Road to War, Part 10: The Battle of Tippecanoe

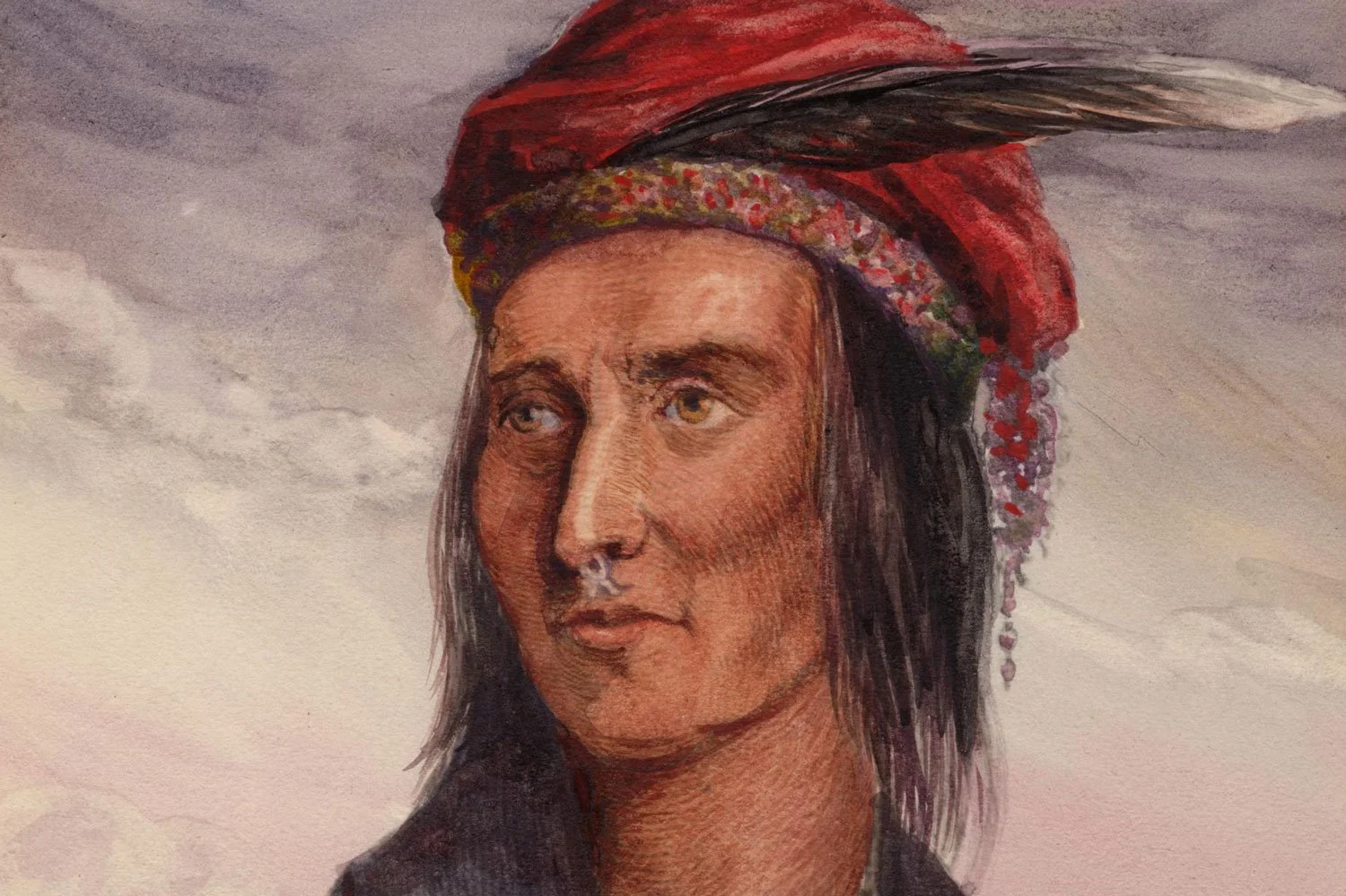

The last great battle between Indians in the old Northwest Territory and the forces of the United States, and one of the most consequential in our nation's early decades, was the Battle of Tippecanoe, fought on November 7, 1811, between Shawnee, Potawatomi, and Kickapoo warriors and American troops led by General William Henry Harrison, the Governor of the Indiana Territory. The Indians, unhappy with the continual encroachments on their land by American settlers, had gathered in Prophetstown to follow the teachings of Tenskwatawa, known as the Prophet.

Recognizing the need to strike before the situation got out of hand, Harrison planned an expedition up the Wabash River to erect a fort to intimidate and, hopefully, peacefully disperse the Prophet’s followers. Harrison requested that Secretary of War William Eustis order regular army troops be sent to assist in his effort so he would not have to rely simply on local militia. Eustis immediately dispatched the 4th Infantry Regiment, roughly 400 men under the command of Colonel John Boyd, from Fort Fayette to Vincennes. Boyd’s contingent arrived on September 19, bringing Harrison’s command to roughly 1,200 men, 800 militiamen from Indiana and Kentucky, including 200 of whom were mounted, and the soldiers of the 4th Infantry. A few days later, Harrison started his movement north to Prophetstown up the east side of the Wabash River with a long wagon train and cattle and hogs on the hoof to provide meat for the men.

Remembering the disasters of Harmar in 1790 and St. Clair in 1791, each evening Harrison had the camp enclosed with breastworks and posted a guard of over 100 men. Given the need to entrench each evening and the slow pace of the wagon train, the army covered about twelve miles a day. Harrison's force spent much of the month of October building Fort Harrison, roughly halfway between Vincennes and Prophetstown, to provide a base of operations closer to their destination. Near the end of October, Harrison resumed his movement north, crossing over to the west side of the Wabash which was more of an open prairie and less susceptible to ambush. Naturally, as the Americans approached, the Prophet and his followers grew alarmed and sent emissaries to Harrison asking his intention. Harrison responded that he was on a peace mission and simply hoped the Indians would disperse.

“William Henry Harrison.” National Portrait Gallery, Smithsonian Institution.

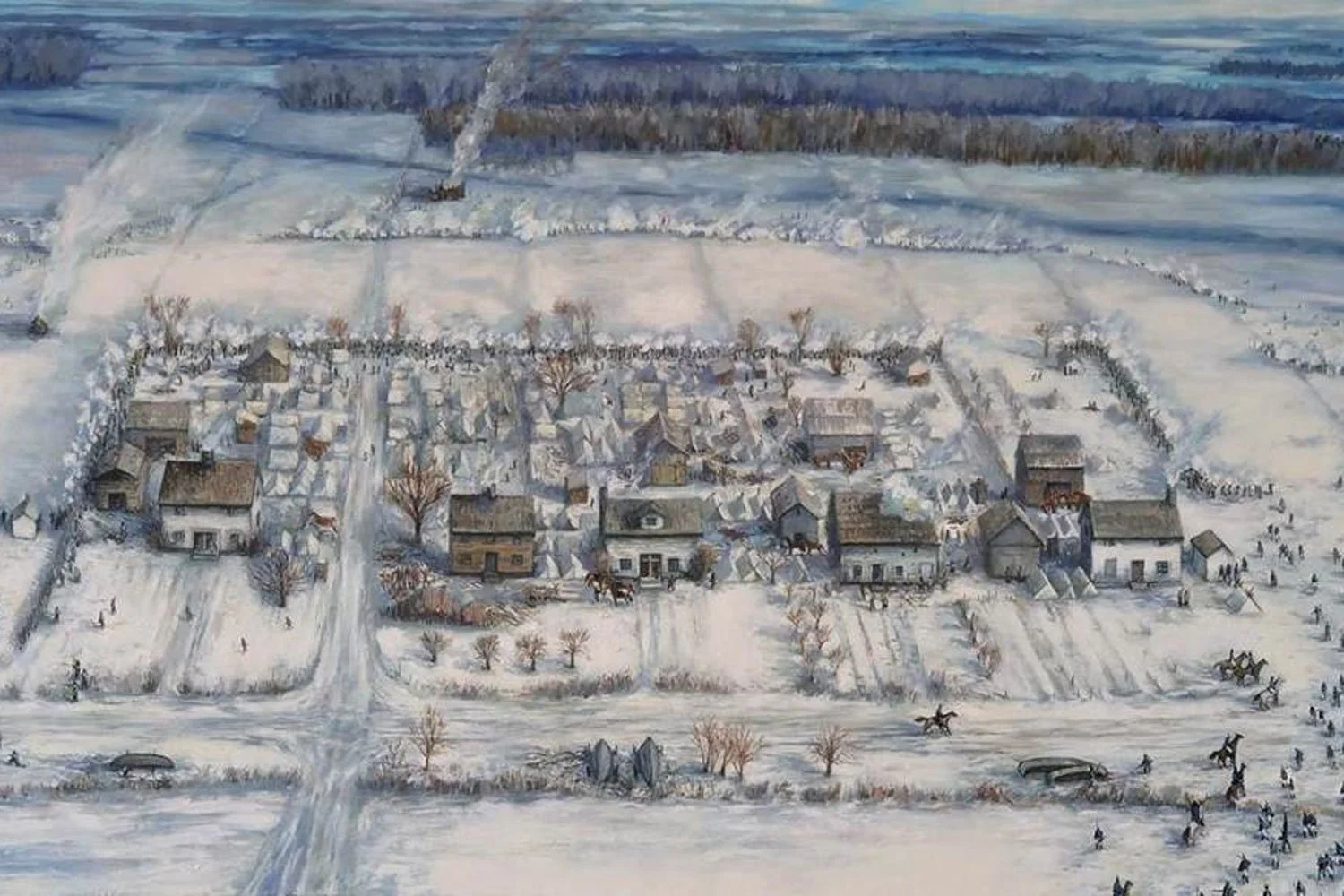

The Americans arrived outside Prophetstown the afternoon of November 6, five miles north of today's West Lafayette, IN, and set up a triangular shaped ten-acre camp. Most of Harrison's leading officers including Colonel Boyd and Colonel Joseph Daveiss, famous for charging Aaron Burr with treason, advised an immediate attack, worried that the Indians would take the initiative and strike that night. But Harrison was under strict orders from Secretary Eustis to maintain peace if possible and not initiate an attack. Harrison was also cautious because he estimated there were roughly 600 warriors in camp and, during that era, it was generally believed that Euro-American type armies, when engaged with Indians in their woodland domains, must outnumber Indians two to one to be successful. And between garrisoning Fort Harrison and losses due to desertion and sickness, the American army had dwindled to 950 men. Due to a lack of wood, the camp was not fortified with breastworks, for which Harrison was later criticized, but the troops were ordered to sleep with their bayonets fixed and cartridge boxes ready.

With Tecumseh away, the responsibility for dealing with the American army fell on Tenskwatawa. Although Tecumseh had stressed that a battle was to be avoided at all costs until his return, the Prophet felt he must do something. Accordingly, knowing that his followers believed him to be possessed of supernatural powers, Tenskwatawa chanted mystical words over the warriors that he pronounced would render them impervious to American bullets. Thus armed, the Indian warriors crept close to the American camp and attacked shortly before dawn on November 7. Despite the precautions taken by Harrison, the speed of the Indian attack was extraordinary, and a few warriors were in the camp and amongst the tents before the Americans could respond.

But Harrison kept his cool and immediately brought reinforcements to the endangered northwest perimeter of the camp and quickly stabilized his lines. The Indians soon made a second rush, this time on the American right, or northeast corner of the camp, and it too was driven back. Finally, a group of Winnebago warriors pressed an aggressive attack against the southern perimeter of the camp, but with Harrison moving reinforcements to the threatened area, those lines held firm as well. As dawn broke, the Indians were still on the outside of the camp looking in and dismayed at the determined resistance of the Americans. Harrison then ordered a counterattack from both flanks, and the fury of the American charge was too much for the Indians who fled the field, only to be run down by the mounted dragoons. The determination of the American soldiers and General Harrison’s calmness under fire resulted in a great victory, but it was dearly bought for they lost 37 dead and another 151 wounded, 29 of whom would die in the next few weeks. It was always difficult to measure Indian losses because they carried off most of their dead, but it is estimated that they lost about the same.

The Prophet and his remaining followers headed north to Wild Cat Creek, roughly 20 miles away, while Harrison ordered Prophetstown and several thousand bushels of corn burned, thus destroying the Indian’s food supply for the coming winter. Two days later, the Americans began their march back to Vincennes and a hero’s welcome from the grateful citizens. Not surprisingly, General Harrison was widely lauded for his leadership with militia officers stating, “the cool undaunted bravery of the commander-in-chief contributed more than even the courage of the army to defeat the ferocious…enemy that assailed us.”

With the failure of Tenskwatawa’s medicine and prophecies, came the end of his influence. Tecumseh returned in the spring to find that the confederacy he had worked so hard to create had largely splintered apart. But within months, Tecumseh’s hopes would be revived as the United States declared war on Great Britain and drove British support into Tecumseh’s waiting arms.

Next week, we will discuss the American plan for the War of 1812. Until then, may your motto be “Ducit Amor Patriae,” love of country leads me.

On September 12, 1813, General William Henry Harrison received word of Captain Oliver Hazard Perry's great victory on Lake Erie two days before. Recognizing that the Navy had done their part and cleared the lake of British warships, Harrison knew the time had finally come for the invasion of Upper Canada, and the General immediately put the wheels in motion to strike the British while he held the advantage.