Road to War, Part 6: James Madison, Father of the Constitution

In the summer of 1787, leaders from across the United States gathered in Philadelphia for the stated purpose of fixing flaws in the Articles of Confederation. But in the minds of nationalists like James Madison, fixing issues with the Articles was not the answer. What was needed was an entirely new form of government that could allow the fledgling nation to grow. This convention, known at the time as the Philadelphia or Federal Convention, was largely organized by Madison and Alexander Hamilton and the government created at that gathering bore Madison’s indelible stamp.

To give the gathering the credibility it needed to make significant changes to the government, Madison and Hamilton recognized the importance of having both Benjamin Franklin and George Washington in attendance, thus implying their tacit approval. Franklin, despite his age (he was 81) and constant issues with gout, happily attended telling his friend Benjamin Rush that the convention was “the most august and respectable assembly he was ever in in his life.” And, after much consideration and numerous letters and visits from Madison, Washington also agreed to attend. In a sign of the importance Madison placed on this convention, he assigned himself the task of taking detailed notes each day and refining them each night, leaving to posterity the most complete record of the convention.

In terms of the debate, the single most critical issue to be resolved was how representation in Congress would be determined, for with more representatives came more power. Madison believed that all representation should be based on population, not surprising given his home state of Virginia was the most populous state in the country. And to that end, when Edmund Randolph, Governor of Virginia, proposed his Virginia Plan, fifteen resolutions that were essentially Madison’s concept for the new government, the basis of the plan called for representation according to population in both chambers of Congress. But smaller states had little desire to join a national union that diminished their influence. As such, William Patterson of New Jersey put forth what has come to be known as the New Jersey Plan which called for equal representation in Congress for each state. Madison was at the center of this heated debate, without question the most intense of the entire convention, and his grasp of constitutional law and structure impressed all delegates. William Pierce of Georgia stated that of “the affairs of the United States, he (Madison) perhaps, had the most correct knowledge of any man in the Union.”

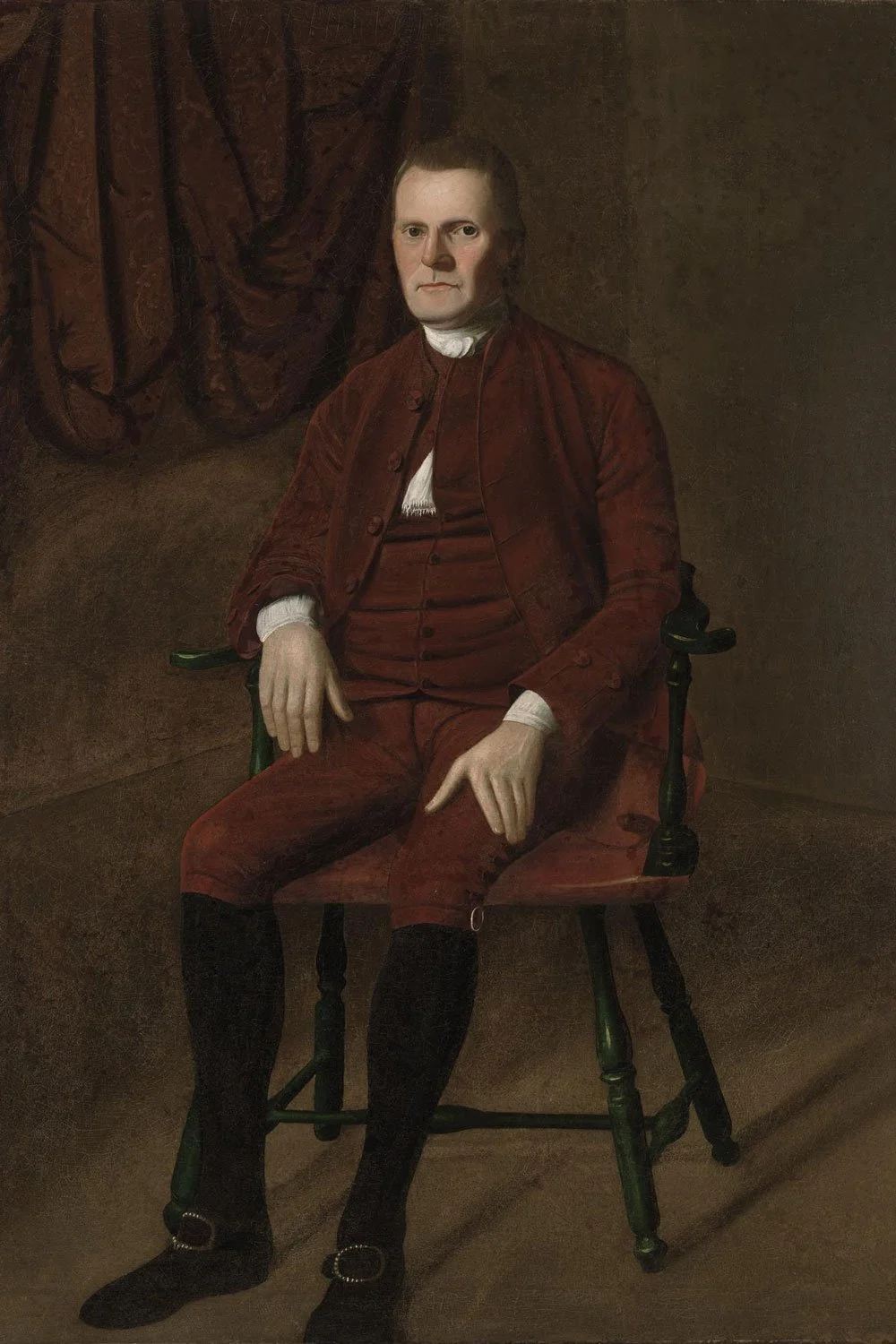

“Roger Sherman.” Yale University Art Gallery.

From these two conflicting plans, Roger Sherman crafted the Great or Connecticut Compromise which called for representation in the lower chamber (the House of Representatives) to be proportional according to population but for all states to have equal representation in the upper chamber (the Senate). Madison strongly opposed this compromise but ultimately Sherman’s proposal was adopted by a single vote. Despite this defeat and the disappointment felt by Madison and Washington, this compromise was a win for the nation as it prevented a premature end to the convention. As Madison later stated, “The threatening contest in the convention of 1787 did not, as you supposed, turn on the degree of power to be granted to the federal government, but on the rule by which the states should be represented and vote in government.”

And after the adoption of the Great Compromise, everything got easier; every issue was more easily overcome and other compromises were more easily found. Madison later wrote that, “from the day when every doubt of the right of the smaller states to an equal vote in the Senate was quieted, they…exceeded all others in zeal for granting power to the general government.” The smaller states recognized that a country unified behind a strong central government offered them a degree of protection that they could never achieve on their own. Ultimately, the Constitution was signed on September 17, 1787, by thirty-nine delegates representing twelve states (Rhode Island did not send a delegation). But that passage was only the first step in the adoption process. The next step, perhaps the most important, was getting the states to approve the Constitution at their separate ratifying conventions.

To help convince skeptical Americans of the merits of the new Constitution, Madison, Hamilton, and John Jay, in the fall of 1787, drafted a series of articles that has come to be known as The Federalist Papers. This series of eighty-five essays, arguably the greatest collection of writings ever on a federal constitutional government, laid out for the American public the argument for the adoption of the new constitution. Hamilton took the lead on these essays, writing fifty-one of them, while Madison drafted twenty-nine and Jay five (poor health limited Jay’s participation). While Madison’s contribution quantitatively was less than Hamilton’s, two of Madison’s essays are among the most prominent of the series. Federalist #10 argues that the sort of representative democracy proposed by the Constitution was the greatest safeguard against the excesses of partisanship and factionalism, while Federalist #51 explains the needs for a series of checks and balances between the three branches of government (legislative, executive, judicial) to hold those who govern in check, with Madison famously writing, “Ambition must be made to counteract ambition.”

Across the nation, eyes turned toward Virginia to see what direction that state would go as many prominent Virginians including Patrick Henry and George Mason were known to oppose the proposed Constitution. All understood that without Virginia’s approval, the Constitution could not be implemented. At the Virginia ratifying convention in June 1788, countering Henry’s great oratory with precise, logical arguments on the benefits of the Constitution, Madison carried the day, and the constitutionalists ultimately prevailed.

Thus, at every step in the constitutional process, James Madison took the lead. Madison organized the Constitutional convention, drafted the basic outline of the Constitution, recorded the proceedings for posterity, wrote many of the essays that swayed his fellow citizens, and was instrumental in convincing Virginians to adopt the new law of the land. No other Founding Father played such an outsized role in creating our nation’s Constitution.

And with the adoption of the Constitution, Madison seemed poised to help the Washington administration implement this new form of government, but that was not to be the case as Madison’s political views soon changed and he moved in a different direction.

Next week, we will discuss the great political transformation of James Madison. Until then, may your motto be “Ducit Amor Patriae,” love of country leads me.

In early May 1813, Commodore Isaac Chauncey loaded General Henry Dearborn’s army onto his waiting ships and sailed back across Lake Ontario for the second phase of Dearborn’s campaign, the capture of Fort George. Between the men stationed at Fort Niagara and Dearborn’s contingent, the American force consisted of roughly 4,000 men, with command of the army falling to 26-year-old Colonel Winfield Scott, destined to be one of the great military commanders in American history.