War of 1812, Part 4: British Invade Ohio

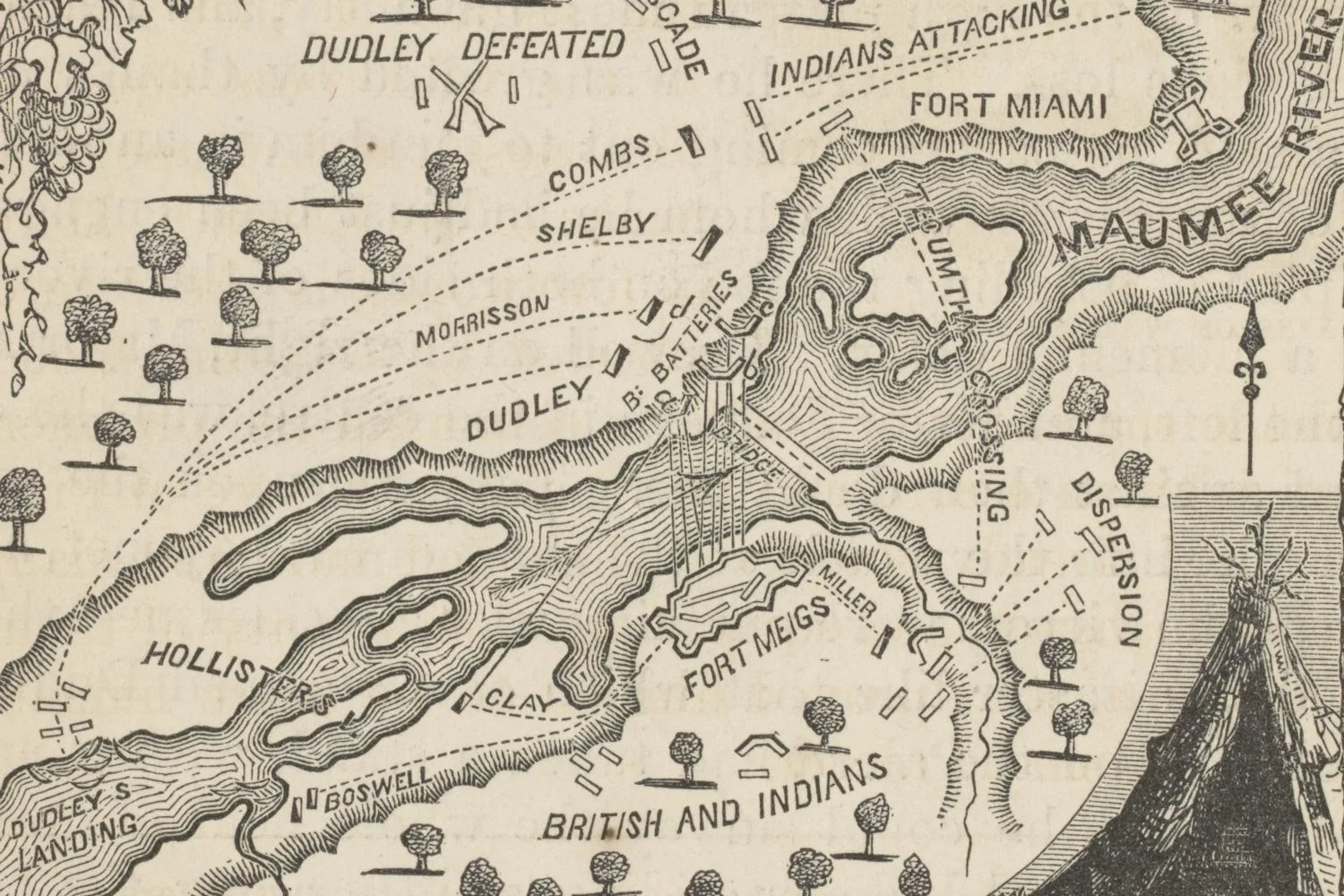

Following the American disaster at Frenchtown, General William Henry Harrison, gathered another force to turn the tide in the west. In February, Harrison tasked Major Eleazer Wood to construct Fort Meigs on the banks of the Maumee River. On May 1, a British army including 1,000 regulars and militia under General Henry Proctor and 1,500 Indians led by Tecumseh initiated a siege of Fort Meigs. After pounding the fort with artillery for four days, Proctor sent in a demand that Harrison surrender the fort or face the consequences. Despite outnumbering the Americans, Proctor lost heart and abandoned the siege, retreating to Fort Malden. But he returned to Fort Meigs in July with a larger force including 400 regulars and 3,000 Indians. After failing to lure the Americans from the safety of the fort, Proctor called off the attack and took his force up the Sandusky River to Fort Stephenson which appeared to be an easier target.

War of 1812, Part 3: Debacle on the River Raisin

Following the surrender of Detroit, William Henry Harrison, governor of the Indiana Territory, was named as Hull’s replacement. Harrison consolidated his army at the Maumee Rapids and planned to move on Detroit in the spring. But in mid-January 1813, General James Winchester, one of Harrison’s officers, received word that Frenchtown, a small village thirty miles north on the River Raisin, was in danger of being attacked. Although Harrison had instructed Winchester not to advance beyond their base camp, Winchester felt compelled to respond. Winchester laid out his camp with Kentucky militiamen behind a split rail fence on the left but the regulars on the right were completely exposed with no cover to their front. Importantly, Winchester failed to send out scouts to keep an eye on the British. Undetected by the Americans, the British attacked at dawn on January 22.

War of 1812, Part 2: The Surrender of Detroit

President James Madison named William Hull, governor of the Michigan Territory, to command the western war effort in the War of 1812. Hull’s primary mission was to capture Fort Malden, the main British outpost in the region. Hull’s task was formidable for several reasons, but primarily because his supply line stretched for 200 trackless miles through hostile Indian country. Hull arrived at Detroit on July 5 and, one week later, crossed his army into Canada and moved south to capture Fort Malden. While waiting for his field guns to arrive to commence the assault, Hull received the disturbing news that Fort Mackinac had been captured by the British, meaning that several thousand Indians who had participated in that attack would soon be coming down from the north. On August 15, General Isaac Brock, governor of Ontario, appeared with 1,500 men on the opposite bank of the Detroit River and demanded Hull’s surrender.

War of 1812, Part 1: A Divided America Goes to War

In June of 1812, President James Madison asked Congress to declare war on Great Britain for refusing to honor American maritime rights. Madison’s hand was forced by the young firebrands who made up the Twelfth Congress. Support for the war was not unanimous, as New England, dominated by Federalists, strongly opposed the conflict. But to the Democratic-Republicans, Canada seemed an easy conquest, with Thomas Jefferson stating that “the acquisition of Canada…will be a mere matter of marching.” When the vote on Madison’s request was taken on June 18, 1812, it was the closest in our country’s history on a declaration of war.

Road to War, Part 10: The Battle of Tippecanoe

On September 24, 1811, General William Henry Harrison, governor of the Indiana Territory, led an army north from the territorial capital of Vincennes. His objective was to break up a large gathering of Indians that were part of a confederacy organized by Tecumseh to resist American settlement in the Ohio Country. Although advised by his officers to immediately strike the village, Harrison was under strict orders from Secretary of War William Eustis to maintain peace if possible and not initiate an attack. Tecumseh happened to be away recruiting southern tribes for his confederacy so the responsibility for dealing with the American army fell to the Prophet. Although prior to leaving Tecumseh had stressed that a battle was to be avoided at all costs, the Prophet felt he must do something.

Road to War, Part 9: Tecumseh and the Prophet

Tecumseh’s War was the last great Indian war in the Northwest Territory and raged from 1811 to 1817. Tecumseh was a Shawnee born in 1768 in today’s central Ohio. By the late 1780s, Tecumseh began participating in raids into Kentucky and fought at the 1794 Battle of Fallen Timbers. Despite Tecumseh’s prowess, he may have remained unknown to history were it not for his brother Tenskwatawa, better known as the Prophet, who rose to prominence in 1805 following a series of visions. Part of the reason why the Prophet’s message resonated so well with Indians in the Great Lakes region was their growing frustration over repeated land cession treaties between willing chiefs and the United States.

Road to War, Part 8: The Fifty-Year War for the Old Northwest

At the conclusion of the French and Indian War in 1763, the British gained possession of all French lands in North America, including the Northwest Territory, which was then part of Canada. Unlike the French who allied themselves with the Indian nations, the British treated the natives as a conquered people and for the next fifty years there was continuous conflict between white settlers and Indians in this region.

Road to War, Part 7: Madison Changes Sides

In February 1789, James Madison was elected to the House of Representatives for the first Congress under the Constitution. Besides leading the House, Madison helped shape the Washington administration, drafting President Washington’s inaugural address and recommending Alexander Hamilton for Secretary of the Treasury and Thomas Jefferson for Secretary of State. But a break soon developed between the Madison-Jefferson faction, known as Democratic-Republicans, and Washington’s Federalist administration over Hamilton's plan for the national government to assume state debt incurred during the war.

Road to War, Part 6: James Madison, Father of the Constitution

In 1787, James Madison and Alexander Hamilton organized the Constitutional Convention not simply to fix flaws in the Articles of Confederation but rather to create a new vibrant national government under which the United States could flourish. The most critical issue to be resolved was how representation in Congress would be determined, for with more representatives came more power. Madison’s Virginia Plan comprised fifteen resolutions that became the basis for our constitution and called for representation according to population in both the House and the Senate. After the convention, Madison, along with Alexander Hamilton and John Jay, drafted eighty-five essays known as The Federalist Papers, the greatest collection of writings ever on a federal constitutional government. No other Founding Father played such an outsized role in creating our nation’s Constitution.

Road to War, Part 5: James Madison Embraces the American Cause

In 1774, Parliament passed the Coercive Acts, which effectively shut down the city of Boston and revoked the historic charter of Massachusetts, replacing it with royal authority. This affront to the liberties of American colonists greatly troubled Madison and pushed him into the camp of American separatists, and it was here that Madison found his true calling and to which he would devote the rest of his life. Madison was elected to the Confederation Congress, where his brilliant mind and extraordinary work ethic soon gained the young Virginian the admiration of his fellow congressmen and made him a leader in the national assembly.

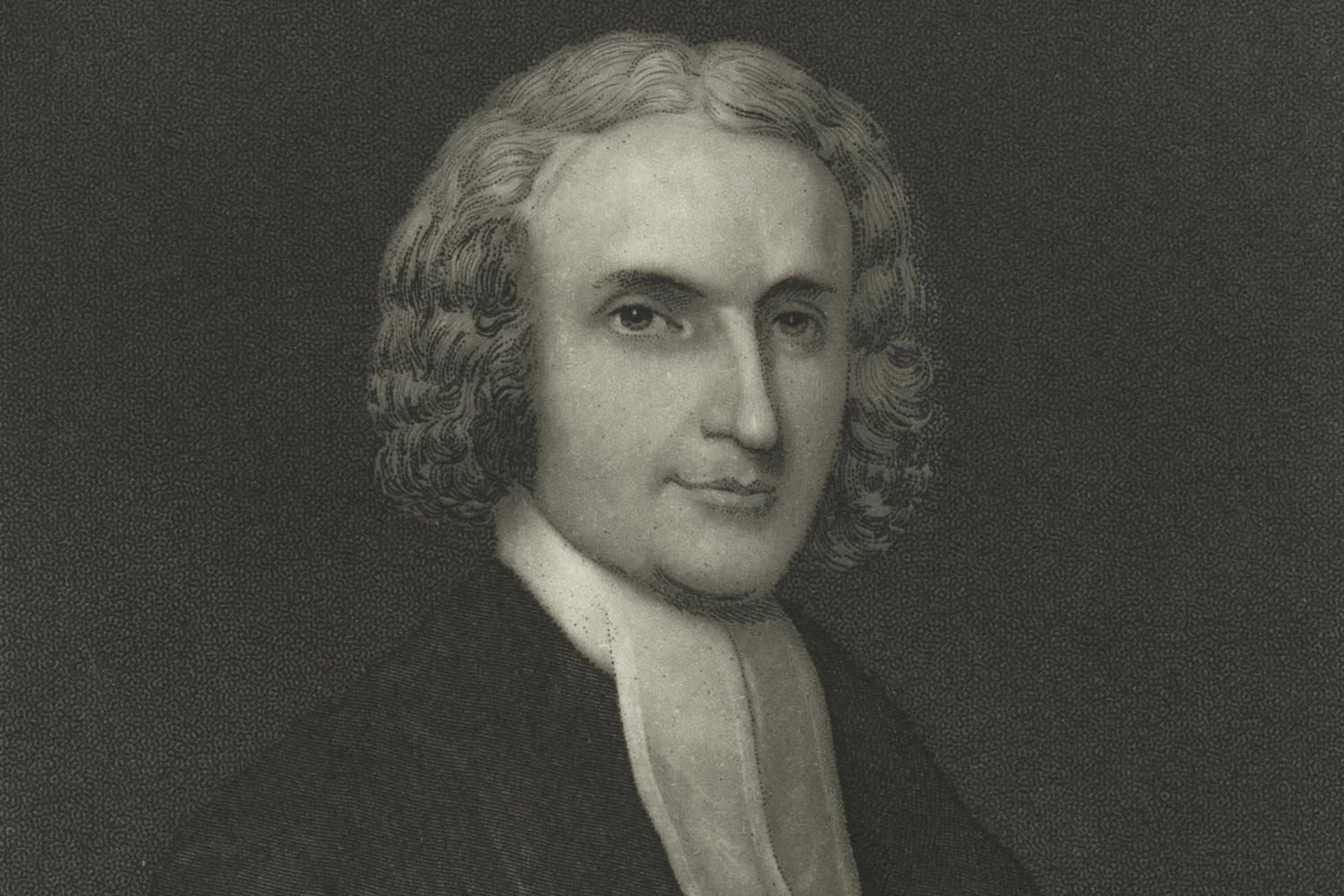

Road to War, Part 4: The Early Life of James Madison

James Madison was one of our nation’s most important founding fathers and played a critical role in the shaping United States. Known to history as the “Father of the Constitution,” Madison’s brilliant mind was among the finest the nation has ever produced and his grasp of the theories of republican government and his efforts to implement those theories were unparalleled.

Road to War, Part 3: President Jefferson Declares Economic War

When the Democratic-Republicans came to power in 1800, the Jefferson administration effectively shut down and disbanded both the United States Army and Navy. As a result, when American merchant ships were illegally seized as contraband of war by both the British and the French during the Napoleonic wars, the United States was helpless to respond. Consequently, President Jefferson, who was philosophically opposed to war, decided to strike back economically rather than militarily.

Road to War, Part 2: The Chesapeake-Leopard Affair

In June 1807, several British sailors deserted from Royal Navy ships stationed near Norfolk, Virginia, and signed on with the USS Chesapeake, a 50-gun frigate commanded by Captain James Barron that was preparing to sail to the Mediterranean. Admiral George Berkeley, who commanded the British fleet in North American waters, was frustrated at the repeated desertions and sent word via the British frigate Leopard, commanded by Captain Salusbury Humphreys, to the British squadron to detain and search the Chesapeake for deserters. On the morning of June 22, Captain Humphreys had a message delivered declaring that there were deserters on board the Chesapeake and requesting permission to inspect the crew. Captain Barron denied the request, and the Leopard then fired two warning shots across the bow of the Chesapeake. Two minutes later, the Leopard poured a full broadside of solid shot and canister at point blank range into the helpless American frigate.

Road to War, Part 1: The Causes of the War of 1812

The War of 1812 has been called the “second American Revolution,” but the facts do not fully support that assertion. It is true that in both cases America’s enemy was Great Britain and the main catalyst that took us to war was American anger resulting from British transgressions, but the road to this second fight between these two countries was largely an unintended consequence of the almost continuous war that raged from 1793 to 1815 between England and France.

American Judiciary, Part 11: The Legacy of John Marshall

John Marshall is arguably the most influential man in American history who was never elected president. For more than three and a half decades as the chief justice of the Supreme Court, Marshall oversaw the creation of the American judiciary and established that it is the responsibility of the courts to say what the law is. John Adams, who appointed Marshall as chief justice, stated, “my gift of John Marshall to the people of the United States was the proudest act of my life.” Marshall’s decisions seemed to always have a view towards establishing a strong central government and strengthening the bonds necessary to create a nation, building those ties that allowed our country’s disparate parts to function as one.

American Judiciary, Part 10: The Treason Trial of Aaron Burr

On May 22, 1807, Aaron Burr was brought before a grand jury in Richmond, Virginia, charged with committing treason against the United States. The prosecution’s star witness, General James Wilkinson, proved to be a liability as Wilkinson was forced to admit that he had forged a letter from Burr which was the prosecution’s main piece of evidence. Regardless, the grand jury, made up mostly of Democratic-Republicans, indicted Burr for treason, the only time in our country’s history when a President or Vice President has been indicted for this crime.

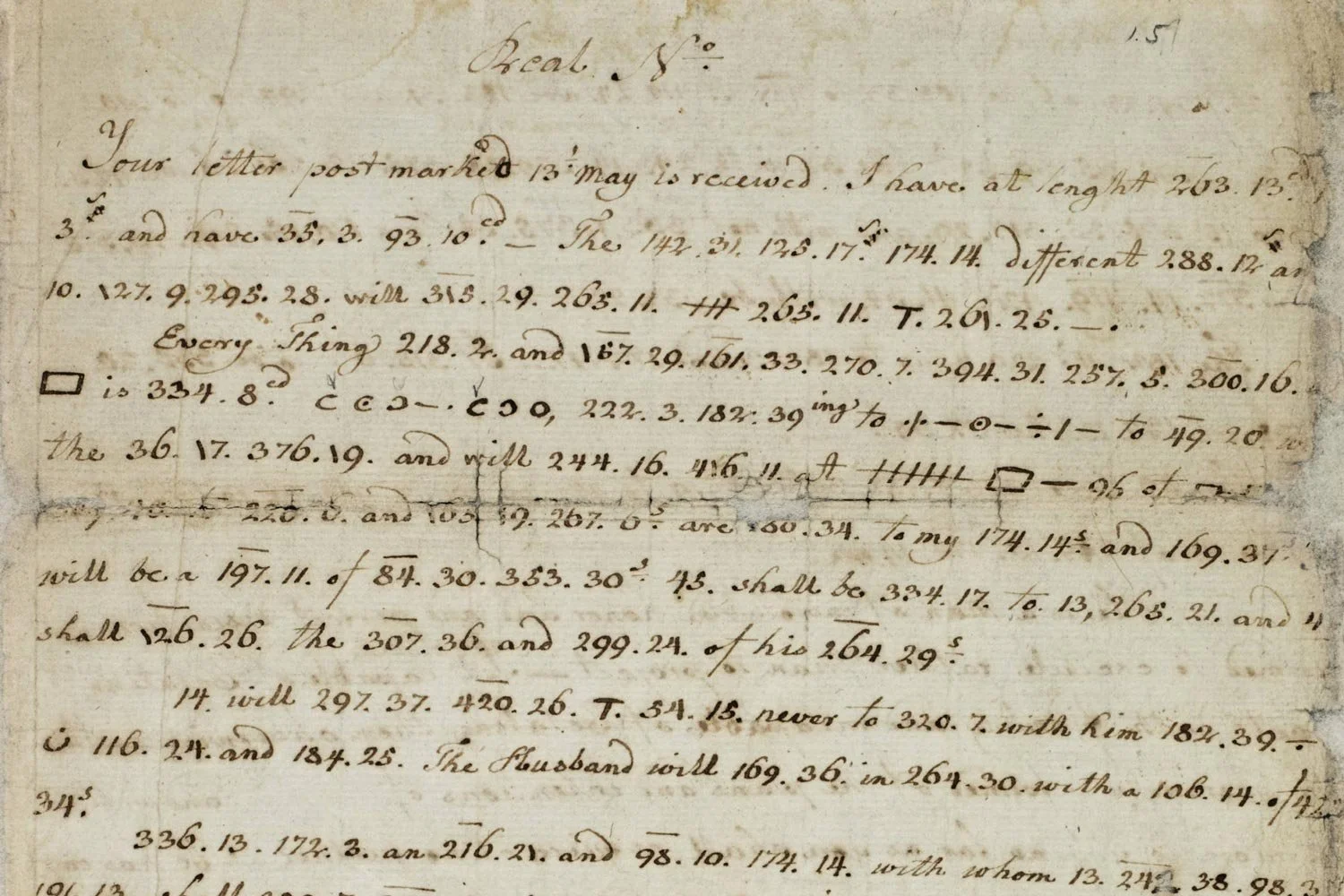

American Judiciary, Part 9: The Burr Conspiracy

In the presidential election of 1800, Aaron Burr and Thomas Jefferson tied for the most electoral votes, but Burr refused to stand aside for Jefferson. The House of Representatives ultimately selected Jefferson to be president and Burr vice president, but Burr’s decision to challenge Jefferson made him an arch enemy of the president and an outcast in the Democratic-Republican party. Upon leaving office in the spring 0f 1805, Burr was a ruined man, financially and politically, with his reputation in tatters.

American Judiciary, Part 8: The Impeachment of Samuel Chase

Samuel Chase is the only Supreme Court Justice in our nation’s history to be impeached and that occurred during a political tussle over the independence and power of the judiciary between President Thomas Jefferson and Chief Justice John Marshall. In March 1804, the House of Representatives, in a party line vote, approved eight charges of impeachment against Chase. The problem was that the Constitution states that civil officers like Supreme Court justices may only be removed for “Treason, Bribery, or other high Crimes and Misdemeanors” and Chase was not charged with any of these. But that was just the point; the Chase trial was part of a larger Democratic-Republican plan to reduce the power and independence of the judiciary.