Road to War, Part 8: The Fifty-Year War for the Old Northwest

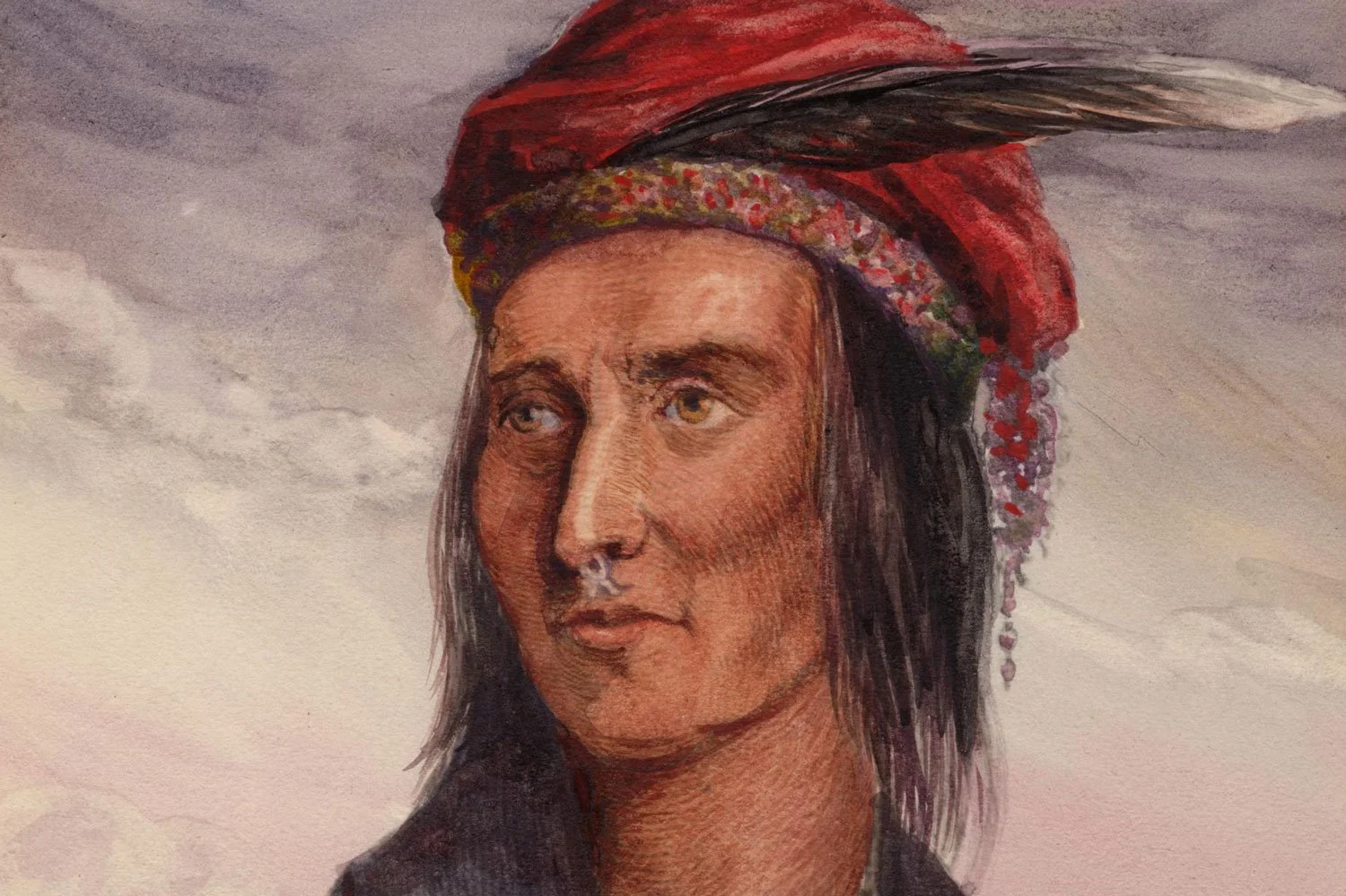

When James Madison was sworn in as President on March 4, 1809, his most pressing issue was dealing with British and French violations of American neutrality on the high seas. But he also had a rising issue in the west in the form of an Indian confederacy headed by the Shawnee chief Tecumseh and his younger brother, Tenskwatawa, better known to history as the Prophet. The focal point of this movement was the old Northwest Territory, the most fought over area in American history where white settlers and Native Americans vied for control in a virtually continuous conflict that lasted for more than fifty years before coming to an end in 1817.

The French were the first Europeans to reach this fertile land, but they were not interested in colonizing North America as much as exploiting the area’s abundant natural resources, especially the rich fur trade. Over the course of a century, the French created alliances with many tribes and supplied them with greatly desired European metal utensils and weapons in exchange for furs and, as a result, the French were welcomed by the Indians. But with the end of the French and Indian War in 1763, the British gained possession of all French lands in North America, including the Northwest Territory which was then part of Canada. Unfortunately, while the French traders blended into Indian culture, many of them taking Indian wives, the British very much considered themselves masters of the Indian nations and treated the natives as conquered people.

Despite the Royal Proclamation of 1763 which was intended to check colonial encroachments on Indian land and subsequent agreements between British authorities and Indian nations such as the 1768 Treaty of Fort Stanwix, Americans eyed this land for settlement and were not to be put off by decrees passed by Parliament. In 1769, Daniel Boone, following in the footsteps of Thomas Walker, passed through the Cumberland Gap and, in 1775, blazed the Wilderness Road into Kentucky. As more settlers poured into Kentucky and others floated down the Ohio River in search of land, Americans began to homestead on Indian land north of the Ohio and, quite naturally, met with violent resistance from the tribes then occupying the area.

In 1761, an Ottawa war chief named Pontiac began organizing a confederacy of a dozen Indian nations including Ottawa, Miami, and Shawnee across the southern crescent of the Great Lakes region, from Lake Michigan to the eastern end of Lake Erie to resist white settlement. Two years later, Pontiac initiated his war with an attack on Fort Detroit in May 1763. Pontiac's adherents captured and destroyed eight British forts and killed hundreds of settlers and soldiers until the British army finally regained control of the region in the fall of 1764 and secured the peace through several treaties including the Treaty of Niagara.

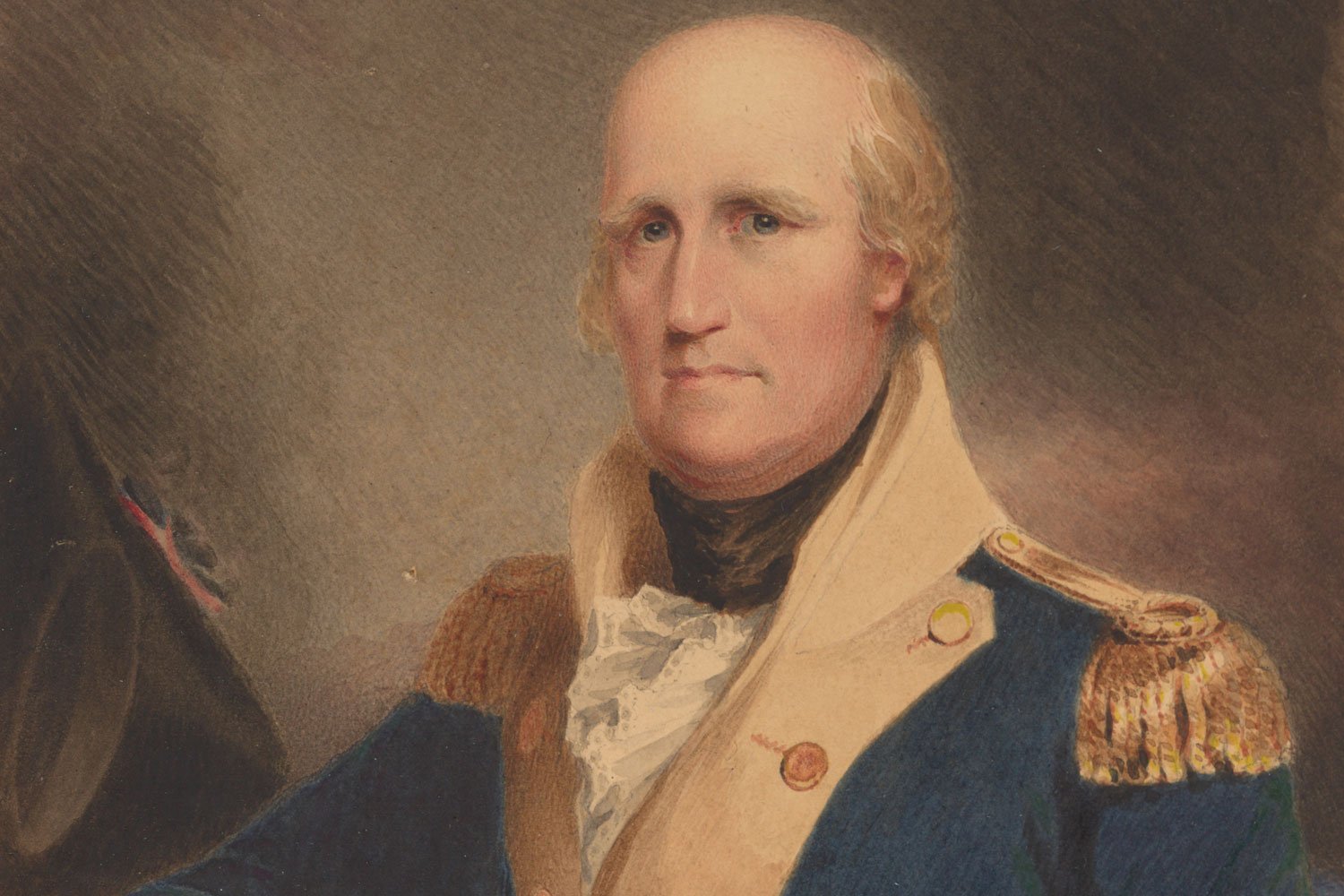

“George Rogers Clark.” National Portrait Gallery, Smithsonian Institution.

But in the complexity of the Indian world, treaties signed by one chief or one tribe were not necessarily honored or accepted by other chiefs or other tribes or even by other chiefs within the same tribe. As a result, Indian depredations on settlers both north of the Ohio and in Kentucky frequently occurred. Naturally, the settlers demanded protection, first by Royal authority and then, with the onset of the American Revolution, the responsibility shifted to the fledgling Confederation Congress. However, due to its limited resources, Congress was unable to assist in the West with the ongoing Indian wars and both protection and retribution fell to militia units formed in Kentucky by leaders such as George Rogers Clark, Daniel Boone, and John Todd.

With the successful conclusion of the war in 1783, the Indians in the northwest lost the support of the British. It was hoped that as a result peace would finally come to the area and for a while it did, but it proved to be a brief respite. That same year, a brilliant Mohawk chief named Joseph Brandt, formed the Northwestern Confederacy and gathered delegates from thirty-five Indian nations on the upper Sandusky River. Like Pontiac, Brandt’s goal was to unite Indian nations to resist encroachments on their ancestral lands and, by the mid-1780s, depredations by the Indians in this region began to rise.

With the establishment of the new Constitution in 1789, the federal government finally had the authority to raise and fund an army and President George Washington, who was committed to bringing the Indian atrocities in the Northwest Territory to an end, immediately put an army in motion. In 1790, Washington ordered General Josiah Harmar to take an army north from Fort Washington, today’s Cincinnati, on a punitive raid and destroy as many Miami and Shawnee towns as possible and, thereby, deter the Indians from future attacks. Instead, Harmar suffered a serious reverse by a coalition of warriors led by the Miami chief Little Turtle.

Embarrassed by the defeat, the President ordered Arthur St. Clair, the territorial Governor and a former General in the American Revolution, to take a second force north to put down the rebellion. But in 1791, St. Clair suffered the greatest loss ever inflicted on the United States Army by Native Americans in the Battle of the Wabash, better known as St. Clair’s Defeat. Finally, in 1794, General Anthony Wayne and his Legion of the United States dealt a crushing blow to a large native force led by Little Turtle and a Shawnee chief named Blue Jacket at the Battle of Fallen Timbers, near today’s Maumee, Ohio, destroying the Northwestern Confederacy. The following year General Wayne dictated the Treaty of Greenville to the confederacy, establishing the Greenville Treaty Line and and reserving the southeastern two-thirds of Ohio for the United States and the rest of the Northwest Territory for the Indians.

The Greenville Line was intended to be permanent but as was always the case with Indian treaties, nothing was permanent, and between 1803 and 1809 fifteen more land cession treaties were signed. Twelve of these agreements were initiated by William Henry Harrison, Governor of the Indiana Territory, who would soon be confronted by a coalition of Indians unhappy with the loss of their land.

Next week, we will discuss Tecumseh’s Confederacy. Until then, may your motto be “Ducit Amor Patriae,” love of country leads me.

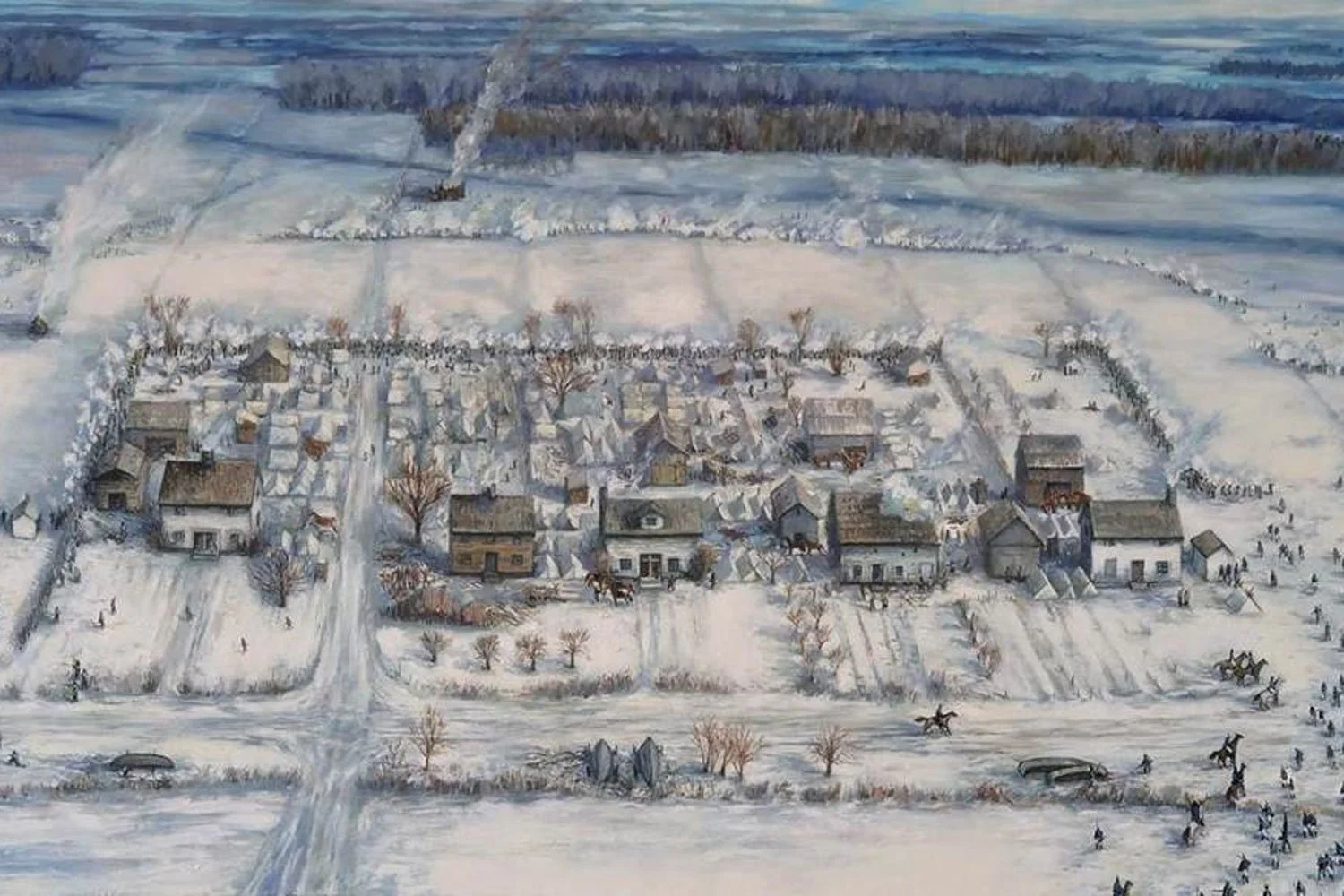

Following the American disaster at Frenchtown, General William Henry Harrison gathered another force to turn the tide in the West. On February 1, 1813, Harrison returned to the rapids of the Maumee with 1,800 Pennsylvania and Virginia militiamen and tasked Major Eleazer D. Wood of the Engineers, an early graduate of West Point, to construct Fort Meigs. Wood finished the fort by the end of the month, but unfortunately the enlistments of most of the men expired at the same time and Harrison was left with a formidable fort but a garrison of less than 500 soldiers.