Road to War, Part 7: Madison Changes Sides

On March 4, 1789, the Constitutional government, largely the creation of James Madison’s fertile mind, took effect. Naturally, Madison was there at the start to help President George Washington implement and execute this new government. But within a matter of just a few years, Madison would be opposed to the new administration that he helped bring to power as he saw the federal government going in a direction he had not envisioned. Madison’s about face, arguably the greatest political transformation by a national figure in American history, came about largely because of differing ideas regarding what the new government should look like.

In February 1789, Madison was elected to the House of Representatives for the first Congress under the new Constitution, defeating James Monroe, an avowed anti-Federalist and future fifth President of the United States. In addition to becoming a leader in the House, Madison was instrumental in helping to shape the Washington administration, even drafting President Washington’s inaugural address. Madison also helped the President form his cabinet by recommending Alexander Hamilton for Secretary of the Treasury and Thomas Jefferson for Secretary of State.

But Madison’s primary job was to organize and oversee the House. As promised during the Constitutional Convention, one of Madison’s first acts was to propose a series of amendments to guarantee to the people the personal liberties so recently won in the American Revolution. And in September, Madison’s twelve amendments were approved by both chambers of Congress and ultimately ten of those were ratified by the states, known to history as the Bill of Rights. But a break quickly developed between the Madison-Jefferson faction, soon to be known as Democratic-Republicans, and Hamilton's Federalists over Hamilton's national credit plan that included the assumption of debt incurred by the states during the war. Madison felt that debt assumption was not authorized by the Constitution, but Hamilton argued that the “necessary and proper” clause found in Section 8, Article I gave implied powers to the federal government to execute and carry out the enumerated responsibilities, a position that Madison himself once supported.

“Alexander Hamilton.” National Portrait Gallery, Smithsonian Institution.

During the debate over debt assumption, there was another discussion taking place regarding the permanent location of the national capital. Naturally, Madison and Jefferson as Virginians favored a more southerly capital while others, especially those from New York, wanted to keep the capital in New York City. To gain the votes necessary to overcome opposition to his debt assumption plan, Hamilton agreed to persuade his fellow northerners to support placing the nation's capital permanently on the banks of the Potomac in the yet to be created Federal City. And to persuade Pennsylvania congressmen to support this deal, it was further agreed that the capital would reside in Philadelphia for ten years, the Pennsylvanians believing that once the capital was established in Philadelphia it would never move.

As Madison came further under Jefferson’s sway and viewed first-hand Hamilton’s implementation of the new Constitution, Madison’s view shifted from a fear of too much state power to a fear of an ever-expanding federal government. While Hamilton favored executive supremacy, Madison sought legislative supremacy. Whereas Hamilton wanted power vested in a few select men or even just one, Madison wanted power vested in the many, or the people. It did not help that Hamilton admired all things British, including their form of government, while Madison detested the British with an almost unhinged hatred. Unfortunately, these irreconcilable differences created an impasse between two devoted Patriots who both wanted only the best for the United States.

The final split between Madison and Hamilton came in 1791 when Hamilton proposed a National Bank to bring creditworthiness to the nation and to stabilize the chaotic currency system then in place. While recognizing the need, Madison strongly opposed Hamilton's proposal, declaring that the Constitution did not explicitly authorize a national bank. As with his debt assumption argument, Hamilton justified the creation of the bank by invoking the “necessary and proper” clause of the Constitution. Hamilton's bank bill passed in Congress, supported by northern commercial interests but opposed by southern agrarian interests. The bill then went to President Washington’s desk who asked both Hamilton and Jefferson to submit arguments for and against the constitutionality of the bank. As part of his dissertation, Hamilton cited Madison’s own compelling argument in Federalist 44 regarding the theory behind the “necessary and proper” clause in the Constitution. Madison had written that “no axiom is more clearly established in law, or in reason, then that wherever the end is required, the means are authorized; wherever a general power to do a thing is given, every particular power necessary for doing it, is included.” Although torn by the decision, President Washington, on the last day available to him, signed the Bank Bill of 1791 into law.

For Madison, this legislation represented another step down the dangerous road of an all-powerful and tyrannical central government and moved Madison further from his nationalist roots of the 1780s, and with Madison’s radicalization came a lesser role in the Washington administration. Madison was increasingly seen as the leader of the Democratic-Republican opposition party and began to create an alliance with like-minded leaders in New York such as Aaron Burr, Robert Livingston, and Governor George Clinton, all anti-Hamiltonians. He even helped establish a strongly partisan newspaper, with Phillip Freneau as its editor, called The National Gazette, arguably marking the start of party politics in the United States. Hamilton, who once collaborated so closely with Madison, was disappointed at Madison’s shift in political perspective, writing that Madison’s and Jefferson’s views were “unsound and dangerous. They had a womanish attachment to France and a womanish resentment against Great Britain.”

Madison retired from the House in 1797 but enjoyed only a short retirement before returning to the national stage in 1801 as President Thomas Jefferson’s Secretary of State. For eight years Madison served in this capacity and was groomed to succeed Jefferson in the White House. Finally in 1809, James Madison became the 4th president of the United States, a presidency largely spent dealing with issues with Great Britain, but his first major problem was an Indian War in the Old Northwest.

Next week, we will discuss Tecumseh’s War. Until then, may your motto be “Ducit Amor Patriae,” love of country leads me.

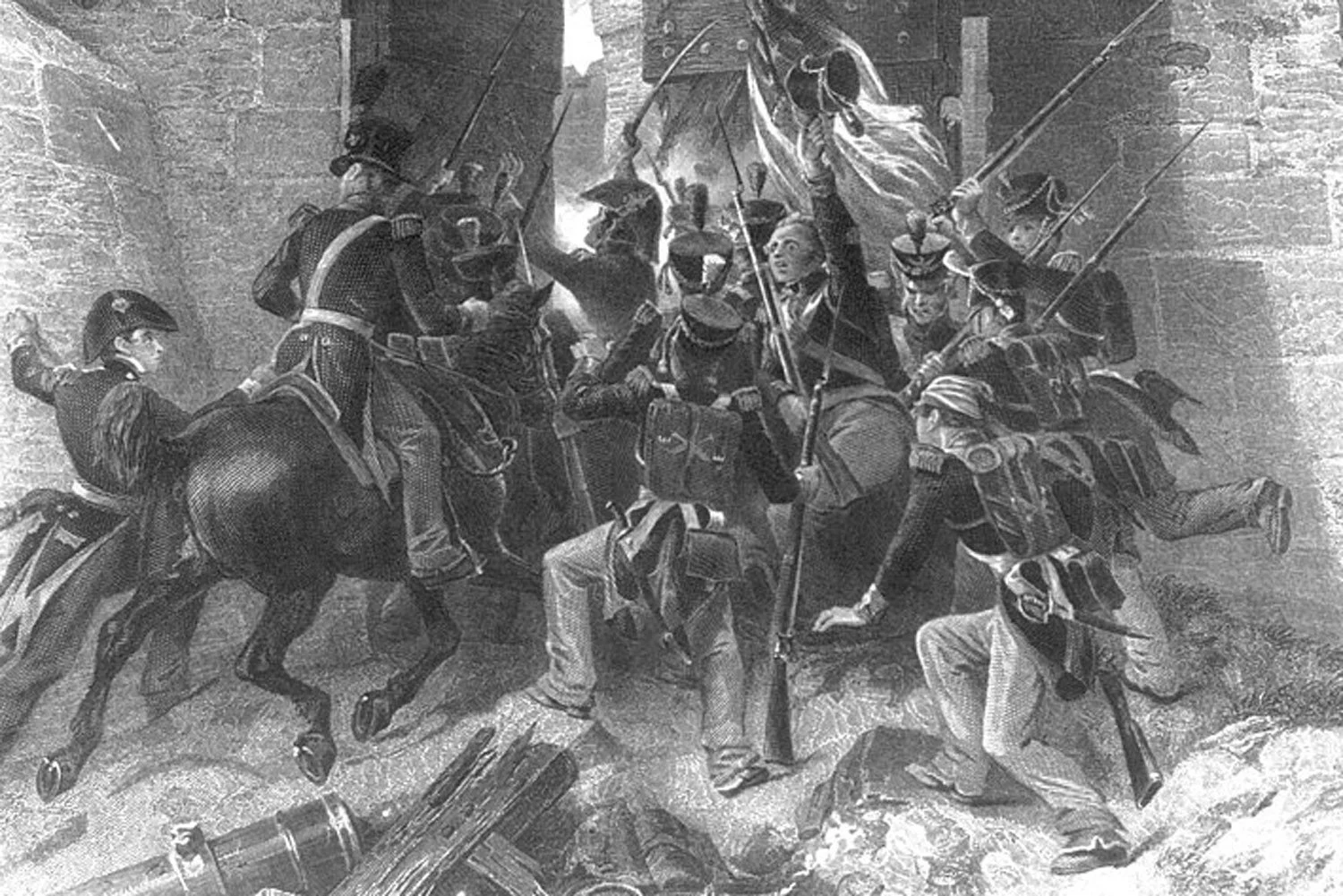

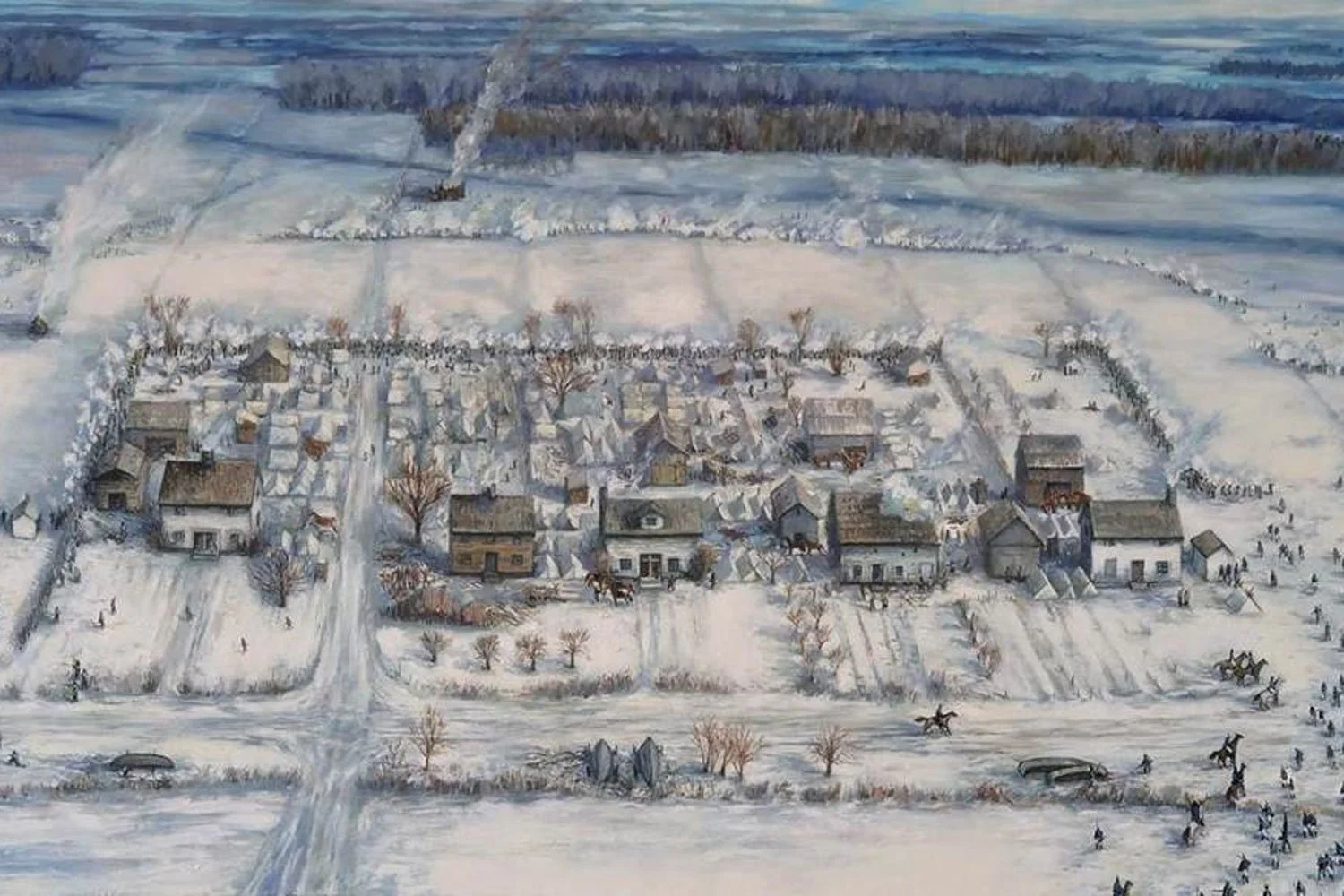

While General Henry Dearborn was trying to make headway along the Niagara front, the British were busy launching an offensive of their own against Sackett’s Harbor. This was not the first British attack on the American outpost, as the previous summer, on July 19, a British fleet had attempted to destroy Sackett’s Harbor’s critical navy yard, but the British were repulsed in that attack which marked the first armed engagement in the War of 1812.