Heading to Kentucky on the Wilderness Road

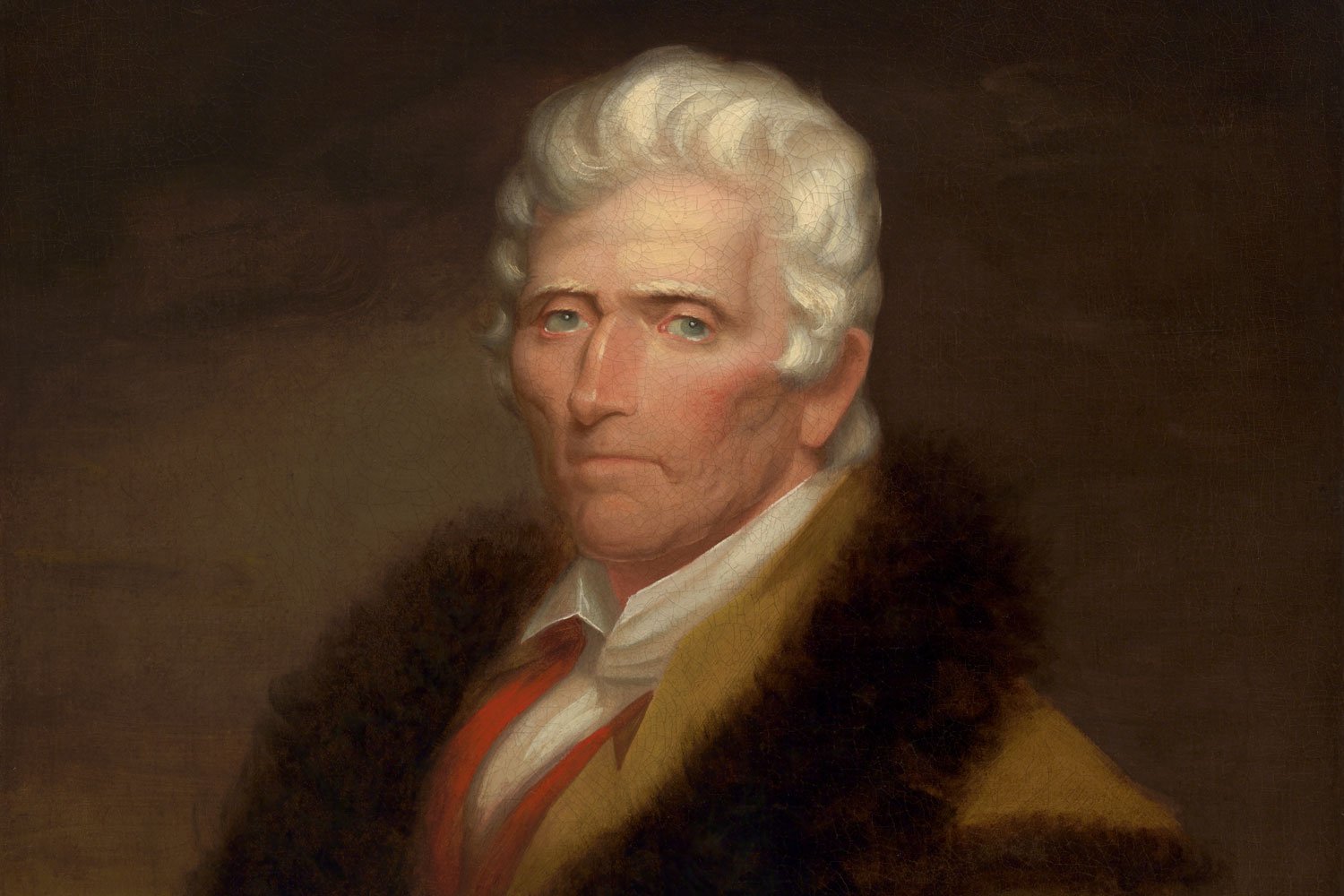

The Wilderness Road, running from northeast Tennessee through the Cumberland Gap, was the main thoroughfare from 1775 to 1820 for Americans heading west into the new promised lands of Kentucky. The pathway, blazed by Daniel Boone, was our nation’s first migration highway, but the trip was not for the faint of heart.

Tom Hand, creator and publisher of Americana Corner, explores how western migration allowed our young nation to expand its boundaries and begin to harvest the region’s incredible riches, and why it still matters today.

Images courtesy of National Park Service, North Carolina State Archives, Library of Congress, Britannica Online, New York Public Library, Yale University Art Gallery, Wikipedia.

The Lewis and Clark Expedition sighted the Pacific Ocean, or more specifically the Columbia River estuary, on November 7, 1805, and spent the next month exploring the area and searching for a suitable location to build a fort for the coming winter. It was a wretched month, one of the worst of the entire journey, as the constant rain soaked the men and their equipment. But despite the conditions, the men felt a growing sense of pride as they considered their incredible accomplishments since leaving St. Louis in May 1804.

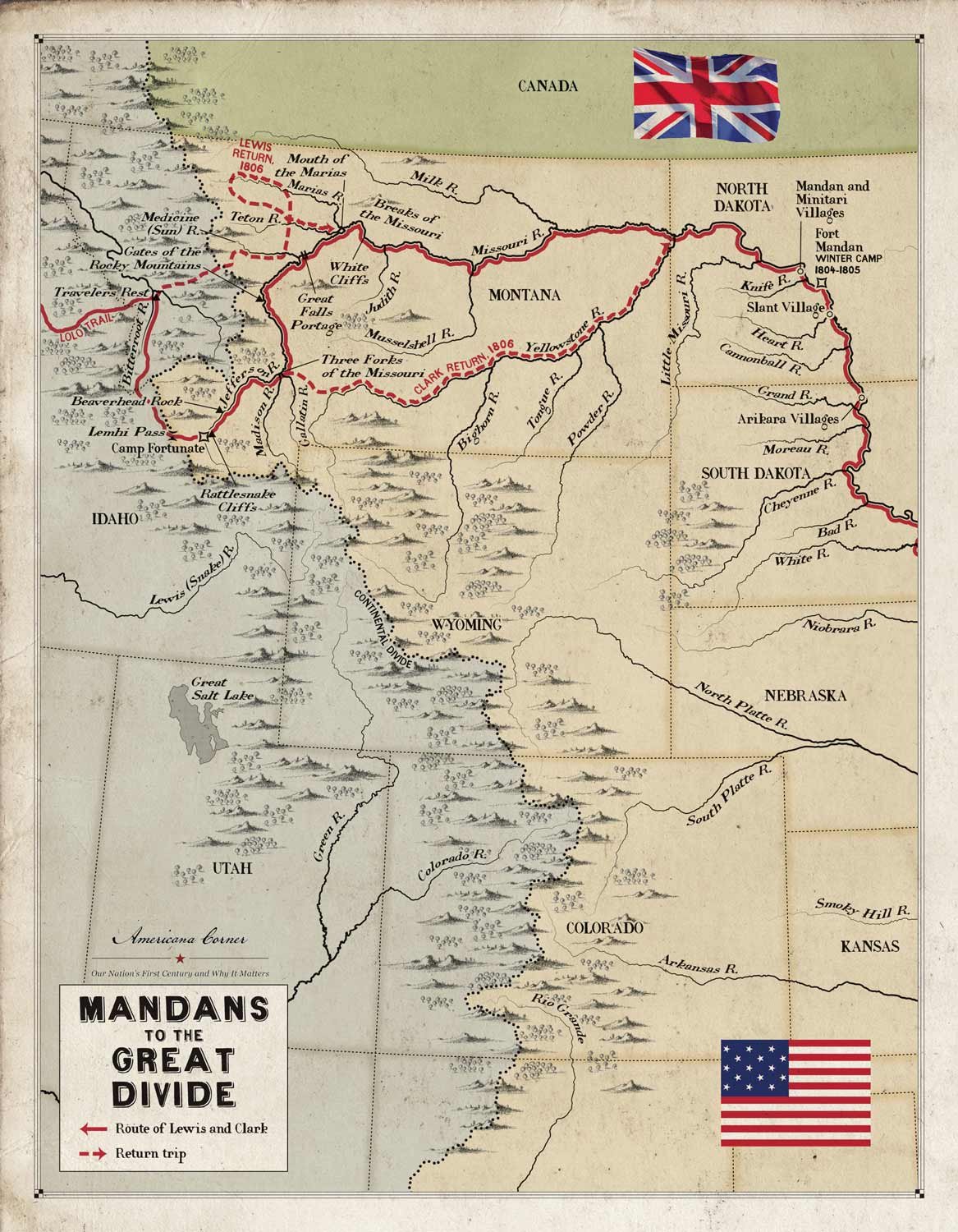

The Lewis and Clark Expedition had been traveling almost straight west and upstream since leaving the Mandan villages in early April 1805. They had safely made it to the west side of the Continental Divide, a great accomplishment, and now would be floating downstream on the western river system that would lead them to the Pacific Ocean.

Upon leaving the Great Falls of the Missouri on July 15, 1805, the Lewis and Clark expedition began to search in earnest for the Shoshone from whom they hoped to purchase horses for their journey over the Rockies. The next day, Lewis identified an abandoned but recent Shoshone camp with a wickiup and signs of numerous horses, but the Indians remained elusive. The captains decided to split up and have Clark take a detachment ahead while Lewis brought up the boats and the rest of the Corps.

As Lewis and Clark continued their journey up the Missouri River in 1805, the Corps was moving further and further from civilization with every stroke of their paddles. Although the Corps had been made aware of the countless wonders to the west through conversations with the Mandans and Hidatsas, it was quite another thing to observe the wonders for themselves, and at seemingly every bend in the river there were new discoveries.

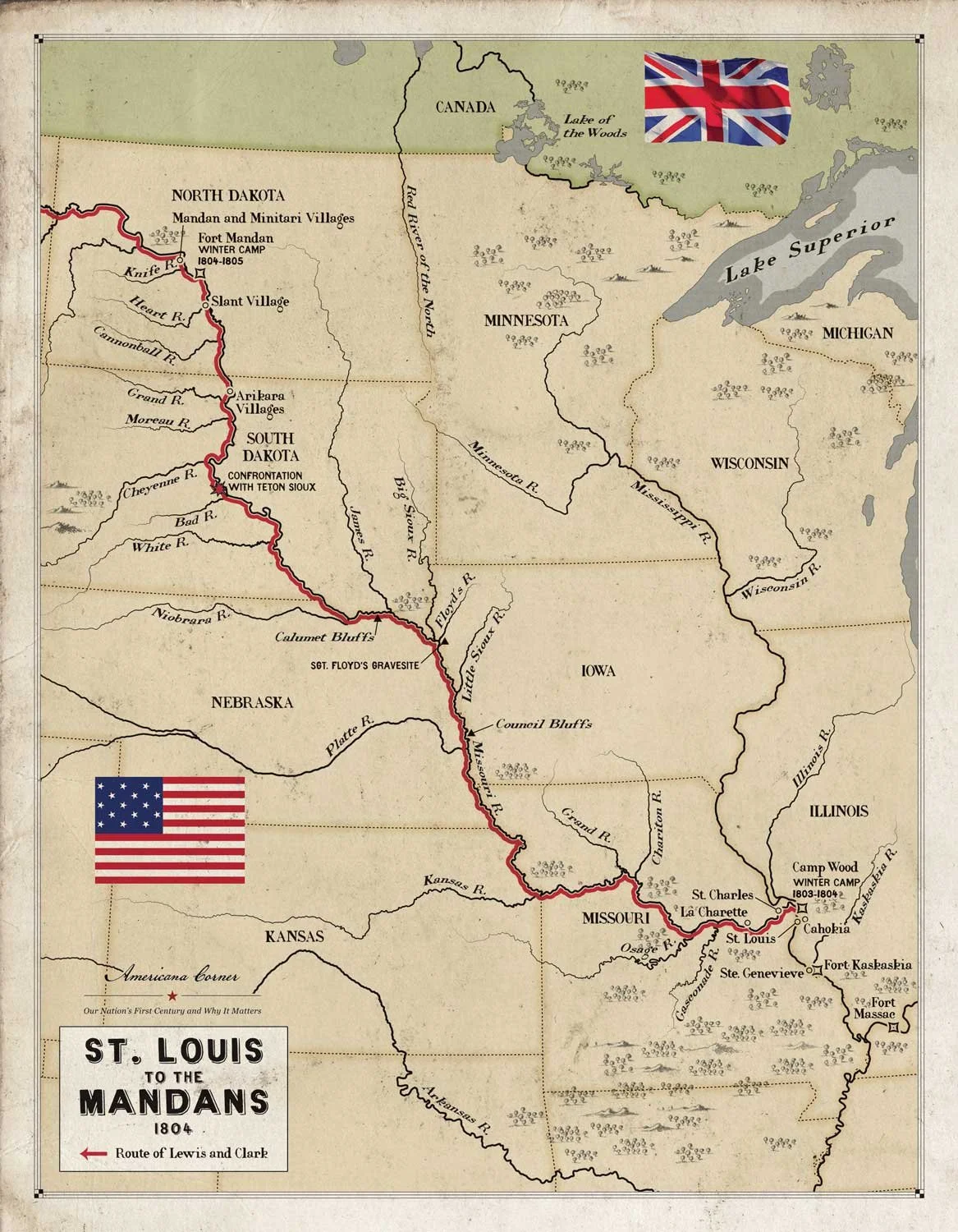

The Corps of Discovery arrived at the Mandan villages near present day Bismarck, North Dakota, in late October 1804 and prepared to settle in for the long winter. For the past five months, the Lewis and Clark expedition had spent most days rowing or pushing their keelboat against the Missouri River’s powerful current, and the men were ready for a break. They were now 1,300 river miles upstream from the nearest civilized settlement and, although they did not know it, they had over 2,000 miles to go to reach the Pacific Ocean.

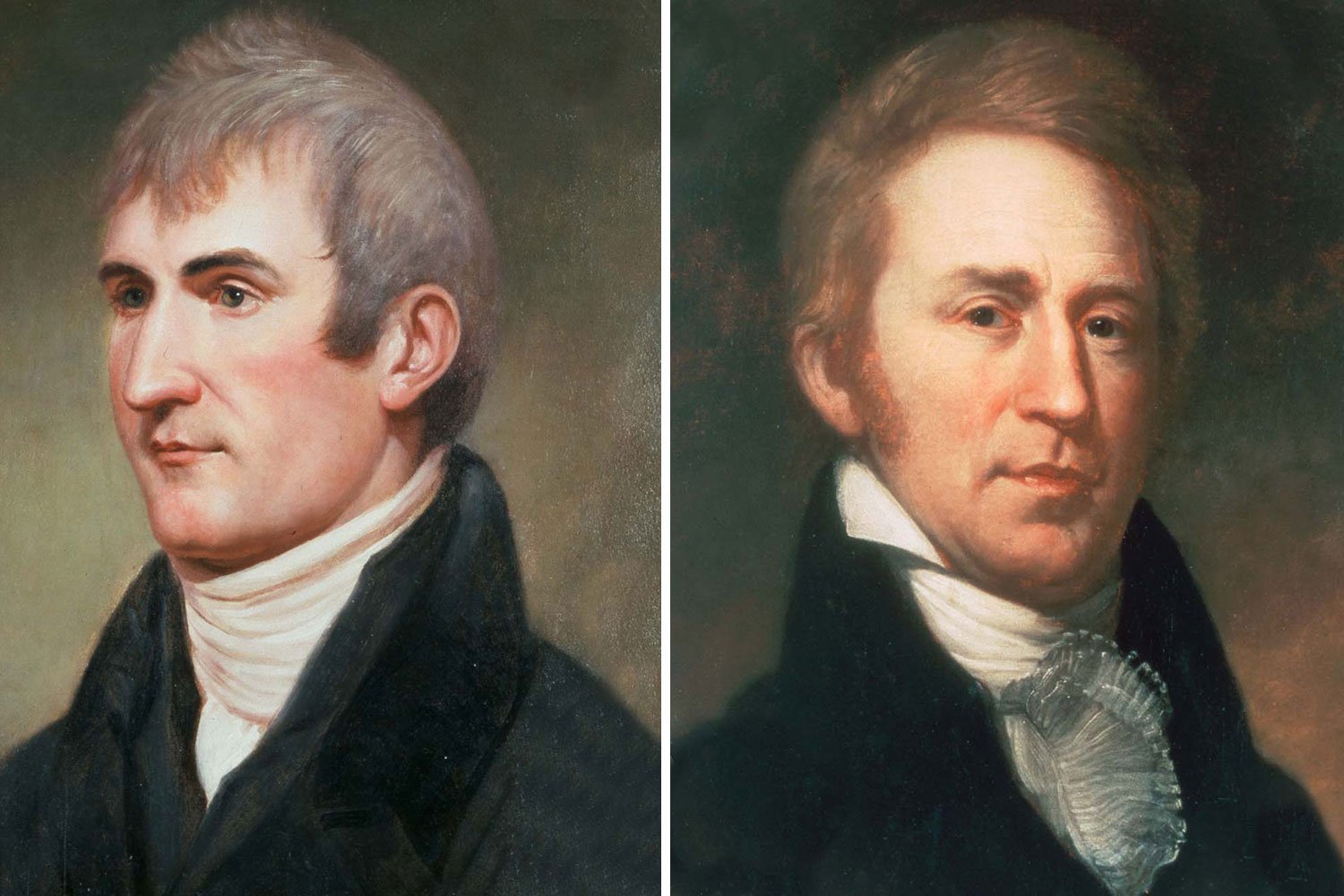

On August 31, 1803, Captain Meriwether Lewis departed from Fort Fayette, today’s Pittsburgh, in the keelboat the Corps of Discovery would take up the Missouri River and, six weeks later, arrived at the Falls of the Ohio and Clarksville, Indiana Territory. It was here, at the town founded by General George Rogers Clark, that Meriwether Lewis and William Clark, the General’s youngest brother, met again for the first time in seven years and commenced the most famous partnership in American history, two men so joined in American lore as to almost be inseparable.

In 1801, Meriwether Lewis was a Captain serving as the paymaster for the First Infantry Regiment of the United States Army. In March, he received a letter from Thomas Jefferson, the newly inaugurated President, asking Lewis to become his private secretary. Lewis, whose family was friends with the Jefferson clan, accepted at once, and thus began a close working relationship, one in which Jefferson became a father figure to Lewis and mentored his young subordinate on policy matters, including his dreams of western exploration and expansion.

By the time they began to assemble the Corps of Discovery in the summer of 1803, Thomas Jefferson and Meriwether Lewis knew more than anyone else about the Louisiana Territory, that immense wilderness the country had recently purchased from France. Although Jefferson had never ventured more than fifty miles west from Monticello, he had dreamed of the trans-Mississippi and studied the region extensively over the previous two decades, even trying unsuccessfully to send exploratory expeditions on several occasions.

The dream of finding an all water route across North America, the mythical Northwest Passage, had been imagined since the time of Christopher Columbus. Incredibly, three hundred years after the Admiral of the Ocean Seas completed his epic voyages, the vast interior of the continent was still essentially unknown to Europeans. This great uncertainty led to numerous theories about what lay beyond what men could see.

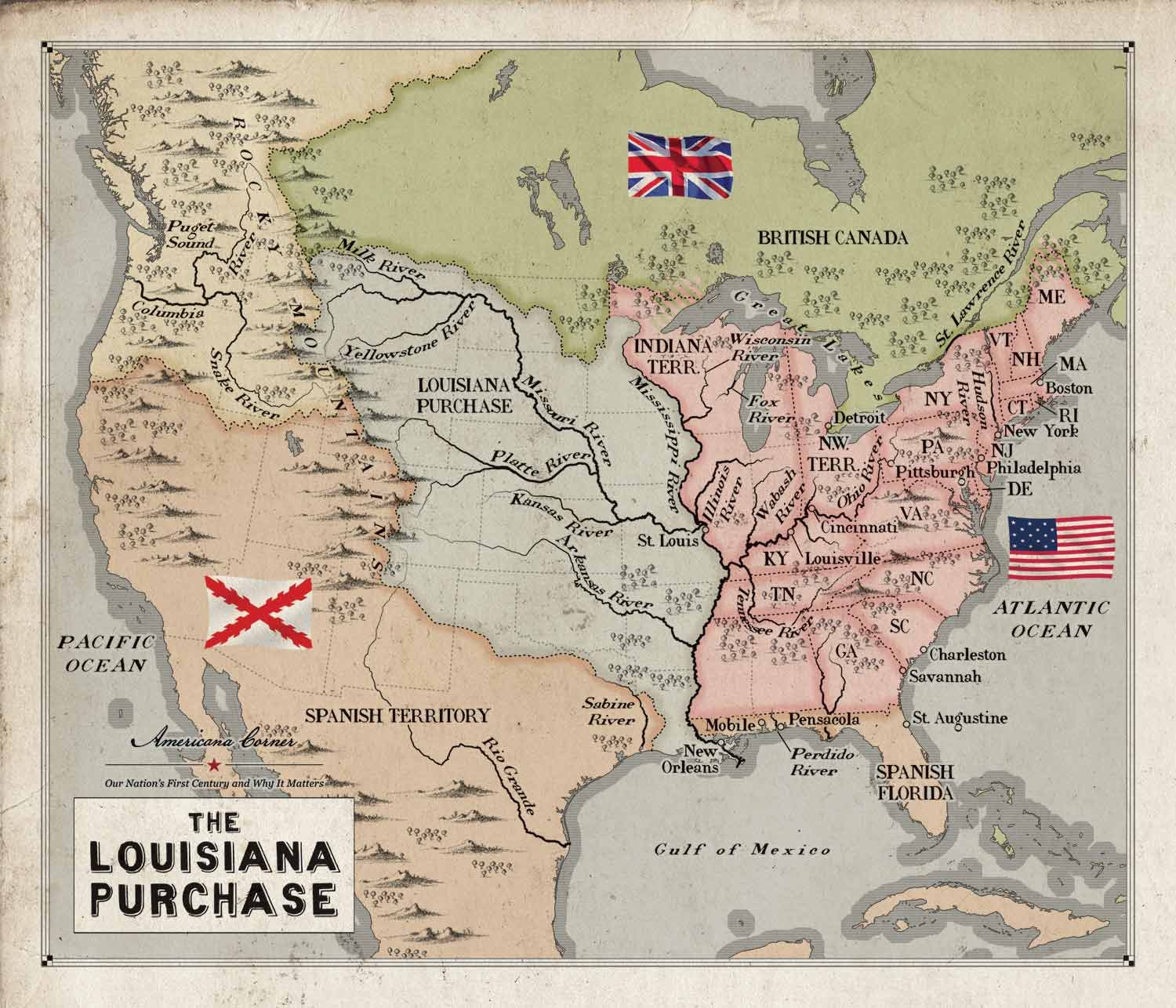

The midnight deal Robert Livingston, United States Minister to France, struck with Francois Barbe-Marbois, Napoleon’s Finance Minister, on April 13, 1803, to purchase the Louisiana territory was one of the most impactful agreements in the history of the United States. It resulted from months of conversations Livingston had had with numerous French officials, creating a foundation for the details that would follow. But as important as this step was, there remained several hurdles to overcome.

As a boy growing up in Virginia, Thomas Jefferson listened to his father tell captivating stories of the pristine wilderness beyond the Appalachian Mountains and dreamed of what opportunities lay in the uncharted lands of North America. As Jefferson grew to manhood, he became a proponent of national expansionism, recognizing that the future greatness of the country lay outside the original thirteen colonies.

The Treaty of Paris of 1783 which officially ended the American Revolution was generous to the United States, much more so than most had expected. Besides recognizing American independence, the provisions which Great Britain proposed greatly expanded the boundaries of the new nation, granting the United States all the land north of the Ohio River as far west as the Mississippi and as far north as British Canada. But like all gifts from adversaries, this one came with some issues that would simmer for decades.

The Louisiana Purchase of 1803 was one of the truly watershed events in American history. The acquisition of this vast land placed the United States firmly on a path towards both the domination of North America and the status of an emerging world power.

By the end of 1765, peace was reached with the tribes who had participated in Pontiac’s rebellion, but all parties recognized this peace was tentative and temporary at best. The British colonist’s insatiable appetite for land and the Indians' need for huge swaths of unsettled wilderness for hunting were two incompatible desires.

Soon after the American Revolution began in 1775, Daniel Boone joined the Virginia militia of Kentucky County (later Fayette County) and was named a captain due to his leadership ability and knowledge of the area. Over the next several years, Boone would participate in numerous engagements.

One of the greatest American explorers from our founding era was Daniel Boone. A legendary woodsman, Boone helped to make America’s dream of westward expansion in the late 1700s a reality.

The Wilderness Road, running from northeast Tennessee through the Cumberland Gap, was the main thoroughfare for Americans heading west into the new promised land of Kentucky from 1775 to about 1820. The pathway, blazed by Daniel Boone, was our nation’s first migration highway, but the trip was not for the faint of heart.

Americans have always had a yearning to move west and discover new lands. Along the way, our ancestors had to overcome many daunting natural barriers, the first of which was the Appalachian Mountains. The Wilderness Road through the Cumberland Gap was our nation’s first pathway through this formidable range.

The Northwest Ordinance of 1787 created the Northwest Territory, officially known as the Territory Northwest of the River Ohio, but also called the Old Northwest. This legislation, enacted by the Congress of the Confederation on July 13, 1787, was our country’s first organized incorporated territory and our initial attempt at expanding the new nation.

Captains Meriwether Lewis and William Clark had guided the Corps of Discovery four thousand miles to the Pacific Ocean, and they planned to continue their explorations on the return leg of their journey. The plan was to temporarily split up the Corps with Clark taking one group to descend and explore the Yellowstone to its junction with the Missouri, Sergeant Ordway leading another party to the Falls of the Missouri and there make preparations to portage the Falls, while Lewis was to lead a third group up the Marias River and determine its northern most latitude to further establish the boundaries of the Louisiana Purchase.