The Battle of Blue Licks

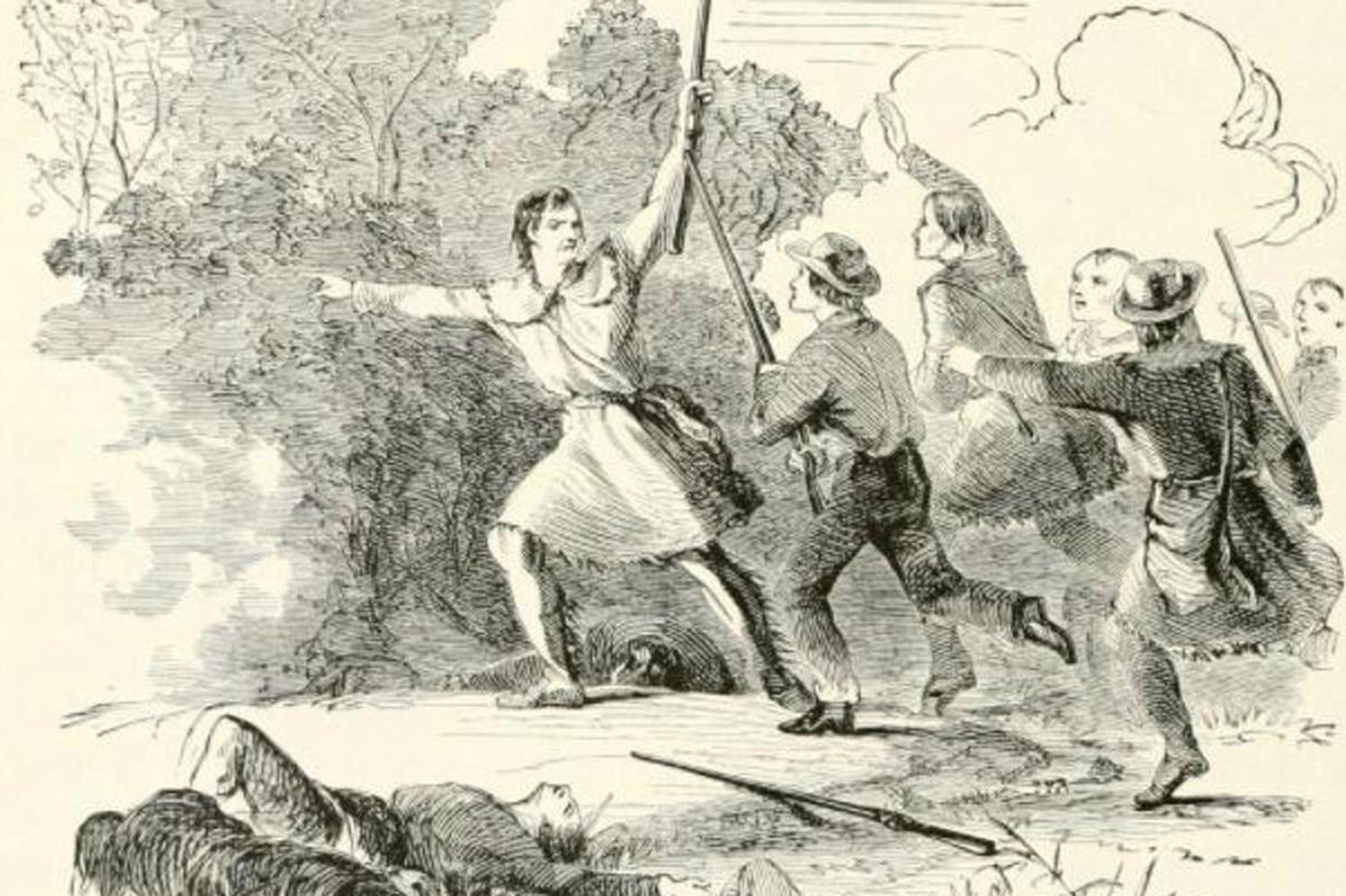

In August 1782, Loyalist Captain William Caldwell led three hundred warriors into Kentucky and attacked Bryan’s Station. Caldwell’s men could do little against the palisaded walls of the stockade and withdrew towards the Ohio when they learned of the approach of a relief force led by Colonel John Todd and Lieutenant Colonel Daniel Boone. The Kentuckians surprisingly caught up with Caldwell at a river crossing known as Lower Blue Licks, but Daniel Boone sensed an ambush. A hotheaded Major named Hugh McGary accused Boone of cowardice, jumped on his horse, and yelled for all to hear, “Them that ain’t cowards follow me.”

Tom Hand, creator and publisher of Americana Corner, explores how the Battle of Blue Licks became the worst defeat suffered by Americans west of the Appalachians during the Revolutionary War, and why it still matters today.

Images courtesy of The New York Public Library, Library of Congress, Commonwealth of Kentucky, Kentucky Historical Society, University of Kentucky, Wikipedia.

The American Revolution was winding down in the second half of 1782, with peace negotiations being conducted in earnest in Europe. But those talks appeared to have little impact on the actions of the main antagonists, as both sides were preparing invasions to punish their adversary.

Although Lord Charles Cornwallis surrendered to General George Washington at Yorktown in October 1781 and peace talks began in Europe soon thereafter, the brutal warfare in the Ohio Country and Kentucky continued unabated. Little did talks taking place in comfortable parlors thousands of miles away affect the Indians and Kentuckians, they were dealing with a daily dose of life and death affairs on the frontier.

With the capture of Fort Sackville, Kaskaskia, and Cahokia, Lieutenant Colonel George Rogers Clark had gained control of the southwestern portion of the Province of Quebec, better known as the Illinois Country, for the United States. Clark was at the height of his popularity, but the ambitious twenty-six year old wanted more and turned his attention to the crown jewel of British possessions in that part of the world, Fort Detroit.

By the end of 1765, peace was reached with the tribes who had participated in Pontiac’s rebellion, but all parties recognized this peace was tentative and temporary at best. The British colonist’s insatiable appetite for land and the Indians' need for huge swaths of unsettled wilderness for hunting were two incompatible desires.

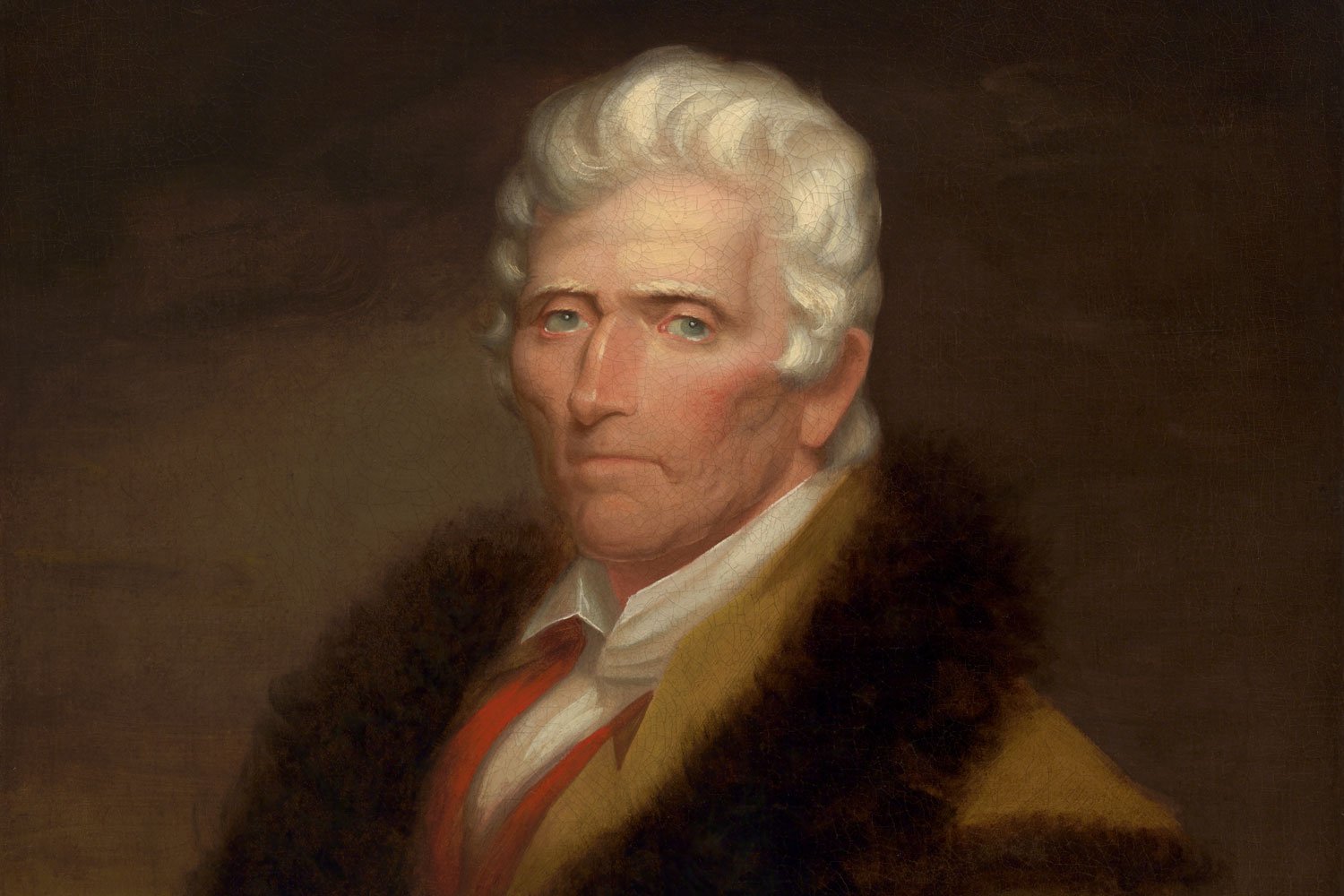

Soon after the American Revolution began in 1775, Daniel Boone joined the Virginia militia of Kentucky County (later Fayette County) and was named a captain due to his leadership ability and knowledge of the area. Over the next several years, Boone would participate in numerous engagements.

One of the greatest American explorers from our founding era was Daniel Boone. A legendary woodsman, Boone helped to make America’s dream of westward expansion in the late 1700s a reality.

The Wilderness Road, running from northeast Tennessee through the Cumberland Gap, was the main thoroughfare for Americans heading west into the new promised land of Kentucky from 1775 to about 1820. The pathway, blazed by Daniel Boone, was our nation’s first migration highway, but the trip was not for the faint of heart.

Americans have always had a yearning to move west and discover new lands. Along the way, our ancestors had to overcome many daunting natural barriers, the first of which was the Appalachian Mountains. The Wilderness Road through the Cumberland Gap was our nation’s first pathway through this formidable range.

With British fortune in the American Revolution at low tide in 1779, King Carlos III of Spain and his chief minister Jose Monino, Count of Floridablanca, decided the time was right for Spain to enter the war. But, for strategic reasons, they did not do so as a formal ally of the United States, but rather as one of France, their neighbor and cousin. As time would tell, Spain’s decision was instrumental in securing American independence.