Lord Dunmore’s War

In the fall of 1768, the British signed the Treaty of Hard Labour with the Cherokee and the Treaty of Fort Stanwix with the Iroquois, relinquishing parts of present-day West Virginia and Kentucky to the British. Although they provided a brief respite from the violence, they were not permanent solutions. In September 1773, Daniel Boone led fifty settlers, including his entire family, into Kentucky. The group was ambushed by Shawnee warriors near the Cumberland Gap and several men, including Boone’s son James, were killed and badly mutilated. Colonists in Virginia demanded action and, in 1774, Lord Dunmore, Virginia’s Royal Governor, launched two expeditions to destroy Shawnee villages in the Ohio Country.

Tom Hand, creator and publisher of Americana Corner, discusses the issues that led to Lord Dunmore’s War, and why it still matters today.

Images courtesy of Yale University, The New York Public Library, University of Michigan Library, Library of Congress , The Metropolitan Museum of Art, National Galleries Scotland, Encyclopedia Virginia, Wikipedia.

By the end of 1765, peace was reached with the tribes who had participated in Pontiac’s rebellion, but all parties recognized this peace was tentative and temporary at best. The British colonist’s insatiable appetite for land and the Indians' need for huge swaths of unsettled wilderness for hunting were two incompatible desires.

While Colonel John Bradstreet was relieving Fort Detroit, the southern expedition under Colonel Henry Bouquet was assembling at Carlisle before moving to Fort Pitt, the jumping off point for the campaign. Bouquet’s contingent arguably had the tougher assignment, that of penetrating deep into the heartland of the Delaware and Shawnee nations where every step through the trackless forest would be observed.

On June 24, 1763, the schooner sent out by Major Henry Gladwyn to inform British authorities of the situation at Fort Detroit finally made it back with much needed provisions, men, and ammunition, greatly strengthening the garrison’s resolve. Four weeks later, a second relief force of twenty-two ships, commanded by Captain James Dalzell with 280 men from the 55th and 80th Regiments, arrived at Fort Detroit on July 29.

With the forts around the Great Lakes taken by early June 1763, Pontiac’s Rebellion moved east towards the remaining British outposts along the frontier and the settlements just beyond. The following months would bring unprecedented bloodshed to American colonists, with long term consequences to colonial expansion plans.

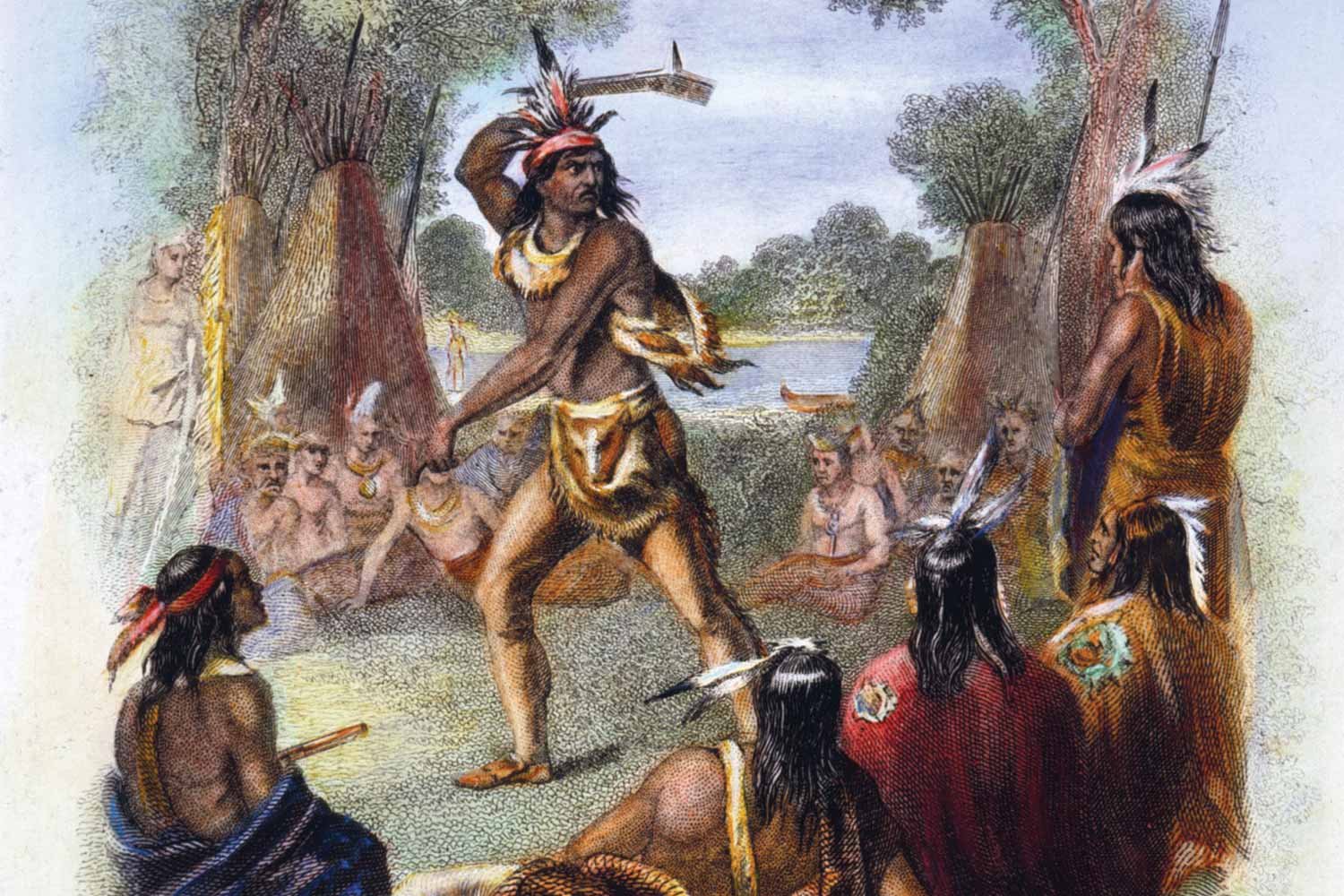

In mid-May 1763, Pontiac attacked Fort Detroit and initiated his grand plan to drive the British from the Great Lakes. Word soon spread to Indian villages across the region and other tribes soon followed suit. By the time Pontiac’s Rebellion ended in 1765, it would be the deadliest Indian uprising ever in North America.

All was set in May 1763 for an Indian uprising whose geographic extent and duration would surpass anything before or after in North America. The initial targets of Pontiac, the Indian mastermind behind the scheme, were nine British outposts, starting with Fort Detroit, the centerpiece of the region. Not coincidentally, this was the fort adjacent to Pontiac’s Ottawa village, with Potawatomi and Wyandot villages just across the Detroit River.

In the spring of 1763, following the conclusion of the French and Indian War, the Ohio Country and the Great Lakes region officially changed from French to British control. While markedly affecting the two European nations, the most significant impact fell on the Native Americans who lived in the region. Generally, these nations were unhappy with this transfer of power and worried that their way of life would be adversely affected. A charismatic Indian chieftain named Pontiac was determined to prevent this from happening.

Colonel Andrew Lewis and his 800 Virigina militiamen began setting up camp at Point Pleasant upon their arrival on October 6, 1774. Lewis selected this high ground where the Great Kanawha River empties into the Ohio because it provided “a most agreeable prospect” for an encampment. From this spot, where the Ohio River was 700-yards wide, Lewis felt he could observe any Indian activity and not be caught unawares.