War of 1812, Part 8: Americans Burn a Capital

The man to whom President James Madison and Secretary of War William Eustis gave command of the overall war effort for the War of 1812 was Henry Dearborn from New Hampshire. In addition to the overall command, Dearborn was assigned the right wing of the three-pronged American attack into Canada, up the Lake Champlain corridor to the St. Lawrence River and then onward to Montreal. Arguably, this invasion sector was the most critical, as the St. Lawrence represented the only means of communication between Lower Canada and Upper Canada. If the Americans were able to choke off the St. Lawrence at any point, all supplies for Upper Canada would cease flowing, and with that would come an end to the war. Many noted that this task was not formidable, in fact the Quebec Gazette noted “a few cannon judiciously posted or even musketry could render the communication impracticable without powerful escorts. It is needless to say that no British force can remain in safety or maintain itself in upper Canada without a ready communication with the lower province.”

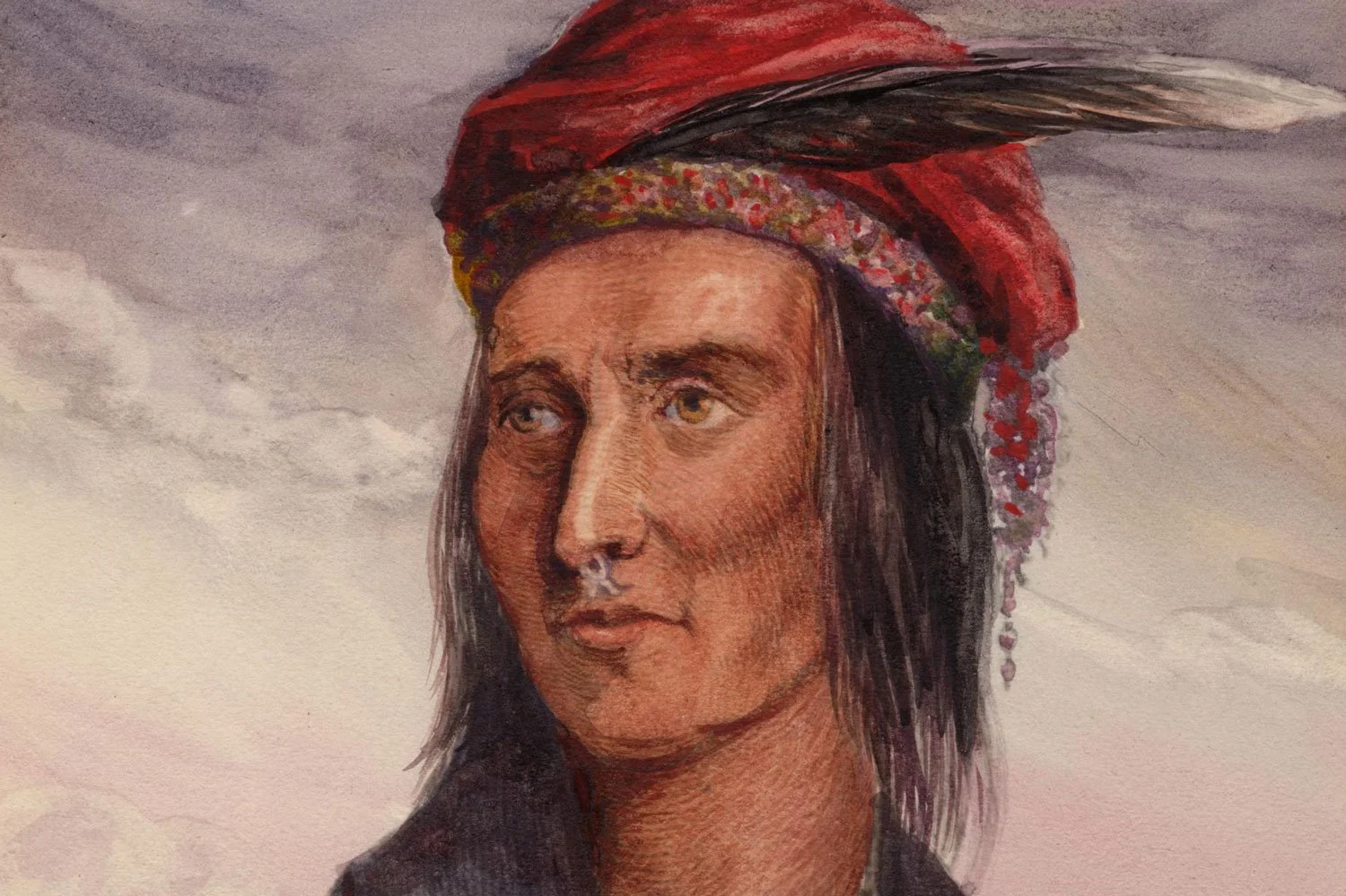

“Zebulon Pike.” Wikimedia.

Dearborn, who was a doctor prior to the American Revolution, began his military career in 1775 as a Captain of New Hampshire militiamen, fighting alongside General John Stark at the Battle of Bunker Hill, and Dearborn's competence and bravery were soon noted. Dearborn accompanied Benedict Arnold on the failed invasion of Quebec in 1775, performed heroically at Saratoga in 1777, and was at Yorktown when Lord Cornwallis surrendered his British Army in 1781, rising to the rank of Lieutenant Colonel. Following the war, Dearborn returned to his home, a farm on the Kennebec River, but was soon back in public service, serving two terms in Congress as a Democratic-Republican representative from Massachusetts and then eight years as President Thomas Jefferson’s Secretary of War. Following that stint, Dearborn was appointed collector of the port of Boston by President James Madison and served in that capacity until Madison appointed him to command the United States Army in the War of 1812.

The initial campaigns of the war had not gone well, in part due to the lethargy shown by the often ill 61-year-old General Dearborn. In January 1813, Secretary of War William Eustis was replaced by John Armstrong, an energetic former officer in the American Revolution who seemed to be always mired in controversy including the Newburgh Conspiracy. Despite his abilities, Armstrong was not a man who was widely trusted as seen by the narrowness of his confirmation vote of 18 to 15 in the U.S. Senate. But Armstrong soon pushed Dearborn to begin an active campaign for the invasion of Canada and ordered the aging General to assemble an army at Sackett’s Harbor, a recently expanded navy yard at the mouth of the St. Lawrence River and directly across from the British base at Kingston.

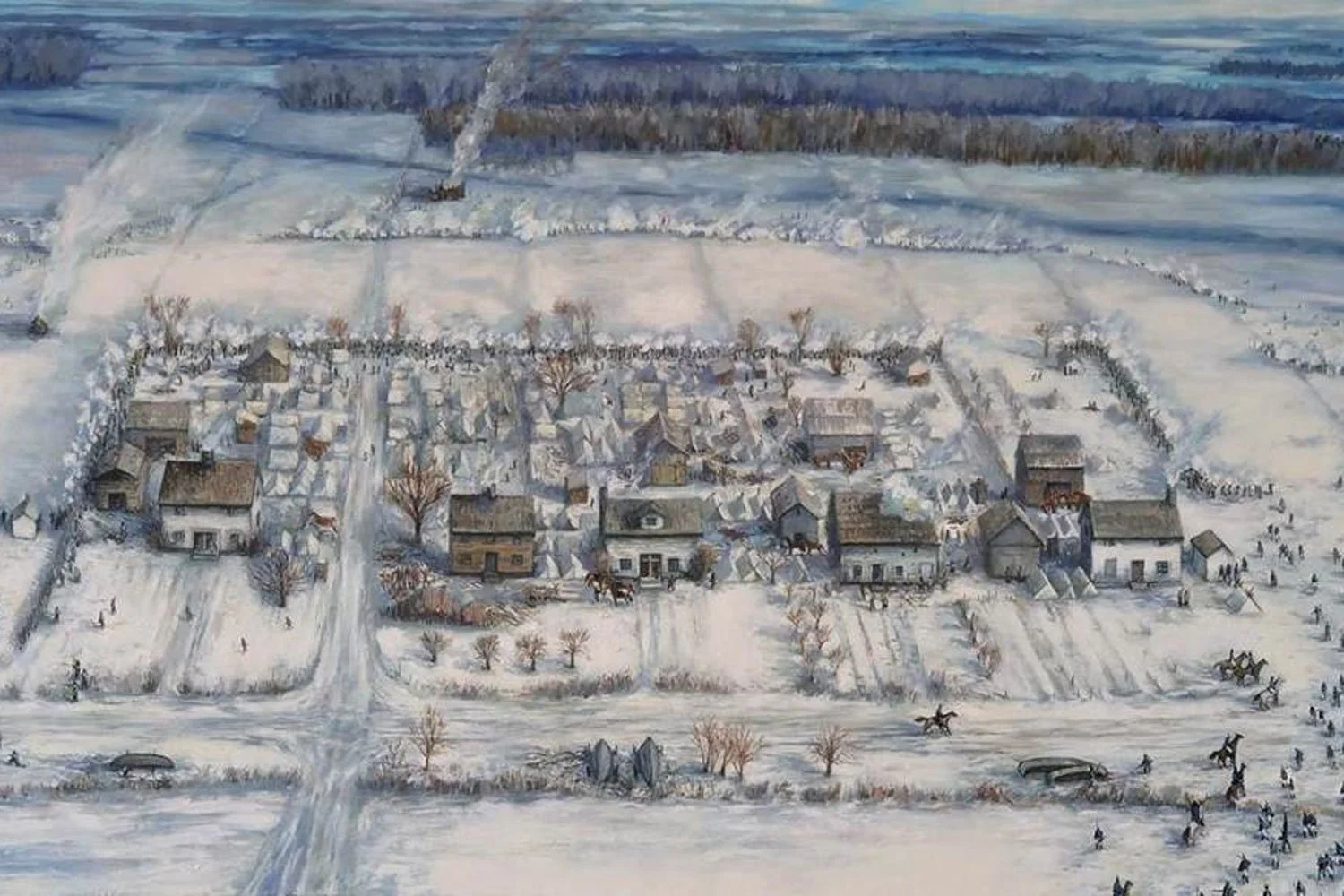

By early April, Dearborn had assembled over 8,000 men at Sackett’s Harbor and Dearborn and Commodore Isaac Chauncey, commander of the American fleet on Lakes Ontario and Erie, decided to act before the spring thaw when British reinforcements were expected to arrive up the frozen St. Lawrence. Their plan was to cross the lake and destroy the British naval yard at York, located on the north shore of Lake Ontario at the head of a beautiful harbor and the capital of Upper Canada, and then recross the lake and reduce British-held Fort George, the main British outpost on Lake Ontario, at the mouth of the Niagara River. On April 25, the flotilla, led by Chauncey with 1,700 men under Dearborn’s command, pushed off from Sackett’s Harbor and arrived at York two days later. Dearborn was ill and bedridden, and the command of the landing party passed to General Zebulon Pike, a famous explorer and considered by many to be the brightest Brigadier General in the United States Army. Facing the American invasion force was Major General Roger Sheaffe, the Lieutenant Governor of Upper Canada, with 600 men, half regulars and half militia. The defenses of the town were surprisingly poorly prepared to receive an assault as several cannons were without trunnions and several others were not mounted on carriages.

Still stung from the embarrassing setbacks the previous year, Pike exhorted his men to “be mindful of the honor of the American arms, and the disgraces which have recently tarnished our arms, and endeavor by a cool and determined discharge of their duty, to support the one and wipe off the other.” The Americans landed at 8 a.m. and, by late morning, Sheaffe recognized his small force could not hold the town and withdrew his regulars across the Don River, leaving the Canadian militiamen to strike the best deal they could with the Americans. But prior to leaving, Sheaffe rigged the powder magazine with 74 tons of iron shells and 300 barrels of gunpowder to explode rather than let it fall into American hands. Around 1 p.m., the charge denoted and beams, metal, and stone from the magazine flew off in every direction for 500 yards, killing or wounding over 200 Americans and nearly as many Brits. Sadly, one of the American casualties was General Pike whose chest was crushed by a large boulder dislodged by the explosion.

Although the Americans were temporarily confused, they quickly regained their ranks and drove the remaining British from town. Angered by the explosion, some Americans set fire to the town’s public buildings including the Government House and Legislative Assembly, and this destruction of York’s public buildings was later used as justification for the British burning Washington. Although the naval yard at York had been destroyed, the expedition was costly as the Americans suffered nearly 300 casualties, most from the magazine explosion, while the British lost 400 men, including 290 Canadian militiamen taken prisoner. But most importantly, the Americans had tasted the sweetness of victory for the first time in the war at the Battle of York.

Next week, we will discuss the Battles of Stoney Creek and Beaver Dams. Until then, may your motto be “Ducit Amor Patriae,” love of country leads me.

Hello America!

Subscribe to receive weekly complimentary articles and videos delivered straight to your inbox.

The man to whom President James Madison and Secretary of War William Eustis gave command of the overall war effort for the War of 1812 was Henry Dearborn from New Hampshire. In addition to the overall command, Dearborn was assigned the right wing of the three-pronged American attack into Canada, up the Lake Champlain corridor to the St. Lawrence River and then onward to Montreal. Arguably, this invasion sector was the most critical, as the St. Lawrence represented the only means of communication between Lower Canada and Upper Canada.