The Election of 1800

The presidential election of 1800 was one of the most controversial and consequential in the history of the United States. It represented a true changing of the guard as the Federalist party of Washington, Hamilton, and Adams gave way to the Democratic-Republican ideals of Jefferson and Madison and took the United States in a different direction for a generation to come.

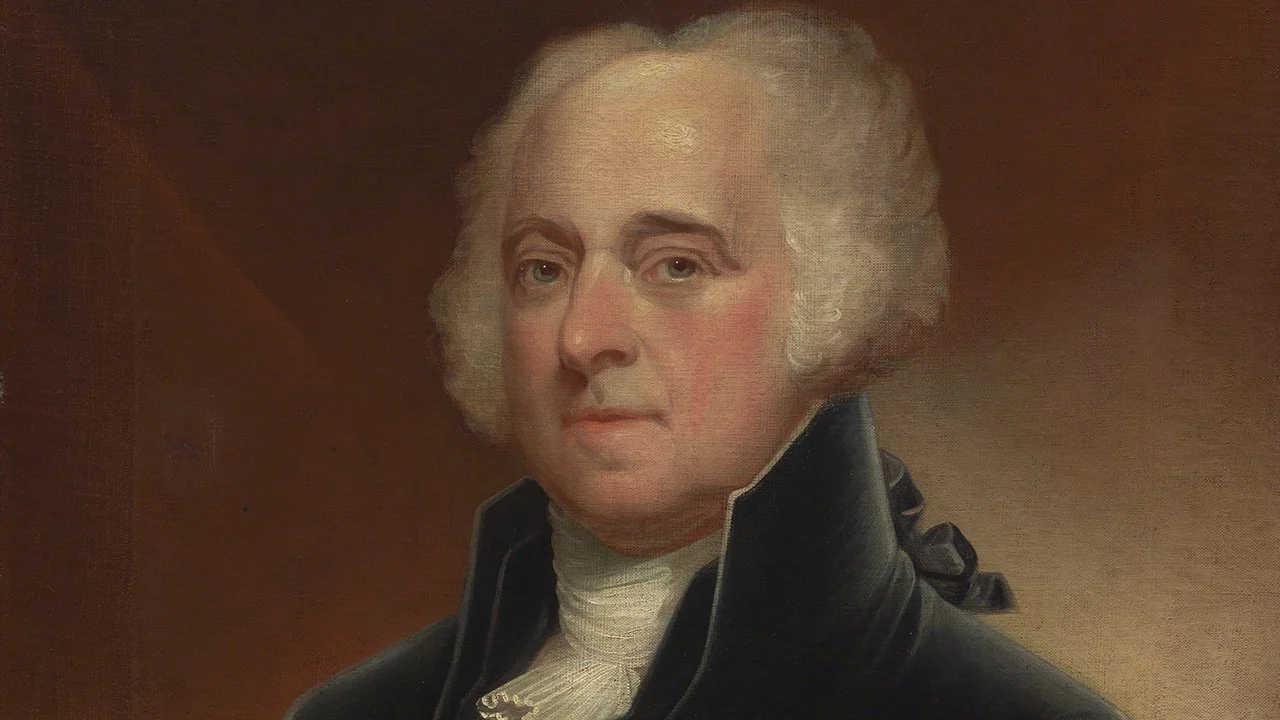

The Legacy of John Adams

John Adams’s loss to Thomas Jefferson in the presidential election of 1800 was a great disappointment for Adams and marked the end of the public life of this devoted patriot. For a quarter of a century, Adams had been serving at the center of the fight to create and establish the country he loved. By all accounts, he arguably did more to shape the United States than any other Founding Father, except for the incomparable George Washington.

The End of the Quasi-War

n November 1799, Napoleon Bonaparte took over control of the French government with the support of wealthy French merchants who owned lucrative plantations in the Caribbean. Bonaparte was anxious to conclude the Quasi-War, which sapped France’s naval resources and harmed his supporters’ economic interests. The determination of President Adams to stand by his principles, certainly one of his greatest traits, and not expand the conflict with France benefitted the country. But it cost Adams politically as the President lost the support of his own party. By the time the news of the treaty reached America, it was too late to help him in the election of 1800, which he lost to Thomas Jefferson.

The Quasi-War with France

The Quasi-War was an undeclared naval war between France and the United States, fought primarily in the Caribbean and the southern coast of America, between 1798 and 1800. The war resulted from several disagreements with France but was mostly due to French privateers seizing American merchant ships. On April 30, 1798, Congress created the Department of the Navy and appropriated funds to finish six frigates that had been authorized by the Naval Act of 1794. Three were near completion and soon put to sea, and three more followed in the next two years. On July 7, Congress authorized this new United States Navy to begin seizing French ships, marking the “official” start of the Quasi-War.

Relations with France Fall Apart

America’s first armed conflict following the American Revolution was a mostly forgotten fight with France called the Quasi-War and was the culmination of a series of disagreements with our former ally. In 1793, to avoid getting drawn into the latest war between Great Britain and France, President George Washington issued his Proclamation of Neutrality. This declaration angered the French because they considered Washington’s refusal to help them as a violation of the 1778 Treaty of Alliance.

The Kentucky and Virginia Resolutions

In response to the Alien and Sedition Acts passed by the Federalist-controlled Congress in July 1798, Democratic-Republicans howled long and loud about the legislation that they viewed as an assault on both their party and the Constitution. They immediately turned to their leader, Vice President Thomas Jefferson, to counter these acts and, if possible, turn them to their political advantage. Jefferson enlisted the support of James Madison, his fellow Virginian and brilliant political protégé. The two men created their rebuttals separately with Jefferson’s version being fairly radical, while Madison drafted a more balanced argument against the acts.

The Alien and Sedition Acts

In 1798, worried that emotions would push France and America into an open war, President John Adams sent a delegation consisting of John Marshall, Elbridge Gerry, and Charles Cotesworth Pinckney to Paris to try and calm these rising tensions. The delegation arrived in Paris in early October but were denied a meeting for weeks. They were finally approached by three French officials whose code names were X, Y, and Z. These Frenchmen informed the Americans that before any negotiations could start, a few “sweeteners” would need to be provided to French officials, including $250,000 for Foreign Minister Charles Talleyrand.

The XYZ Affair

In 1798, worried that emotions would push France and America into an open war, President John Adams sent a delegation consisting of John Marshall, Elbridge Gerry, and Charles Cotesworth Pinckney to Paris to try and calm these rising tensions. The delegation arrived in Paris in early October but were denied a meeting for weeks. They were finally approached by three French officials whose code names were X, Y, and Z. These Frenchmen informed the Americans that before any negotiations could start, a few “sweeteners” would need to be provided to French officials, including $250,000 for Foreign Minister Charles Talleyrand.

The Rise of John Adams

John Adams was one of America’s greatest patriots from the founding generation and may have contributed more to America gaining her independence than anyone other than George Washington. Upon graduation from Harvard in 1755, Adams taught school for one year but soon began to study law and was admitted to the Massachusetts bar in 1759. After Parliament passed the Stamp Act in 1765, Adams joined the American cause and began a long battle to protect the rights of his fellow colonists.

The Election of 1796

The first contested United States presidential election took place in the fall of 1796, pitting Thomas Jefferson against Vice President John Adams. Arguably, no presidential election in the country’s history has ever featured a choice between two such American titans. Jefferson was the leader of the Democratic-Republicans who were pro-French and favored strong states’ rights. Adams was the favorite son of the Federalist Party that was pro-British and favored a strong central government. For the most part, the election split along geographic lines with Adams capturing the north and Jefferson the southern states, plus Pennsylvania.

The Legacy of George Washington

No man has had a greater impact on the United States than George Washington. This quintessential American carried the country through eight long years of the American Revolution and devoted another eight years to establishing the new constitutional government as its first president. Washington was one of those rare individuals who seemed destined, almost from birth, for greatness.

Washington’s Farewell Address – Debt and Foreign Entanglements

George Washington’s Farewell Address begins with the words In his Farewell Address, President George Washington advised America to remain fiscally prudent and to avoid permanent foreign alliances that could pull the country into a costly war. Washington understood that in times of war the nation must incur unforeseen expenses, but he felt America should avoid “the accumulation of debt, not only by shunning occasions of expense, but by vigorous exertions in time of peace to discharge the debts.” But Washington’s most stringent warning was on the danger of establishing binding alliances with other countries.

Washington’s Farewell Address – The Need for Unity

George Washington’s Farewell Address begins with the words “Friends and fellow citizens,” as the President was addressing his words to the people, the true source of sovereignty in America. Washington discusses the need for America to stay united and states that the “Unity of government…is a main pillar in the edifice of your real independence, the support of your tranquility at home; your peace abroad; of your safety; of your prosperity; of that very Liberty, which you so highly prize.”

Washington’s Farewell Address – The Background

President George Washington’s Farewell Address is one of our nation’s greatest documents. It was not really an address but rather a letter written by President Washington to his fellow citizens and first published in Claypoole’s American Daily Advertiser on September 19, 1796, near the end of his second term.

The Battle of Fallen Timbers

Following St. Clair’s disaster at the Battle of the Wabash, a reluctant Congress finally agreed to President George Washington’s request to create a force capable of conquering the Northwest Territory. The result was a 5,000-man force called the Legion of the United States, the forerunner of today’s Army. Washington entrusted its command to General Anthony Wayne, a trusted officer from the American Revolution. In July 1794, following countless delays, General Wayne began his final thrust into the Shawnee’s heartland, searching for the large Indian force he knew awaited him.

St. Clair’s Debacle on the Wabash

Following General Josiah Harmar’s defeat in October 1790, Congress expanded the army and President George Washington appointed Arthur St. Clair, governor of the Northwest Territory, to command the new force. In September 1791, St. Clair began his march north from Fort Washington with 1,500 poorly trained and under equipped men. Despite several soldiers being killed and numerous horses stolen, St. Clair did not believe any large Indian force was nearby. Disregarding these warning signs, he did not post any picket lines that night nor did he have the men fortify their positions. At dawn on November 4, 1,000 warriors, led by Little Turtle and Blue Jacket, launched a surprise attack on the American camp.

Settling the Ohio Frontier

In the 1780s, American pioneers began moving into the Ohio frontier and met resistance from Indian tribes who claimed the land as their own. The clash between these two disparate cultures resulted in the Northwest Indian War, the first war ever fought by the new constitutional government. Determined to protect the pioneers and encourage settlement, President Washington tried to purchase land from the tribes rather than committing to an expensive war. In January 1789, Territorial Governor Arthur St. Clair convinced several chiefs to sign the Treaty of Fort Harmar, which essentially ceded all of Ohio to the United States. But the Shawnee, encouraged by promises of British support, refused to sign the treaty or acknowledge its legitimacy.

The Northwest Ordinance of 1787

The Northwest Ordinance was one of the United States most important founding documents, only less significant than the Declaration of Independence and the Constitution. The act, passed by the Confederation Congress on July 13, 1787, created the Northwest Territory and a framework for the country’s territorial expansions. The Northwest Territory had been part of Canada until conquered by George Rogers Clark during the American Revolution. It comprised 300,000 square miles, stretching from the Appalachians to the Mississippi and from the Great Lakes to the Ohio.