War of 1812, Part 5: We Have Met the Enemy

The key to controlling Upper Canada in the War of 1812 was gaining naval mastery of the Great Lakes, especially Lakes Erie and Ontario. Given the lack of adequate roads in that area, neither side could hope to sustain an army of any size in the field without the ability to deliver supplies and reinforcements via these lakes. As 1813 opened, the British were in firm control of both and, despite the clamor of the Madison administration and Americans living west of the Appalachians to invade Canada, General William Henry Harrison, commander of the western army, was painfully aware that he must wait for a situational change on Lake Erie before beginning his advance.

To that end, in February 1813, Secretary of the Navy William Jones appointed Lieutenant Oliver Hazard Perry to take command of the American fleet on the lake. Perry was twenty-seven years old at the time but had already been serving in the United States Navy for twelve years, joining as a midshipman at age fifteen and serving under Commodore Edward Preble at Tripoli in the Barbary War. Perry was currently the commander of a flotilla of gunboats in Newport, Rhode Island, but chafing at the inactivity of his current post and anxious to get into the war. Perry jumped at the opportunity and reported to Sackett’s Harbor and Commodore Isaac Chauncey, commander of naval forces on Lakes Erie and Ontario. Chauncey ordered Perry to proceed to Presque Isle, today’s Erie, Pennsylvania, and there oversee the completion of six warships, two brigs, a schooner, and three gunboats that were already on the stocks. Perry, who had recently been promoted to Captain, was then to combine these vessels with five other warships at the Black Rock Naval Yard on the Niagara River and destroy the British fleet then controlling Lake Erie. Although Presque Isle was virtually undefended and the British were aware that the Americans were building warships there to take control of the lake, Sir George Prevost, Governor-General of Canada, inexplicably failed to attack the naval yard and destroy the ships. By May 24, all the vessels were completed and now only awaited the arrival of the ships from Black Rock before heading out to open water to confront the British fleet.

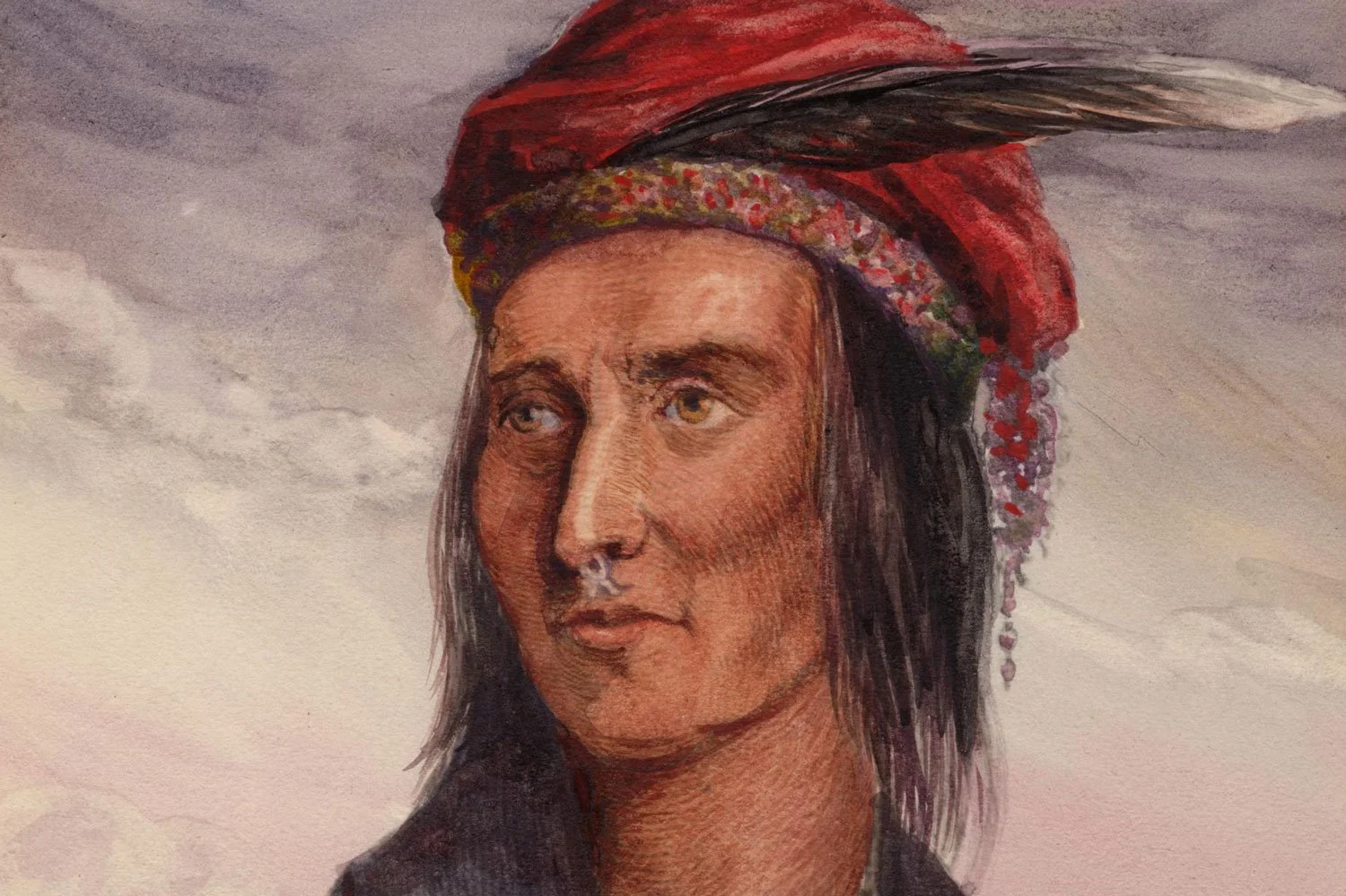

“Commodore Oliver Hazard Perry.” Toledo Museum of Art.

Providentially, at about that same time, the lone American victory on the Niagara front in 1813 took place, a successful assault on British controlled Fort George at the mouth of the Niagara River. This attack was carried out by General Henry Dearborn and Captain Perry, who briefly left Presque Isle to manage the flotilla carrying Dearborn’s army and its landing on Canadian soil. Dearborn’s success at Fort George forced the British to evacuate Fort Erie, across the Niagara River from Buffalo at the eastern end of Lake Erie and under whose guns all ships must pass to gain entry to the lake. With the threat at Fort Erie removed, Perry was able to sail the five American warships from Black Rock to Presque Isle in July and, after spending a month manning the vessels, Perry took his fleet in search of the British.

Meanwhile, the British had been busy assembling their own fleet below Fort Malden on the Detroit River. The commander was Captain Robert H. Barclay, thirty-two years of age, who had served under Admiral Horatio Nelson at the Battle of Trafalgar. Barclay’s fleet consisted of six ships, the largest which were the Detroit, 19 guns, and the Queen Charlotte, 17 guns. In comparison, Perry’s fleet consisted of nine warships, including two 20-gun brigs, the Lawrence, which Perry named his flagship, and the Niagara, which Perry assigned to Captain Jesse Elliott. Importantly, the tonnage that could be fired at close range by the Americans was almost double that of the British.

Just after dawn on September 10, Perry’s lookouts spied the British fleet in line of battle, roughly five miles away. At 11:45 a. m., the British long guns on the Detroit opened the engagement and Perry gave the order to close with the enemy. For a reason never fully explained, Captain Elliott on the Niagara disregarded Perry’s order and remained at long range, essentially out of the fight. Seeing the Niagara was holding back, Barclay focused British fire on Perry’s flagship the Lawrence and, for two long hours, the Lawrence fought the Detroit and the Queen Charlotte by itself. The Lawrence received terrible punishment, suffering eighty-three casualties out of a crew of 103, including all the officers either killed or wounded, except for Perry, who seemed to live a charmed life. Recognizing the Lawrence was in peril and assuming Perry was dead, Captain Elliott finally sailed the Niagara towards the fight. Seeing the Niagara, fresh and unharmed, entering the battle and knowing that the Lawrence must soon strike its colors, Perry made an incredibly bold decision. He ordered a boat lowered over the side and had a small crew row Perry to the approaching Niagara, attempting to transfer his flag to another ship in the midst of battle, an audacious move almost unheard of in naval warfare.

Captain Barclay, shocked but recognizing what Perry was up to, brought all his guns to bear on Perry’s rowboat, and soon the small crew was drenched from the round shot splashing around the boat; but Divine Providence must still have been watching over Perry as again he emerged unscathed from the ordeal. Upon reaching the Niagara, Perry took over command from Captain Elliott and boldly sailed the Niagara into the fray. Perry smashed through the British line, taking on five ships and firing broad sides to the right and left. Perry then brought the ship about and did the same thing one more time. Inspired by Perry’s heroic efforts, the other American ships that were still able to fight rejoined the battle. By now, Captain Barclay was wounded and his ships badly damaged by the superior weight of the American guns. And what had seemed to be a certain victory for the British turned into an inglorious defeat within fifteen minutes of Perry’s breakthrough of the British line. One after another, all British ships struck their colors and Perry returned to the Lawrence to receive the surrender of the British captains.

Then, taking a scrap of paper and pencil from his pocket, Perry sent a note for the ages to General Harrison, stating, “We have met the enemy and they are ours; two ships, two brigs, one schooner, and one sloop. Yours with great esteem and respect. O. H. Perry.”

Next week, we will discuss the Battle of the Thames. Until then, may your motto be “Ducit Amor Patriae,” love of country leads me.

Hello America!

Subscribe to receive weekly complimentary articles and videos delivered straight to your inbox.

The key to controlling Upper Canada in the War of 1812 was gaining naval mastery of the Great Lakes, especially Lakes Erie and Ontario. Given the lack of adequate roads in that area, neither side could hope to sustain an army of any size in the field without the ability to deliver supplies and reinforcements via these lakes. As 1813 opened, the British were in firm control of both and, despite the clamor of the Madison administration and Americans living west of the Appalachians to invade Canada, General William Henry Harrison, commander of the western army, was painfully aware that he must wait for a situational change on Lake Erie before beginning his advance.