Lord Dunmore’s War

By the end of 1765, peace was reached with the tribes who had participated in Pontiac’s rebellion, but all parties recognized this peace was tentative and temporary at best. The British colonist’s insatiable appetite for land and the Indians' need for huge swaths of unsettled wilderness for hunting were two incompatible desires.

Despite numerous agreements, especially the Royal Proclamation of 1763 which put a temporary hold on British settlement west of the Appalachians, incidents still occurred with great frequency. Most of these confrontations were between the natives and explorers and surveyors sent to lay out future settlements. Shawnee, Miami, and other tribes north of the Ohio resented these men they viewed as intruders and the implication that more settlers were coming into the fertile territory of Kentucky, their traditional hunting grounds.

To quell the violence, British officials met with Indian leaders to sign yet more treaties despite the proven futility of these agreements. Because the Indians were fiercely independent and each warrior made his own decisions, treaties signed by one group had little bearing on other braves, even if they were from the same tribe. Additionally, multiple tribes often laid claim to the same territory, as was the case in Kentucky.

To further confuse the matter, the predominant tribes in the Ohio Country (Shawnee, Mingo, and Delaware) were not native to the area. In most cases, they had not lived in the region much longer than the British colonists but were allowed to live there by the Iroquois who had driven them from their homelands further east.

In any event, in October 1768, British and Cherokee leaders signed the Treaty of Hard Labour which relinquished most of present day West Virginia to the British. One month later, Sir William Johnson, the Superintendent of Indian Affairs for the Northern Department, met with leading chiefs of the Iroquois nation and signed the Treaty of Fort Stanwix by which the Iroquois essentially ceded this exact same territory to the Brits.

Part of the issue with signing treaties with the Native Americans was that their idea of land ownership was quite different from the European concept. In the Native world, there were no deeds or documents, and nothing was recorded at City Hall. Even between the numerous tribes there was no agreement as to who owned what or who had the authority to sign away land rights. On countless occasions, chiefs of one tribe might give away territory while other chiefs of the same tribe would deny they had the right to do so.

When Europeans tried to establish land ownership with Native Americans based on western legal concepts, they were on a fool’s errand. For time immemorial, Native Americans had followed the simple doctrine of “right of conquest.” All tribes understood that whatever you could take and hold was yours, until a stronger power took it away. In any event, these treaties were not a permanent solution.

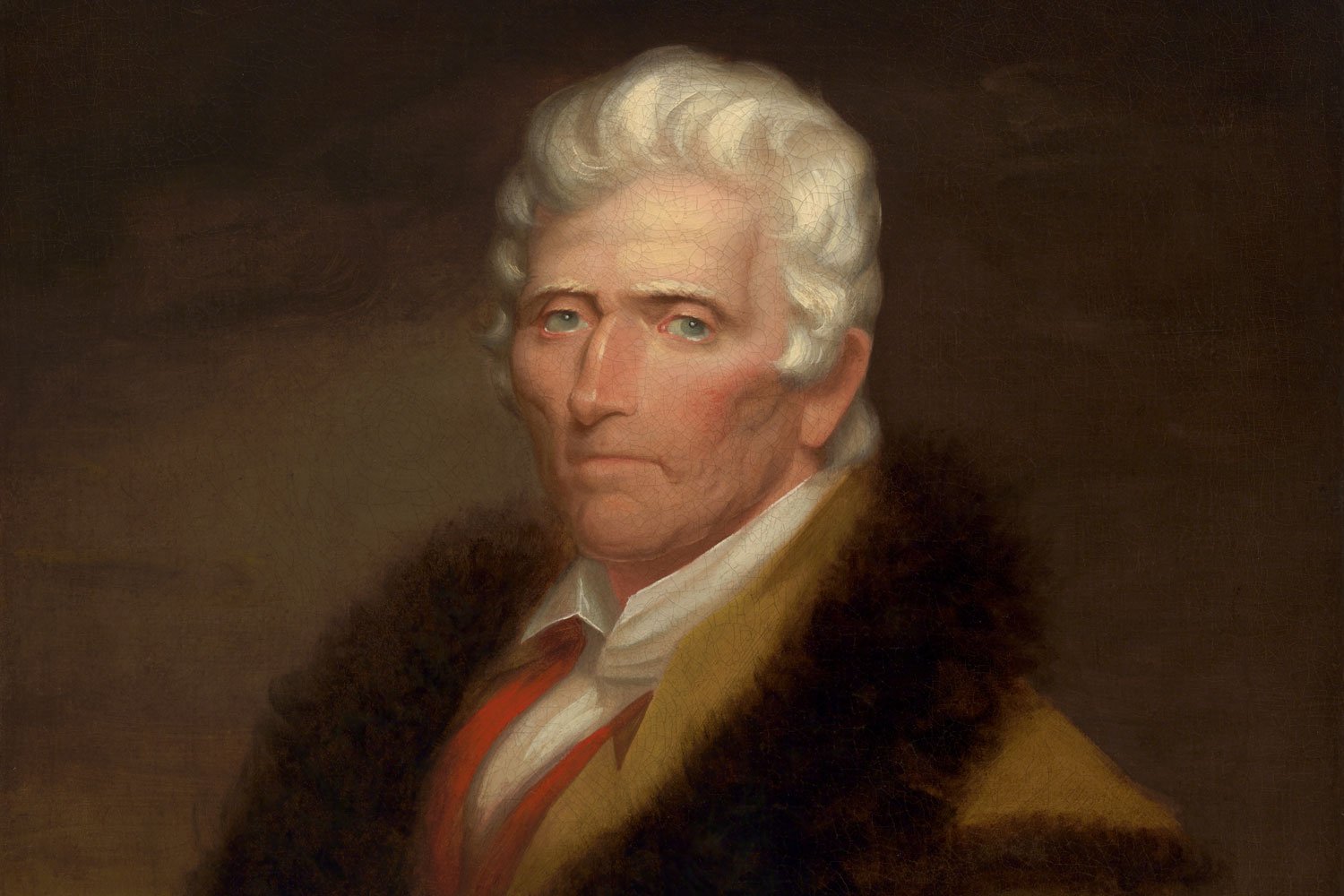

Chester Harding. “Daniel Boone.” National Portrait Gallery, Smithsonian Institution.

Over the course of the next few years, more and more settlers moved into the Ohio Country, and bloody attacks occurred on a regular basis, mostly on small surveying parties. Then, in September 1773, Daniel Boone, an experienced but still relatively unknown explorer, led fifty settlers, including his entire family, into the disputed territory hoping to establish the first settlement in Kentucky.

Boone sent a small detachment, including his son James, back to purchase additional supplies. The group was ambushed just south of the Cumberland Gap by a band of Cherokee, Delaware, and Shawnee who killed and badly mutilated several men, including James Boone. An account of the incident in all its gory detail made its way back east into the major newspapers, and colonists, especially those in Virginia, demanded action be taken to punish those responsible and secure the frontier.

The Royal Governor of Virginia at the time was John Murray, Earl of Dunmore, born in Scotland in 1730. William Murray, John’s father, had supported the ill-fated rebellion of Bonnie Prince Charlie and was imprisoned when the rising was crushed at the Battle of Culloden Moor in April 1746. Two years later, King George II pardoned William which allowed John to join the British army as a young Captain. When his father died in 1756, John succeeded him and became the fourth Lord Dunmore. After serving one year as the Governor of New York, Dunmore was promoted to the Virginia governorship.

In 1774, Lord Dunmore launched two expeditions into the Ohio Country, one of which he personally led from Fort Pitt down the Ohio in late September. The other contingent commanded by Colonel Andrew Lewis departed from Camp Union, near present day Lewisburg, WV, on September 6 and moved down the Great Kanawha River. The two armies were to link up where the Kanawha emptied into the Ohio at a place called Point Pleasant, and then proceed deep into the Shawnee homeland, destroying all villages they encountered.

Lewis, a veteran of the French and Indian War, and his 800-man army first marched to the Elk River, eighty-five miles from Camp Union, where they established a camp that would act as an intermediate supply depot for expedition. Completing that precautionary step, Colonel Lewis proceeded to the rendezvous spot, Point Pleasant, arriving on October 6. While Lewis began preparing for the next phase of the expedition north of the Ohio, a talented Indian chief named Cornstalk was preparing a surprise for the Virginians.

Next week, we will discuss the Battle of Point Pleasant and the conclusion of Lord Dunmore’s War. Until then, may your motto be “Ducit Amor Patriae,” love of country leads me.

Commodore Edward Preble assembled his considerable American fleet just outside Tripoli harbor in August 1804, determined to punish the city and its corsairs, and force Yusuf Karamanli, the Dey of Tripoli, to sue for peace.