The Barbary Wars, Part 5: U.S. Navy Triumphant in Tripoli

After the city of Derne fell to General William Eaton’s expedition on April 27, 1805, Yusef Karamanli, the Pasha of Tripoli, knowing his capital city was next, again sent word to Tobias Lear, the American Consul to Algiers that he wanted peace. The final terms included an exchange of prisoners and the end of all tribute payments to Tripoli, the first agreement of its kind ever reached with a Barbary State. But old habits die hard, and consequently, when America declared war on Great Britain in the summer of 1812 and the United States Navy was occupied with the British, the Barbary States again began to seize American merchant ships.

Tom Hand, creator and publisher of Americana Corner, discusses how the United States took a principled stand that broke the spirit of the Barbary States, and why it still matters today.

Images courtesy of Wikimedia, New York Public Library, Naval History and Heritage Command, National Portrait Gallery - Smithsonian Institution, Library of Congress.

One of the most prominent grievances that led the United States to declare war on Great Britain in 1812 was the impressment of sailors serving on American merchant ships by the Royal Navy. Although this practice continued until after the Napoleonic wars ended in 1815, it truly reached its ugly climax in the summer of 1807 with the infamous Chesapeake-Leopard affair, a naval encounter that brought the two countries to the brink of war.

Many people have called the War of 1812 the “second American Revolution,” and while that phrase has some merit, the facts do not fully support the assertion. It is true that in both cases America’s enemy was Great Britain and the main catalyst that took us to war was American animosity resulting from perceived British wrongs, but the similarities essentially end there.

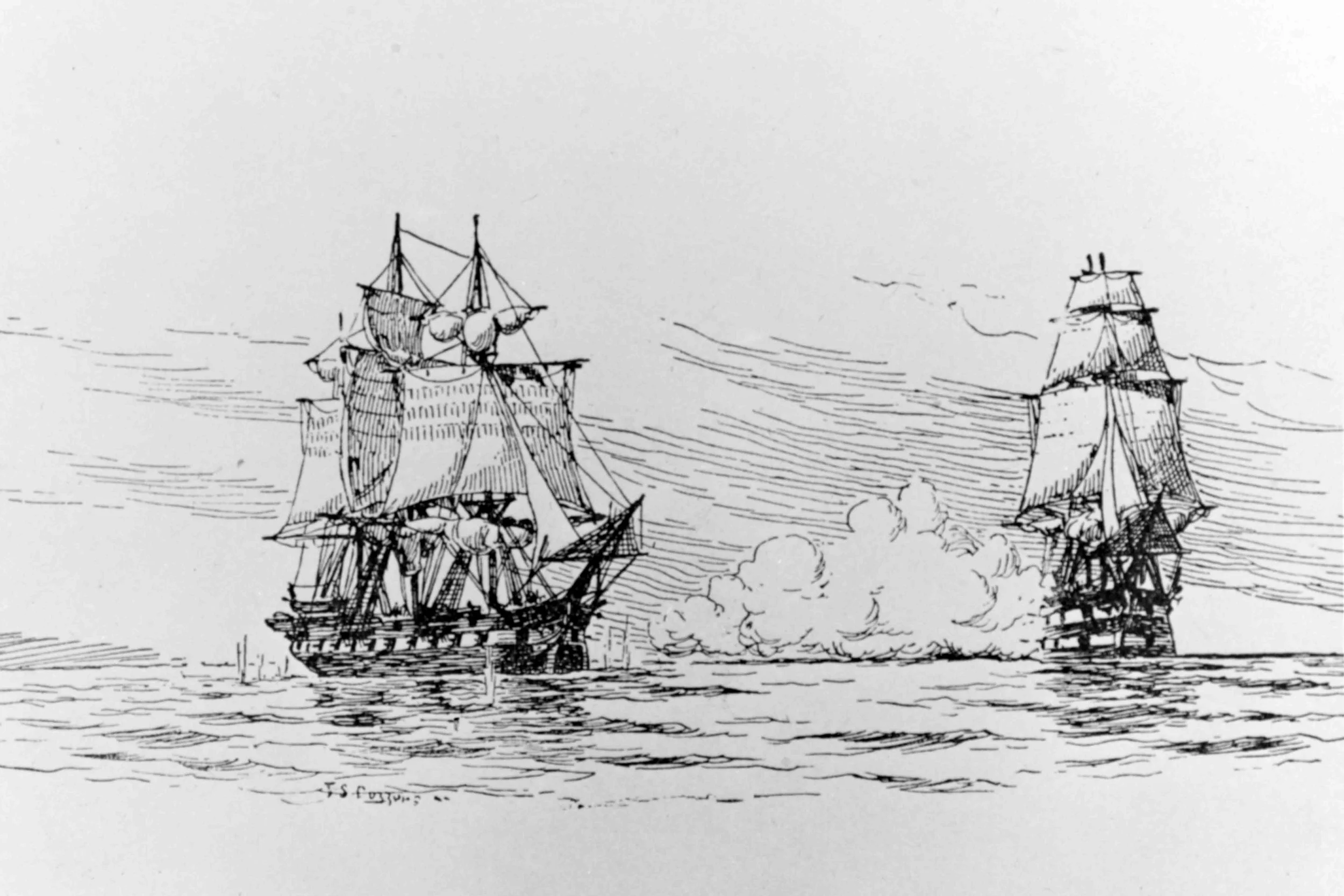

Commodore Edward Preble assembled his considerable American fleet just outside Tripoli harbor in August 1804, determined to punish the city and its corsairs, and force Yusuf Karamanli, the Dey of Tripoli, to sue for peace.

William Eaton led the first successful invasion of a foreign land by the United States when in 1804 he led a handful of Marines and a hodgepodge assembly of Christian mercenaries and unruly Arabs to conquer the Tripolitan port city of Derne.

Captain William Bainbridge managed to run the USS Philadelphia hard aground on a submerged reef in Tripoli harbor on October 31, 1803, and this pristine frigate, one of the top ships in the United States Navy was now in grave danger of falling into the hands of the Tripolitan pirates.

Soon after Thomas Jefferson was sworn in as our country’s third president on March 4, 1801, Yusuf Karamanli, the Pasha of Tripoli, decided to renounce the existing treaty his North African province had with the United States. Unhappy with the amount of his annual tribute and feeling under-compensated compared to his fellow tyrant, the Dey of Algiers, Karamanli demanded that the new President give him a one-time gift of $250,000 and an annual tribute of $20,000.

The Treaty of Paris of 1783 that ended the American Revolution, brought the United States its long-desired liberty and independence from Great Britain. But with that separation came the loss of protection on the high seas for American merchant ships by the Royal Navy. And the removal of that security blanket had painful and expensive consequences for the young country which were first felt several thousand miles away, in the waters of the Mediterranean Sea.

The only fighting in the Quasi-War occurred at sea, and mostly in the Caribbean. But with war at a fever pitch and French interests so close by in Louisiana, there was a very real concern in Congress about a possible French invasion of the United States from the west.

Between 1798 and 1800, the United States fought an undeclared war with France called the Quasi-War, or Half War, because it was not formally recognized by Congress. It was largely a naval conflict fought in the Caribbean and southern coast of America and developed because of a series of related events that soured the formerly strong relationship between the two nations.

America’s first armed conflict with a foreign nation following the American Revolution was not the War of 1812, but rather a mostly forgotten fight called the Quasi-War. Although little known today, in its time it made a significant impact on the course of American history, affecting trade, the creation of the United States Navy, and a presidential election.

When the Democratic-Republicans came to power in the election of 1800, the Jefferson administration effectively shut down and disbanded both the United States Army and Navy. As a result, when American merchant ships were abused and seized as contraband of war on the high seas and in British and French ports during the Napoleonic wars, the United States was helpless to respond.