War of 1812, Part 7: Disaster at Queenston Heights

The center thrust of the three-prong American advance into Canada was along the Niagara River frontier. This thirty-five-mile stretch was the most contested piece of real estate during the War of 1812 and would change hands several times over the course of the war. Secretary of War William Eustis entrusted the command of this sector to Stephen van Rensselaer, among the bluest of the blue bloods, a fifth generation landowner in upstate New York, descended from one of the earliest American patroons whose massive estate was on land granted to the family by the Dutch government when the area was the Dutch colony of New Netherlands. Not surprisingly given his wealth, van Rensselaer was a Federalist who had long served in the militia. When war came, President James Madison offered van Rensselaer a Major General’s commission and the command of the Niagara frontier, in part to keep van Rensselaer from running for Governor against Democratic-Republican George Tompkins. Despite his opposition to the war, van Rensselaer accepted the command, feeling he must put his country ahead of his personal feelings but fully aware of his lack of experience commanding large bodies of troops.

Although war had been declared on June 18, it took time for General van Rensselaer to assemble his army for the invasion of Canada across the Niagara River. But by early October, van Rensselaer’s army consisted of roughly 6,000 men, 2,000 regulars and militia under General Alexander Smyth at Buffalo, General William Wadsworth with 2,300 men at Lewiston, and 1,350 regulars at Fort Niagara. But right away there were command issues, as Smyth, a regular army officer, refused to take orders from van Rensselaer, who was his senior in rank but a militia officer. Consequently, when van Renssalaer announced his intention to invade below the falls, Smyth refused to participate in van Rensselaer’s plan as he thought the invasion should take place above the falls. Opposing the Americans on the Niagara front were 1,500 British soldiers, a combination of regulars and militia, and a smattering of Indians under the command of General Roger Hale Sheaffe and General Isaac Brock, the victor of Detroit. This small army was scattered across several outposts including Fort George at the mouth of the Niagara on Lake Ontario and Fort Erie at the head of the river on Lake Erie.

“John E. Wool. Brigadier-General.” New York Public Library.

Van Renssalaer established his headquarters at Lewiston, directly across the Niagara River from Queenston which sat atop bluffs two hundred feet above the river. At 3 a.m. on October 13, van Rensselaer put his plan in motion and sent 300 regulars and 300 militiamen under Lieutenant Colonel John Christie, commander of the 13th Infantry, across the river to take Queenston Heights, but the river at this point was full of swirling eddies and Christie's boat failed to make the landing. Consequently, the command devolved to Captain John E. Wool, a relatively new officer, and Colonel Solomon van Rensselaer, the General's nephew. Despite Wool’s inexperience, he immediately seized control of the situation and led his men from the riverbank to the plateau above where he and Colonel van Renssalaer organized the troops into line of battle. The British attacked and van Rensselaer, who was wounded five times, ordered a retreat to the riverbank to seek protection from the rocks below. Wool, despite being shot through both thighs, soon found another route to the top of the plateau, one on the steep side of the heights and unobserved by the British. Despite his wounds and the difficulty of the approach, Wool led his men to the summit and stormed the British position, driving the Redcoats from the field.

At this point, General Brock at Fort George, seven miles down the Niagara River, brought reinforcements to Queenston and personally led the charge up the hill. But Brock was shot from his horse, mortally wounded, as was his second in command Lieutenant Colonel McDonnell of the York militia and, with both commanders gone, the British soldiers retreated to the safety of their lines. American reinforcements soon arrived from across the river including General van Rensselaer, General William Wadsworth, and Lieutenant Colonel Winfield Scott.

As a group of Americans led by Scott dug in to secure their position, General van Rensselaer recrossed the river to encourage the 1,200 New York militiamen to hurry across and join the fight. Shockingly, the militiamen refused to leave American soil and no argument from General van Rensselaer could sway them. As van Rensselaer watched helplessly from across the river, he saw another long column of British soldiers led by General Sheaffe approaching from the direction of Fort George. At 4pm, Sheaffe began his assault of the American position, but the Americans held firm. Sheaffe then brought up his artillery and attacked both flanks and finally the American line finally broke, and the retreat became a rout. The Americans fled to the safety of the riverbank, hoping to be rowed to safety in the boats they expected to be waiting for them, but the river men refused to go back across the river and bring their countrymen to safety. Surrounded by an overwhelming force and with their backs against the river, Colonel Scott had no choice but to surrender. When the final tally was taken, the British lost about 130 men while Americans suffered 190 casualties and had another 900 Americans taken prisoner. Fortunately for the American cause, Scott would be returned to the Americans in a prisoner exchange the following month.

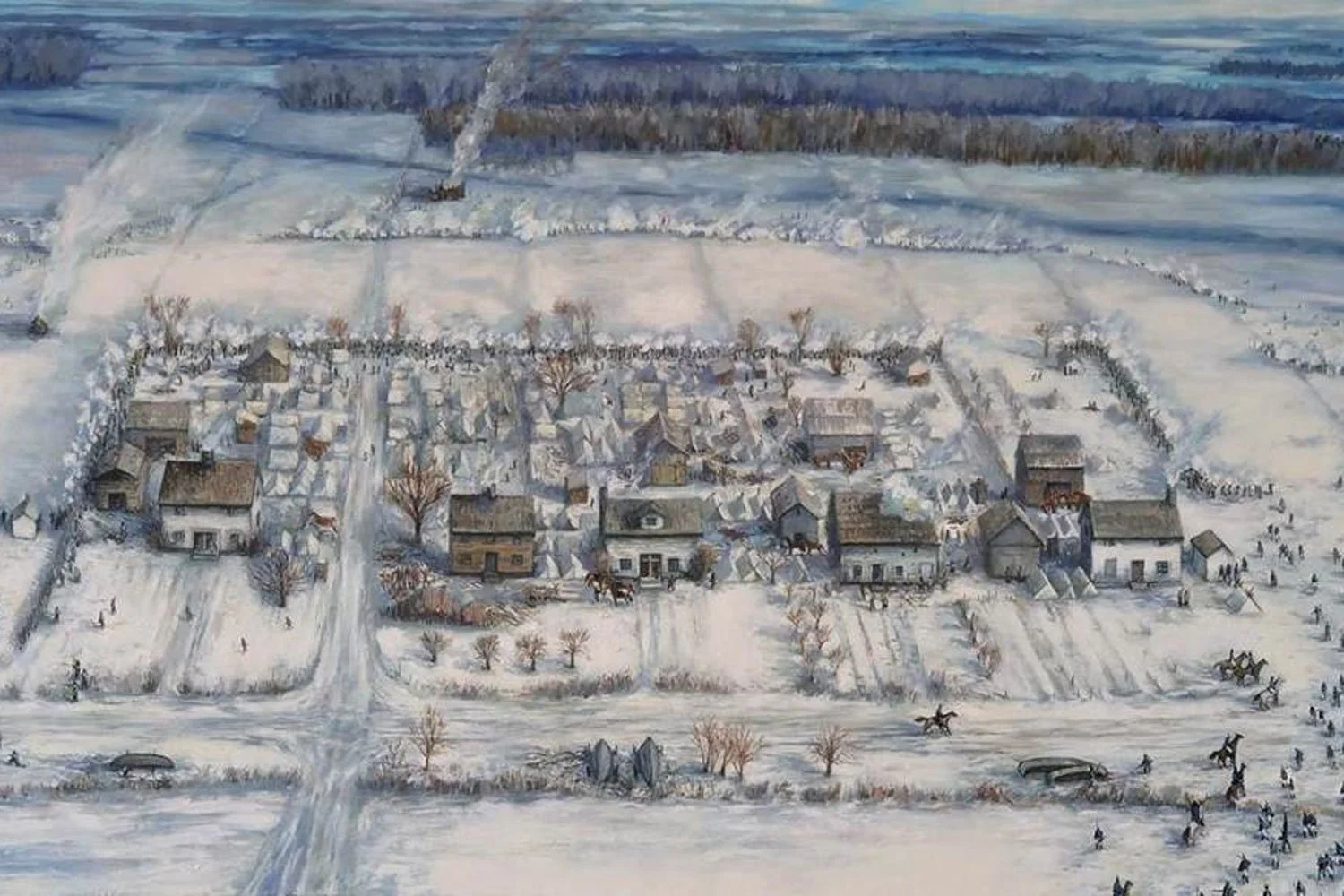

As for van Rensselaer, after his defeat at Queenston, the General resigned his commission and Smyth, the regular army officer who refused to support van Rensselaer’s plan, assumed command. Smyth immediately issued a call to arms and within a month raised a force of roughly 4,500 men. But Smyth was more a man of talk than of action and, after raising the force and planning two attacks on Canadian soil, failed to execute either attack. Frustrated with Smyth and the inactivity, many New York militiamen headed home, while Smyth resigned three months later and returned to Virginia where he was elected to Congress.

The rest of the army went into winter camp thus ending the land campaign of 1812. It had been a dismal performance thus far by the Americans between the surrender of Detroit, the embarrassing loss at Queenston Heights, and a complete lack of activity on the Montreal-Lake Champlain front. What was supposed to be a walk in the park according to Warhawks like Henry Clay, turned out to be anything but that. However, plans were made to reverse the situation the following year.

Next week, we will discuss the burning of York. Until then, may your motto be “Ducit Amor Patriae,” love of country leads me.

Hello America!

Subscribe to receive weekly complimentary articles and videos delivered straight to your inbox.

The center thrust of the three-prong American advance into Canada was along the Niagara River frontier. This thirty-five-mile stretch was the most contested piece of real estate during the War of 1812 and would change hands several times over the course of the war. Secretary of War William Eustis entrusted the command of this sector to Stephen van Rensselaer.