Kentucky Under Assault

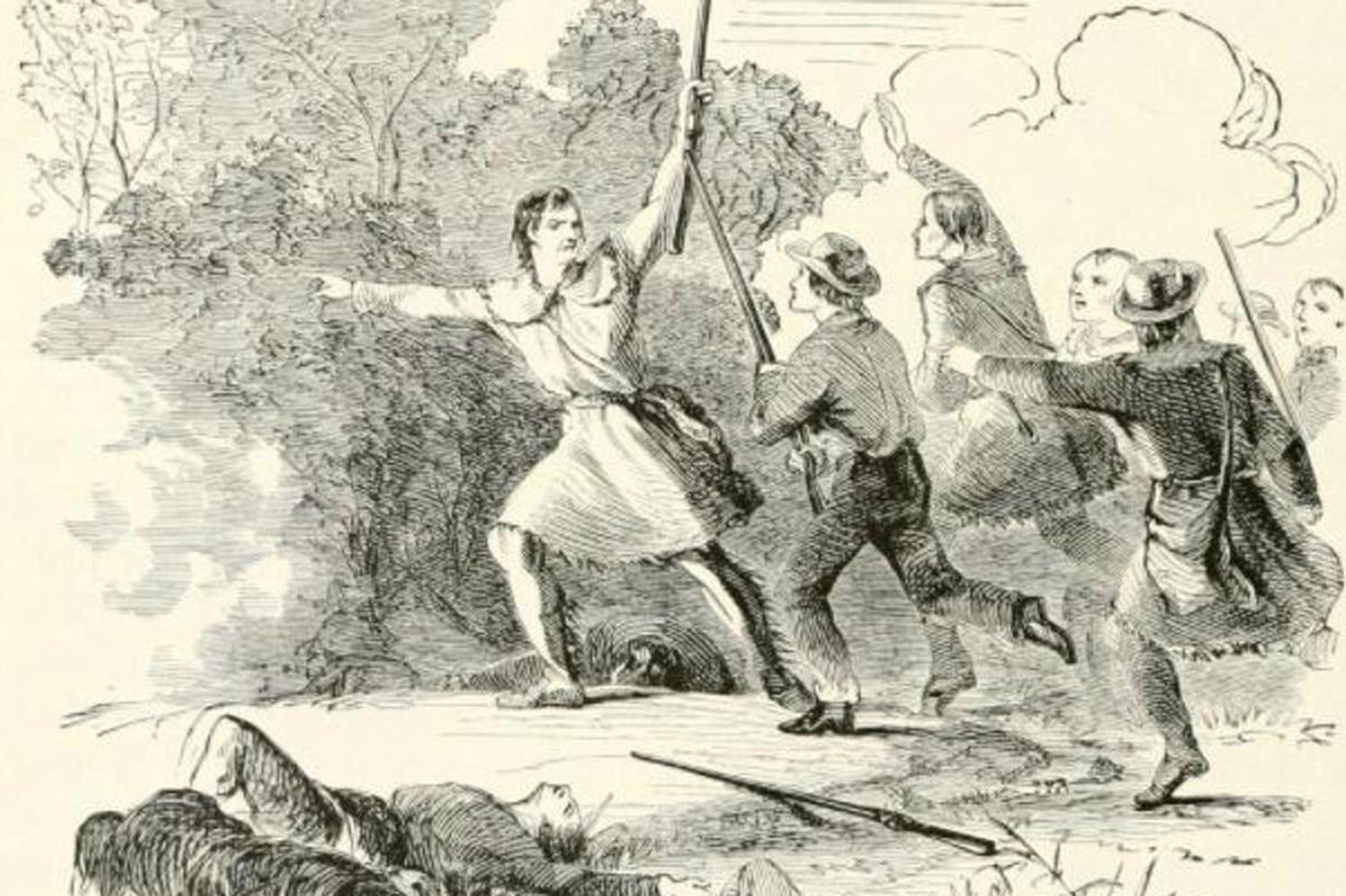

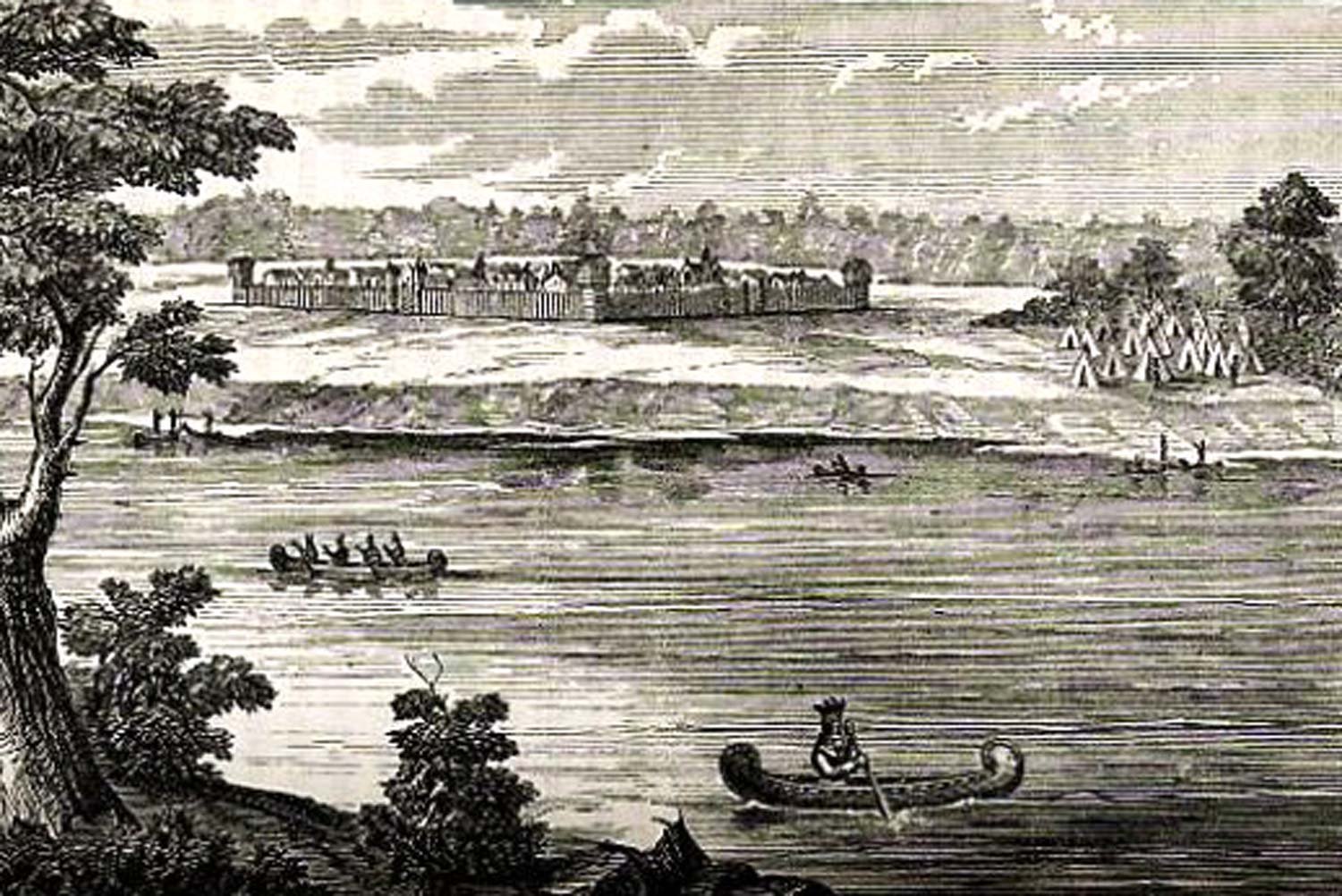

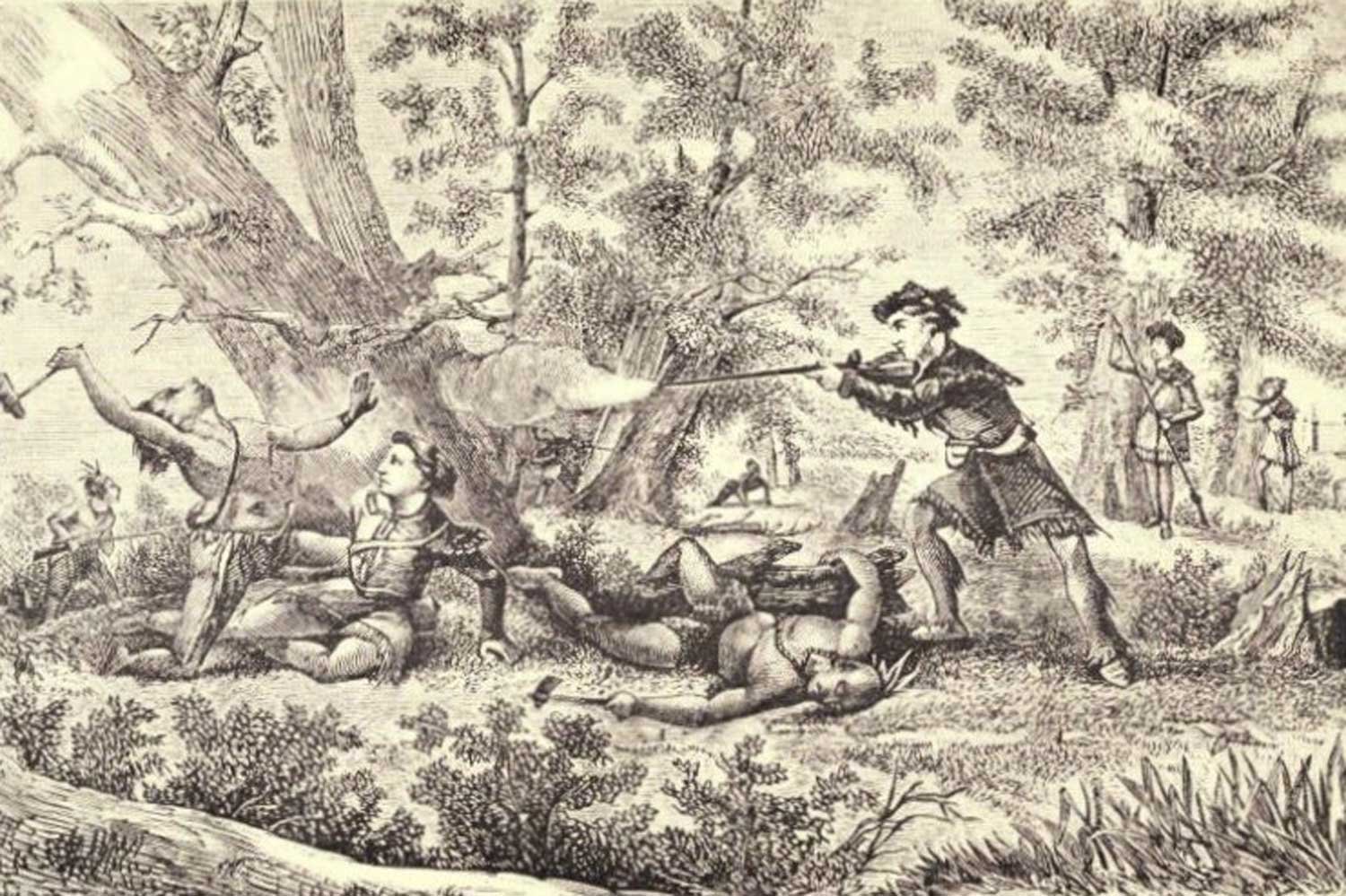

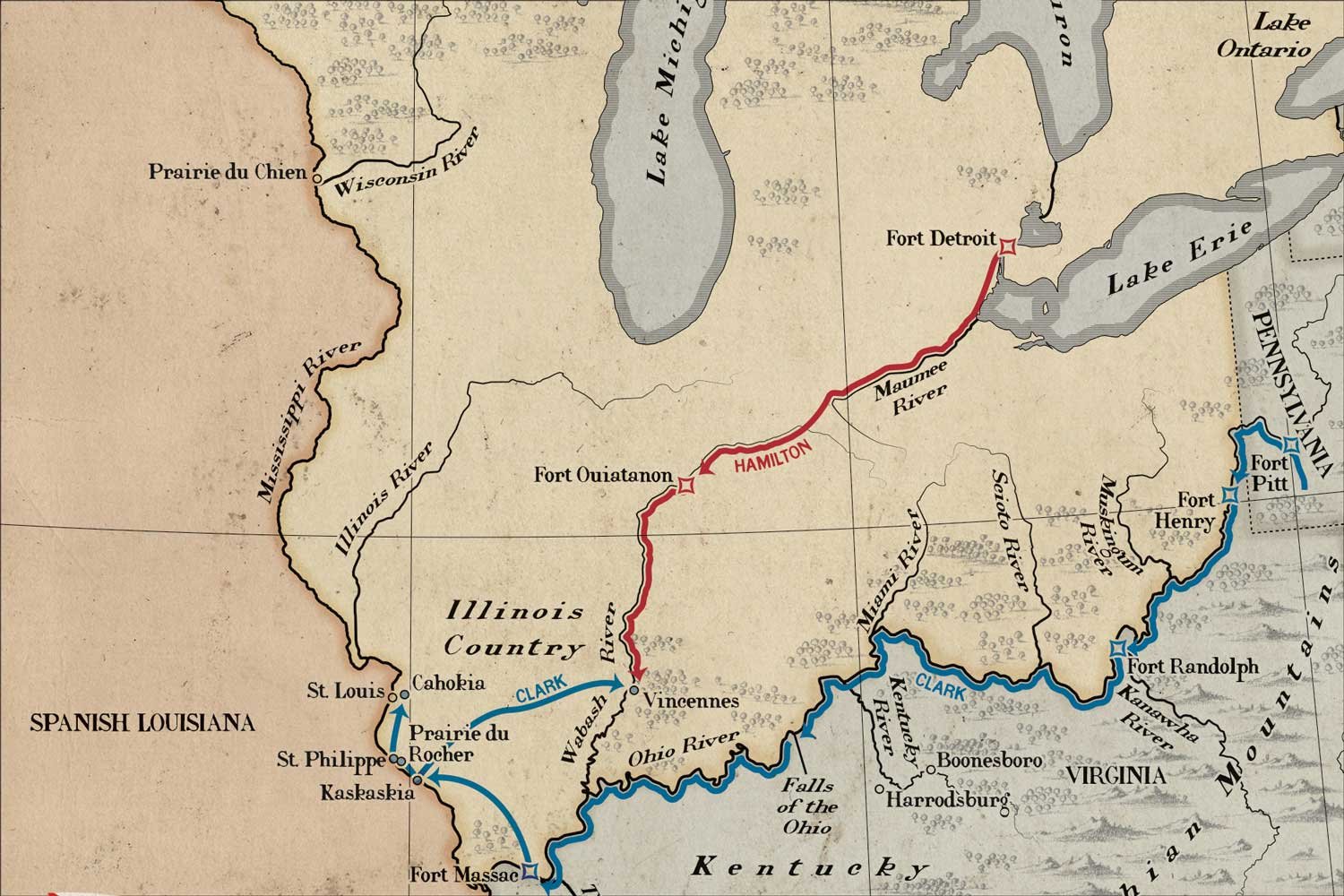

Since the attack on Logan’s Fort in May 1777, the settlements of Kentucky had been under constant assault by tribes north of the Ohio. In September 1778, Blackfish, a Shawnee chief, led a large contingent of warriors to Boonesboro. The siege lasted 12 days, but Daniel Boone’s efforts saved the post and Blackfish was forced to retire. In the spring of 1780, the British, in conjunction with their invasion of the southern colonies, launched an offensive to recapture the Illinois Country, but Colonel George Rogers Clark repelled that force near Cahokia on May 25. Clark’s army then crossed the Ohio in August and headed north into Shawnee territory to exact some revenge.

Tom Hand, creator and publisher of Americana Corner, explores how Kentuckians, under assault, took the fight into the Ohio Country, and why it still matters today.

Images courtesy of Library of Congress, Gilcrease Museum, Indiana State Library, University of South Florida, The New York Public Library, Encyclopedia Virginia, Wikipedia.

The Treaty of Paris was signed on September 3, 1783, officially ending the American Revolution and granting independence to the United States of America. Perhaps more importantly for the settlers in Kentucky, the treaty brought an end to the steady stream of English guns and gunpowder to the Indians that had relentlessly attacked Kentucky during the war.

The American Revolution was winding down in the second half of 1782, with peace negotiations being conducted in earnest in Europe. But those talks appeared to have little impact on the actions of the main antagonists, as both sides were preparing invasions to punish their adversary.

Although Lord Charles Cornwallis surrendered to General George Washington at Yorktown in October 1781 and peace talks began in Europe soon thereafter, the brutal warfare in the Ohio Country and Kentucky continued unabated. Little did talks taking place in comfortable parlors thousands of miles away affect the Indians and Kentuckians, they were dealing with a daily dose of life and death affairs on the frontier.

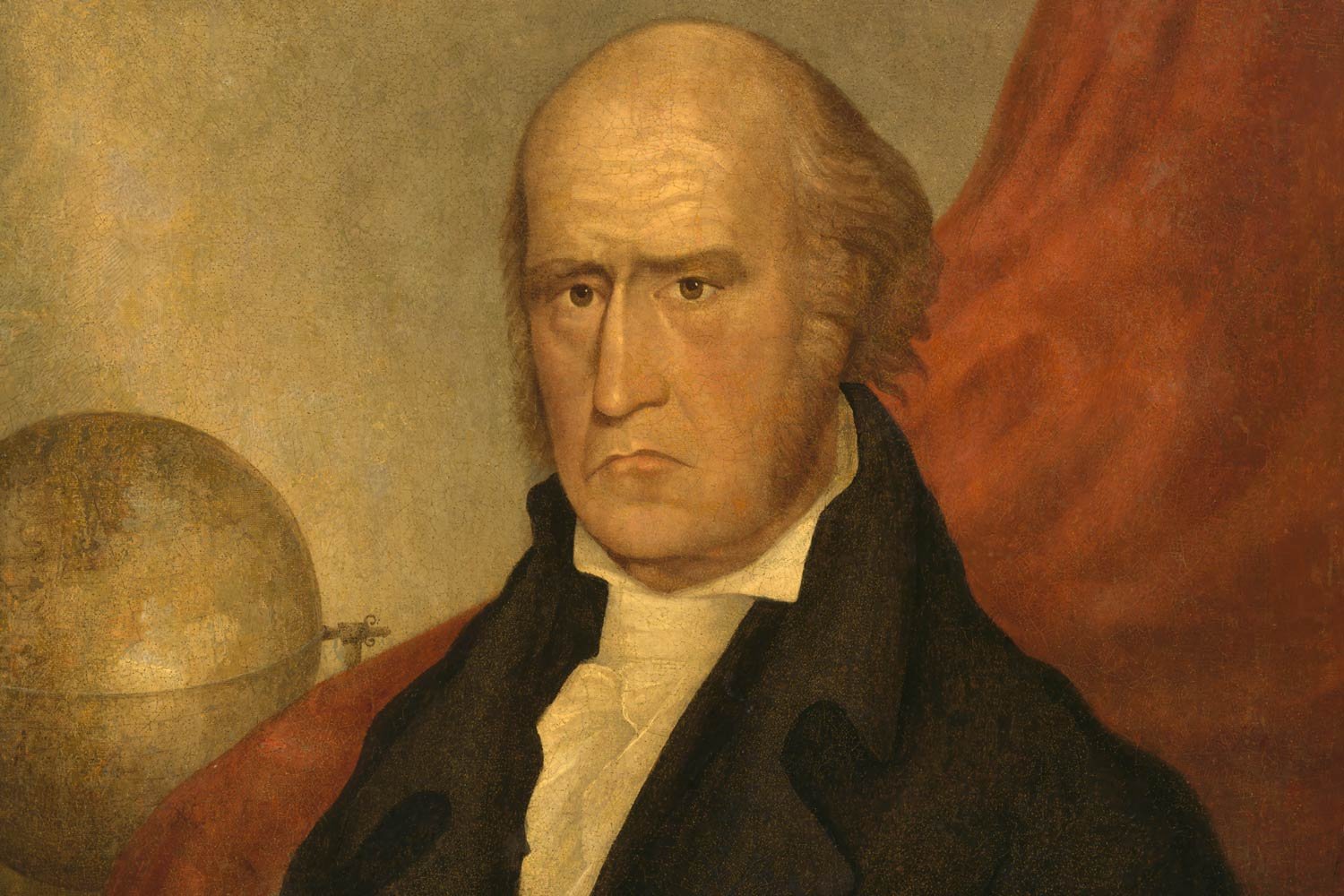

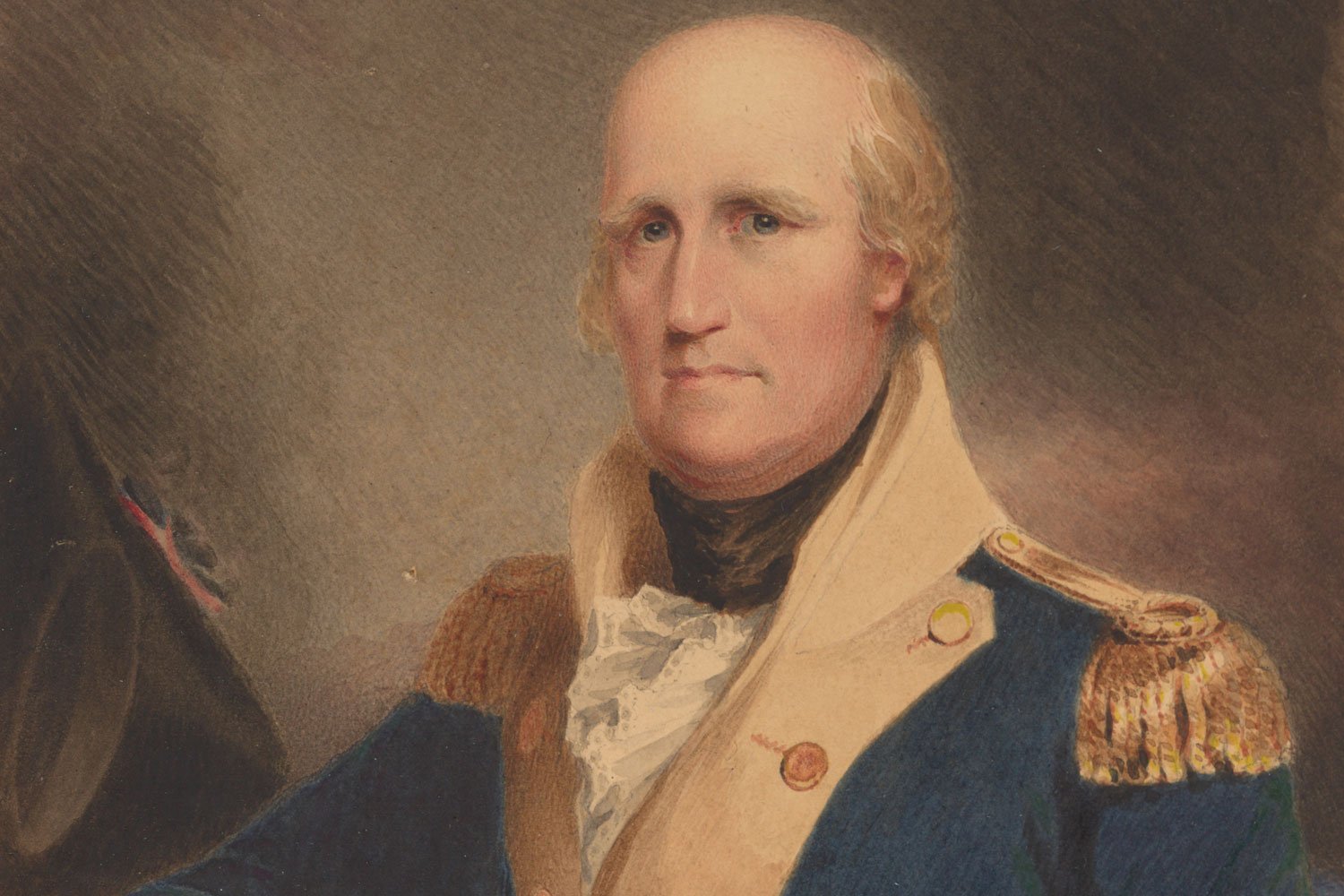

George Rogers Clark returned to Kentucky in February 1781 with visions of finally capturing the northern British bastion of Fort Detroit. However, although armed with a mandate from the Virginia legislature to raise an army and move on Detroit, very few Virginians were interested in participating in a campaign north of the Ohio when the British were in their backyard in the Tidewater region.

Kentucky had suffered greatly from Shawnee raids in June 1780 and Colonel George Rogers Clark decided it was time to take the fight into their homeland. His invasion across the Ohio would lead to the largest battle west of the Appalachians during the American Revolution.

With the capture of Fort Sackville, Kaskaskia, and Cahokia, Lieutenant Colonel George Rogers Clark had gained control of the southwestern portion of the Province of Quebec, better known as the Illinois Country, for the United States. Clark was at the height of his popularity, but the ambitious twenty-six year old wanted more and turned his attention to the crown jewel of British possessions in that part of the world, Fort Detroit.

Lieutenant Colonel George Rogers Clark and his band of 120 determined men arrived on the outskirts of Fort Sackville in the fading sunlight on February 23, 1779, undetected by the British garrison. They were tired and hungry, filthy and unshaven; they had not eaten for four days. After a two hundred mile trek across the flooded fields of what is now eastern Illinois, with their goal before them, Clark prepared to attack.

Following the British retaking of Fort Sackville on December 17, 1778, Lieutenant Colonel George Rogers Clark’s plan to conquer the Illinois Country for the United States was in peril. Without this strategic location in American control, his invasion of the southwestern portion of the Province of Quebec would be for naught, and continued incursions into Kentucky by Britain’s Indian allies would continue unabated.

The capture of Kaskaskia and Cahokia by Colonel George Rogers Clark had been surprisingly easy, with no bloodshed whatsoever. Not one to rest on his laurels, Clark immediately began to formulate a plan to crack a potentially tougher nut located about 180 miles to the east, the British post of Fort Sackville.

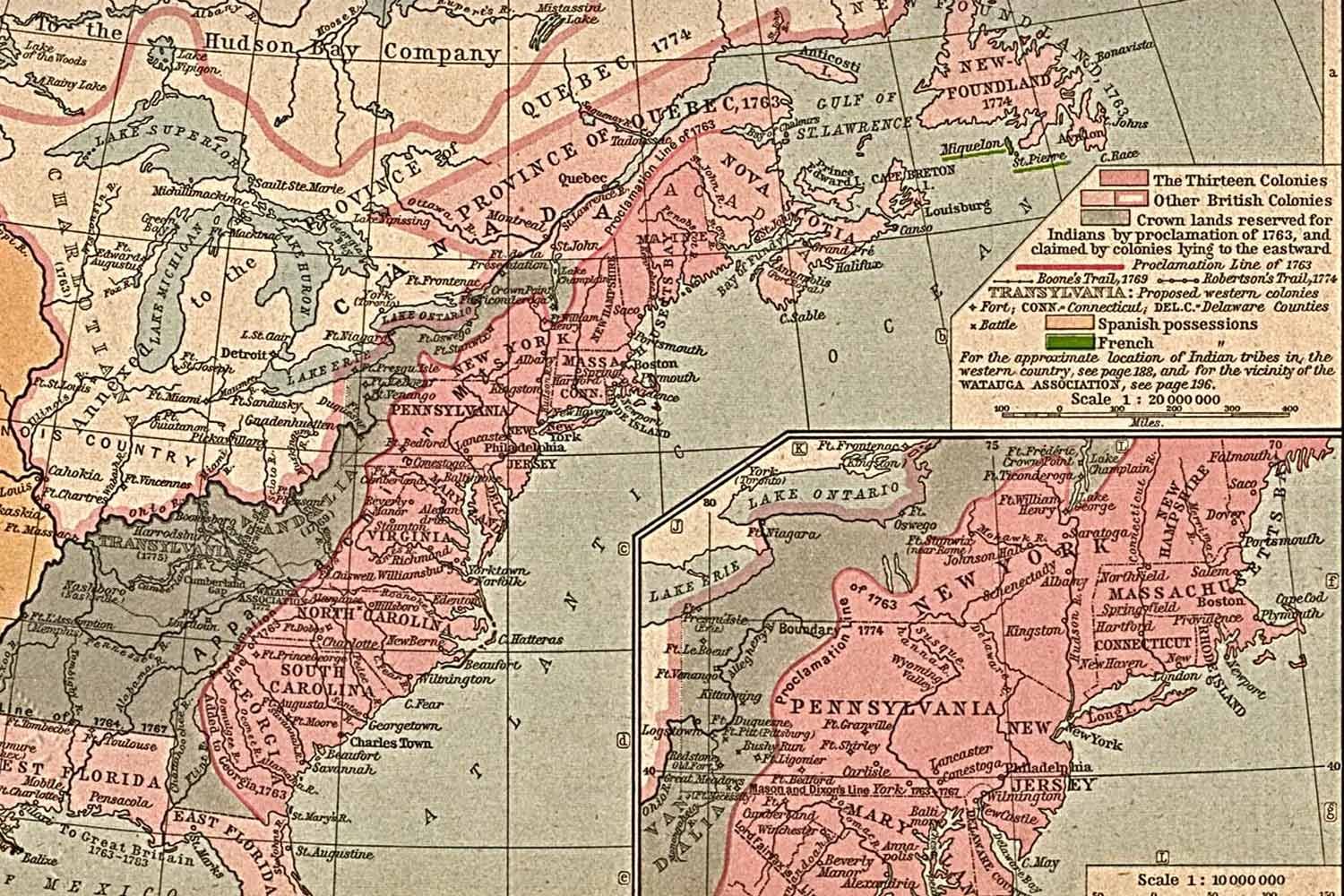

As the American Revolution continued in the east, the British removed all regular troops from their western outposts to assist in the more active theater. Naturally, that exposed a weakness in their defense, one that the intrepid George Rogers Clark would soon exploit with an invasion of the southwestern region of the Province of Quebec. The results of this conquest would be felt several years later when this land captured by Clark was granted to the United States by the Treaty of Paris.

Soon after the Battles of Lexington and Concord, the fledgling United Colonies invaded the British Province of Quebec. Despite the heroic efforts of men like General Richard Montgomery, Colonel Benedict Arnold, and Colonel Daniel Morgan, the 1775-76 invasion failed at the granite walls of Quebec City. A second, lesser known invasion, led by George Rogers Clark succeeded wonderfully a few years later, resulting in the largest capture of British territory during the American Revolution.

On the eve of the American Revolution, the lands west and south of the Appalachians were ripe for conquest. All that was needed to exploit this cauldron of trouble and take over this vast land was an intrepid man with a vision and a band of determined followers. That leader would emerge in the person of George Rogers Clark, and his extraordinary efforts would secure the Ohio River Valley for the United States.

By the end of 1765, peace was reached with the tribes who had participated in Pontiac’s rebellion, but all parties recognized this peace was tentative and temporary at best. The British colonist’s insatiable appetite for land and the Indians' need for huge swaths of unsettled wilderness for hunting were two incompatible desires.

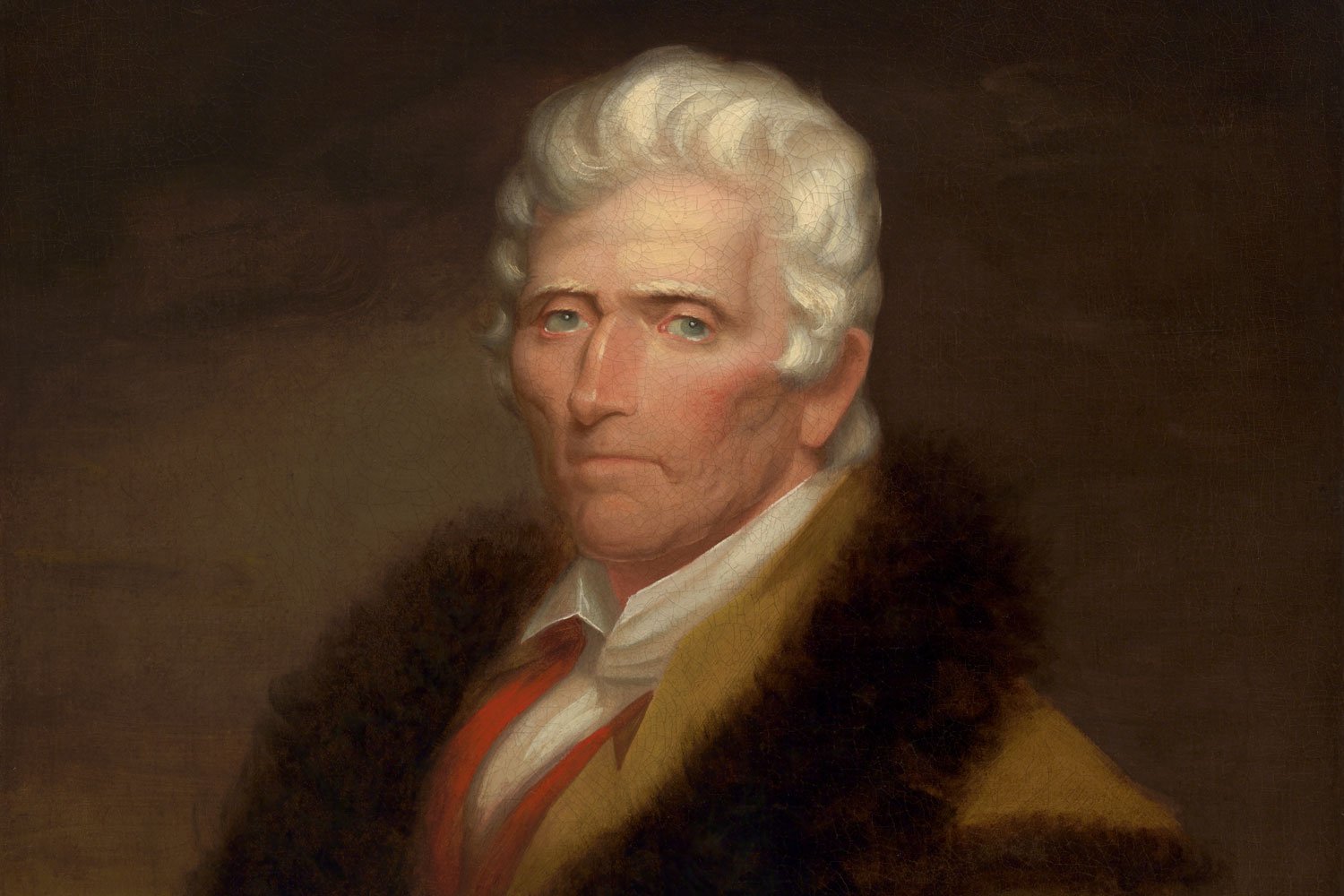

Soon after the American Revolution began in 1775, Daniel Boone joined the Virginia militia of Kentucky County (later Fayette County) and was named a captain due to his leadership ability and knowledge of the area. Over the next several years, Boone would participate in numerous engagements.

One of the greatest American explorers from our founding era was Daniel Boone. A legendary woodsman, Boone helped to make America’s dream of westward expansion in the late 1700s a reality.

The Wilderness Road, running from northeast Tennessee through the Cumberland Gap, was the main thoroughfare for Americans heading west into the new promised land of Kentucky from 1775 to about 1820. The pathway, blazed by Daniel Boone, was our nation’s first migration highway, but the trip was not for the faint of heart.

Americans have always had a yearning to move west and discover new lands. Along the way, our ancestors had to overcome many daunting natural barriers, the first of which was the Appalachian Mountains. The Wilderness Road through the Cumberland Gap was our nation’s first pathway through this formidable range.

With British fortune in the American Revolution at low tide in 1779, King Carlos III of Spain and his chief minister Jose Monino, Count of Floridablanca, decided the time was right for Spain to enter the war. But, for strategic reasons, they did not do so as a formal ally of the United States, but rather as one of France, their neighbor and cousin. As time would tell, Spain’s decision was instrumental in securing American independence.