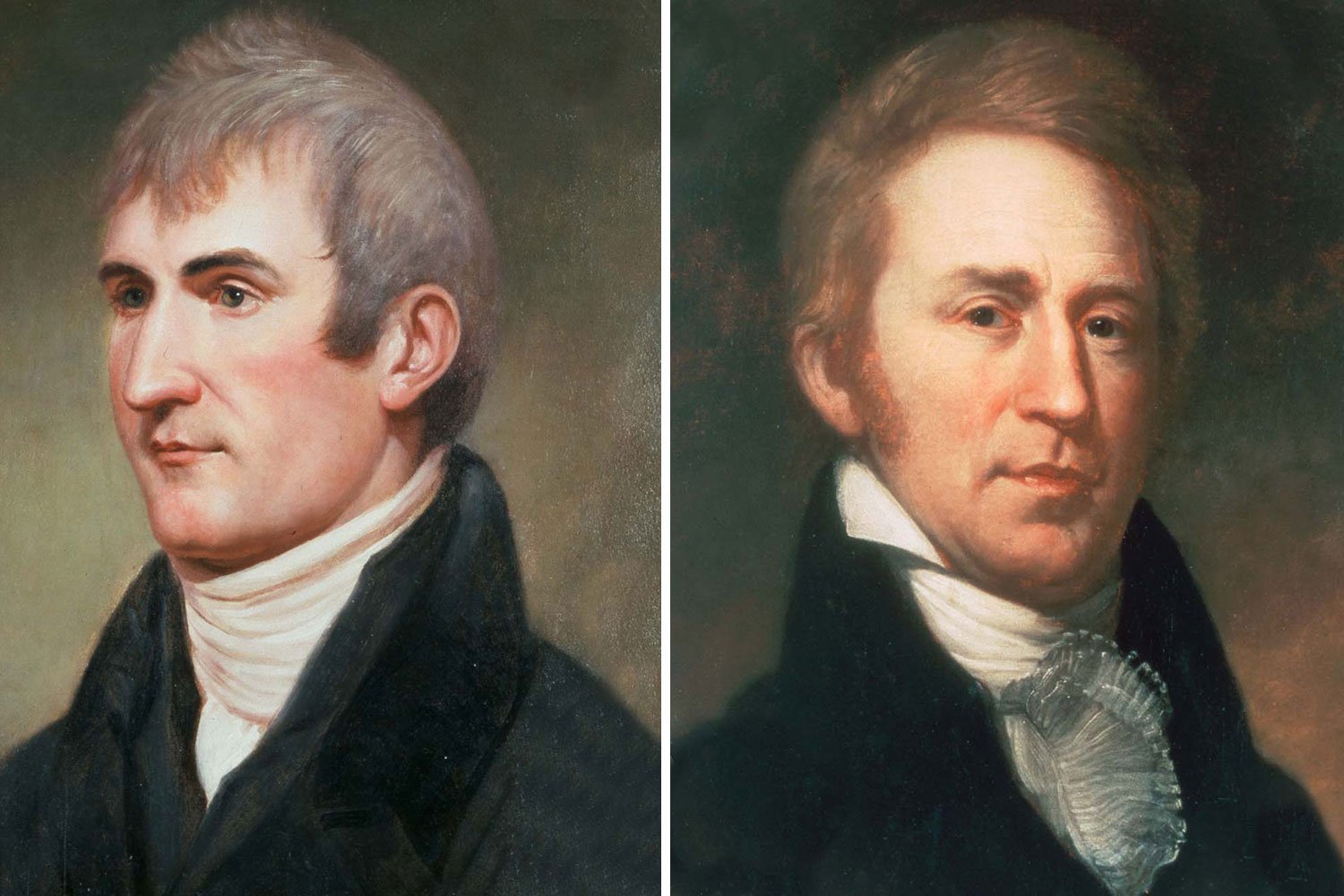

While at Fort Mandan, the captains met a French fur trader named Toussaint Charbonneau who as Clark noted, “wished to hire and informed us his 2 Squars were Snake Indians.” The Snake, or Shoshone, lived in the Rockies near the head waters of the Missouri River, and it was rumored they possessed numerous horses that the Corps would need to complete the portage between the Missouri and the Columbia. Charbonneau told Clark that his two teenage wives had been captured by a Hidatsa raiding party four years earlier and Charbonneau had won them in a bet. Although Charbonneau was a difficult man, the captains knew they would need interpreters as they moved west and so hired Charbonneau and his fifteen-year-old wife, Sacagawea, who was six months pregnant; she would give birth to a healthy boy on February 11 who she named Jean Baptiste. Lewis assisted in the delivery and noted “this was the first child which this woman had boarn and as is common in such cases her labor was tedious and the pain violent.” It was suggested to give Sacagawea a bit of the rattle of a rattlesnake to aid the delivery and Lewis complied. It seemed to work with Lewis recording, “Whether this medicine was truly the cause or not I shall not undertake to determine but she had not taken it more than ten minutes before she brought forth.” This extraordinary woman would carry Jean Baptiste for the entire journey.

On April 7, 1805, Lewis sent the keelboat down river under the command of Corporal Richard Warfington and a contingent of four privates, along with several French trappers who had helped guide the Corps north the previous year. Besides the extensive reports written by the captains, the boat was loaded with a treasure trove for President Jefferson and the American Philosophical Society; 108 botanical and 68 mineral specimens, including a root called the “white wood of the prairie” that was an antidote for rattlesnake bites, skeletons of pronghorns, and live magpies and prairie dogs. Perhaps most important was Clark’s detailed map of the lands west of the Mississippi including most tributaries of the Missouri, incredibly accurate and based on countless conversations with Indians about the region.

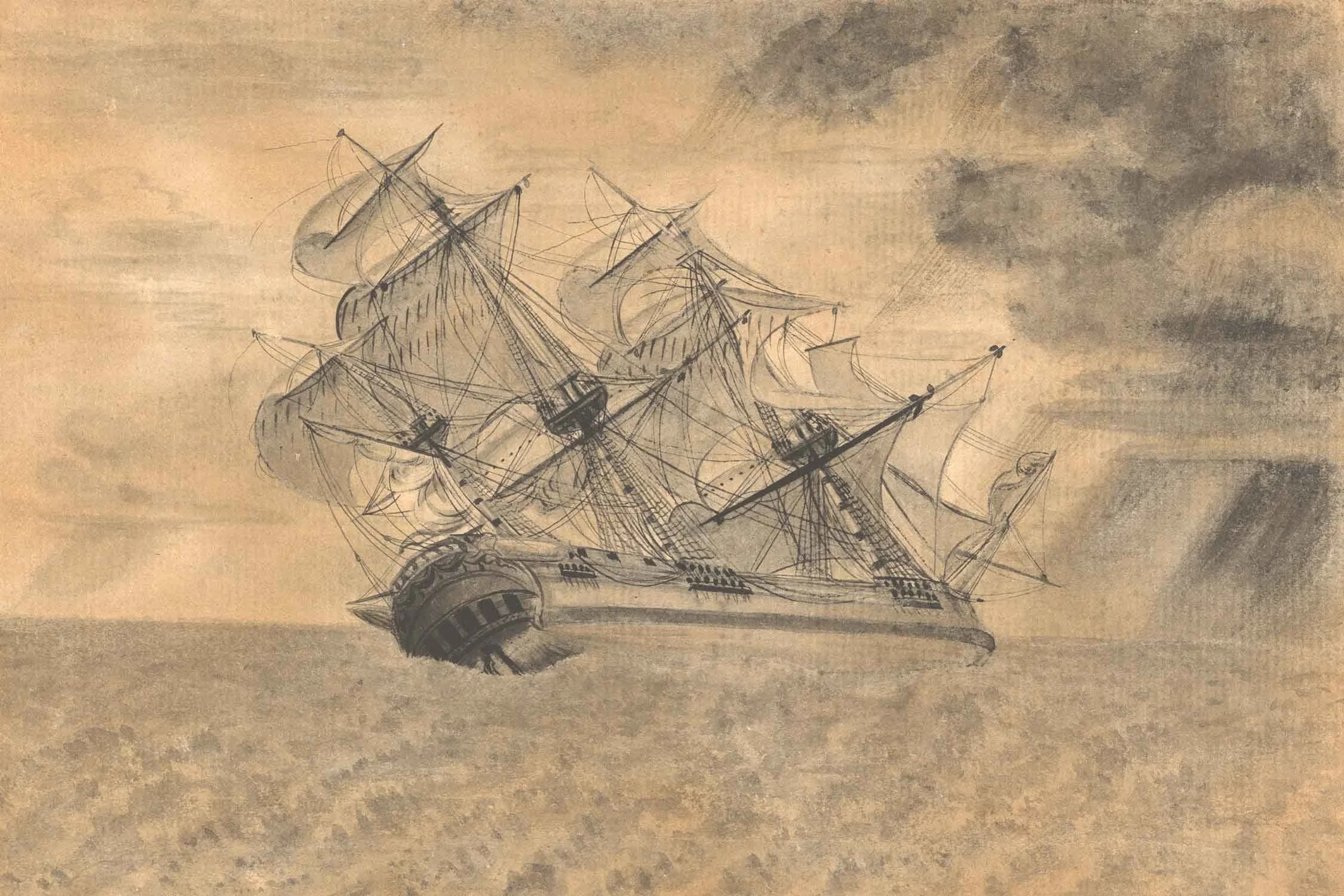

At 4pm the same day, as the permanent party of thirty-three people, including three sergeants and twenty-three privates, waved goodbye to their companions on the keelboat, the men eased their six canoes and two pirogues into the water and, after a delay of five months, continued their journey to the Pacific. Lewis’s entry in his journal that day is remarkable in that it paints a blended picture of excitement and anxiety, seemingly fully cognizant of the historical magnitude of their venture, “Our vessels consisted of six small canoes, and two large perogues. This little fleet altho’ not quite so rispectable as those of Columbus or Capt. Cook, were still viewed by us with as much pleasure as those deservedly famed adventurers ever beheld theirs; and I dare say with quite as much anxiety for their safety and preservation. We were now about to penetrate a country at least two thousand miles in width, on which the foot of civilized man had never trodden; the good or evil it had in store for us was for experiment yet to determine, and these little vessells contained every article by which we were to expect to subsist or defend ourselves. Entertaining as I do, the most confident hope of succeeding in a voyage which had formed a darling project of mine for the last ten years, I could but esteem this moment of my departure as among the most happy of my life.”

The men were now in the midst of the incredible grasslands that once constituted the Great Plains, tall verdant grass as far as the eye could see with a vast multitude of animals. On April 22, Lewis wrote, “I ascended to the top of the cutt bluff this morning, from whence I had a most delightfull view of the country…exposing to the first glance of the spectator immence herds of Buffaloe, Elk, deer, and Antelopes feeding in one common and boundless pasture.” The Corps arrived at the mouth of Yellowstone River on April 25, averaging about 20 river miles a day in their canoes and, after a few days exploring its beautiful valley, the expedition continued west.

Next week, we will discuss the wonders of the upper Missouri. Until then, may your motto be “Ducit Amor Patriae,” love of country leads me.

Captains Meriwether Lewis and William Clark had guided the Corps of Discovery four thousand miles to the Pacific Ocean, and they planned to continue their explorations on the return leg of their journey. The plan was to temporarily split up the Corps with Clark taking one group to descend and explore the Yellowstone to its junction with the Missouri, Sergeant Ordway leading another party to the Falls of the Missouri and there make preparations to portage the Falls, while Lewis was to lead a third group up the Marias River and determine its northern most latitude to further establish the boundaries of the Louisiana Purchase.