War of 1812, Part 2: The Surrender of Detroit

President James Madison named William Hull, governor of the Michigan Territory, to command the western war effort in the War of 1812. Hull’s primary mission was to capture Fort Malden, the main British outpost in the region. Hull’s task was formidable for several reasons, but primarily because his supply line stretched for 200 trackless miles through hostile Indian country. Hull arrived at Detroit on July 5 and, one week later, crossed his army into Canada and moved south to capture Fort Malden. While waiting for his field guns to arrive to commence the assault, Hull received the disturbing news that Fort Mackinac had been captured by the British, meaning that several thousand Indians who had participated in that attack would soon be coming down from the north. On August 15, General Isaac Brock, governor of Ontario, appeared with 1,500 men on the opposite bank of the Detroit River and demanded Hull’s surrender.

Tom Hand, creator and publisher of Americana Corner, discusses the surrender of Detroit and why it still matters today.

Images courtesy of the National Portrait Gallery - Smithsonian Institution, New York Public Library, World History Encyclopedia, Yale University Art Gallery, Library of Congress, Wikimedia.

The man to whom President James Madison and Secretary of War William Eustis gave command of the overall war effort for the War of 1812 was Henry Dearborn from New Hampshire. In addition to the overall command, Dearborn was assigned the right wing of the three-pronged American attack into Canada, up the Lake Champlain corridor to the St. Lawrence River and then onward to Montreal. Arguably, this invasion sector was the most critical, as the St. Lawrence represented the only means of communication between Lower Canada and Upper Canada.

The center thrust of the three-prong American advance into Canada was along the Niagara River frontier. This thirty-five-mile stretch was the most contested piece of real estate during the War of 1812 and would change hands several times over the course of the war. Secretary of War William Eustis entrusted the command of this sector to Stephen van Rensselaer.

On September 12, 1813, General William Henry Harrison received word of Captain Oliver Hazard Perry's great victory on Lake Erie two days before. Recognizing that the Navy had done their part and cleared the lake of British warships, Harrison knew the time had finally come for the invasion of Upper Canada, and the General immediately put the wheels in motion to strike the British while he held the advantage.

The key to controlling Upper Canada in the War of 1812 was gaining naval mastery of the Great Lakes, especially Lakes Erie and Ontario. Given the lack of adequate roads in that area, neither side could hope to sustain an army of any size in the field without the ability to deliver supplies and reinforcements via these lakes. As 1813 opened, the British were in firm control of both and, despite the clamor of the Madison administration and Americans living west of the Appalachians to invade Canada, General William Henry Harrison, commander of the western army, was painfully aware that he must wait for a situational change on Lake Erie before beginning his advance.

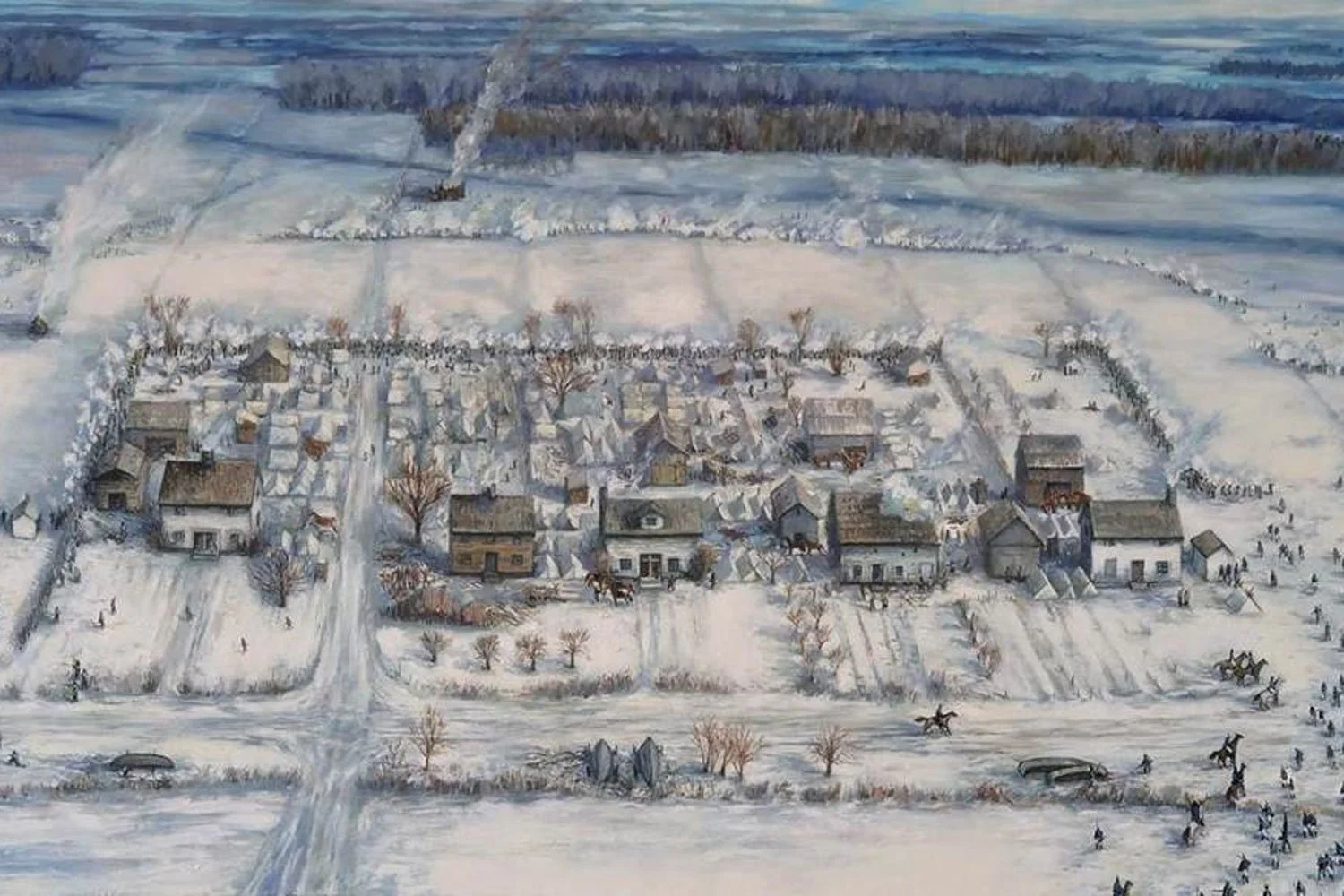

Following the American disaster at Frenchtown, General William Henry Harrison gathered another force to turn the tide in the West. On February 1, 1813, Harrison returned to the rapids of the Maumee with 1,800 Pennsylvania and Virginia militiamen and tasked Major Eleazer D. Wood of the Engineers, an early graduate of West Point, to construct Fort Meigs. Wood finished the fort by the end of the month, but unfortunately the enlistments of most of the men expired at the same time and Harrison was left with a formidable fort but a garrison of less than 500 soldiers.

Following General William Hull’s ignominious surrender of Fort Detroit, the outlook for the United States in Upper Canada was bleak. The western army essentially had been eliminated with Hull’s surrender, and a new army had to be raised. But perhaps more importantly, a new commander had to be found, and that man would be William Henry Harrison, governor of the Indiana Territory and acclaimed in the West as the hero of Tippecanoe.

Early in 1812, when war with Great Britain seemed imminent, President James Madison named William Hull, the Governor of the Michigan Territory and a veteran of the American Revolution, to command the western war effort. Hull was a reluctant warrior who initially declined the post recognizing his best years were behind him, but when President Madison could not find a suitable replacement, Hull agreed to take the command.

In June of 1812, President James Madison asked Congress to declare war on Great Britain for refusing to honor American maritime rights. In some ways, Madison’s hand was forced by the young firebrands who made up the Twelfth Congress with its unprecedented seventy new members and dominated by Democratic-Republicans.

The last great battle between Indians in the old Northwest Territory and the forces of the United States, and one of the most consequential in our nation's early decades, was the Battle of Tippecanoe, fought on November 7, 1811, between Shawnee, Potawatomi, and Kickapoo warriors and American troops led by General William Henry Harrison, the Governor of the Indiana Territory.

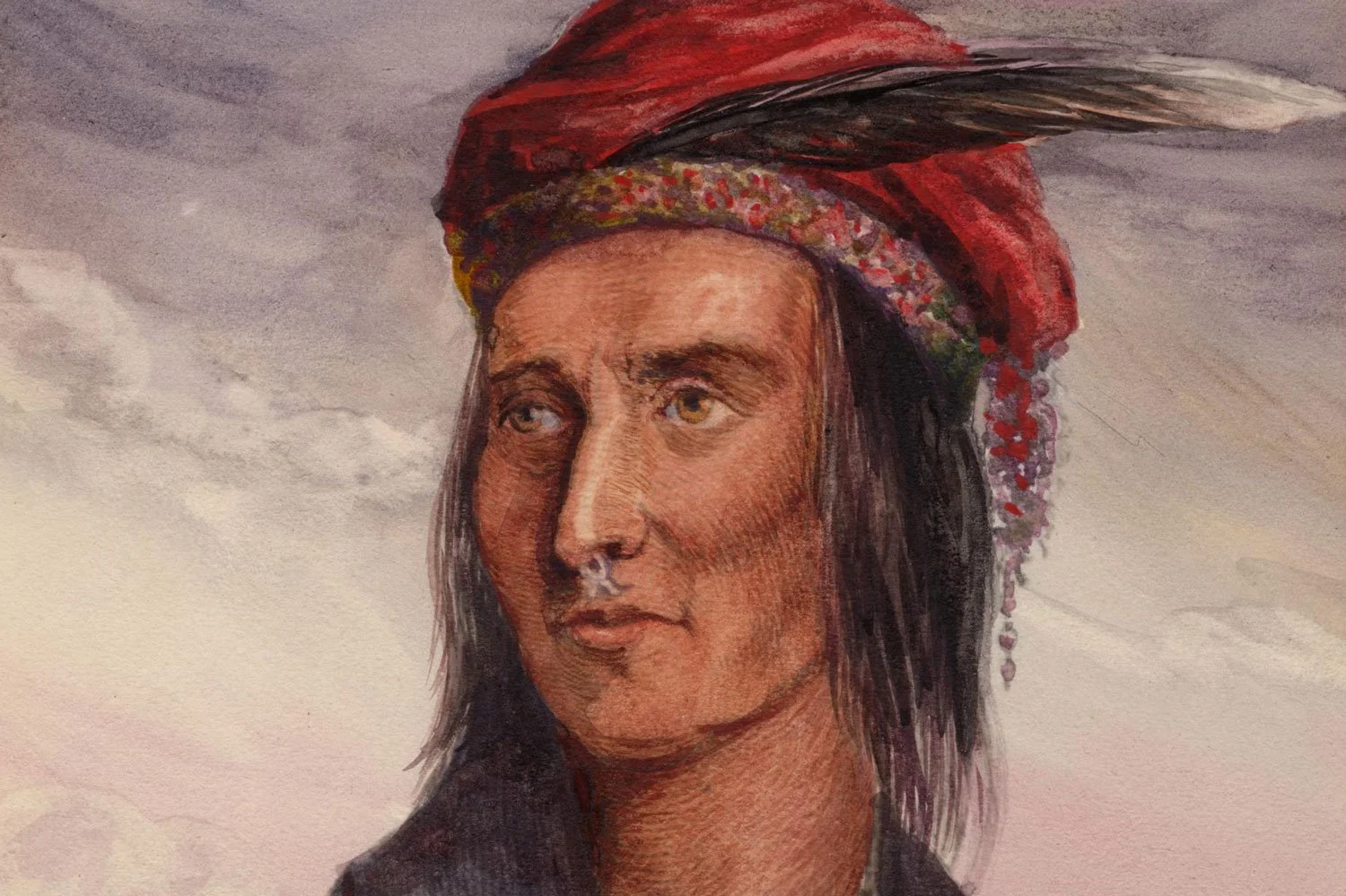

Tecumseh’s War was the last great Indian war in the Northwest Territory and raged from 1811 to 1817. The cause of the conflict was Indian anger at the numerous land cessions made between Indian nations and the United States from 1803 to 1809. While this war overlapped with the War of 1812, the two conflicts were separate events with different goals for the participants.

When James Madison was sworn in as President on March 4, 1809, his most pressing issue was dealing with British and French violations of American neutrality on the high seas. But he also had a rising issue in the west in the form of an Indian confederacy headed by the Shawnee chief Tecumseh and his younger brother, Tenskwatawa, better known to history as the Prophet. The focal point of this movement was the old Northwest Territory, the most fought over area in American history where white settlers and Native Americans vied for control in a virtually continuous conflict that lasted for more than fifty years before coming to an end in 1817.

On March 4, 1789, the Constitutional government, largely the creation of James Madison’s fertile mind, took effect. Naturally, Madison was there at the start to help President George Washington implement and execute this new government. But within a matter of just a few years, Madison would be opposed to the new administration that he helped bring to power as he saw the federal government going in a direction he had not envisioned. Madison’s about face, arguably the greatest political transformation by a national figure in American history, came about largely because of differing ideas regarding what the new government should look like.

In the summer of 1787, leaders from across the United States gathered in Philadelphia for the stated purpose of fixing flaws in the Articles of Confederation. But in the minds of nationalists like James Madison, fixing issues with the Articles was not the answer. What was needed was an entirely new form of government that could allow the fledgling nation to grow. This convention, known at the time as the Philadelphia or Federal Convention, was largely organized by Madison and Alexander Hamilton and the government created at that gathering bore Madison’s indelible stamp.

When James Madison graduated from the College of New Jersey in 1771, he was a man in search of a vocation. Madison had enjoyed studying law but did not want to become a lawyer; he had grown up on a plantation but had no desire to become a farmer and detested the slave culture inherent on a southern plantation. Fortunately, his family’s money and support allowed him time to figure it all out. Ultimately, Madison realized that his true calling was the American cause, and, to that end, James Madison devoted the remainder of his life.

James Madison was one of our nation’s most important Founding Fathers and played a critical role in shaping the United States. Known to history as the Father of the Constitution, Madison was not a dynamic leader of men but was perhaps the most useful subordinate of our Founding Fathers.

When the Democratic-Republicans came to power in the election of 1800, the Jefferson administration effectively shut down and disbanded both the United States Army and Navy. As a result, when American merchant ships were abused and seized as contraband of war on the high seas and in British and French ports during the Napoleonic wars, the United States was helpless to respond.

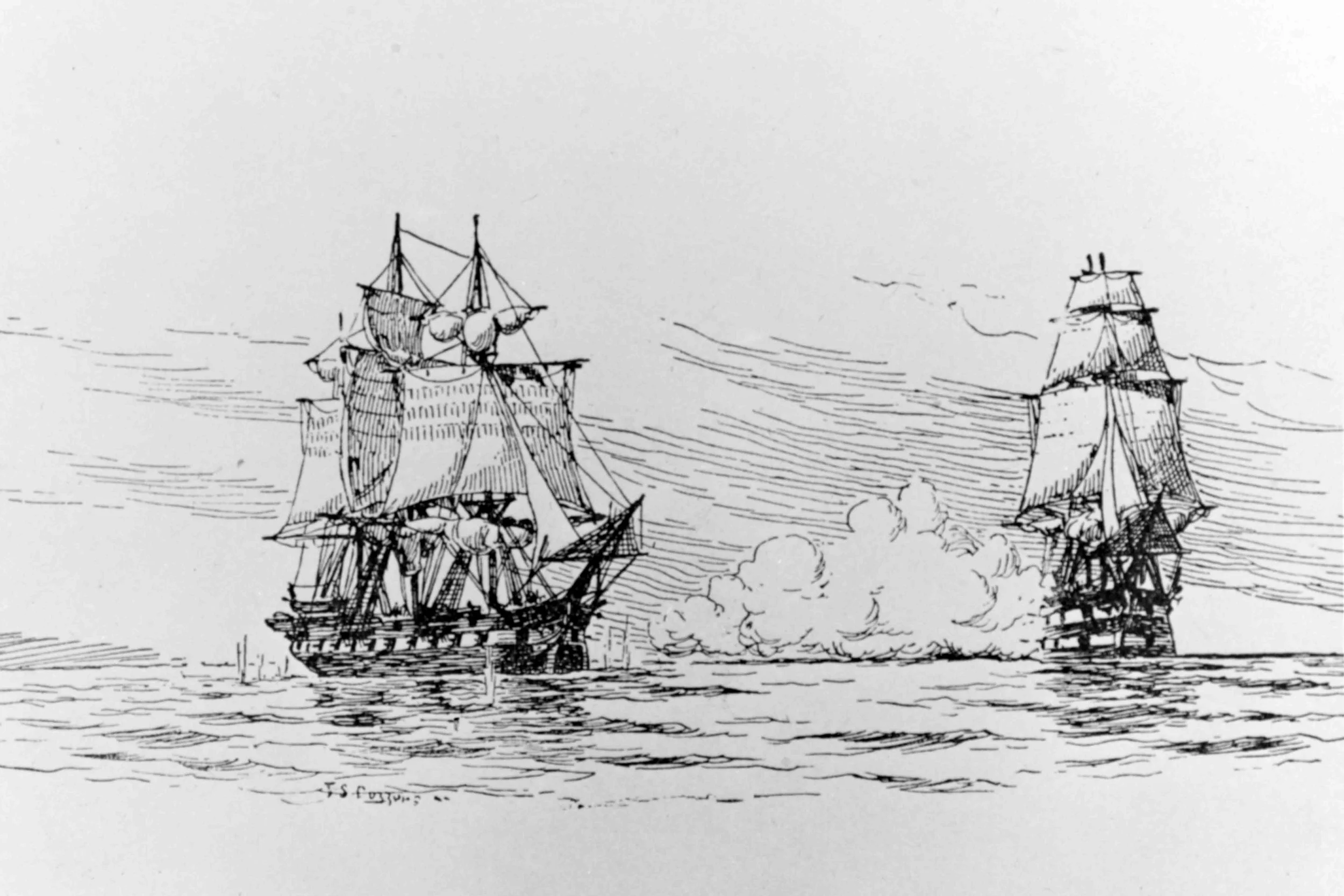

One of the most prominent grievances that led the United States to declare war on Great Britain in 1812 was the impressment of sailors serving on American merchant ships by the Royal Navy. Although this practice continued until after the Napoleonic wars ended in 1815, it truly reached its ugly climax in the summer of 1807 with the infamous Chesapeake-Leopard affair, a naval encounter that brought the two countries to the brink of war.

Many people have called the War of 1812 the “second American Revolution,” and while that phrase has some merit, the facts do not fully support the assertion. It is true that in both cases America’s enemy was Great Britain and the main catalyst that took us to war was American animosity resulting from perceived British wrongs, but the similarities essentially end there.

In early May 1813, Commodore Isaac Chauncey loaded General Henry Dearborn’s army onto his waiting ships and sailed back across Lake Ontario for the second phase of Dearborn’s campaign, the capture of Fort George. Between the men stationed at Fort Niagara and Dearborn’s contingent, the American force consisted of roughly 4,000 men, with command of the army falling to 26-year-old Colonel Winfield Scott, destined to be one of the great military commanders in American history.