War of 1812, Part 5: We Have Met the Enemy

The key to controlling Upper Canada in the War of 1812 was gaining naval mastery of the Great Lakes. Secretary of the Navy William Jones appointed Oliver Hazard Perry to command the American fleet on Lake Erie. His adversary was Captain Robert Barclay, whose fleet consisted of six ships, the largest of which was the Detroit with nineteen guns and the Queen Charlotte with seventeen guns. In comparison, Perry’s fleet consisted of nine warships, including two twenty-gun brigs: the Lawrence, which Perry named his flagship, and the Niagara, which Perry assigned to Captain Jesse Elliott. On September 10, 1813, just before noon, the British long guns on the Detroit opened the engagement and Perry gave the order to close with the enemy.

War of 1812, Part 4: British Invade Ohio

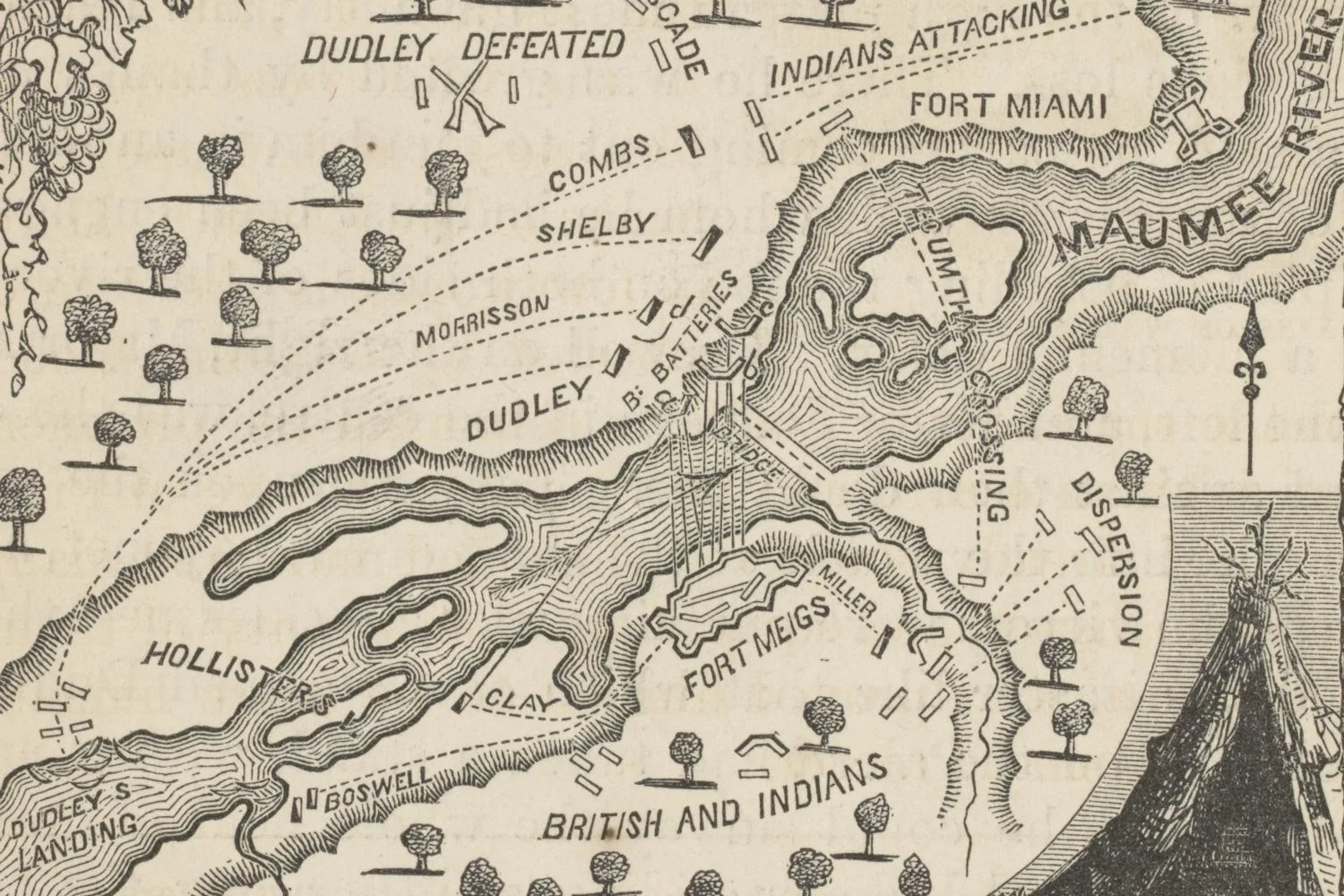

Following the American disaster at Frenchtown, General William Henry Harrison, gathered another force to turn the tide in the west. In February, Harrison tasked Major Eleazer Wood to construct Fort Meigs on the banks of the Maumee River. On May 1, a British army including 1,000 regulars and militia under General Henry Proctor and 1,500 Indians led by Tecumseh initiated a siege of Fort Meigs. After pounding the fort with artillery for four days, Proctor sent in a demand that Harrison surrender the fort or face the consequences. Despite outnumbering the Americans, Proctor lost heart and abandoned the siege, retreating to Fort Malden. But he returned to Fort Meigs in July with a larger force including 400 regulars and 3,000 Indians. After failing to lure the Americans from the safety of the fort, Proctor called off the attack and took his force up the Sandusky River to Fort Stephenson which appeared to be an easier target.

War of 1812, Part 3: Debacle on the River Raisin

Following the surrender of Detroit, William Henry Harrison, governor of the Indiana Territory, was named as Hull’s replacement. Harrison consolidated his army at the Maumee Rapids and planned to move on Detroit in the spring. But in mid-January 1813, General James Winchester, one of Harrison’s officers, received word that Frenchtown, a small village thirty miles north on the River Raisin, was in danger of being attacked. Although Harrison had instructed Winchester not to advance beyond their base camp, Winchester felt compelled to respond. Winchester laid out his camp with Kentucky militiamen behind a split rail fence on the left but the regulars on the right were completely exposed with no cover to their front. Importantly, Winchester failed to send out scouts to keep an eye on the British. Undetected by the Americans, the British attacked at dawn on January 22.

War of 1812, Part 2: The Surrender of Detroit

President James Madison named William Hull, governor of the Michigan Territory, to command the western war effort in the War of 1812. Hull’s primary mission was to capture Fort Malden, the main British outpost in the region. Hull’s task was formidable for several reasons, but primarily because his supply line stretched for 200 trackless miles through hostile Indian country. Hull arrived at Detroit on July 5 and, one week later, crossed his army into Canada and moved south to capture Fort Malden. While waiting for his field guns to arrive to commence the assault, Hull received the disturbing news that Fort Mackinac had been captured by the British, meaning that several thousand Indians who had participated in that attack would soon be coming down from the north. On August 15, General Isaac Brock, governor of Ontario, appeared with 1,500 men on the opposite bank of the Detroit River and demanded Hull’s surrender.

War of 1812, Part 1: A Divided America Goes to War

In June of 1812, President James Madison asked Congress to declare war on Great Britain for refusing to honor American maritime rights. Madison’s hand was forced by the young firebrands who made up the Twelfth Congress. Support for the war was not unanimous, as New England, dominated by Federalists, strongly opposed the conflict. But to the Democratic-Republicans, Canada seemed an easy conquest, with Thomas Jefferson stating that “the acquisition of Canada…will be a mere matter of marching.” When the vote on Madison’s request was taken on June 18, 1812, it was the closest in our country’s history on a declaration of war.

Road to War, Part 8: The Fifty-Year War for the Old Northwest

At the conclusion of the French and Indian War in 1763, the British gained possession of all French lands in North America, including the Northwest Territory, which was then part of Canada. Unlike the French who allied themselves with the Indian nations, the British treated the natives as a conquered people and for the next fifty years there was continuous conflict between white settlers and Indians in this region.

Road to War, Part 7: Madison Changes Sides

In February 1789, James Madison was elected to the House of Representatives for the first Congress under the Constitution. Besides leading the House, Madison helped shape the Washington administration, drafting President Washington’s inaugural address and recommending Alexander Hamilton for Secretary of the Treasury and Thomas Jefferson for Secretary of State. But a break soon developed between the Madison-Jefferson faction, known as Democratic-Republicans, and Washington’s Federalist administration over Hamilton's plan for the national government to assume state debt incurred during the war.

Road to War, Part 6: James Madison, Father of the Constitution

In 1787, James Madison and Alexander Hamilton organized the Constitutional Convention not simply to fix flaws in the Articles of Confederation but rather to create a new vibrant national government under which the United States could flourish. The most critical issue to be resolved was how representation in Congress would be determined, for with more representatives came more power. Madison’s Virginia Plan comprised fifteen resolutions that became the basis for our constitution and called for representation according to population in both the House and the Senate. After the convention, Madison, along with Alexander Hamilton and John Jay, drafted eighty-five essays known as The Federalist Papers, the greatest collection of writings ever on a federal constitutional government. No other Founding Father played such an outsized role in creating our nation’s Constitution.

Road to War, Part 5: James Madison Embraces the American Cause

In 1774, Parliament passed the Coercive Acts, which effectively shut down the city of Boston and revoked the historic charter of Massachusetts, replacing it with royal authority. This affront to the liberties of American colonists greatly troubled Madison and pushed him into the camp of American separatists, and it was here that Madison found his true calling and to which he would devote the rest of his life. Madison was elected to the Confederation Congress, where his brilliant mind and extraordinary work ethic soon gained the young Virginian the admiration of his fellow congressmen and made him a leader in the national assembly.

Road to War, Part 4: The Early Life of James Madison

James Madison was one of our nation’s most important founding fathers and played a critical role in the shaping United States. Known to history as the “Father of the Constitution,” Madison’s brilliant mind was among the finest the nation has ever produced and his grasp of the theories of republican government and his efforts to implement those theories were unparalleled.

Creating the Constitution, Part One: Enabling the Government to Control the Governed

It is important to understand the challenges faced by the Founders in creating our new federal system. As James Madison wrote, "the great difficulty lies in this: you must first enable the government to control the governed; and in the next place oblige it to control itself.”