War of 1812, Part 1: A Divided America Goes to War

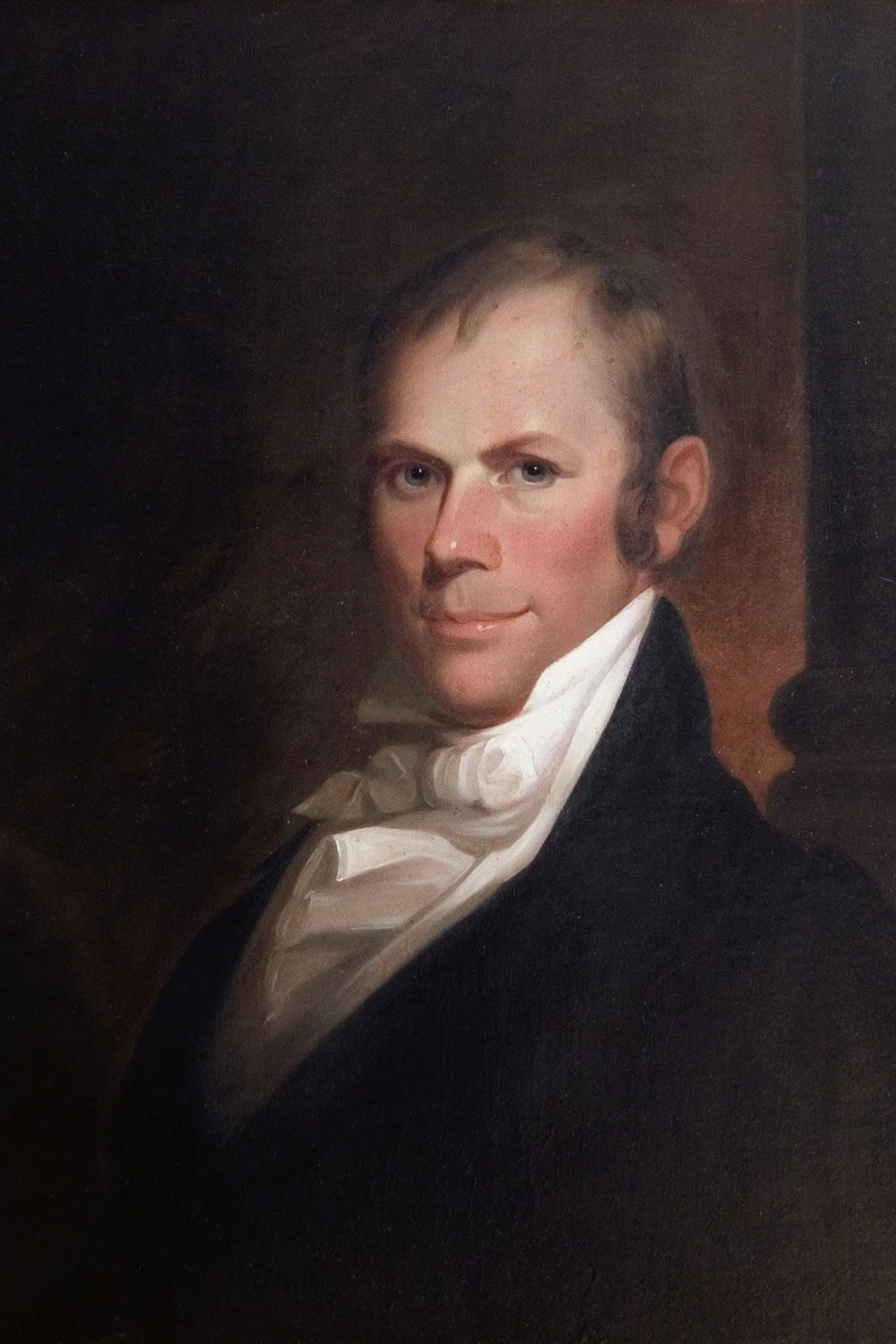

In June of 1812, President James Madison asked Congress to declare war on Great Britain for refusing to honor American maritime rights. In some ways, Madison’s hand was forced by the young firebrands who made up the Twelfth Congress with its unprecedented seventy new members and dominated by Democratic-Republicans, men like John C. Calhoun of South Carolina, Felix Grundy of Tennessee, and Richard M. Johnson of Kentucky. But the ringleader was thirty-four-year-old Henry Clay of Kentucky, who was elected Speaker of the House by his fellow war hawks.

But support was not unanimous, as New England, dominated by Federalists, failed to see the need for the war and fully recognized that the country was woefully unprepared for a conflict due to the neglect of the army and navy by the Jefferson and Madison administrations. Additionally, although the main issue voiced by the Madison administration was violations of American rights on the high seas, the American plan called for a land war against British Canada to secure them. That seemed odd to many of Madison’s critics such as John Randolph of Roanoke, who argued that American expansionism was the true motive behind the declaration of war.

“Henry Clay.” Wikimedia.

But Democratic-Republicans could not be dissuaded as they considered Canada relatively weak with only 500,000 residents, compared to the United States population of 7,500,000, and lightly defended by only 5,000 British regulars. To the war Republicans, Canada seemed an easy conquest, one by which the United States could punish the British for their eternal arrogance but more importantly expand our national boundaries and expel the British from North America once and for all. Clay boldly declared that the Kentucky militia alone could conquer Canada and Thomas Jefferson, the patriarch of the party, commented that “the acquisition of Canada this year, as far as the neighborhood of Quebec, will be a mere matter of marching.” Consequently, when the vote on Madison’s request was taken on June 18, 1812, it was the closest vote in our country’s history on a declaration of war with the Senate passing the measure largely along party lines by a 19 to 13 margin, while in the House the vote was 79 to 49.

Interestingly, Great Britain wanted this war even less than the United States as its focus was on Napoleon, who still dominated Europe. Perhaps more importantly, the British army fighting Napoleon in the Peninsular War was largely being fed by grain and meat imported from the United States. Additionally, British merchants urged their government to avoid a war that would cripple trade with America. Consequently, on June 16, two days before the United States declared war, Parliament rescinded its Orders in Council, one of the main reasons why Americans supposedly went to war. Word of the British decision reached Washington the following month but “the dogs of war” had been loosed and President Madison, never a strong leader, did not have the will to push back against the war hawks and stem the tide of martial emotion.

But more importantly, the nation was simply not prepared for a conflict, especially not against the world’s greatest power. The army was in a deplorable state and, at the start of the war, was comprised of only 7,000 regulars and another 5,000 men in volunteer regiments, scattered in garrisons across the vast country. Recognizing the need to increase this force, Congress voted to expand the regular army to 35,000 soldiers and levy another 100,000 volunteers from state militias. But authorizing an army and filling the ranks are two different things, and the Madison administration struggled to meet its enlistment goals throughout the course of the war. Consequently, the burden of fighting the war largely fell to state militias, who tended to be less reliable in battle than the regulars and whose short-term enlistments always seemed to expire at the most inopportune times.

Initially, the leadership of the army was weak as President Madison appointed men to its highest positions based on political leanings rather than on their talents. His Secretary of War was William Eustis, a rare New England Republican, who had served in the American Revolution as a hospital surgeon but seemed to have no real qualifications for his position. Madison selected 62-year-old Henry Dearborn, then serving as the tax collector for the Port of Boston, as the overall commander of the army and 63-year-old Thomas Pinckney as his second in command; neither man had seen active military service since the American Revolution. His other key generals were also political appointees, including William Hull, Stephen Van Rensselaer, and James Winchester, all roughly 60 years of age and well past their prime. It would not be until disaster on the battlefield and national disappointment in these aged generals that Madison, out of necessity, would turn to younger, more talented men such as Jacob Brown, Winfield Scott, Andrew Jackson, and William Henry Harrison.

The Secretary of the Navy was Paul Hamilton, a party stalwart and former governor of South Carolina who had fought under Francis Marion in the American Revolution but had no naval experience, and his department was unprepared for war due to the Jefferson and Madison administrations hostility to a standing navy. Consequently, the navy had only sixteen warships in 1812, including eight frigates but no ships of the line, the main battle wagon during the age of sail. To make matters worse, most of the frigates were in dry dock in various states of repair. But importantly, the men who had captained the ships so well in the Barbary War were still in their prime and eager for laurels, men such as Isaac Hull, Stephen Decatur, and Oliver Hazard Perry. In comparison, Great Britain possessed the greatest navy in the world, numbering over 1,000 vessels, including 150 ships of the line and 164 frigates. But as with the British Army, the Royal Navy’s efforts were concentrated in Europe and initially the British had only 80 warships on the American station, certainly more than the Americans possessed but not nearly enough to cover the vast area from Halifax to the Leeward Islands. It would not be until 1814, when ships were released from the European theater, that the full brunt of the Royal Navy’s blockade of the American coast was felt.

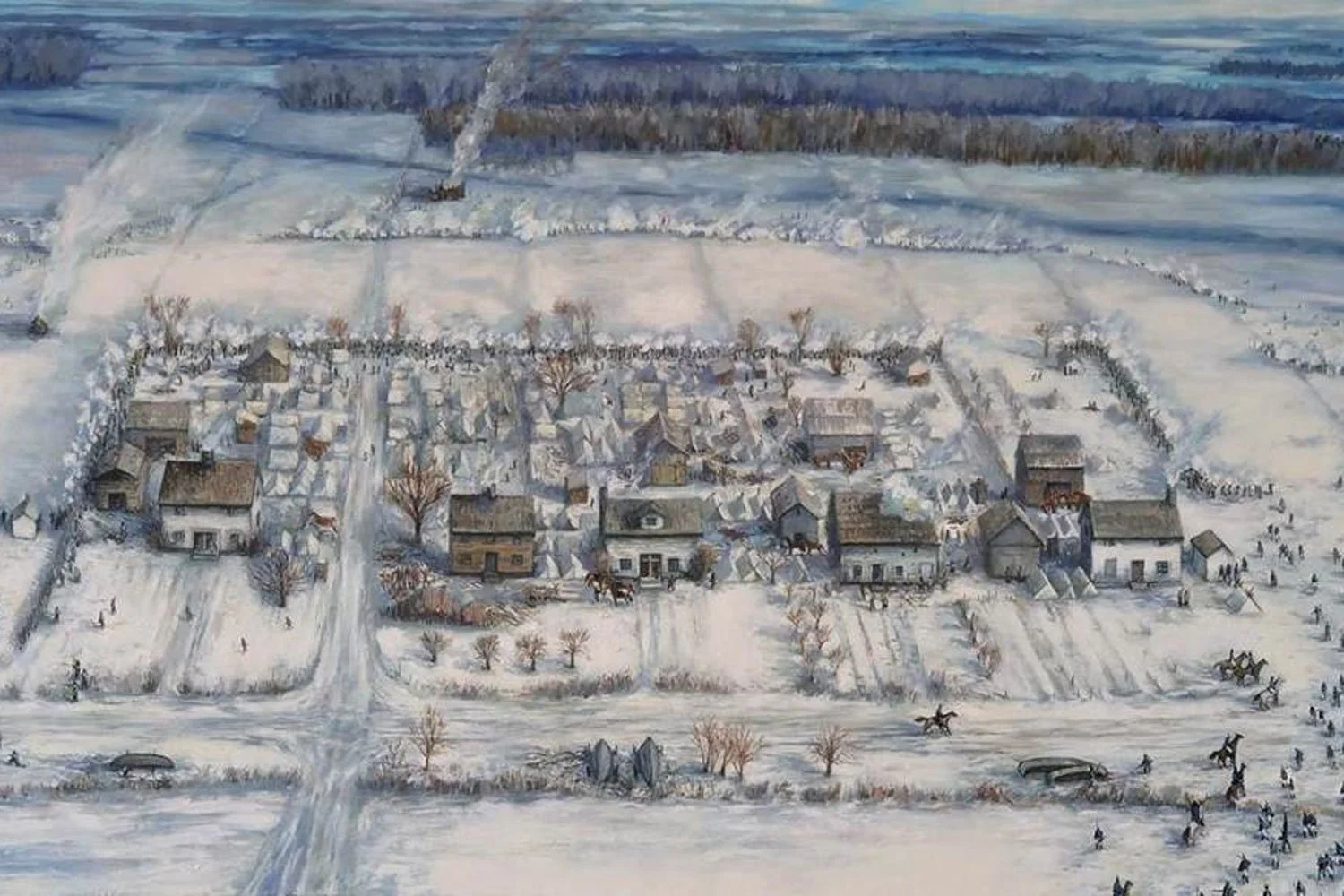

The American strategy called for a three-prong invasion of Canada; one led by Dearborn to capture Montreal and close the St. Lawrence River, thereby severing the British supply line to Upper Canada, and another led by Van Rensselaer across the Niagara River to secure Lake Ontario. But it was the western theater, emanating from Detroit into Upper Canada, that would initiate the land war.

Next week, we will discuss the surrender of Detroit. Until then, may your motto be “Ducit Amor Patriae,” love of country leads me.

The center thrust of the three-prong American advance into Canada was along the Niagara River frontier. This thirty-five-mile stretch was the most contested piece of real estate during the War of 1812 and would change hands several times over the course of the war. Secretary of War William Eustis entrusted the command of this sector to Stephen van Rensselaer.