Road to War, Part 9: Tecumseh and the Prophet

Tecumseh’s War was the last great Indian war in the Northwest Territory and raged from 1811 to 1817. The cause of the conflict was Indian anger at the numerous land cessions made between Indian nations and the United States from 1803 to 1809. While this war overlapped with the War of 1812, the two conflicts were separate events with different goals for the participants. While the one was in part a struggle between Great Britain and the United States for the control of Upper Canada, Tecumseh’s War was the final effort by Indian nations in the Great Lakes region to stem the tide of American expansion into their native homelands. Significantly, Tecumseh’s War was the last time a European power would ever support Native Americans in a conflict. And because the only chance Indian nations had to stand up against American forces was if they were supplied with European weapons, Tecumseh’s War was the last time North American Indians had even a remote chance of victory.

“Anthony Wayne.” National Portrait Gallery, Smithsonian Institution.

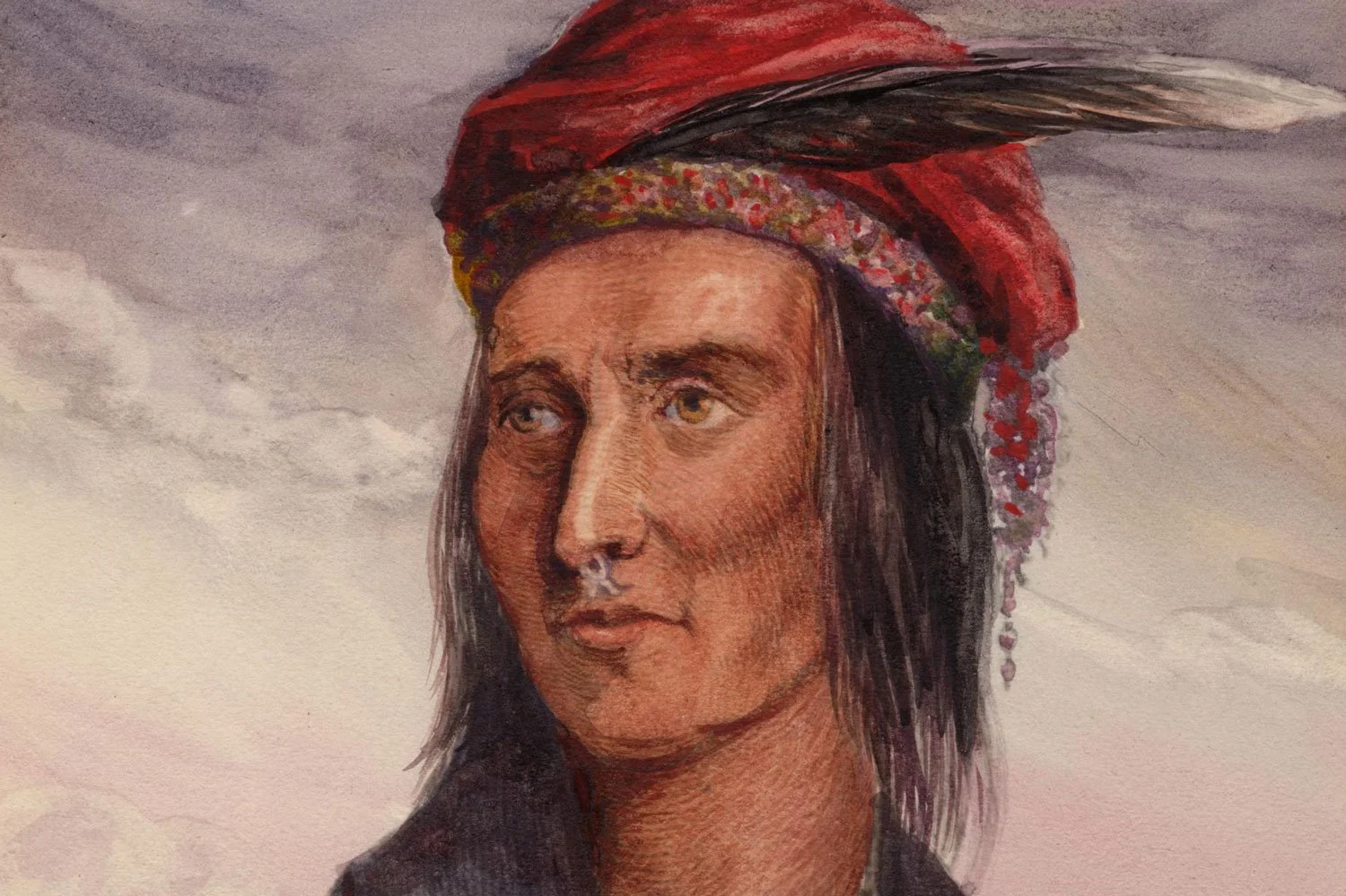

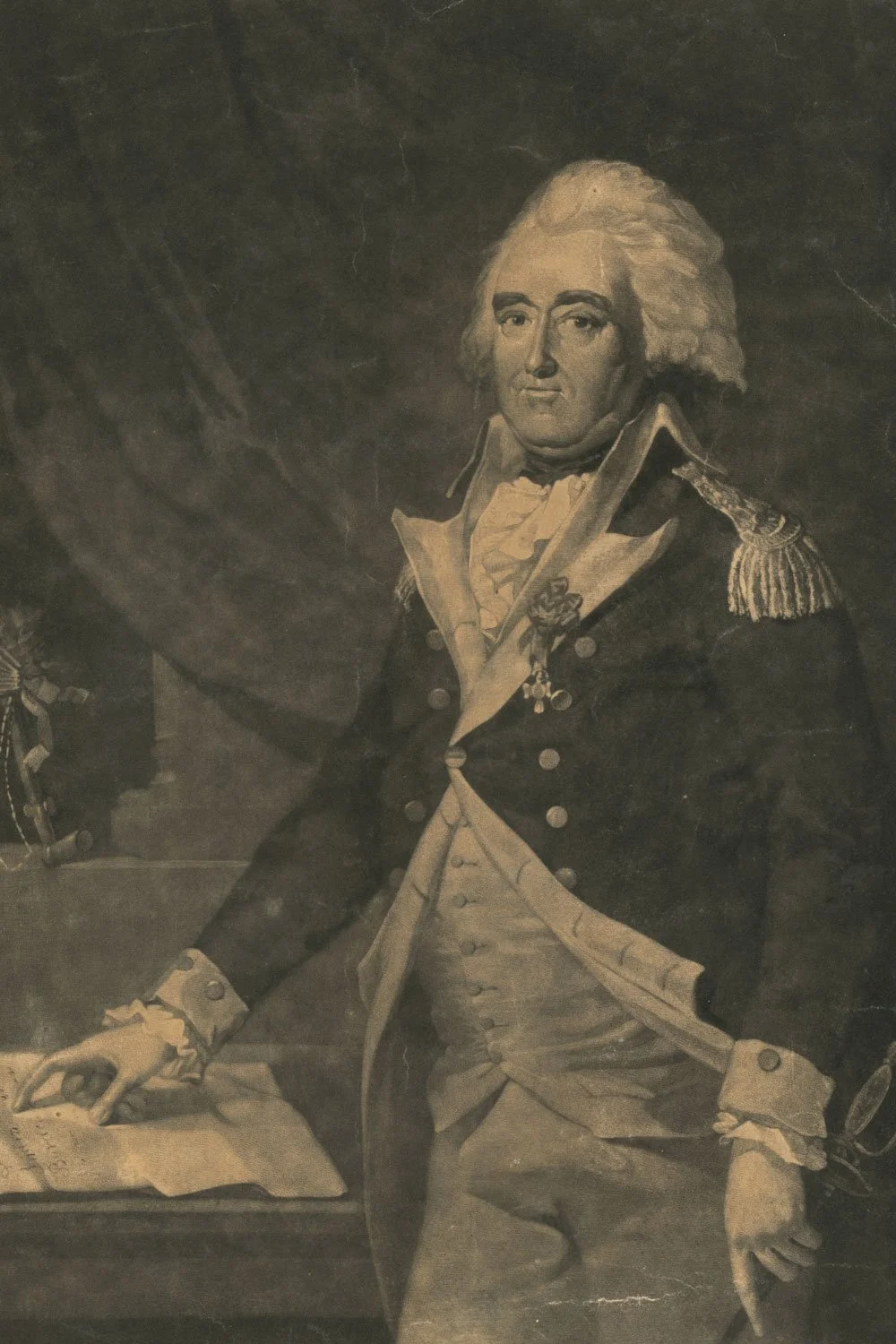

Tecumseh, whose name appropriately means Shooting Star, was a Shawnee born in 1768 in Old Piqua, part of the Ohio Country. Little is known of his early life except that he was orphaned at a young age and raised by older siblings and that even as a youth Tecumseh was notable for his bravery and aggressive spirit. In the spring of 1788, Tecumseh began accompanying warriors on raids into Kentucky and attacking flat boats descending the Ohio. In 1794, Tecumseh took part in the Battle of Fallen Timbers in which General Anthony Wayne and his Legion of the United States dealt a crushing blow to the Shawnee nation. Tecumseh’s unhappiness with both British and American authorities and the loss of what he considered his ancestral homeland caused Tecumseh to head further west to live the life of his ancestors, establishing a small village on the White River in east-central Indiana. By all accounts, Tecumseh was a formidable looking man and an exceptional warrior, and both allies and enemies were impressed with Tecumseh’s noble bearing and demeanor. British General Isaac Brock called Tecumseh “the Wellington of the Indians” and stated that “a more sagacious or more gallant warrior does not I believe exist.” And General William Henry Harrison, who would become Tecumseh’s greatest nemesis, commented that Tecumseh was “one of those uncommon geniuses, which sprang up occasionally to produce revolutions and overturn the established order of things.”

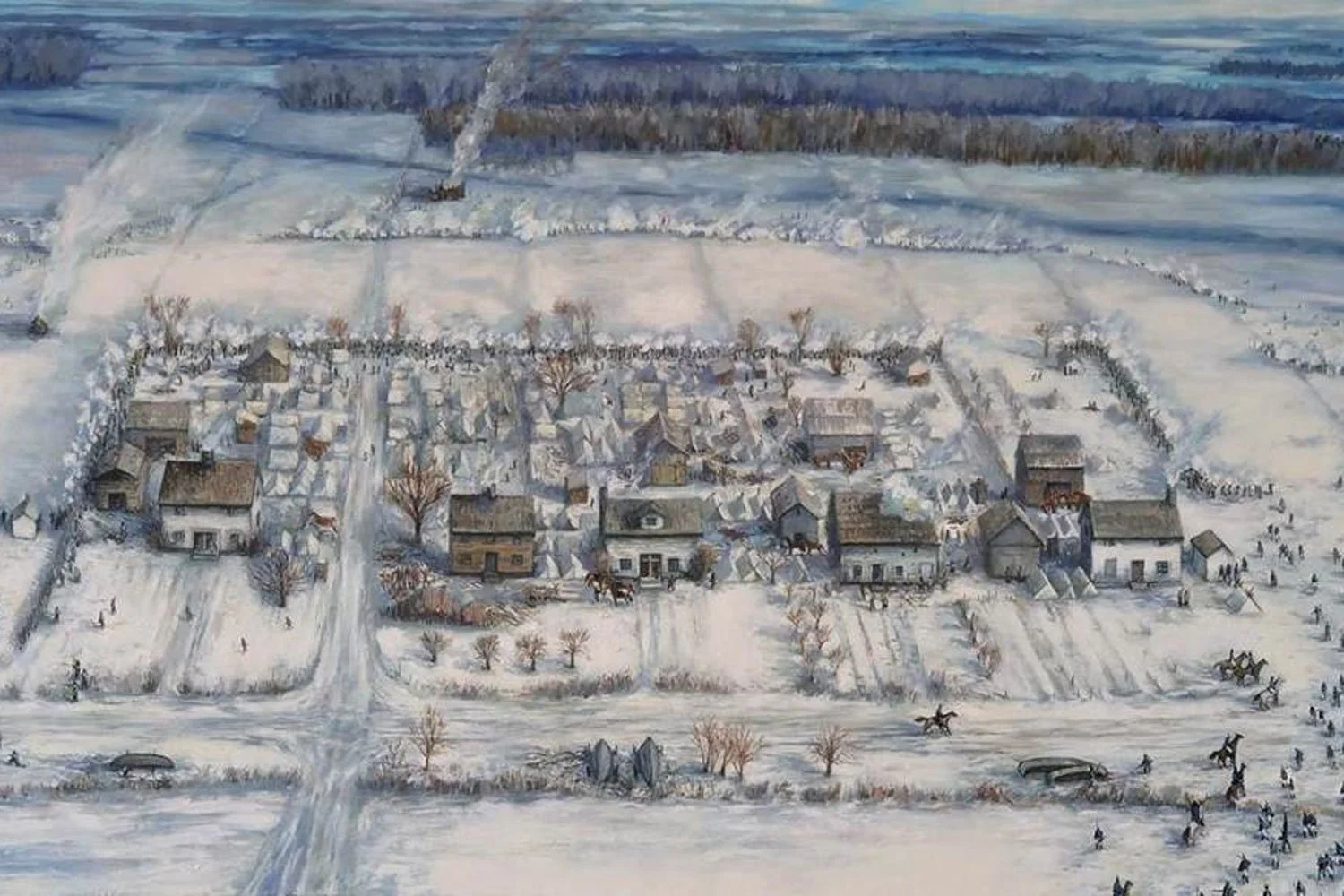

Despite Tecumseh’s prowess, he may have remained unknown to history were it not for his brother Tenskwatawa, better known to history as the Prophet, who rose to prominence in 1805 following a series of visions. The Prophet claimed the Great Spirit, or Master of Life, desired that the Shawnee return to their ancient ways and renounce white man's dress, drink, and customs, and forbidding Indian women to marry white men. The Prophet further urged Indians to discard domestic livestock and instead rely on hunting and traditional foods such as corn, beans, and squash, and especially to avoid alcohol, reminding his followers that this white man's poison only brought misery. The purer mode of life preached by the Prophet grew into a sort of religion that promised a reward for its adherents in the afterlife and gained followers as his message reached more and more Indian villages. By 1808, the Prophet, who had once been a drunkard and held in low regard by his fellow tribesmen, emerged as one of the most influential men in the region and established the village of Prophetstown at the confluence the Wabash and Tippecanoe rivers, roughly 150 miles north of the territorial capital of Vincennes.

Part of the reason why the Prophet’s message resonated so well with Indians in the Great Lakes region was their growing frustration over repeated land cession treaties between willing chiefs and the United States. This rapid expansion of federal land was the result of an aggressive expansionist policy of President Thomas Jefferson who came to power in 1801 and envisioned an “empire of liberty” stretching across the continent. While the 1803 Louisiana Purchase is the best-known manifestation of this policy, his actions in the Northwest Territory followed the same pattern. The President hoped to turn Indians into farmers, largely adopting the white man's agricultural way of life, or, failing that, push them further west across the Mississippi. Consequently, between 1803 and 1809, the President instructed General Harrison, the Governor of the Indiana Territory, and others to sign a series of fifteen land cession treaties with various tribes yielding over 70,000 square miles (44,000,000 acres) of Indian land to the United States. The last of these treaties was the Treaty of Fort Wayne and, although it ceded only 4,700 square miles, it proved to be the straw that broke the camel's back.

The third interested party in the Northwest Territory was the British whose province of Upper Canada bordered the northern shoreline of the Great Lakes. The British had been supportive of Indian nations in the region since acquiring Canada from the French in 1763 but had significantly reduced that support since the Jay Treaty in 1795. But as Great Britain and the United States drifted closer to war, especially after the Chesapeake-Leopard affair in 1807, the British began to rethink their Indian policy. Recognizing that if war broke out with the United States Indian assistance would be critical to British success in Upper Canada, the British walked a tightrope between maintaining ties to the Indian nations in the region and yet not guaranteeing their support in an Indian war with the United States. Consequently, when Tecumseh traveled to Fort Amherstburg in 1810 to seek guarantees of British support should war breakout, British officials were evasive.

In 1811, Indian raids became more frequent, and Harrison requested a meeting with Tecumseh to settle differences. Their strained talks yielded no results, but during the meeting Tecumseh informed Harrison that he would be away from Prophetstown until the following spring. Although Tecumseh did not state the reason for his absence, he was traveling south to recruit tribes for his confederacy in the Mississippi Territory, modern-day Mississippi and Alabama. Harrison, worried that an Indian war was in the immediate future and fully aware that Tecumseh’s absence would weaken the confederacy, soon put plans in motion to defuse this potential rebellion before it became a reality.

Next week, we will discuss the Battle of Tippecanoe. Until then, may your motto be “Ducit Amor Patriae,” love of country leads me.

The key to controlling Upper Canada in the War of 1812 was gaining naval mastery of the Great Lakes, especially Lakes Erie and Ontario. Given the lack of adequate roads in that area, neither side could hope to sustain an army of any size in the field without the ability to deliver supplies and reinforcements via these lakes. As 1813 opened, the British were in firm control of both and, despite the clamor of the Madison administration and Americans living west of the Appalachians to invade Canada, General William Henry Harrison, commander of the western army, was painfully aware that he must wait for a situational change on Lake Erie before beginning his advance.