War of 1812, Part 3: Debacle on the River Raisin

Following General William Hull’s ignominious surrender of Fort Detroit, the outlook for the United States in Upper Canada was bleak. The western army essentially had been eliminated with Hull’s surrender, and a new army had to be raised. But perhaps more importantly, a new commander had to be found, and that man would be William Henry Harrison, governor of the Indiana Territory and acclaimed in the West as the hero of Tippecanoe.

Harrison was born on February 9, 1773, on the family estate of Berkeley Plantation, twenty-five miles southeast of Richmond, the son of Benjamin Harrison V, a signer of the Declaration of Independence. Harrison was a smallish man at 5’8” and slightly built, but he had dreams of martial glory and at age eighteen obtained a commission in the 1st Infantry Regiment. In 1794, Lieutenant Harrison accompanied General Anthony Wayne as his aide-de-camp on Wayne’s campaign to destroy Little Turtle’s Northwestern Confederacy and participated in the climactic Battle of Fallen Timbers, where Harrison’s performance won many laurels. But with the destruction of the Confederacy came an end to opportunities for Harrison to advance his career and, despite being promoted to captain, Harrison resigned his commission and left the army in 1798.

In 1800, President John Adams appointed Harrison governor of the newly created Indiana Territory and, while in office, Harrison acquired over 55,000 square miles of Indian lands for the United States through various treaties. Harrison was well liked and that popularity grew into hero-like adulation when he destroyed a large Indian force at the Battle of Tippecanoe in 1811. Following Hull’s debacle at Detroit in August 1812, a cry went up in the West to give Harrison command of the new army being created to salvage the situation. Speaker of the House Henry Clay of Kentucky, echoing the general sentiment, wrote to Secretary of State James Monroe, “No military man in the United States combines more general confidence in the West” than Harrison, and he was appointed major general of the Kentucky militia.

To augment Harrison’s authority in raising troops, President James Madison issued him a federal brigadier general’s commission as well, with the authority to raise 10,000 men. But enthusiasm was lukewarm and Harrison was only able to build a force of 6,000 soldiers. Harrison’s plan was to consolidate his army at the Maumee Rapids and then move forward to Detroit in the spring, recognizing that his army was unprepared to launch a winter offensive. And, after General James Winchester arrived with his two regiments from Fort Defiance in mid-January 1813, the army was assembled, and it was just a matter of waiting for the coming thaw.

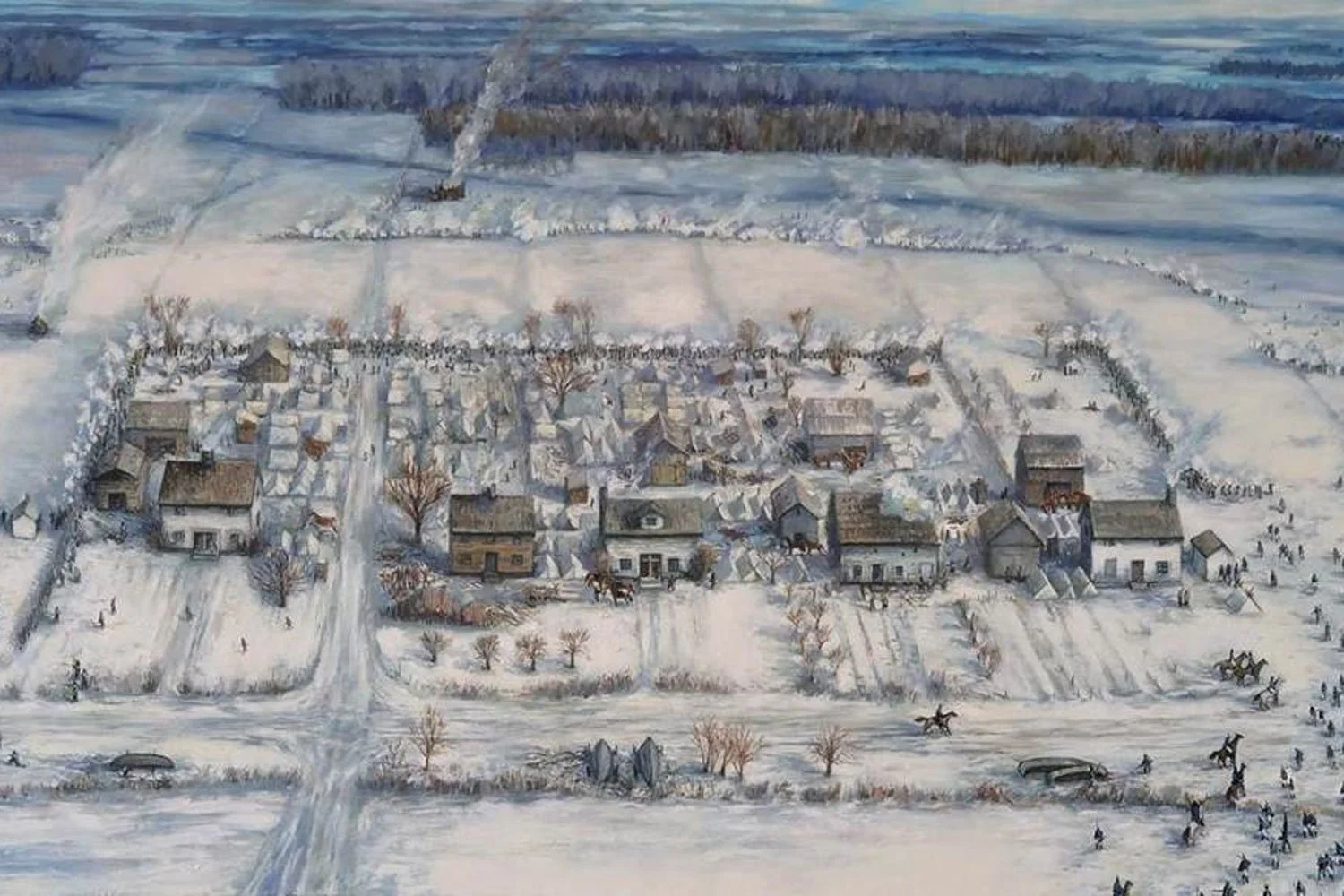

“Battle of Frenchtown.” Wikimedia.

But a few days after arriving at the rapids, Winchester received word from residents at Frenchtown, a small village thirty miles north on the River Raisin, that they were in danger of being attacked by a nearby Anglo-Indian force, and asked Winchester to come to their aid as quickly as possible. Although Harrison had instructed Winchester to not advance beyond their base camp, Winchester felt compelled to respond to their plea and notified Harrison that he planned to move forward. Harrison, recognizing the danger into which Winchester was placing his army as Frenchtown was only eighteen miles from the British stronghold at Fort Malden, began to assemble a relief force for the trouble that he sensed was coming.

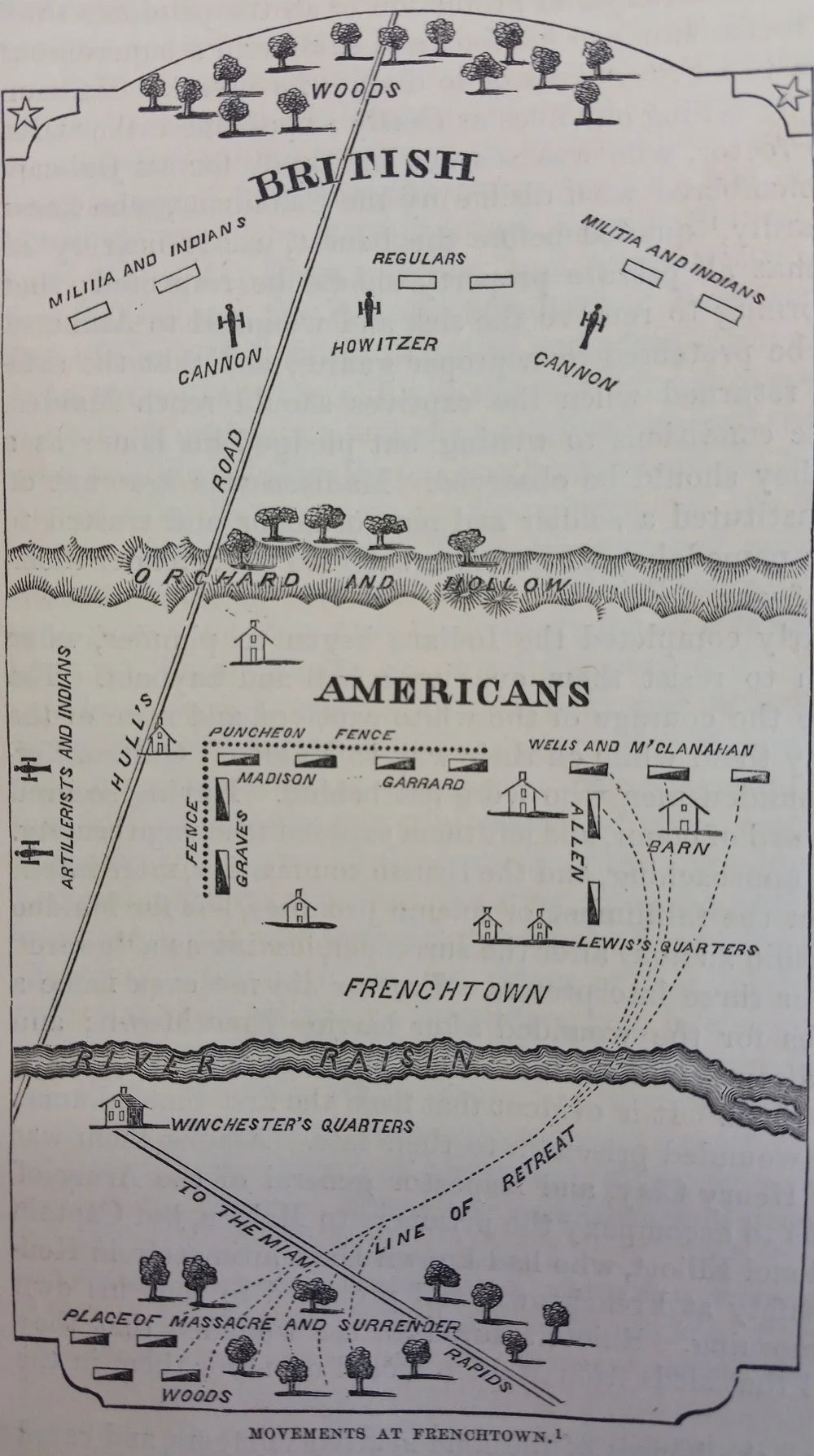

Winchester sent two detachments under Colonels William Lewis and John Allen, numbering roughly 680 men, to Frenchtown, arriving there on January 18. It was then that Lewis discovered the enemy had already arrived and occupied the village with a mixed force of 600 British, Canadian and Indian forces. Lewis ordered an immediate assault and quickly drove the British and their allies from the town and into the adjacent woods, but sharp fighting continued until dark when the British finally withdrew and headed north towards Malden.

Three days later, Winchester arrived with 300 reinforcements bringing his total strength at Frenchtown to nearly 1,000 men, but with no artillery and no axes to chop down trees and create breastworks. Winchester laid out his camp with Kentucky militiamen behind a split rail fence on the left and the regulars from the 17th and 19th Infantry Regiments on the right but completely exposed with no cover to their front. Winchester did little to improve his position and neglected to distribute additional ammunition that had recently arrived, but more importantly failed to send out scouts to keep an eye on the British. These careless mistakes would prove fatal as British Colonel Henry Proctor had not been idle and advanced with roughly of 1,200 men, half British regulars and half Indians from Fort Malden, to strike the American army. The British arrived on the outskirts of Frenchtown at dawn on January 22, but the Americans, with no distant sentries, were completely unaware of their presence.

The British commenced their attack at 5 a.m., concentrating on the exposed American position on the right, which broke when ammunition ran out. Panic set in and the men raced across the frozen River Raisin, but the Indians, many of them mounted, ran down the fleeing Americans and slaughtered them wholesale, refusing surrender pleas and taking no prisoners. It was a different story on the American left where Kentuckians with their deadly rifles repulsed three British charges and maintained their position.

Winchester, who had spent the night in a farmhouse about a half mile behind the lines, finally made it to the battlefield as the rout on the right was beginning and was captured. Colonel Proctor confronted Winchester and demanded the surrender of his entire force, including the Kentucky militiamen who were holding their own on the left, or face certain slaughter by the Indians. And Winchester, badly shaken by what he had already seen, agreed to unconditionally surrender his entire command including the Kentuckians. When the firing ceased around 11 a.m., 400 Americans had been killed and another 500 taken prisoner; incredibly, only 33 soldiers from Winchester’s entire command escaped.

Colonel Proctor, pleased with the complete victory he had gained but fearful of a counterattack by General Harrison, who was approaching with reinforcements, withdrew later that afternoon. To speed his march to Malden, Proctor left behind the more seriously wounded Americans, roughly 65 men, but with no protection. Later that night, several hundred Indians drifted back into Frenchtown, most drunk on whiskey, and over the course of the night murdered and scalped all the American wounded.

Before Harrison and his reinforcements could reach the scene, he received word of Winchester’s defeat and, thinking Proctor’s army would soon fall on his small force, Harrison retreated to a position on the Portage River to plot his next move. The Frenchtown massacre and the loss of Winchester’s force was viewed as a national disgrace, and the pressure grew on Harrison to retrieve the situation in the West.

Next week, we will discuss the British invasion of Ohio. Until then, may your motto be “Ducit Amor Patriae,” love of country leads me.

In early May 1813, Commodore Isaac Chauncey loaded General Henry Dearborn’s army onto his waiting ships and sailed back across Lake Ontario for the second phase of Dearborn’s campaign, the capture of Fort George. Between the men stationed at Fort Niagara and Dearborn’s contingent, the American force consisted of roughly 4,000 men, with command of the army falling to 26-year-old Colonel Winfield Scott, destined to be one of the great military commanders in American history.